Introduction

There are no guidelines regarding perioperative fluid therapy for patients with end-stage renal failure (ESRF) [1]. Nearly all the studies of perioperative fluid therapy excluded patients with ESRF because of their physical condition [2–7].

Vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis predispose patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) to dramatic fluctuation of blood pressure in the perioperative period [8]. Hypotension may be caused by restriction of intravenous fluid therapy and by the inhibitory effects of anaesthesia on circulation, aggravating hypotension [8]. The administration of propofol and remifentanil may accentuate these problems [9]. The rational administration of drugs may help avert hypotension, but this may be insufficient [9]. For patients with SHPT, infusion volumes (mainly preoperative solute loads) should be carefully monitored [10]. To assess fluid status, noninvasive haemodynamic monitoring may be applied using, for example, a continuous noninvasive arterial pressure monitoring system (CNAP) [10]. CNAP can improve blood pressure control during dialysis, resulting in a reduction in hospitalisations and without patient discomfort or vascular injury [11]. A previous study showed that continuous non-invasive arterial pressure monitoring in dialysis patients was equivalent to that of invasive blood pressure measurement [12].

Goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT) is based on the changes in stroke volume (SV) and cardiac index (CI) and has attracted much attention recently [13]. GDFT optimises haemodynamics and oxygen delivery [13]. Monitoring pulse pressure (PP) variation (PPV) may be more accurate than monitoring cardiac preload in patients on mechanical ventilation [13]. No studies have confirmed the impact of pathological changes in ESRF patients, including changes in increased pulmonary capillary permeability, calcification abnormalities, and cardiovascular dysfunction, on the use of PPV.

GDFT can facilitate fluid management according to individual demographics and medical status, and it may be useful for the management of patients and SPTH and ESRF during surgery. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the intraoperative fluid volume given to patients with SPTH and ESRF undergoing parathyroidectomy.

Material and methods

Patient population

We recruited 105 ESRF patients with SHPT, who were scheduled for parathyroidectomy at our hospital between August and December 2018. Patients with primary hyperparathyroidism, severe pulmonary hypertension, arrhythmia, atherosclerosis, aortic stenosis, or chronic cardiac dysfunction were excluded. Patients with upper limb oedema or malformation, or with a blood pressure difference of > 10 mm Hg between the arms, were excluded. In total, 3 patients were excluded from this study. All patients were receiving haemodialysis thrice weekly or daily peritoneal dialysis. The patients had an American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status of III. Patients were randomised into two equal groups by a computerised random number generator (managed by a third-party statistician): a control group, managed with a restricted-fluid regimen (restrictive group), and a PPV group (GDFT group), which was given normal saline infusion, and they were monitored for changes in PPV (Figure 1). The same operative team performed all operations.

Anaesthesia and mechanical ventilation

No sedative or analgesic drugs were administered before anaesthesia induction. Dialysis was performed on the day before surgery. After their arrival in the operating room, the patients received routine monitoring, including pulse oximetry (SPO2), electrocardiogram, bispectral index (MedTronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and end-tidal CO2. All patients in the study received CNAP, regardless of grouping. CNAP (CNSystem, Medizintechnik, Graz, Austria) was established and calibrated to measure blood pressure and other haemodynamic variables. This system measures blood pressure continuously in real-time, in the same way as with invasive arterial catheter systems, but it is noninvasive. It provides data about stroke volume, cardiac output, and arterial stiffness. The CNAP system uses a three-component probe attached to the arm, forearm, and fingers. Continuous blood pressure was monitored with the assistance of the finger sensor, and an upper arm cuff measured blood pressure every 15 min. The probes were placed on the arm without arteriovenous fistula.

