Introduction

The role of mothers has long been the subject of social stereotyping and debate. Psychological and sociological research suggests that women approach this role with a more complex ability to multitask, often prioritising family care over career development [1].

This dynamic became particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when women doctors faced the challenge of balancing their careers, which changed radically overnight, with their childcare and daily care responsibilities [2]. This disproportionate burden, both emotionally and physically, can have long-lasting consequences for women’s academic and professional development, as evidenced by the ever-growing body of research on the wellbeing of women in the healthcare professions [3].

The neuropsychological research mentioned earlier suggests that women approach their professional and maternal roles with the ability to combine multiple tasks at once, often prioritising family care over career development. From an anatomo-physiological perspective, women have been shown to have greater connectivity between the cerebral hemispheres, which allows them to more easily perform different tasks simultaneously [4]. Additionally, increased activity has been reported in the prefrontal cortex – the area responsible for decision-making and concentration. It is these neurological features that allow women to combine work and family responsibilities more effectively, which is probably to some extent related to greater integration between the cerebral hemispheres. According to the data from the above studies, we know that women often prioritise the needs of their loved ones, which may be at the expense of their own rest and rejuvenation.

The different attitudes of men and women towards professional and maternal roles has a significant impact on the career trajectory of women doctors. The available research suggests that women’s tendency to prioritise family responsibilities may limit their ability to advance in their medical careers, as even periodic factors such as fewer publications, lower conference attendance and fewer professional development opportunities may affect their promotion and tenure prospects.

According to the most recent data, it is known that women still face significant barriers to achieving leadership positions in the healthcare industry. While women themselves make up the majority of the healthcare workforce, they remain underrepresented in senior management and executive positions [5]. According to the American College of Healthcare Executives’ 2021 report, women held only 30% of hospital CEO positions, a slight increase from 26% in 2016 [6]. This only proves that, despite some progress, a significant gender disproportionality still persists in senior leadership positions in the healthcare industry. This disproportionate distribution may be due to the persistent public perception of female doctors as less dedicated to their work and less predisposed to leadership [7].

Furthermore, the study focuses on the underlying challenges for women aspiring to leadership positions. Another study conducted in 2020 by the Healthcare Leadership Network of the National Center for Healthcare Leadership indicated that women held only 28% of director of nursing positions – a profession widely considered to be female. This result may be a consequence of implicit biases that favour men in leadership roles, and the challenges women face in building relationships in a male-dominated environment [8].

The historical data are even more notable. In the 1980s, women occupied only around 5–10% of hospital CEO positions, and in the 1990s, women held less than 20% of ward manager positions in the UK National Health Service [9].

These statistics highlight the significant gender gap that persists in decision-making positions in health care, despite the fact that women make up the majority of staff. Urgent action is needed to address this disparity and provide more equitable opportunities for women to rise to senior positions across the health sector.

The survey results also suggest that the challenges women face in balancing their professional and maternal roles are not limited to the clinical setting. Women working in academic medicine, such as university lecturers, also face significant barriers to career progression. A survey of female lecturers at a leading medical university found that women were less likely to be promoted, publish research or receive grants compared to men. These differences were attributed in part to women’s disproportionate burden of family responsibilities, which affected their ability to devote time to research and other academic activities [10].

Despite the passage of time and numerous declarations of equality, the most recent data indicate that women are still underrepresented in senior academic positions in medicine. Although they make up the vast majority of medical school graduates, they are less likely to take up faculty positions and advance to leadership positions in academia [11].

