Introduction

Polypharmacy is commonly defined as the simultaneous use of five or more drugs [1]. But other definitions has been proposed: some authors propose a more detailed breakdown of the cut-off (“5 to 7” and “8 and over”), allowing for the identification of those with an increased risk [2]; Steinman et al. [3] proposes a threshold of 8 medications justified by the fact that below this number, the risk of under-use is greater than the risk of polypharmacy or inappropriate prescription; and others consider polypharmacy as the use of inappropriate, ineffective or duplicate medication [4].

Polypharmacy is estimated to affect 30–70% of older adults [5], and it has been associated with an increased risk of falls [6], inappropriate prescriptions, reduced patient adherence, drug interactions, hospital admissions [7] and mortality [8]. It is estimated that at least 75% of these adverse events are potentially preventable [9]. In some cases, an adverse drug reaction can be misinterpreted as a new medical condition and a new drug is prescribed, placing the patient at a higher risk of developing additional adverse drug reactions; this problem is known as the “prescribing cascade” [10].

According to Charlesworth et al. [11] the increased number of prescription medications seen in older adults in the USA between 1988 and 2010 was driven, in part, by higher use of cardioprotective medications (statins, anti-hypertensives, and antidiabetics). Still the use of antidepressants, as well as the use of medication from other classes and subclasses (proton-pump inhibitors, thyroid hormones, bisphosphonate, among others), also increased.

In Portugal there are a few studies about the prevalence of polypharmacy in some of its regions, none on a national scale. A 2016 study in a primary care health centre in the north of Portugal identified a prevalence of polypharmacy of 59.2%, higher in women (62%) than in men (54.8%) [12]. In the Portuguese public health system the patients can only go to secondary care through referral from primary care, but once in both levels of care both doctors can prescribe and renew all the patient’s medications. The medications’ prescription occurs through the mandatory nationwide electronic prescription platform (PEM).

The aim of this study was to identify the nationwide prevalence of polypharmacy in older adults in Portugal and its sociodemographic and clinical profiles. Although polypharmacy can be linked to drug-drug interactions (both pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics) and to adverse drug reactions, these results were presented in a previous paper [13]. Moreover, given the lack of consensus for the definition of polypharmacy and since multimorbidity and the use of multiple medications is common in older adults [14] we also intended to use a new definition of polypharmacy (equal to or greater than the median number of drugs taken by the population) and compare it to the most commonly used.

Material and methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study whose details, definitions and methods were previously published [15].

The study was conducted in agreement with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Beira Interior and Portuguese Healthcare Administrative Regions. The reporting of this study conforms to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.

Participants

Since there were 2.18 million older adults (≥ 65 years) in Portugal and the literature suggests that the range of polypharmacy is between 30% and 70%, we assumed the rate to be over 50% because of epidemiological concern for better evidence and larger sampling. We estimated a sample of a minimum 742 patients for a 95% CI and a maximum precision error of 5%. In agreement with the geographical distribution of the population of Portuguese aged 65 and older across the five mainland healthcare administrative regions and two autonomous regions (Madeira and Azores), noted in PORDATA [16], a random sample of 757 patients was provided by the information department of the ministry of health, SPMS (Serviços Partilhados do Ministério da Saúde), and invited family doctors from autonomous regions, due to lack of digital databases within these regions.

Data collection procedures

Data collection occurred in March 2018 (data extracted on March 30th). In brief, the SPMS provided us with an electronic file with the variables of the study from the randomly selected (by patient’s national health number) sample of the five healthcare administrative regions. This electronic file contained anonymised information stored in the patient’s electronic medical records. Since SPMS does not have access to electronic medical records from patients in the two autonomous regions, we invited two medical doctors, one from each autonomous region, to provide us with the needed information. The patients selected met the inclusion criteria and also had had an appointment in six pre-randomized days of the month. We studied the prescribed medications using the mandatory nationwide PEM [17]. There is an unknown number of over-the-counter medications consumed by the Portuguese population and as they can be bought without prescription, there is no way to access this information. SPMS could not provide us with information regarding level of education, since in most cases it was missing from the medical records.

