Introduction

Influenza is a viral infection that may affect almost every organ. International guidelines on preventing influenza strongly emphasize that children under 5 years of age, and especially under 2 years of age, are at a higher risk of a more severe course of the disease, including complications [1]. Morbidity amongst children is higher than in adults and reaches up to 20–30% [2]. In the Northern Hemisphere the epidemic season ranges from October to April. During the 2015/2016 epidemic season in Poland over 4 million influenza cases were reported, including 16 thousand hospitalizations and 140 deaths [3]. The risk of hospitalization is almost 3-fold higher in children under 2 years of age than in older children, but still the highest number of reported influenza cases is found among children under 14 years of age [3–5]. The routine influenza diagnostics is based on a positive rapid influenza diagnostic test (RIDT) result [6, 7] or molecular diagnostics (polymerase chain reaction – PCR). A negative RIDT result cannot be conclusive due to the low, suboptimal RIDT sensitivity [6–8]. The sensitivity reaches 47–70% [6], yet there are publications reporting much lower sensitivity (23%) [9]. On the other hand, PCR shows high sensitivity (85–96%) and specificity (7.6–100%) [10–12]. Independently of the diagnostic path, the treatment needs to be implemented as soon as possible [6]. What is more, clinical suspicion of influenza may be misleading, and frequently the final diagnosis of influenza is surprising, especially in younger children – fever, for example, is present only in 48–70% of patients under 6 months of age [6, 13]. That also contributes to the higher costs of diagnostics and frequently unnecessary treatment (e.g., antibiotics). The global economic influence of influenza seems to be underestimated [14], but the rough estimates suggest a cost between € 0.3 and € 2.7, with an average of € 1.4 billion in Italy (ca. 60 million citizens) [15], for example, while in specific epidemic seasons it may increase: in Germany, during the 1996 epidemic season, the total assessed cost reached € 2.6 billion [14]. The cost of influenza increases when complications are present; in a US analysis the costs were doubled in patients with complications [16].

Material and methods

The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

During the 2015–2016 influenza epidemic season 163 children (87 male, 76 female) aged 16 days to 202 months (median 17 months, 95% CI: 38.3–47.8) were diagnosed with influenza at the Department of Pediatrics of the Bielanski Hospital, Warsaw. Out of 163 patients, 6 were not hospitalized for a period longer than a few hours (patients discharged at parent’s request or transferred to another hospital directly from the emergency ward due to the lack of room at the Department of Pediatrics) and they were not included in the further analysis. Finally, 157 children (84 male, 73 female) were eligible for the study.

Eighty-six patients were referred to the hospital from ambulatory care (55%), 27 required intervention of emergency medical services and were transported with an ambulance (17%), while 44 showed up at the emergency room without prior examination (28%). There were 112 (71%) cases of influenza type A and 28 (18%) cases of influenza type B; in 17 (11%) cases both A and B type of influenza were diagnosed using the PCR method.

The diagnosis of flu was initially made upon clinical signs and symptoms, but in order to avoid an incorrect diagnosis, in each case it was confirmed with the RIDT and/or PCR. Often, the final diagnosis could be made using PCR, due to the low RIDT sensitivity (observed in that season). For each patient, the routine clinical path was implemented. Because of the different availability and costs of the diagnostic methods, the RIDTs were the preferred method. According to the Polish recommendations [7, 8, 17] RIDTs have suboptimal sensitivity but high specificity. Therefore, due to the easy access, rapid results (about 10 min) and lower costs, nasopharyngeal swabs were taken from patients and the RIDT was performed as the first line diagnosis. As the RIDT has been proven to have high specificity during the epidemic season, it was treated (according to CDC and Polish recommendations) [6, 7] as a confirmation of the diagnosis. In the case of a negative test result, further diagnostics (i.e. PCR) was performed. The PCR was performed at an external laboratory, and molecular testing was available from Monday to Friday. Moreover, in patients with low probability of a positive RIDT result (i.e., a longer period of symptoms before hospital admission) the RIDT was omitted and a sample for the PCR was taken at the beginning of the diagnostic path.

The diagnosis of influenza was made upon the RIDT in 39 cases (25%), including 7 (5%) results confirmed with the PCR, and in 118 (75%) cases upon the PCR. The final diagnosis was confirmed with the PCR in 125 (80%) patients.