In Poland, the situation does not differ from that in the world’s medical universities. The presence of women in higher academic and managerial positions is still negligible. A report by the Women in Medicine Foundation reveals clear disproportions resulting not only from motherhood [12]. In medicine, women often face stereotypes and restrictions that hinder their career development. Working in hospital wards, being on call at night and being constantly available to patients require a huge amount of dedication. For women who decide to start a family, combining these responsibilities with the role of a mother is extremely difficult. Many struggle not only with physical fatigue, but also (often hidden, but inescapable in today’s world) social pressures that question our ability to fulfil both roles. Taking into account the balance of losses and gains, medical women who decide to start a family often choose specialisations that are not necessarily in line with their dreams or even their predispositions, but which provide them with a reasonably stable life. The results of the report also show that, although women make up almost 75% of medical students, their share of professorial and managerial positions is much lower. However, the situation is improving, with women already accounting for 44% of professors at medical schools in 2021, showing that stereotypes are being broken over time and more and more female doctors are reaching the highest levels of their careers. Combining the roles of doctor, mother, wife and housewife comes with numerous challenges that make it extremely difficult to achieve excellence in all these areas at the same time. Women are more likely than men to experience challenges in balancing professional and parental responsibilities. Many women choose to forgo career advancement in order to have more flexibility to devote time to their families. However, this does not imply a lack of potential to reach top professional positions. On the contrary, numerous examples of successful women show that, with the right support and understanding from employers, it is possible to effectively combine professional and family roles. Support from other women in the same professional environment proves to be particularly important. The increase in the number of women in managerial and professorial positions gives hope that, in time, more of them will have the opportunity to achieve their professional goals without having to choose to sacrifice family life.

It should also be added that the large discrepancy between the majority of women in medical universities and their under-representation in leadership positions is not solely due to gender differences and predispositions. It is significantly influenced by the challenges women face in balancing maternal responsibilities with the demanding nature of academic medicine. Unlike their male counterparts, women in the field are often burdened with the dual expectations of professional excellence and managing the majority of domestic and childcare responsibilities. This imbalance in the division of domestic work can make it difficult for women to devote the same amount of time and energy to academic activities as their male colleagues. Women often experience discrimination in job interviews when they are asked inappropriate questions about family planning or caring responsibilities – topics that are almost never discussed with men. To address this systemic bias, it is important that both partners in a relationship have open discussions about their mutual expectations and the fair division of family responsibilities. An opportunity to improve the situation in Poland is the new provision that gives the possibility to split maternity leave with the father of the child into paternity leave. This allows the mother to return to work earlier and the father to have the statutory 9 weeks of bonding time with the child. This collaborative approach can help women in medicine (not just academia) to cope with the challenges of balancing professional and maternity roles, ultimately enabling them to further their careers in academia.

Material and methods

For the present study, an anonymous online questionnaire was developed to collect data from 534 mother doctors. The 32-item questionnaire focused on the relationship between their careers and family life, covering demographic information, family configuration, availability of home help, division of household responsibilities and the impact of these factors on their professional life. The questionnaire was distributed via email and online messaging to a wide range of Polish female doctors, and participation was voluntary. Responses were collected over a one-month period in August 2024. Frequency analysis was used to interpret the data, in which respondents’ answers were categorised and the percentage of responses in the entire sample was calculated. In some analyses, percentages were calculated for valid observations (those who actually answered the question) rather than the entire sample.

Results

The respondents were women between the ages of 31 and 40, the majority of whom were married with 2 children. The largest percentage of respondents had children aged 3–5 and 6–12 years. The largest percentage of respondents worked in paediatrics or internal medicine and had one speciality. 43.8% of those taking part in the survey worked on-call, and almost 70% of the respondents worked in a hospital. The second most frequently indicated place of work was primary care or a specialist clinic.

The majority of female doctors surveyed (51.7%) stated unequivocally that motherhood had a significant impact on their approach to patients, with 30.7% indicating a moderate impact. The most commonly cited changes at work related to motherhood were a greater understanding of the needs of patients, especially mothers and children (79.1%), as well as increased empathy (59.0%) and changes in communication style (54.7%) with patients.

In addition, a quarter of respondents (25.8%) reported having experienced situations where their personal experiences as mothers directly influenced their clinical decisions. However, almost half (46.4%) said they had not encountered such situations.

The study found that motherhood had a significant impact on the professional development and scientific activity of the female doctors surveyed. More than half (54.5%) indicated that motherhood had limited their opportunities for professional development, while 17.4% said it had motivated them to develop further. Interestingly, 16.5% said that motherhood had only temporarily slowed down their progress, but had also motivated them to pursue new ambitions.

Further analysing the responses of the respondents, it was noted that motherhood also had an impact on scientific activity, but here it should also be noted that more than half (55.1%) of the respondents said that they had never published and did not intend to do so. However, 17.6% publish less or have stopped publishing altogether, and 15.2% said that they no longer have as much time to publish as they did before becoming a mother.