Outcome variable

For each patient, polypharmacy was measured either by the simultaneous taking of ≥ 5 drugs or by the median number of drugs at the time of data collection. The rationale for such a study resides in the lack of consensus regarding definition of polypharmacy [18]; also because of multimorbidity older patients are consuming an increasing number of medications [19]. There is a study [2] that proposes a threshold of 8 medications, justified by the fact that below this number, there is a big risk of under-use. Prescribed medication (from April 2017 to March 2018) was encoded following the Portuguese pharmacotherapeutic classification using the most discriminative level possible. The Portuguese pharmacotherapeutic classification has similarities with the ATC (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical) classification and was adapted by INFARMED (National Authority of Medicines and Health Problems) [20]. We defined chronic medication as medication prescribed for more than 3 months.

Independent variables

These were sociodemographic characteristics such as age, gender (male/female), area of residence (in terms of health administrative region) and clinical profile (chronic health problems according to International Classification of Primary Care, second edition – ICPC-2).

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained from Institutional Ethics Committee at the University of Beira Interior and Portuguese Healthcare Administrative Regions.

Statistical analysis

In addition to the descriptive analysis, we also performed the χ2 test for nominal qualitative characteristics. Lastly, we performed a logistic regression with all the statistically significant variables. All tests were two-sided using a significance level of 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS V.24.0.

Results

Characteristics of participants

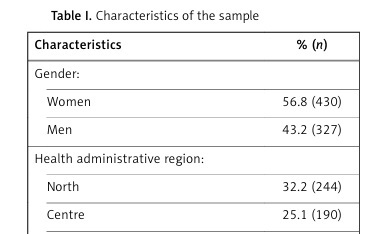

The sample consisted of 757 people, mean age was 75.5 ±7.9 years (75.1 ±7.9 years for men and 75.8 ±7.8 years for women) and median number of drugs was 8. Table I shows the characteristics of the sample.

Table I

Characteristics of the sample

[i] A – general and unspecified, B – blood, blood forming organs, lymphatics, spleen, D – digestive, F – eye, H – ear, K – circulatory, L – musculoskeletal, N – neurological, P – psychological, R – respiratory, S – skin, T – endocrine, metabolic and nutritional, U – urology, X – female genital system and breast, Y – male genital system, Z – social problems, 2 – central nervous system, 3 – cardiovascular system, 4 – blood, 5 – respiratory system, 6 – digestive system, 7 – genitourinary system, 8 – hormones and medications used to treat endocrine diseases, 9 – locomotive system, 10 – antiallergic medication, 16 – antineoplastic and immunomodulatory drugs.

Prevalence of polypharmacy

More than 9 out of 10 older patients (93.4%) were on at least 1 medication, with an overall average of 8.2 (95% CI: 7.9–8.6), 7.5 (95% CI: 7–8) in men and 8.8 (95% CI: 8.3–9.3) in women.

The rate of polypharmacy, use of 5 or more drugs simultaneously, was 77% (95% CI: 74–80%). With a cut-off of equal to or more than the median number of drugs (equal to 8), an important percentage of polypharmacy 55% (95% CI: 51–58%) remained present.

According to Table II there was a significant relationship between health administrative region, age, number of chronic health problems and number of prescribers and both definitions for polypharmacy (≥ 5 drugs and ≥ median number of drugs). Gender was only significant in our new definition of polypharmacy.

Table II

Prevalence of polypharmacy according to characteristics

| Characteristics | Older adults without polypharmacy % (n) | Percentage of older adults with polypharmacy (95% CI) | Mean number of drugs (95% CI) [median] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 5 drugs | P-value (χ2 test) | ≥ 8 drugs | P-value (χ2 test) | |||

| Gender: | 0.059 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Women | 20.5 (88) | 79.5 (342) | 60.5 (260) | 8.78 (8.30–9.25) [8] | ||

| Men | 26.3 (86) | 73.7 (342) | 47.4 (155) | 7.47 (6.98–7.96) [7] | ||

| Health administrative region: | 0.022 | 0.017 | ||||

| North | 26.6 (65) | 73.4 (179) | 49.6 (121) | 7.77 (7.18–8.36) [7] | ||

| Centre | 17.9 (34) | 82.1 (156) | 58.9 (112) | 8.62 (7.96–9.28) [8] | ||

| Lisbon-Tejo Valley | 20.0 (42) | 80.0 (168) | 59.5 (125) | 8.69 (8.02–9.36) [8] | ||