It has to be underlined that the vast majority of the recommendations (including Polish) emphasize that waiting for laboratory confirmation of influenza should not delay the implementation of antiviral treatment, but this advice may only be applied in cases when the diagnosis presents no doubts. In each patient, treatment was implemented as soon as possible (a 10-minute waiting time for the RIDT result was not considered as treatment delay). The cases where the lack of laboratory confirmation prolonged the implementation of the treatment were in fact cases where a laboratory confirmation was indispensable to make a correct diagnosis because the clinical course of the disease was not typical for influenza.

The cost-of-illness analysis assessed both the direct and indirect costs, seen from the perspective of the patient, the health care system, as well as the social one. The social and health care system costs were qualified as one group of costs, whereas the socioeconomic impact and the patient’s costs were evaluated separately; then, the total cost of the treatment was assessed for these three groups of costs altogether.

Patient’s direct costs: these were the costs that the patients (i.e. parents or legal guardians) had to bear by themselves and were not reimbursed.

This group of costs includes:

transportation costs (1.1. transport to the hospital and 1.2. at least one per day return transport of the parents/legal guardians between home and the hospital),

medications taken prior to hospital admission (not reimbursed),

additional hospital services charge (charge for bed linen for the guardian: this charge is fixed, approximately € 5.7 per hospitalization).

To calculate the transportation costs, the distance between home and the hospital had to be known. The parents filled out personal questionnaires on admission, yet, due to social considerations, the address declared was not necessarily up to date or real: people often declare their address of registration (in Poland it used to be obligatory to have a permanent address) but live elsewhere. Also, renting flats is frequent, especially among younger people who come to the capital city because of better work conditions, and many flats are rented without reporting, which causes confusion when filling out questionnaires. Although there is no zone or district obligation in the Polish hospital health care system, we assumed that most patients choose the hospital that is closest to their actual place of residence. For the purpose of assessing the distance between home and hospital we put our hospital in the center of a virtual area, from where the distance to the closest children’s hospital was calculated in different directions: to the north (11.1 km), south (9.4 km), west (8.5 km) and east (13.4 km), obtaining a mean distance to other hospitals of 10.6 km. The distance was divided by two to create a theoretical radius of the area of patients’ residence covered by our hospital (5.3 km). Then, with a presupposition that most patients will need to travel half of that distance to the hospital, we created a theoretical model of the distance between their home and the hospital.

The patients were transported to the hospital by an ambulance (each medical transport was reported on admission), by taxi, a private car or public transport. Except for medical transport, other means of transport were not reported and their use was treated with equal probability. The costs were calculated as follows: for medical transport – the cost was evaluated as a public health care direct cost (the patient is not charged in any way for medical transport, if required, and indications for medical transport are not analyzed). The exact cost remains under trade secret, but according to the publically available offers on the price/cost (for patients without public insurance, for example) the cost of medical transport was calculated as € 92.

To calculate the patients’ transport to the hospital by means other than an ambulance, and the everyday transport of the parents/guardians to the hospital, three means of transport were treated equally and assessed as follows: private car use – the official governmental fee for using a private car for business purposes per kilometer multiplied by the number of kilometers (officially 19 eurocents/km) and a parking charge for 2 h in case of admission to the hospital (according to the estimated waiting time at the hospital emergency ward) or a charge for 1 h in the case of everyday transport to the hospital; the taxi fare was calculated based on the urban taxi fares); for public transport the cost of two single tickets was assumed (€ 2). Warsaw is one of the European cities with the highest number of cars (circa 600/1000 inhabitants).

The costs of medications were assessed as follows: referring to Damm et al. [18], we assumed that a patient typically needs (prior to hospital admission): nasal spray (one bottle of normal saline and one bottle of an oxymetazoline drug) – if coryza was reported, cough medicine (one bottle of ambroxol and one bottle of butamirate drops) – if cough was reported; an antipyretic drug (we propose both paracetamol and/or ibuprofen – one bottle of 100 ml) – if fever was reported. The lowest possible prices were searched in five different online pharmacies (as of September 2016).