General anaesthesia was induced in all patients with bolus infusion and a target-controlled infusion of propofol (Fresenius Kabi AB, Macclesfield, UK) for a plasma concentration of 3.0–3.5 µg/ml; a bolus of remifentanil (Yichang Humanwell Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Yichang, China) 1.5 µg/kg infused over 30 s; and cisatracurium besylate 0.15 mg/kg (Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, China). After tracheal intubation, ventilation was established with a tidal volume of 8 ml/kg, and the respiratory rate was adjusted to a target end-tidal CO2 of 35–45 mm Hg. Because the operation was performed and completed using minimally-invasive endoscopic-assisted parathyroidectomy, and in order to avoid excessive high airway pressure during the operation, we maintained the tidal volume at 8 ml/kg, which was lowered (but still > 6 ml/kg) only when the airway pressure was too high. Because the patient’s PaCO2 had to remain within 35–45 mm Hg, it did not achieve the criteria of permissive hypercapnia. Anaesthesia was maintained with target-controlled infusion propofol (target concentration: 2.5–3.5 µg/ml), remifentanil (0.2–0.3 µg/kg/min), and cisatracurium besylate (0.05 mg/kg/min, intermittent intravenous injection). The intermittent injection of cisatracurium was based on the patients’ muscle tone during the operation. During the operation, bispectral index values (MedTronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were maintained within 45 ±5 by regulating the infusion rate of propofol. Thirty minutes before the end of the surgery, the cisatracurium besylate infusion was stopped. Propofol and remifentanil were turned off in both groups after wound closure.

The endotracheal tube was removed when the patients were able to follow verbal commands to open their eyes, and after checking for spontaneous respiration, swallowing, fist boxing, and keeping the head up before extubation, and when the T7/T4 ratio was 90%. The patients were kept in the post-anaesthesia care unit for 1 h.

Fluid management

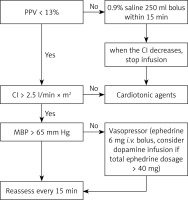

In the restrictive group, only vasoactive agents were administered, without fluid infusion. In the GDFT group, intravenous fluid therapy and the use of vasoactive agents were determined according to the changes in PPV and other haemodynamic variables. If PPV were > 13%, 250 ml of normal saline was administered over 15 min. Fluid responsiveness was evaluated every 15 min. According to the guidelines, fluid was administered appropriately during the parathyroidectomy procedure for patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism. (In our study, all the patients were administrated less than 1000 ml fluid.) Oedema around the incision and pulmonary oedema would indicate that an excessive amount of fluid was given, so the procedure was halted if any of these occurred.

Bradycardia (HR < 40 beats/min) was treated with 0.5 mg of intravenous atropine. Hypotension was defined as a decrease of > 20% of baseline systolic blood pressure (SBP). If hypotension occurred, ephedrine was given in increments of 6 mg. The infusion of dopamine was considered if the total ephedrine dose exceeded 42 mg. Intraoperative dopamine was injected by a syringe pump, and the specific injection speed was adjusted according to the blood pressure value. Hypertension (SBP > 20% of baseline SBP) was treated by an infusion of 10 mg of urapidil. Ephedrine was given in increments of 6 mg to keep mean blood pressure > 65 mm Hg. The cardiac index (CI) was maintained above 2.5 l/min·m2 by intravenously infusing 3–5 µg/kg/min of dobutamine if needed. Additional details of intraoperative fluid management are illustrated in Figure 1.

Study parameters

In both patient groups, demographic data, dialysis history, preoperative complications, duration of operation, the total volume of anaesthetics (propofol, remifentanil, and cisatracurium besylate) used, and intraoperative fluid and vasoactive agents infused were recorded. Postoperative complications, including hypotension, hypertension, pulmonary oedema, infection, incision non-union, and arteriovenous fistula occlusion, were recorded. The patients underwent dialysis 1 day before the procedure. Therefore, the arteriovenous fistulas in the subjects were functional, although some might not have been in good condition. Retrospective analysis after closure monitored this. If closure of arteriovenous fistula occurred after the procedure, we applied replacement therapy or a short-term dialysis to reconnect the pathway, thus ensuring the safety of the patients.

Vital signs and weight were recorded before and after the last dialysis and before the administration of anaesthesia. Baseline SBP was the SBP measured after the last dialysis before surgery. The measurements were taken in the haemodialysis ward before transfer to the operating room. The SBP was measured in the supine position. Values were considered “maximum”, “minimum”, or “baseline”. Haemodynamic variables were continually recorded at baseline (T0), before induction (T1), after induction (T2), immediately after intubation (T3), at the beginning of mechanical ventilation (T4), before incision (T5), at 30, 60, and 90 min during the operation (T6, T7, T8), and at 120 min during the operation or at the end of the operation if the operative time was > 120 min (T9).