| Alentejo | 27.3 (18) | 72.7 (48) | 53.0 (35) | 7.48 (6.33–8.64) [8] | ||

| Algarve | 41.2 (14) | 58.8 (20) | 41.2 (14) | 6.29 (4.49–8.10) [6] | ||

| Madeira | 14.3 (1) | 85.7 (6) | 28.6 (2) | 9.43 (5.13–13.73) [6] | ||

| Azores | 0 (0) | 100 (6) | 100 (6) | 14.17 (9.50–18.83) [13] | ||

| Age [years]: | < 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| < 75 | 28.2 (110) | 71.8 (280) | 49.2 (192) | 7.73 (7.25–8.22) [7] | ||

| ≥ 75 | 17.4 (64) | 82.6 (303) | 60.8 (223) | 8.72 (8.24–9.21) [9] | ||

| Number of chronic health problems | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| 0-2 | 48.1 (63) | 51.9 (68) | 35.9 (47) | 5.44 (4.67–6.21) [5] | ||

| 3-4 | 35.6 (52) | 64.4 (94) | 41.1 (60) | 6.97 (6.17–7.78) [6] | ||

| 5-6 | 23.3 (31) | 76.7 (102) | 48.1 (64) | 7.80 (7.06–8.55) [7] | ||

| 7-8 | 12.6 (16) | 87.4 (111) | 63.8 (81) | 9.22 (8.50–9.94) [9] | ||

| 9-10 | 7.8 (7) | 92.2 (83) | 64.4 (58) | 9.21 (8.36–10.06) [9] | ||

| ≥ 11 | 3.8 (5) | 96.2 (125) | 80.8 (105) | 11.15 (10.34–11.95) [10] | ||

| Chronic health problems (ICPC2): | ||||||

| A | 10.6 (9) | 89.4 (76) | 0.004 | 62.4 (53) | 0.139 | 9.40 (8.42–10.38) [9] |

| B | 15.8 (9) | 84.2 (48) | 0.179 | 66.7 (38) | 0.062 | 9.25 (7.98–10.52) [9] |

| D | 13.0 (36) | 87.0 (240) | < 0.001 | 60.1 (166) | 0.026 | 8.93 (8.38–9.49) [8,5] |

| F | 17.4 (27) | 82.6 (128) | 0.065 | 63.9 (99) | 0.011 | 9.25 (8.43–10.08) [9] |

| H | 12.6 (11) | 87.4 (76) | 0.015 | 63.2 (55) | 0.094 | 9.70 (8.58–10.82) [9] |

| K | 16.9 (99) | 83.1 (488) | < 0.001 | 61.2 (359) | < 0.001 | 8.98 (8.60–9.37) [9] |

| L | 17.6 (69) | 82.4 (323) | < 0.001 | 62.0 (243) | < 0.001 | 8.95 (8.49–9.42) [8] |

| N | 16.0 (19) | 84.0 (100) | 0.047 | 67.2 (80) | 0.003 | 10.06 (9.13–10.99) [10] |

| P | 16.5 (43) | 83.5 (217) | 0.002 | 60.4 (157) | 0.026 | 9.01 (8.43–9.59) [8] |

| R | 10.7 (19) | 89.3 (158) | < 0.001 | 67.2 (119) | < 0.001 | 9.72 (9.03–10.41) [9] |

| S | 19.2 (28) | 80.8 (118) | 0.224 | 56.2 (82) | 0.717 | 8.66 (7.87–9.44) [8] |

| T | 17.3 (90) | 82.7 (429) | < 0.001 | 60.5 (314) | < 0.001 | 8.97 (8.56–9.38) [9] |

| U | 16.0 (26) | 84.0 (137) | 0.016 | 65.0 (106) | 0.003 | 9.09 (8.35–9.83) [9] |

| X* | 10.9 (7) | 89.1 (57) | 0.041 | 67.2 (43) | 0.233 | 9.72 (8.45–10.99) [10] |

| Y** | 19.1 (22) | 80.9 (93) | 0.030 | 58.3 (67) | 0.004 | 8.63 (7.78–9.47) [8] |

| Z | 18.5 (5) | 81.5 (22) | 0.574 | 63.0 (17) | 0.387 | 9.44 (7.65–11.24) [10] |

| Pharmacological classes (INFARMED): | ||||||

| 2 | 9.2 (52) | 90.8 (512) | < 0.001 | 68.8 (388) | < 0.001 | 9.77 (9.42–10.12) [9] |