In order to estimate the indirect patients’ costs, certain assumptions needed to be made:

hospitalized children have the right to be taken care of by at least one parent/legal guardian;

parents have the right to obtain a sick note for the period required to cure the patient;

when on sick leave, social security pays the employee only 80% of the salary, and additional insurances covering the income lost due to a disease are in Poland rather uncommon and were not taken into consideration;

the Masovian district (where Warsaw is located) has a higher median income than other Polish regions, so the mean salary in Poland would be misleading here. Thus, to calculate the indirect costs of hospitalization the mean salary in the Masovian district (according to the Polish Central Statistical Office) was used. The parents were not bothered with questions concerning their personal income or social status, and there was no differentiation between mothers and fathers (in general, earnings of men in Poland tend to be higher), as the Central Statistical Office reports mean salaries for both genders [19]. For each day of hospitalization (i.e. work day lost) 20% of the median salary in the Masovian district was counted as the indirect parental cost.

Cost for the medical health care system may be calculated in two different ways: from the payer’s point of view (in most contracts a fixed sum, independently of the length of hospital treatment for a hospitalization exceeding 3 days; independently of the therapy used, diagnostics made, in certain cases dependent on the occurrence of complications if they influence the main diagnosis). The other point of view for such estimations would be to calculate the real cost of hospital treatment, which mainly depends on the length of hospitalization – in this case there is no general agreement between hospitals and the payers, so we used the publically announced (by the hospital management) charge per person per day of treatment for patients who are not insured (in general, this charge is supposed to reflect the mean cost of treatment at various hospital wards). We chose the charge per day method, because it is closely correlated with the presence of complications and does not depend on the local and national health care paying policies. There are many discrepancies on how medical procedures should be calculated and reimbursed to the hospitals, and many controversies are raised, pointing out the underestimated medical procedures as one of the reasons for the debts of public hospitals in Poland. To remain objective, the study made the assessment as explained above.

Another cost of the health care system is an ambulatory care visit. Certainly, there are differences in primary health care access as well as individual differences in the way the parents cope with the disease, but we made an assumption of the number of visits needed before hospital treatment: if the patient was referred to the hospital, the cost of this visit was added to the health care system costs; if the patient presented signs and symptoms for a longer period of time (i.e., at least 6 days), then the cost of an additional ambulatory visit was added. In each case, the number of visits was multiplied by the mean charge for patients who are not insured (which, again, is supposed to reflect the real cost of such a visit). To make the calculations clearer, we assumed that parents did not pay for any private visits, as in an ideal health care system these visits should be covered. Evidently, the private sector of health care is dynamically developing in Poland, especially in bigger cities like Warsaw, but the number of private visits (as well as their costs) was not taken into consideration, especially due to the different methods of payment – health care packages, fee for services, employer’s health care programs, private insurance, etc.).

To calculate the societal costs, the number of hospitalization days was treated as days absent from work. The hospital length was multiplied by the mean productivity loss in terms of the gross domestic product loss.

The total cost of hospitalized influenza cases consisted of the patient’s direct and indirect costs, the health care system costs and the societal costs.

Statistical analysis

Statistica 12 (StatSoft) was used to perform the statistical analysis. To determine the data distribution, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used and according to the data distribution type (normal or not normal), the mean (and standard deviation) or the median (and upper-lower centile) was presented. In the case of normally distributed data, the independent-samples t-test was used, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used in the case of not normally distributed data. A p-value under 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The frequency of complications was 57.3% (90 out of 157 patients), and the most frequently observed complications were pneumonia (31%, 49/157 cases) and bronchitis (23%, 35/157 cases). The median age in the group of patients with complications (90 patients) was 17 months (95% CI: 28.9–38.8 months) vs. 17 months (95% CI: 44.5–62.7) in the group without complications, and it was statistically insignificant (p = 0.74).

Patients with complications required longer hospital treatment (8 vs. 6 days, p < 0.01). The total cost was € 1042 in complicated influenza cases vs. € 779 without complications (p < 0.01), including the patient’s costs (€ 123 vs. € 94, p < 0.01) and the systemic costs (€ 916 vs. € 690, p < 0.01). The patient’s direct costs (€ 49 vs. € 40, p < 0.01) as well as the indirect costs (€ 73 vs. € 54, p < 0.01) were higher in complicated influenza cases. Similarly, both the systemic direct costs (€ 678 vs. € 508, p < 0.01) and the indirect costs (€ 243 vs. € 182, p < 0.01) were higher in complicated cases (Table I).