The survey also found that motherhood had a significant impact on the ability to attend scientific conferences, with 37.8% indicating that this made it significantly more difficult, and 47.9% stating that it only made it somewhat difficult for them to attend. The main reasons cited were difficulties in finding childcare (75.4%), lack of support from partners/family (25.4%) and lack of flexibility at work (24.1%).

When asked about the impact of motherhood on their career success, more than 30% of respondents felt it hindered their success or had no impact, while only 4.9% felt it contributed to their success.

Despite the challenges posed by motherhood, it appears that women are able to reach further up the career ladder and achieve professional success after becoming mothers. Almost half of the respondents who answered this question indicated obtaining an additional specialisation/completing a specialisation, passing the PES (National Specialisation Examination) or completing courses or postgraduate studies. Approximately 30% reported obtaining a degree or publishing scientific articles, and 21.1% had attended international scientific conferences.

The survey also explored the impact of multitasking resulting from the dual role of mother and doctor. More than 65% of respondents indicated that such multitasking had a positive impact on their organisational skills and productivity at work, demonstrating that the skills acquired through managing multiple responsibilities can enhance professional performance.

In terms of mental wellbeing, the majority of women interviewed rated their mental health upon returning to work after maternity leave as good or average, with only 11% reporting poor or very poor wellbeing. This suggests that with the appropriate support and coping strategies, many women are able to cope with the challenges of balancing work and family life.

Respondents’ views on the impact of motherhood on their resilience to work-related stress varied, with 37.6% indicating an increase in resilience, 29% a decrease and 33.1% reporting no impact. This highlights the individual nature of how motherhood may affect the ability to cope with work-related stress.

In terms of work-life balance, almost 40% of respondents rated their ability to manage it as average or good, while 10.6% rated it as poor or very poor. These results suggest that while many women find it difficult to achieve a harmonious balance, some are able to successfully manage the demands of their professional and maternal roles.

The survey also identified key challenges faced by mother doctors, with fatigue and lack of energy, difficulty balancing work and home responsibilities, and high stress levels among the most frequently cited issues. These findings highlight the need for greater support and adaptation to help alleviate the unique challenges encountered by this population.

Overall, the survey results demonstrate the complex and multifaceted nature of the relationship between motherhood and medicine. While the challenges faced by this professional group are significant and above standard, this survey also highlights the remarkable resilience, determination and professional success of many women doctors who have become mothers [13, 14].

The survey results also provide valuable information on the health challenges faced by mother doctors. More than 60% of respondents reported health problems related to their work, in particular osteoarticular pain and back pain. At the same time, 56.8% indicated mental health difficulties, including exposure to chronic stress, fatigue, sleep disorders, job burnout, depression or even anxiety disorders. Many of the respondents struggle with physical and mental health problems at the same time, highlighting the complexity of health challenges, pressures and demands placed on this professional group. These findings highlight the importance of peer support for mothers’ mental health and their motivation to be active. These relationships are particularly evident in groups of younger mothers and for women reporting higher career ambitions.

Women participating in the survey most frequently indicated the need for flexible working hours, better treatment respecting their maternity responsibilities and the provision of childcare in the workplace. Introducing these changes could significantly improve their comfort and work-life balance. Many also expressed a desire to reduce evening and on-call working, as well as to reduce total working hours. These suggestions underline the need for more family-friendly policies and facilities that can help alleviate the unique challenges faced by mother doctors.

The survey also asked about the impact of motherhood on respondents’ career ambitions, with almost 30% indicating that it had slightly lowered their ambitions and almost 13% reporting a significant decrease. However, a quarter of the women said that their ambitions remained the same, and 7.7% even felt that motherhood had made them more ambitious and determined. These diverse results highlight the complex and individualised nature of the impact of motherhood on career development in this population.

When asked for advice for younger female colleagues planning motherhood, the most common recommendations were not to delay starting a family, to prioritise family over work and to seek support systems (both personal and professional) to help cope with the demands of work and home life. These suggestions emphasise the importance of work-life balance and the need for a supportive environment for mother doctors.

More than half of the respondents (54.5%) indicated that motherhood had limited their opportunities for professional development. In contrast, around 20% noted that motherhood, although it had temporarily slowed down their progress, at the same time motivated them to set new goals and further their professional development.

