Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases have been considered as the main cause of deaths in the Polish population for many years. However, despite a significant decrease in the rate of mortality due to the diseases of the circulatory system, the total number of deaths has been steadily increasing. In 2018, the total number of deaths in the Polish population was 414,000, which is 3% higher compared to that of the previous year [1].

Currently, cardiological conditions account for about 46% of deaths, whereas in the early 1990s, they accounted for 52%. Prognoses predict that the number of deaths will be greater in the male population, aged 40–64 years, which is the group with the highest rate of mortality due to acute myocardial infarction [2–4]. Sudden cardiac death and acute coronary syndrome (ACS) can possibly lead to death as they result in ischemic heart disease. ACS is clinically manifested as unstable angina (UA), non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), or ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) [5].

ACS is most commonly caused by the formation of atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary arteries. This process progresses rapidly, and it is influenced by coronary risk factors, the correlation between the functions of endothelial and inflammatory cells, and the increased prothrombotic activity of the blood. In most cases, rupture of the atherosclerotic plaques directly results in ACS. Factors that contribute to this process (so-called triggers) include excessive effort, sleep deprivation, stress, excessive consumption of alcohol and drugs, air pollution, and strong emotions connected with natural disasters, warfare, or sport events [6–11].

Soccer is the most popular sport in the world due to several cultural and marketing reasons. Nevertheless, its high unpredictability arouses the greatest emotions among the spectators and supporters. In the literature there are several publications confirming this thesis about the impact of soccer matches on the occurrence of ACS. In the analyses conducted after the semifinal match between France and Holland in the European Soccer Championship in 1996, a 51% increase in the number of admissions was observed among the male population in the Netherlands [12]. A similar relationship was found in the study concerning the World Cup in 1998, in which a 25% increase in the number of admissions for acute myocardial infarctions was observed in England, after England lost to Argentina in a penalty shoot-out [13]. These results are in agreement with those reported by Katz et al. [14, 15] on the 1998 and 2002 World Cups. Wilbert-Lampen et al. [16] indicated a 2.5-fold increase in the incidence of STEMI and a 2.6-fold increase in the incidence of NSTEMI and UA on the days when the German team played during the World Cup held in Germany in 2006. In a study conducted in New Zealand concerning the Rugby World Cup tournaments, it was found that the game lost by the host team was associated with a 50% increase in total admissions for heart failure and a 20% increase in the number of admissions for ACS [17].

In this study, we analyzed the relationship between the matches played by the Jagiellonia Bialystok team (one of the main clubs of the Polish top league) and the number of hospital admissions for ACS. Throughout the last century, Jagiellonia Bialystok has won the Polish Cup and the Super Cup, received medals of the Polish Championship, and participated in European competitions. It is the most successful soccer club in the northeastern part of Poland, which is known for its large group of supporters, who strongly identify themselves with the team.

We aimed to assess the influence of the soccer matches played by the local team on the frequency of admissions for ACS. This study is unique as previous studies have not examined the relationship between hospital admissions for cardiovascular events and local soccer team results. Additionally, a comparative analysis of the effect of soccer matches excludes many variables such as weather conditions and the impact of holidays as factors disturbing the results of games, which have not previously been undertaken.

Material and methods

Hospital admission data

The study was conducted at the Clinical Hospital of Medical University of Bialystok, which was the only center in the city that provided 24-hour services to the patients admitted with interventional cardiology-related conditions throughout the analyzed period. A total of 10 529 patients admitted due to ACS from Bialystok city and county were qualified for analysis.

The demographic and clinical data of the subjects along with the type of ACS were evaluated. The clinical diagnosis of UA, STEMI, and NSTEMI was made by physicians based on the symptoms, the level of the markers of myocardial infarctions, and electrocardiographic imaging.

Data collection

Since 2007, the Jagiellonia Bialystok team has been participating in the top division of the Polish soccer league. All their official matches were included in the analysis. Data were collected from the largest Polish online archive of soccer, 90minut.pl [18], and the official website of Ekstraklasa S.A., the organizer of the Polish top division, ekstraklasa.org [19].

The mean daily meteorological data for Bialystok city and county, including the mean level of relative humidity, temperature, and atmospheric pressure, were obtained from the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management.