Table I

Direct and indirect costs (in euros; €) of treatment of hospitalised children, in groups with and without complications

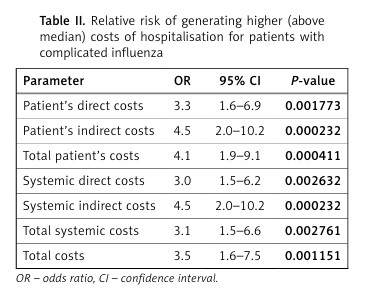

Patients with complications had a 3.5-fold (95% CI: 1.7–7.5, p < 0.01) higher risk of generating higher (i.e., above median) costs, which was especially the case concerning indirect costs (both patient’s and systemic, OR 4.5, 95% CI: 2.0–10.2) (Table II).

Table II

Relative risk of generating higher (above median) costs of hospitalisation for patients with complicated influenza

For the purpose of cost analysis, the patients were divided into two age groups: under two years of age (i.e., under 24 months) and over 2 years of age. To indirectly compare which group of patients was at higher risk of generating higher costs of hospital treatment, we also divided the patients into two other groups: under and over 5 years of age.

Patients under 2 years of age generated a higher total cost of treatment (€ 1101 vs. € 743, p < 0.01), including both the total patient’s cost and the total systemic cost (€ 125 vs. € 86, p < 0.01 and € 997 vs. € 657, p < 0.01, respectively) (Table III).

Table III

Costs (direct, indirect, and total) of hospital treatment of patients under and over 2 years of age (in euros; €)

If the patients were considered as being aged under 5 or over 5, the differences were also significant for each category of costs: total (€ 1026 vs. € 773, p < 0.01), patient’s (€ 114 vs. € 93, p < 0.01), and systemic (€ 905 vs. € 679, p < 0.01). However, the differences observed were smaller: the total cost difference (€ 253 vs. € 358 if the patients were divided based on the age limit of 2 years old), the patient’s cost difference (€ 21 vs. € 39) and the systemic cost difference (€ 226 vs. € 340). These data show indirectly and only in terms of an (inaccurate) economic analysis that greater differences in the costs occur if the age limit is established at 2 years old (Table IV).

Table IV

Costs (direct, indirect, and total) of hospital treatment in patients under and over 5 years of age (in euros; €)

Then, patients were subdivided into different age groups: under 1 month of age, 1–3 months, 3–12 months, 12–24 months, 24–36 months, 36–72 months, over 72 months of age. Here, the highest total cost was seen in neonates (€ 1293), followed by the group aged 3–12 months (€ 1151), 12–24 months (€ 1042) and 1–3 months (€ 1032), and then = 7 years old (€ 873), 24–36 months (€ 853) and 3–6 years old (€ 641). The observed differences between the groups are not large (except for the neonates) within the first 2 years of life, and then costs drop rather radically (Table V).

Table V

Costs (direct, indirect, and total) of hospital treatment in age groups (in euros; €)

Discussion

The study aimed to give an answer to a simple question: is influenza really a self-limiting, “cheap” disease or does it have a substantial influence on the Polish health care system and economy? There are many limitations of the study. Firstly, we focused only on patients who were hospitalized, but in most of the influenza cases hospital treatment is not required; therefore, this study may only give answers on hospitalization costs, not the general economic impact. Secondly, the method of calculating the costs may seem controversial in many points, but to avoid overestimating the costs, only the lowest (yet real) possible fees were taken into consideration. For the patient’s direct costs: the cost of car use is widely considered to be higher than the cost proposed by the official governmental fees for the use of private cars; also, when public transport is used, often more than one single ticket is needed (for example, both parents going to the hospital with the child who also needs a ticket – in Warsaw, children under the age of 7 may use the public transport for free); the use of public transport for a feverish child is also controversial; in most cases car transport was used; no higher taxi fees were calculated for feast days, etc. Similarly, as minimal as possible use of pre-hospital drugs was considered, no unnecessary antibiotic use was included in the calculations, etc. – which surely also generate higher costs, but we aimed to assess only the minimal costs. The most representative example would be oseltamivir, the cost of which could have been added to the patient’s cost, as many patients continued the treatment at home (after the initial hospital treatment) and had to buy oseltamivir (which is not sold separately, only in e.g. 3 single doses). The patients were not asked in a follow-up survey about any long-term complications or other influenza-related infections (otitis media or pneumonia after influenza, for example), but the assumption was made that hospital treatment was enough for a complete recovery. Similarly, there may have been many differences in the costs between the countries and social systems. In Poland, parents/legal guardians receive only 80% of their salary when taking care of a sick child (when confirmed by the doctor’s sick note) for up to 60 days per year (irrespectively of the number of children), while in Germany for example, the reimbursement of 70% is paid, only up to 10 days per child per year [18].