Blood samples were taken from the femoral artery before and 30 min after the operation and were analysed for brain natriuretic peptide, blood gases, haemoglobin/haematocrit, lactate, and electrolytes.

In order to preserve the integrity of the arteriovenous fistula, we avoided any blood pressure monitoring and punctures to the arm with the fistula. We used the lower extremity venous access, placed the arm with the arteriovenous fistula on the side of the body, and the nurse repeatedly confirmed that there was no compression of the venous fistula. Any abnormality in the arteriovenous fistula pulsation was assessed before and after the operation, in order to ensure functional integrity.

The primary endpoint of this study was the occurrence of hypotension after operation. The secondary endpoints were the total volume of fluid administered, the doses of vasopressors used, the occurrence of postoperative complications, abnormalities in blood gas values, and electrolyte levels.

Hypotension was considered when blood pressure was lower than the baseline blood pressure by 20%. Hypertension was considered when the blood pressure was higher than the baseline blood pressure by 20%. Pulmonary oedema was considered in the presence of hypoxaemia, foamy sputum, double lung wet rales, and confirmation by chest X-ray. Infections were confirmed by elevated C-reactive protein levels. Poor wound healing was defined as incision oedema.

Statistical analysis

According to the records of the research centre, postoperative hypotension rarely occurs in patients receiving dynamic fluid replacement, while postoperative hypotension is prone to occur with conventional surgery. Therefore, the difference in postoperative complications between the two groups was estimated at about 20%. Postoperative hypotension was also considered in the calculation process of the minimum sample size. A sample of 44 patients in each group was required to detect a 20% reduction in postoperative hypotension at a significance level of 0.05 and power of 80%. Considering a possible 20% dropout rate, a minimum of 53 subjects per group was required.

Statistical analysis were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The data were tested for normal distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and for homogeneity of variances with the Levene test [14]. Normally distributed continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, and those with abnormal distributions were expressed as median (25th–75th percentiles). Categorical variables were expressed as numbers (%). The independent samples t-test was used to compare the continuous variables between the two groups, and repeated-measures one-way ANOVA was used for within-group comparisons. All categorical data were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Comparisons between ranked data were made using the Kruskal-Wallis test or the Wilcoxon test.

Ethics

The study was a single-blind randomised controlled trial. It was conducted at The Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China between August and December 2018. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Trials of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (approval No. PJ-YX2018-008(F1)). Written, informed consent was obtained from each patient. This trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR1800017302). This manuscript adheres to the applicable Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 105 patients with ESRF and SHPT undergoing parathyroidectomy were initially recruited for the study between August and December 2018; three were excluded, as illustrated in Figure 2. Thus, 102 patients were randomised (51 in the restrictive group and 51 in the GDFT group) and completed the study. Patients in both groups had similar baseline characteristics and comorbidities (Table I).

Table I

Patient characteristics and preoperative profiles

Intraoperative profiles

The patients received total parathyroidectomy and re-implantation of a small parathyroid fragment subcutaneously in the femoral area to maintain normal hormone levels. Their intraoperative profiles are listed in Table I. The median duration of operation was similar between the two groups (GDFT group, 122 ±18.3 min; restrictive group, 117 ±15.5 min). The patients in the GDFT group received significantly more saline infusion (median 364 ml, range: 219–408 ml) than did patients in the restrictive group (median: 50 ml, range: 50–50 ml; it was used to maintain the infusion of intravenous anaesthetics (p = 0.001). The patients in the restrictive group received more ephedrine than did those in the GDFT group (27/51 (52.9%) vs. 16/51 (29.4%)) (p = 0.027). Three patients in the restrictive group (5.9%) also required a continuous intravenous infusion of dopamine (they received 10, 20, and 38 mg, respectively), whereas none in the GDFT group needed dopamine. The total volume of anaesthetics used was similar between the two groups. There was no significant difference in blood loss between the two groups, and no patient required transfusion.