| 3 | 11.8 (73) | 88.2 (546) | < 0.001 | 63.8 (395) | < 0.001 | 9.35 (9.01–9.69) [9] |

| 4 | 2.5 (7) | 97.5 (272) | < 0.001 | 83.5 (233) | < 0.001 | 11.27 (10.78–11.75) [11] |

| 5 | 7.5 (12) | 92.5 (148) | < 0.001 | 78.1 (125) | < 0.001 | 11.14 (10.42–11.85) [11] |

| 6 | 5.7 (22) | 94.3 (361) | < 0.001 | 78.1 (299) | < 0.001 | 10.81 (10.37–11.24) [10] |

| 7 | 13.6 (17) | 86.4 (108) | 0.006 | 63.2 (79) | 0.039 | 9.49 (8.68–10.30) [9] |

| 8 | 8.4 (27) | 91.6 (295) | < 0.001 | 74.2 (239) | < 0.001 | 10.64 (10.14–11.14) [10] |

| 9 | 8.6 (35) | 91.4 (373) | < 0.001 | 74.3 (303) | < 0.001 | 10.11 (9.69–10.53) [10] |

| 10 | 5.2 (8) | 94.8 (146) | < 0.001 | 79.9 (123) | < 0.001 | 11.07 (10.39–11.76) [11] |

| 16 | 0 (0) | 100 (12) | 0.056 | 91.7 (11) | 0.010 | 13.58 (9.80–17.37) [13.5] |

| Number of prescribers: | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 34.5 (167) | 65.5 (317) | 39.5 (191) | 6.48 (6.10–6.86) [6] | ||

| > 2 | 2.6 (7) | 97.4 (266) | 82.1 (224) | 11.29 (10.78–11.80) [11] | ||

A – general and unspecified, B – blood, blood forming organs, lymphatics, spleen, D – digestive, F – eye, H – ear, K – circulatory, L – musculoskeletal, N – neurological, P – psychological, R – respiratory, S – skin, T – endocrine, metabolic and nutritional, U – urology, X – female genital system and breast, Y – male genital system, Z – social problems, 2 – central nervous system, 3 – cardiovascular system, 4 – blood, 5 – respiratory system, 6 – digestive system, 7 – genitourinary system, 8 – hormones and medications used to treat endocrine diseases, 9 – locomotive system, 10 – antiallergic medication, 16 – antineoplastic and immunomodulatory drugs.

After adjustments, Table III shows that the likelihood of having polypharmacy (as ≥ 5 drugs) increased significantly with age (OR = 1.05 (1.02–1.08)), number of chronic health problems (OR = 1.24 (1.07–1.45)) and number of prescribers (OR = 4.71 (3.42–6.48)).

Table III

Logistic regression model for polypharmacy

[i] OR – odds ratio, A – general and unspecified, D – digestive, F – eye, H – ear, K – circulatory, L – musculoskeletal, N – neurological, P – psychological, R – respiratory, S – skin, T – endocrine, metabolic and nutritional, U – urology, X – female genital system and breast, Y – male genital system.

The likelihood of having polypharmacy with our new definition (as ≥ median of drugs taken by the sample) increased significantly in females (OR = 1.86 (1.24–2.80)), with number of chronic health problems (OR = 1.11 (1.02–1.20)) and number of prescribers (OR = 2.32 (1.97–2.73)).

Pharmacological subclasses and patterns of polypharmacy

Table III shows the odds ratio measured impact of having each specific chronic health problem (according to ICPC2). For patients suffering from chronic health problems related to the cardiovascular system there were 3.8 times and 2.4 times greater probability of having polypharmacy (as ≥ 5 drugs and ≥ median number of drugs taken, respectively) compared to those not suffering from health problems related to that specific system.