Statistical analysis of the association between partner support, maternal perception, maternal age and mental health and work activity

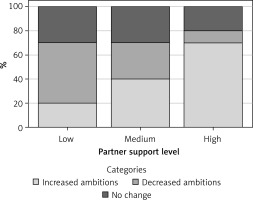

Relationship between stated career ambitions and partner support

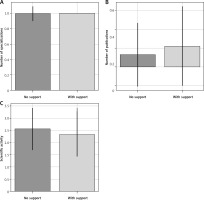

The analysis showed a statistically significant relationship between partner support and declared career ambitions (Figure 1, p < 0.05). Higher levels of partner support were associated with higher career ambitions, while lack of support correlated with a decrease in these ambitions. These results highlight the importance of partner support for women’s career motivation, particularly in the context of motherhood.

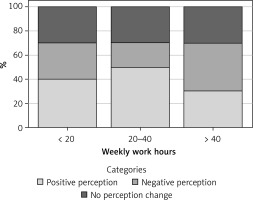

Working time and perception of motherhood

There was no statistically significant relationship between working time dimension, on-call duty and perceived impact of motherhood (Figure 2, p = 1.00). The results indicate that perceptions of maternity may be influenced by other factors, but further analysis is needed to take these aspects into account.

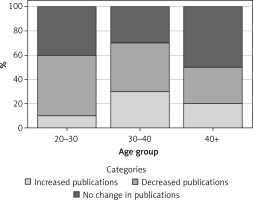

Age of mothers and scientific activity

No statistically significant relationship was observed between the mothers’ age and their scientific activity (Figure 3, p = 0.469). These results indicate that age is not a key factor influencing the scientific activity of study participants. Factors such as the availability of resources to support scientific development, as well as individual preferences and motivations, may play a greater role

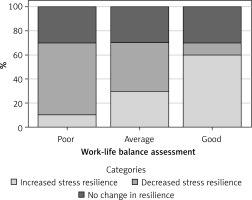

Ability to manage work-life balance and resilience to stress

The analysis examined the relationship between ratings of the ability to manage work-life balance (poor, average, good) and declared resilience to stress (increased, decreased, no change). A statistically significant relationship was found between the ability to manage balance and resilience to stress (Figure 4, p < 0.001). The results suggest that individuals with a better assessment of their ability to maintain work-life balance are significantly more likely to report high resilience to stress. This suggests a strong link between life stability and the ability to manage tension, which may be a key factor in maintaining psychological wellbeing in this professional group.

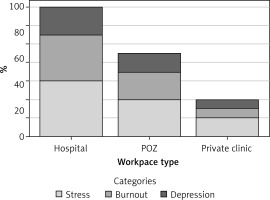

The impact of the workplace on job burnout

The analysis examined the relationship between type of workplace (hospital, primary care practice [PCP], private practice) and respondents’ reporting of mental health problems, such as exposure to chronic stress, job burnout and depression. Workplace type was significantly associated with job burnout (Figure 5, p = 0.0018). Working in a hospital was associated with a higher risk of stress and burnout compared to working in a PCP or private practice. This relationship may be due to differences in workload, organisational pressures and the specific demands of the work environment. These findings highlight the need for psychological support and preventive measures, especially in the hospital environment.

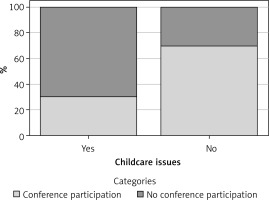

Difficulties in finding childcare and scientific activity

The analysis examined the impact of difficulties in finding childcare on scientific activity, declared as active publication of scientific articles or participation in conferences. Difficulties in securing childcare were significantly associated with reduced scientific activity (Figure 6, p < 0.05). Lack of access to care correlated with fewer scientific publications and lower conference attendance. These results highlight the importance of access to childcare support for active mothers, especially those involved in scientific research.

This analysis indicates that partner support, workplace environment, work-life balance and difficulties in finding childcare may have a significant impact on mothers’ working lives and mental health. The results suggest that the introduction of flexible working hours, psychological support programmes and institutional childcare might improve mothers’ quality of life and work activity. However, this requires further research, taking into account more variables and social determinants.