Study design

From all of the subjects admitted due to ACS, 6563 males from Bialystok city and county were qualified for further analysis. They were selected based on the study conducted on Polish soccer by PBS Humlard in 2015. It was found that the largest percentage (77.6%) of the team supporters live less than 50 km away from the stadium, in which women constituted only 18.3% [20]. In order to rule out a possible increase in the incidence of cardiovascular events caused by shifts in population within the study area, we included only patients from Bialystok city and county as their officially registered place of residence. Thus, cardiac events were analyzed for local residents only, who may be supporters of the local soccer team, not for visitors from outside the region.

The effect of matches as they are mainly played in the evening hours was analyzed on the day that the match was played and the next day (lag 1). All Jagiellonia Bialystok official matches, including the Championship, Cup, Super Cup, Top League Cup, and European League, were included in the analysis. The variables examined were the match result, audience, number of goals, yellow and red cards, frequency of result change during the match, and penalty shoot-out. Using the additive scale and taking into account the above parameters and the rank of the match (decisive for the championship, relegation, qualification for the championship or relegation group (ESA37), playoffs, or international cups), the analysis identified the matches that could have potentially aroused greater emotions among the spectators.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of variables was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean values with standard deviation, whereas categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages.

A multivariate Poisson regression analysis with a time effect of 0 and +1 day was performed to assess the effect of matches.

To exclude the collinearity effect, each match variable was modelled individually, whereas weather conditions and days with public holidays were added to the model as confounders. To control for short-term trends, we included categorical variables for the day of the week. To exclude the impact of seasonal variations a time-stratified model was used. The time interval for daily data was elapsed calendar month, which resulted in creating 144 strata. The results were presented as the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The threshold of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all the tests.

No observations were found to be missing during the study. All the analyses were performed using the StatSoft Statistica 12 software (StatSoft, 2017, Poland).

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical University of Bialystok (R-1-002/18/2019).

Results

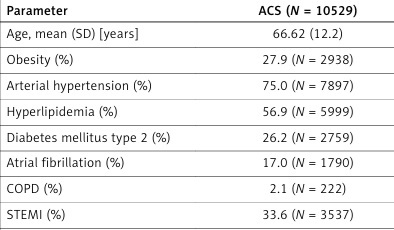

A total of 10 529 patients admitted for ACS between 2007 and 2018, living in Bialystok city and county, met the inclusion criteria of the study. The mean age of the patients was 66.62 ±12.2 years. The majority of the studied population were male (62%, N = 6563). Among the patients, 75.0% (N = 7897) had arterial hypertension, more than one in four was diagnosed with obesity and diabetes, and 98.4% had undergone invasive treatment. The male group was found to be the most burdened with the risk factors for coronary artery disease, such as arterial hypertension and hyperlipidemia (Table I).

Table I

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (N = 10529)

The mean daily number of ACS admissions was 2.40 ±1.7, with the number of admissions in the male population being 1.50 ±1.31. Patients who presented with NSTEMI formed the largest group (37.5%, N = 3947) in the studied population, with male subjects constituting 38.5% (N = 2530), while the patients who presented with STEMI formed 33.6% (N = 3537), in which the male subjects constituted 37.1% (N = 2434). The smallest group in the studied population was that of the patients admitted for UA, forming 28.9% (N = 3045), with male subjects constituting 24.4% (N = 1599) (Table II).

Table II

Frequency of ACS in the study population (N = 10529)

The study analyzed the matches played by the Jagiellonia Bialystok team over 12 consecutive years since 2007. During this period, the team played totally 451 official matches, of which 185 were won, 110 drawn, and 156 lost. Over the last 12 years, the matches played in Bialystok drew a total of 1,727,665 supporters, with an average attendance of 7817 ±4439 (Table III).

Table III

Characteristics of Jagiellonia Białystok soccer matches

Using the additive scale, the matches that potentially aroused greater emotions among the spectators were identified. The comparative analysis of this group of exciting matches (N = 61) showed a higher frequency of admissions due to UA in comparison to other days (1.50 ±1.55 vs. 0.71 ±0.90, p < 0.01). Additionally, winning the match was associated with a significantly lower number of admissions for UA (0.55 ±1.74 vs. 0.74 ±0.93, p = 0.01) (Table IV).

Table IV

Comparative analysis of the frequency of ACS occurrence in the male population depending on the matches played by Jagiellonia Białystok (the next 2 days)

After excluding the impact of seasonal changes and weather conditions, the lost matches played by Jagiellonia Bialystok at home were found to be associated with a 27% increase in the number of male admissions for ACS (RR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.02–1.58, p = 0.03). No delayed effect of soccer matches was observed (Table V).