Table IV shows the most used pharmacological subclasses in this random sample. Three pharmacological subclasses were present in more than half of the sample: ACE inhibitor/ARBs (56.8%), statins (52%) and analgesics and antipyretics (50.6%).

Table IV

Fifteen most used pharmacological subclasses and common chronic health problems

Comparation between both definitions of polypharmacy in detecting potentially inappropriate medication

The common definition (≥ 5 drugs taken) had a sensitivity of 91.3%, specificity of 54.2%, positive predictive value of 81.3% and negative predictive value of 74.1%.

Our definition (≥ median number of drugs taken) had a sensitivity of 72.6%, specificity of 84.0%, positive predictive value of 90.8% and negative predictive value of 58.5%.

The mean number of PIM in older adults with polypharmacy according to the common definition was 2.19 (95% CI: 2.03–2.34) compared to 0.34 (95% CI: 0.24–0.44) in those without polypharmacy. According to our definition (≥ median number of drugs taken) we found a prevalence of 2.64 PIMs (95% CI: 2.46–2.83) in those with polypharmacy compared to 0.69 PIMs (95% CI: 0.58–0.80).

Discussion

As described in the project protocol [15], the objectives for its phase I were to identify the prevalence and its characteristics of polypharmacy and PIMs in the elderly Portuguese population. The results related to the PIMs have already been published [13], but they are not necessarily related to the polypharmacy.

Strengths of the study

This was the first study to report the prevalence and patterns of polypharmacy in older adults attending primary care consultations on a national scale in Portugal.

We performed a cross-sectional study, which is the most frequent design to assess prevalence and its characteristics.

We used the most discriminative chemical subgroup of the Portuguese pharmacotherapeutic classification, to assess polypharmacy; this can minimize the bias of medical changes.

We assessed the number of medications taken by older adults using doctor’s prescription records to minimise memory bias.

Since the data were mainly obtained by SPMS from national records (which allowed for a more representative sample of the population) and by sampling according to the patient’s national health number in most health regions, we avoided over-representation of frequent users of primary care services (normally the ones with a higher number of morbidities and medication).

Statement of overall findings

The study results show a high prevalence of polypharmacy in the Portuguese older population (77%), exceeding the reported prevalence of other studies (30–70%) [5]. One of the explanations can be the period of time we used in this study (12-months), which can increase polypharmacy [21], making this high prevalence misrepresentative of reality, since medication could have been ceased. We used a more prolonged period of time because we believed it would allow differentiation between chronic and acute medication, done by evaluating the number of times each medication was prescribed in order to obtain a more accurate value [22]. Further research is needed to better assess which methodology is more suitable, a 12-month or a 6-month period.

Another possible explanation is that we assessed the prescribed drugs and not the ones that were dispensed or consumed by the patient (therapeutic adhesion). This may be misrepresentative of reality; patients could have stopped taking their medication (due to adverse effects, financial problems, etc.) and not have informed their doctor. On the other hand, we did not consider over-the-counter medications and the medications prescribed without the use of the electronic program PEM (e.g. manually), which may have a residual effect.

It is likely that differences in the rate of polypharmacy can be found at the prescriber level [14]. This variation could be explained by practitioners single-handedly treating diseases and illnesses and the lack of guidelines regarding polypharmacy or its prescription [23]. However, efforts to address polypharmacy within evidence-based deprescribing guidelines are being pursued [24].

In line with previous reports [11, 25, 26], we found a significant association between increased age and prevalence of polypharmacy. This could be due to the increase in the prevalence of age-related chronic diseases, which are accompanied by an increase in medications and possibly also because of prescribing for social problems [27]. However, in our new definition (≥ median number of drugs taken) there was not a significant association between increased age and prevalence of polypharmacy. This could be due to the increase of the threshold of polypharmacy that can prevent labelling older adults with polypharmacy just because of the increase of comorbidities and drugs that may be necessary for them, commonly referred to as appropriate polypharmacy, as suggested by Steinman et al. [3].