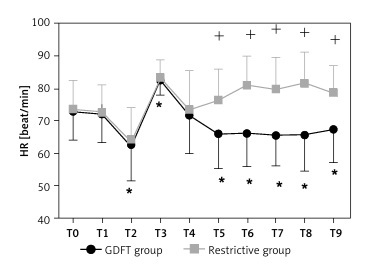

Figure 3 illustrates the perioperative haemodynamic changes that occurred in the two groups. The haemodynamic variables had no significant difference at baseline (T0) or before induction (T1). Compared with the baseline values, the changes in haemodynamic variables at the time of after induction (T2) and immediately after intubation (T3) were mostly similar in the two groups. At the time of mechanical ventilation (T4), SBP was slightly but significantly lower, while diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean blood pressure (MBP), and heart rate (HR) were not. After the initiation of mechanical ventilation, the PPV value was similar between the two groups (12.6 ±6.0% vs. 11.6 ±7.3%; p = 0.417), but after three fluid challenges (T6), the PPV was lower in the GDFT group than in the restrictive group (8.9 ±2.8% vs. 11.6 ±5.1%; p < 0.001). The PPV remained lower in the GDFT group than in the restrictive group for 120 min or until the end of the operation (T9) (7.5 ±2.1% vs. 11.4 ±5.3%; p < 0.001). SBP, DBP, and MBP were significantly lower throughout much or all of the operative period (T5-T9 or T7) in both patient groups than at T0. Throughout T5-T9, SBP was significantly higher in the GDFT group than in the restrictive group, whereas HR was higher in the restrictive group than in the GDFT group; PPV was significantly higher in the restrictive group than in the GDFT group at these time points. CI was significantly higher in the GDFT group than in the restrictive group at T6, T7, and T9.

Figure 3

Differences in haemodynamic variables between the two groups at times during the perioperative period

SBP – systolic blood pressure, DBP – diastolic blood pressure, MBP – mean blood pressure, HR – heart rate, CI – cardiac index, SV – stroke volume, SVR – systemic vascular resistance, T0 – baseline, T1 – before induction, T2 – after induction, T3 – immediately after intubation, T4 – at the beginning of mechanical ventilation, T5 – before incision, T6 – 30 min, T7 – 60 min, T8 – 90 min during surgery, T9 – 120 min during surgery or at the end of the surgery if the surgery time was less than 120 min. *Significant difference, at p < 0.05, from baseline (T0) for SBP, DBP, MBP, and HR, and from the beginning of ventilation (T4) for PPV, CI, SV, and SVR. +Significant difference, at p < 0.05, between the two groups.

Postoperative complications

As the primary endpoint, the occurrence of postoperative hypotension was lower in the GDFT group (0/51; 0%) than in the restrictive group (6/51;11.7%) (p = 0.027). Postoperative hypertension levels in the GDFT group (18/51; 35.3%) and the restrictive group (17/51; 33.3%) were similar (p = 0.500). Arteriovenous fistula occlusion was lower in the GDFT group (0/51; 0%) than in the restrictive group (8/51; 15.7%) (p = 0.006). Among those 8 patients, one had preoperative diarrhoea, two had a long history of hypotension (mean systolic blood pressure 70–80 mm Hg), one had long operation time (> 3 h), one had preoperative damage to the arteriovenous fistula, and one had diabetes-related vascular disease; the reason could not be identified in the remaining 2 patients. In addition, 1 patient in the restrictive group suffered from myocardial infarction after surgery. Although this was not a complication as per study design, this could be related to intraoperative haemodynamic changes. The patients with complications were fewer in the GDFT group (18/51; 35.3%) than in the restrictive group (28/51; 54.9%) (p = 0.047). No patient suffered from pulmonary oedema, infection, or incision non-union (Table II).

Table II

Intraoperative profiles

Baseline and postoperative laboratory tests

The baseline and postoperative values are presented in Table III. A mild but statistically significant drop in haematocrit occurred in the GDFT group (from 39.5 ±5.5 to 37.2 ±5.1, p = 0.034), whereas no drop occurred in the restrictive group. No significant differences in the other laboratory tests were recorded (Table IV).