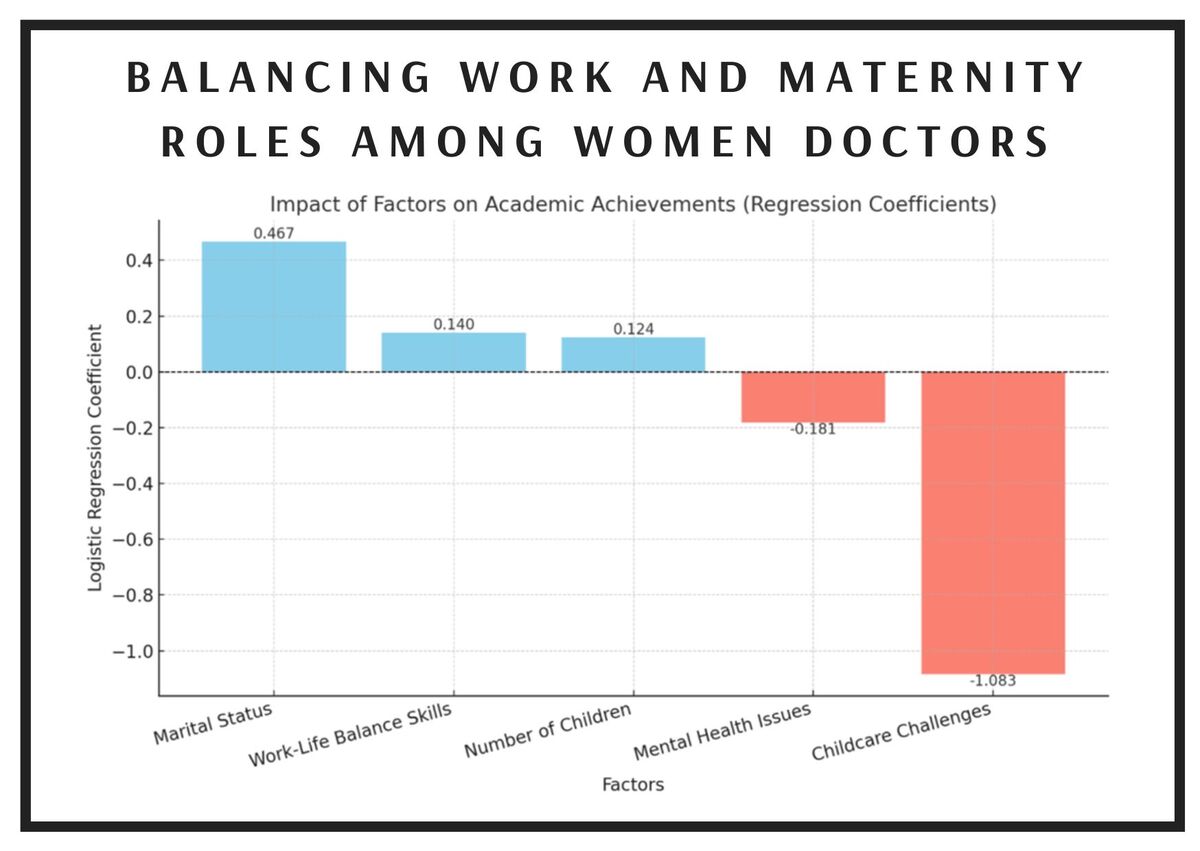

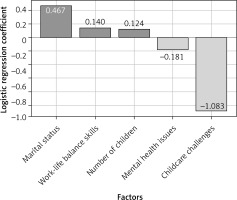

Taking into account all available data, a logistic regression analysis was also carried out, using the respondent-reported information about factors which, according to them, have the greatest influence on hindering career development.

Results of the regression analysis are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7

Logistic regression analysis based on respondents’ views of the main barriers to career progression

Logistic regression analysis identified key factors associated with the academic achievement of mother doctors:

– Marital status (coefficient: 0.467): Marital status, especially the lack of support from a partner or family, significantly increases the risk of reduced academic achievement.

– Ability to manage work-life balance (coefficient: 0.140): Better management of work-life balance helps to mitigate the negative impact of other factors, although its importance is moderate.

– Number of children (coefficient: 0.124): A larger number of children is associated with some difficulty in achieving academic goals, but this effect is relatively small and not statistically significant.

– Mental health problems (coefficient: –0.181): Stress, job burnout or other psychological problems do not show a strong direct association with academic performance, although they may be a secondary effect of professional difficulties.