Certainly, socioeconomic costs vary significantly among countries, as well as depending on the calculation method used. Here, only the lowest costs were presented, although the authors are aware that the socioeconomic costs of influenza hospitalizations are much higher, yet hard to calculate.

Authors analyzing the complications in children and the correlation of them with higher costs mainly focus on outpatient treatment – according to Ehlken et al. [14], complications and a severe disease course are seen in 54% of children, which increases the cost almost 3-fold [€ 149 (±278) vs. € 55 (±116)]. In our group of patients, the costs of hospitalized cases were much higher (€ 1042 vs. € 779), because we focused only on patients hospitalized. This comparison reflects the gravity and dimension of the increasing costs in the case of hospitalization.

The frequency of complications differs, depending mainly on the setting of the study (for example, pneumonia and wheezing are more commonly reported in hospital- or ED-based studies, while febrile seizures or respiratory distress is present only in inpatient-based studies) [20]. The most common complications correlated with influenza are acute otitis media (0–41%), pharyngitis (31–58%) and febrile seizures/convulsions (0–45%) [20].

The frequency of complications seen in this group of patients was high, but still it does not reflect influenza’s impact on the diagnostics issues – often, due to the low specificity of the symptoms or signs, the patients are overdiagnosed – a feverish child, especially an infant or newborn, may be suspected of having a septic disease, and a wide range of diagnostic methods, including lumbar puncture, are performed. Thus, influenza not only generates higher costs, but also is correlated with a higher risk of unnecessary use of diagnostic methods, a higher risk of complications associated with them, unnecessary use of antibiotics, etc. [21]. On the other hand, there may be other factors contributing to the disease’s course, especially viral coinfections (with respiratory syncytial virus, human bocavirus, for example), and influenza sampling may be driven by seasonality, thus missing some cases of influenza [22].

Moreover, many authors insist that distinguishing between severe symptoms and the occurrence of complications has no greater impact on the health economics (patients, especially younger children, will in the majority of cases require hospital treatment) [14], but as the present study focused on patients treated at the hospital, this analysis regards more severe cases of influenza than in a huge number of patients who are not referred to the hospital. Therefore, the study focuses on the differences between complicated and non-complicated cases in hospitalized patients, and the differences between these groups of patients are presented above. It also plays a socioeconomic role, since longer hospitalization generates higher costs. Furthermore, given the diagnostic problems mentioned above (the clinical course is often not specific for the flu, PCR is needed to confirm the diagnosis), the general burden of influenza in children seems to be much higher than in the cases recognized upon examination only.

The most effective way of decreasing the costs of influenza outbreaks is vaccination [23, 24]. With the decrease of the number of patients infected and a decrease of complications, the general costs are reduced. There are different vaccination strategies among different scientific committees and countries, but most of them indicate the need for prophylaxis in each child, with a stronger emphasis on risk groups: the American Academy of Pediatrics, as well as the Polish recommendations, underline the need for vaccinating all children, especially those with chronic conditions that increase the risk of complications, and household contacts of those children [1, 25]. Special emphasis is put on children under 2 years of age (inter alia, administering antiviral therapy in patients suspected of influenza). The question may be raised: which group of patients is especially prone to influenza-related complications in terms of selective influenza vaccination through national or regional health programs; for example, what is more cost-effective: vaccinating children under 2 years of age or children under 5 years of age? Of course, optimally, each child would be vaccinated, but our results demonstrate that the costs are higher particularly in children under 2 years of age and then decrease slowly, remaining present in all age groups of patients hospitalized at our ward. In Poland, unfortunately, the general percentage of the population vaccinated against influenza is very low (3.4% in the 2015/2016 season), but is dramatically low in children (0.76% in children under 4 years of age and 0.87% in children aged 5–14 years) [3].

In conclusion, the cost of hospital treatment of children with influenza is high and influenza generates high costs both from the point of view of the care system, as well as the patient. In the case of complications, the costs increase rapidly, again, both from the systemic and the patient’s point of view. When trying to select the age group of children running especially a high risk of generating higher costs of treatment (for example, in order to select the risk group to be vaccinated), we have observed that children under 2 years of age are at the highest risk. The social awareness of the disease severity and costs generated by the disease seem to be alarmingly low, taken into account the extremely low percentage of vaccination against influenza in Poland.