Table V

Impact of the games on the admissions for ACS in the male population. Data are presented as risk ratios (95% CI)

Discussion

The mean daily number of ACS admissions for ACS was 2.4 ±1.7, which amounted to about 110 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year in the study population. According to the Polish National Health Fund, in the first half of 2017, 681 cases of ACS were reported in the whole of Podlaskie Voivodeship, amounting to over 110 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. These numbers are smaller than those recorded in the other regions of Poland. For instance, in the Mazovian Voivodeship, the number of cases was twice as high, while in Silesia it was four times higher [21]. In the Polish AMI-PL register, the number of admissions for ACS was 176 per 100,000 inhabitants, with a decreasing trend observed over the years, which is in line with the results of our study [22]. Similar findings were observed when the rate of cardiovascular mortality was analyzed. In 2012, the highest mortality rate was recorded in the Silesian, Swietokrzyskie, and Lublin Voivodeships (over 490 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants), which was about 25% higher than in the Podlaskie Voivodeship, where the lowest rate of mortality was recorded (394 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants) [23].

ACS is most commonly caused by the sudden rupture of atherosclerotic plaques. One of the factors that trigger this process may be the emotions related to sports. While watching sport events, there occurs increased activation of the sympathetic system, inhibition of the activity of vagus nerves, and activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis with increased secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone, cortisol, and testosterone. These changes lead to an increase in blood pressure, heart rate, and myocardial contractility, and consequently, to increased myocardial consumption of oxygen with a decreased distribution. In addition, the decreased fibrinolytic activity and increased ability to activate blood platelets play an important role. All the mentioned processes may lead to the rupture of atherosclerotic plaques and ultimately ACS [24, 25].

The lost matches played by Jagiellonia Bialystok at home were found to be associated with a 27% increase in the number of male admissions for ACS. Several studies related to national teams also confirm this statement [12–17]. Our study is the first to evaluate the impact of single team results on the frequency of ACS. Only one previous analysis, by Kirkup et al. [26], has focused on a local team. The lost home matches played at the highest level in England were associated with a 28% increase in the mortality rate due to ACS and stroke.

Similar analyses about local teams were performed not for soccer but for other sport disciplines. The analysis of the final American Football matches played by the team from Los Angeles showed that after a lost game of hosts, there was a 17% increase in the rate of mortality due to acute myocardial infarction. By contrast, winning the Super Bowl was associated with a 6% decrease in the number of deaths, in comparison to the control days, in the county of Los Angeles [27]. Some single studies analyzing the influence of individual sports are also available. In a study on sumo wrestling, the national Japanese sport, a 9% increase in the occurrence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests was noted on the tournament day, and in the case of patients aged over 75 years, there was a 13% increase compared to the control days [28].

These findings show that emotions are not only related to soccer but also related to other sports and these are often correlated with the results of a team. Our study also attempted to assess whether the drama of the games played by the Jagiellonia Bialystok team affected the number of admissions for ACS. A comparative analysis of the matches associated with increased emotions showed a 20% higher incidence of ACS compared to other match days, but a statistical significance was indicated only in the male subgroup hospitalized due to UA. Thus, we believe that not only the final result but also the drama of the game is important. Apart from the mechanisms mentioned above, the pathogenesis of the relationship between the sport events and the admissions for ACS includes increased smoking and increased consumption of alcohol that accompany sport emotions [29].

It is worth mentioning that some studies also present contrasting findings. Barone-Adesi et al. [30] noted no increase in the number of admissions due to ACS on the days of soccer matches involving the Italian national team. The same observation was made in the study on the Portuguese national team [31]. In several smaller studies on the German population, no impact of soccer matches on the frequency of cardiovascular and cerebral incidents was identified [32, 33].

Our study provides further evidence of the role of triggering factors, including emotions, in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular incidents in the male population. Therefore, education about the influence of stressors on the occurrence of ACS should be as important as reducing the classical risk factors.

One of the most significant limitations of the study is its retrospective character. Despite the fact that the group of potential supporters of Jagiellonia Bialystok was selected on the basis of sociological research, the lack of an interview in this direction is the main limitation of the study. We believe that this did not affect the results, because the observation time of more than 10 years and the large group of patients covered by the study seem to compensate for these shortcomings. Nevertheless, further studies on the influence of sport games on the occurrence of cardiac events should have prospective character.

In conclusion, the results achieved by the local professional soccer team are related to the incidence of ACS in the male population. Emotions related to lost games play an important role as a triggering factor for ACS in the male population.