– Difficulties in accessing childcare (coefficient: –1.083): Lack of access to childcare was associated with a large, statistically significant reduction in opportunities to develop an academic career, including publications or participation in conferences.

The data reveal a worrying statistic: almost 60% of participants reported struggling with mental health problems, including insomnia, chronic fatigue, professional burnout, anxiety and depression. Despite this alarmingly high prevalence of mental health problems, the analysis indicates that stress, professional burnout and other mental health difficulties do not show a strong direct impact on academic achievement (coefficient: –0.181). However, it is possible that they are a secondary effect of the professional difficulties and systemic burdens faced by women in the medical profession.

Paradoxically, many women strive to maintain the high quality of their professional and scientific work despite their mental health problems. This testifies to their great diligence, which is highly valued in a profession of public trust such as medicine. However, excessive sacrifice at the expense of their own health signals a deep systemic problem.

High levels of psychological strain do not reflect individual shortcomings, but are the result of a lack of institutional support and an unequal distribution of responsibilities, especially in the context of difficulties in providing childcare. These problems, although not always directly translated into academic performance, may indirectly affect motivation, cognitive function and long-term work activity [15, 16].

In summary, these findings point to the need to implement comprehensive systemic solutions to support women’s mental health and enable them to realise their full professional potential without sacrificing their own wellbeing.

As some respondents reported receiving a lot of support in the workplace after returning from maternity leave and others strongly denied receiving support from their superiors, the relationship between the two groups of women (those declaring support and those denying it) in terms of career achievements was examined (Figure 8). The results indicate that women declaring support at work do not differ significantly in the number of occupational specialisations compared to women without support. A slightly higher mean scientific publication activity was observed in the group with support. However, this difference did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that support at work is not a key driver of respondents’ scientific activity. Contrary to expectations, women receiving work support report slightly lower academic activity than women without support. This may indicate that work support favours other work activities or balancing responsibilities, and not necessarily academic activity.

Figure 8

Comparison of professional and academic achievements among women with and without workplace support after maternity leave: A – average number of specialized, B – Average number of sientific publications, C – Average scientific activity

The findings of the analysis suggest that professional support after returning from maternity leave does not have a significant impact on the self-realisation and success of the women surveyed. The number of specialisations, involvement in scientific publications and declared scientific activity were found to be similar in both groups. The results suggest that professional development in terms of specialisation and scientific activity may depend on other factors, including support, individual predisposition and working environment conditions.

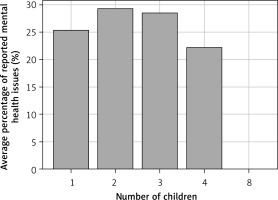

Another important aspect was to investigate how the number of children affects the mental health of mother doctors, especially in the context of chronic stress, professional burnout, anxiety and depression.

It was also investigated whether having more children influences better coping with stress and less frequent reporting of mental health problems, or whether it increases the burden, leading to a higher health burden. The following analysis compares the percentages of reported mental health problems in groups of mothers with different numbers of children and tests for significant relationships between these variables.

The results of the analysis of the relationship between the number of children and reported mental health problems are shown below (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Relationship between number of children and reported mental health problems. c2 = 4.75, p = 0.31

Percentage of reported mental health problems (stress, job burnout, anxiety, depression): Mothers with 1 child: 25.4%, Mothers with 2 children: 29.4%, Mothers with 3 children: 28.6%, Mothers with 4 children: 22.2%, Mothers with 8 children: 0% (one respondent).

The highest proportions of mental health problems were reported by mothers with 2 (29.4%) and 3 children (28.6%), slightly less by mothers with 1 (25.4%) child. The lowest percentage of problems was found in mothers with 4 (22.2%) children, although the number of observations was small. Mothers with more children (4 or more) reported fewer mental health problems, which may indicate a better adaptation to multitasking as well as higher levels of social and family support. However, the group is not representative, and therefore research needs to be conducted with a larger group of respondents to draw further conclusions.

Discussion

The results of the survey demonstrate the complex nature of the relationship between motherhood and medicine. Although the challenges faced by this professional group are significant, the survey primarily highlights the exceptional resilience, determination and professional success of many women doctors who have become mothers.