Table III

Postoperative complications

| Complication | GDFT group (n = 51) | Restrictive group (n = 51) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotension | 0 | 6 (11.8%) | 0.027 |

| Hypertension | 18 (35.3%) | 17 (33.3%) | 0.500 |

| Arteriovenous fistula occlusion | 0 | 8 (15.7%) | 0.006 |

| Others | 0 | 1 (2.0%) | 1.000 |

Table IV

Baseline and postoperative laboratory tests

Discussion

Parathyroidectomy is the most frequently performed operation in patients with ESRF [15], but there are no well-recognised guidelines for intraoperative fluid management. In this study, we aimed to optimise fluid management in patients with SPTH and ESRF undergoing parathyroidectomy. Thus, we used the CNAP system to guide GDFT during the perioperative period. These strategies provided fluid responsiveness to help regulate venous return and CI and to reduce the incidence of hypotension and subsequent adverse events. Previous GDFT studies used invasive monitors under mechanical ventilation [16], whereas we used a noninvasive system. With our protocol, the haemodynamics were well maintained, the use of vasoconstrictive drugs was reduced, and the complications were fewer than in patients managed with conventional fluid management. The protocol is feasible for the fluid management of haemodialysis patients.

Parathyroidectomy can delay the progression of SHPT and improve the quality of life of the patients [17]. Long-term hypertension and hypercalcaemia in patients with SHPT can accentuate their propensity to the dramatic fluctuation of blood pressure in the perioperative period, especially after anaesthesia induction [8]. In this study, more patients in the restrictive group than in the GDFT group had hypotension after operation, as supported by a previous study that reported an occurrence of 19% [18]. Due to preoperative fasting, dialysis, and non-urinary fluid loss, even patients with ESRF may have intraoperative hypovolaemia [8]. Thus, restricted intravenous fluid therapy makes such patients susceptible to hypotension, which can be aggravated by anaesthesia, especially when using propofol and remifentanil [9].

High blood viscosity, low blood volume, endovascular intima damage, thrombosis, and improper care, among others, are all possible reasons for arteriovenous fistula occlusion [19], which is a dismal complication because it can complicate future dialysis. Eight patients in our restrictive group had arteriovenous fistula occlusion compared with none in the GDFT group. It is consistent with evidence that vascular occlusion is one of the most serious complications due to hypotension and unstable blood pressure during surgery [20]. Thus, adequate volume expansion to maintain stable haemodynamics and perfusion is critical. Despite significant associations between the use of GDFT and the lower occurrence rate of postoperative hypotension and arteriovenous fistula occlusion, the exact causal relationship remains to be determined.

Controversy exists over the strategy for fluid management in patients with SHPT during anaesthesia [21]. Some physicians prefer to use no infusion because of fear of fluid overload. Because SHPT patients have variable sensibility to vasoactive drugs, the incidence of hypertension and/or hypotension in them is high [22]. In addition, some drugs used for anaesthesia may reduce the oxygen supply to vital organs [23]. Thus, rational drug use is necessary but may not be enough to maintain normal haemodynamics. Therefore, some authors advocate individualised fluid management during surgery for patients with SHPT [24]. Recent studies revealed associations between hypotension and adverse outcomes such as myocardial injury, depending on the extent and duration of hypotension [25–27]. In non-cardiac surgery, the most common cardiac complication is myocardial infarction, which may be caused by an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand [25–27]. A meta-analysis based on multiple cohort studies showed that intraoperative hypotension increased postoperative major cardiovascular events (OR = 1.56), especially for myocardial injury (OR = 1.67) [26]. Salmasi et al. [27] found that MAP below the absolute value of 65 mm Hg or a decrease of > 20% of the baseline can increase the risk of postoperative myocardial damage. The main goal of perioperative fluid management is optimal microcirculatory perfusion, which can be achieved with well-controlled blood pressure and adequate volume expansion [28]. Some authors suggest that the right amount of fluid can be input during parathyroidectomy, but the absolute amount of liquid should not be fixed [27]. If the amount of dehydration of the last haemodialysis is ≥ 3 kg, patients with normal cardiac function are often accompanied by different degrees of dehydration, but in patients with cardiac insufficiency, there is still the problem of extracellular fluid overload [27]. Therefore, if there is an insufficient capacity before the start of anaesthesia, the blood volume should be replenished in time, and the cardiac function should be considered. Otherwise, huge haemodynamic fluctuations will occur after anaesthesia.