There was no difference in risk of polypharmacy between genders with the common definition of polypharmacy. Our findings were in line with those of other studies [11, 28]. However, there are studies that found an increased risk of polypharmacy in men [26] and women [14, 25]. A higher prevalence of polypharmacy was also present in our study when we considered polypharmacy as a value equal to or greater than the median number of drugs (≥ 8) taken by the population. One explanation can be that women tend to live longer than men, hence having more chronic health problems and needing more drugs. However, more studies are needed to assess whether there is a difference in risk of polypharmacy between genders.

As expected, the number of chronic health problems affects the number of medications taken by the patient and this association has been well described in the literature [11, 14, 25, 28]. However, in our study there were some chronic health problems with a stronger impact on the risk of polypharmacy, for example group classification D (digestive problems) for polypharmacy as ≥ 5 drugs and K (cardiovascular) for our definition (≥ the median number of drugs taken).

A higher number of prescribers per patient was associated with higher risk of polypharmacy, namely for the common definition (≥ 5). One explanation is that having multiple prescribers may unknowingly duplicate or induce contraindicated medication regimens due to lack of information available, which increases the risk of serious adverse drug events [29]. On the other hand, more complex patients (with multimorbidity) need to be assisted by more doctors and take more drugs. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to assess the impact of having multiple prescribers on polypharmacy.

In agreement with previous reports [14, 26], cardiovascular, metabolic and musculoskeletal medications were the most common in our study sample. This is in line with the most common chronic health problems described in Portugal [19], which are cardiovascular (such as lipid disorder and hypertension), metabolic (such as diabetes and obesity) and musculoskeletal (such as back pain syndrome, osteoarthritis and osteoarthrosis) problems [30]. This highlights the importance of prescribing the best drug option for the patient.

Our proposed definition had better specificity in detecting PIM than the common definition, which means a much lower number of false positive “results”. This occurred at the cost of diminished sensitivity. However, we found a similar mean number of PIMs in both groups (with polypharmacy and without) according to both definitions. These results are in line with those of Steinman et al. [3], which raises the question of whether we should raise the threshold to avoid the risk of under-use as there does not seem to be a greater risk of inappropriate prescription. The advantage of our definition compared to others that propose a higher threshold is that it is not a rigid definition and can be adapted to a specific population morbidity burden, since different populations have different needs. Therefore, it would be like standardizing the risk of inappropriate prescription according to the population’s morbidity burden to help us compare the impact of different health systems and policies on this problem.

There are some limitations in this study.

Firstly, we used a 12-month period to assess the chronic prescribed medication, which can increase the prevalence of polypharmacy, since medication could have been ceased or not purchased (non-compliance). Therefore, the number of medications per older adult may be overestimated.

Secondly, since the SPMS could not provide us with data from both autonomous regions (Madeira and Azores), representing 1.7% of the sample, data were collected by local GPs, making the sample and data processes in these two regions different from the rest. Nevertheless, randomisation was performed for these data.

Thirdly, we intended to evaluate the effects of level of education on polypharmacy. This was not possible due to lack of information in the patients’ electronic records.

Fourthly, the sample size was chosen to achieve a sufficiently precise overall proportion estimate of polypharmacy in the Portuguese older adults’ population, but not to find differences among different population strata.

Fifthly, we could not find any study using an approach like ours (polypharmacy as ≥ median number of drugs taken by the population) and had great difficulty making comparisons between different studies.

Sixthly, we could not have data on over-the-counter medications, so the prevalence of polypharmacy may be underestimated.

Finally, this was a cross-sectional study and so no causal relationship could be proven, and we could not study the health consequences of polypharmacy, namely drug-drug interactions and adverse drug reactions. Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed to understand whether these factors are responsible for the prevalence of polypharmacy. However, we intended to study prevalence and raise questions and not determine causality, so other studies are required to study causality, frequency and outcomes.

In conclusion, this study found a high prevalence of polypharmacy in the studied sample; the most important factors were number of chronic health problems and number of prescribers in both used definitions and age in the most common definition and being female in our new definition.

Polypharmacy should consider medical constraints, pathological needs and patients’ feelings and fears, implying future studies on the accurateness of prescription and the need of deprescription.

We think that our new definition of polypharmacy is of relevance for practitioners since it will identify patients with higher risks. However, further studies are needed to increase its reliability and usefulness.