The infusion volume is mainly determined by the preoperative state of solute loads [29, 30]. Thus, it is important to know the patients’ actual weight and dry weight [30]. The dry weight is the lowest weight that can be safely attained after dialysis without hypotension developing [31]. Prolonged low diastolic pressure is one of the independent risk factors for cardiovascular complications [32]. The risk of postoperative pulmonary oedema and hypertension is increased in patients whose weight is higher than their dry weight; this imbalance can impede wound healing and increase the chance of infection [33]. These complications caused by fluid under/over-load are the focus of our research.

Important variations in blood pressure are common during parathyroidectomy [8], possibly leading to cardiac and kidney injury [34], which is of particular concern in patients with end-stage kidney failure. The use of traditional noninvasive blood pressure monitoring using a cuff might cause a delay in detecting blood pressure fluctuations and impair the quick response needed to avert injury; in addition, short periods of hypotension could be overlooked [34]. To achieve and maintain dry weight, the use of noninvasive haemodynamic monitoring, such as with the use of a CNAP monitoring system to monitor the water load in haemodialysis, has been advocated [35]. It first measures arterial blood pressure through the upper-arm calibration system and blood volume and pressure signal through double fingertip-sensors continuously. Then, using the vascular unload technique and VERIFI algorithm, it eliminates the contrast artefact [36]. CNAP can improve blood pressure control between dialysis sessions and limit hospitalisations [37]. In the present study, the CNAP system provided consistent haemodynamic measurements without causing patient discomfort.

Nevertheless, the exact required volume of fluid expansion is difficult to predict and varies among individuals [29, 30]. By providing individualised fluid management, GDFT may help solve this problem. A large PPV or an increase in PPV can be interpreted as operating on the steep portion of the Frank-Starling curve, warning the responsible physician to counteract further fluid depletion to avoid haemodynamic instability [38]. By monitoring noninvasive parameter PPV, this indicator could efficiently assess the fluid requirements of patients with general anaesthesia and mechanical ventilation [39]. MAP, PPV, CI, SVR, and other parameters should be considered comprehensively in patients under general anaesthesia with mechanical ventilation in order to accurately assess liquid reactivity [40]. CNAP can provide real-time PPV monitoring, and CNAP-PPV has identical sensitivity and accuracy to that of invasive methods [41].

In the present study, GDFT strategies based on CNAP-PPV enabled fluid responsiveness to optimise venous return and CI to reduce the occurrence of hypotension and subsequent adverse events. The GDFT strategies we used in the present study reduced the total dosages of vasopressors administered, thus reducing the heart rate, which can be increased using ephedrine and dopamine. Furthermore, after moderate fluid expansion, haematocrit decreases, and haemoconcentration seems to be improved. As verified by our data, the excessive use of vasoconstriction drugs without adequate fluid loading may further induce vasoconstriction, which may cause serious complications after surgery, similar to an arteriovenous fistula. Avoiding puncturing and inserting a catheter in an extremity arterial vessel for anaesthetic monitoring or blood sampling is an important intrinsic advantage of the strategy proposed here. Indeed, these patients may require a new arteriovenous fistula in the future. The use of the CNAP system in these renal insufficiency patients is not yet totally endorsed and might therefore be questionable. However, the current study results with a detailed evaluation of the patency of the AV-fistula before surgery demonstrate its usefulness. Moreover, a former study showed that continuous non-invasive arterial pressure monitoring in dialysis patients was equivalent to that of invasive blood pressure measurement [12]. This previous study used the HASTE system, while the present study used the CNAP system, but both systems rely on the same principles for blood pressure monitoring.

We acknowledge that this study has limitations. Because there is little bleeding and the operation time is short with parathyroidectomy, the results may not be applicable to major operations. Some patients on haemodialysis have arteriovenous fistulae on both arms, or severe arrhythmia, so our protocol will not apply to them. The dry weight of the patients and their weight gain after surgery were not recorded. Our anaesthesia team only observed the condition of haemodialysis on the first day after surgery, and subsequent observation and treatment were not included in the study.

In conclusion, in the present study, PPV-guided GDFT with the CNAP system during parathyroidectomy in ESRF patients is probably feasible and might be reliable. The GDFT protocol reported in this study could help maintain haemodynamic stability, reduce the requirements of vasopressors, and decrease the occurrence of postoperative adverse events.