The results of the survey provide valuable information about the challenges faced by female doctors combining their role as mothers with their professional demands. It is worth emphasising that medical professionals, regardless of gender, are always expected to be fully prepared and available, even though they themselves may be struggling with chronic health problems, which often does not exempt them from their professional responsibilities. Women healthcare professionals in particular face additional challenges due to the physical and mental strain of their demanding careers. Numerous studies have shown that female doctors are more likely to experience professional burnout, depression and other mental health problems compared to men in the same roles. This is often exacerbated by the additional responsibilities of running a home and raising children [17].

The combination of long working hours, a stressful environment and personal health issues can have a significant impact on the wellbeing of women working in healthcare. Many female doctors struggle with conditions such as musculoskeletal disorders, particularly in the joints and spine, chronic pain and sleep disorders, which can further impair their ability to provide optimal patient care. Despite these challenges, female doctors often have limited capacity to take care of their own health, which, over time, can lead to professional burnout and a decline in the quality of both professional and family life. An additional aspect that is often overlooked is the fact that women need more sleep than men to recuperate due to cyclical hormonal differences. Also, frequent night feedings of children or changes associated with menopause at a later stage, often combined with on-call duties, can lead to chronic fatigue, chronic sleep deprivation and insomnia [18].

Despite the increasing representation of women in medical schools, significant obstacles to successful career progression persist. Female doctors are face unwarranted suggestions that their professional commitment is diminished due to family commitments, while their male colleagues are not subjected to similar assessments. This bias, coupled with the time-consuming nature of medical practice and the additional responsibilities of running a home, can lead to professional burnout and a disproportionate reduction in working hours among female doctors in order to manage work-family conflict. The health problems, both physical and mental, previously discussed by respondents, clearly show a link to the social pressures and high demands placed on this professional group.

The survey also asked respondents about their suggestions for changes in the workplace. The most common responses were suggestions for the introduction of flexible working hours, more support in the workplace and the creation of on-site childcare facilities, highlighting the need to implement more family-friendly policies. One potential solution could be to expand initiatives such as hospital-based day care centres, which have been shown to have tangible benefits by increasing work schedule flexibility and job satisfaction among mother doctors. According to research by Harvard Business School, up to 50% of employees aged 26–35 have left work due to care responsibilities [19]. Such absenteeism and staff turnover can have far-reaching consequences, from disrupting team dynamics to increasing recruitment and training costs, as well as putting additional strain on remaining staff due to staff shortages.

Research by health systems in the US suggests that on-site day-care can significantly alleviate these problems. Hospitals such as Wellstar Health had a turnover rate of just 1.5% among staff using on-site day care, demonstrating that such arrangements are an effective tool for staff retention [20]. Additionally, hospitals seeking alternatives through initiatives such as Hospital in Tennessee and Mass General Brigham in Boston have seen a reduction in staff absenteeism and an increase in staff loyalty.

The impact of motherhood on career ambition varies. Respondents who reported a decrease in ambition most often cited a lack of support in the workplace, difficulties in balancing work and family responsibilities and social pressures regarding family roles. In contrast, women who maintained or increased their ambition emphasised the importance of solid systemic support and motivation to be a role model for their children. Respondents’ advice to younger female colleagues planning for motherhood highlights the importance of prioritising family and seeking support to achieve a healthy work-life balance and thrive in a caring environment. This highlights the unique challenges faced by maternity doctors who have to meet the demands of their medical careers while also acting as caring parents. Establishing a supportive network and maintaining a balanced lifestyle are crucial for mother doctors to succeed in both their professional and personal lives.

Respondents’ self-perception, from a professional and family perspective, is another important factor. Fortunately, the majority of respondents felt that their maternity experiences had made them better doctors, challenging the view that motherhood is a barrier to career development. This finding suggests that, with the right support, women can develop as both mothers and doctors, using the skills acquired through maternal responsibilities to improve their clinical practice.

Research in the field of neuropsychology suggests that there are some differences in brain function between men and women that may influence their approach to work and family roles. Women may cope with these roles differently due to both biological and socio-cultural factors. Some evidence suggests that they tend to exhibit strong multitasking ability, potentially supporting the successful management of household and work responsibilities. This increased ability to multitask might allow women to thrive in demanding, multifaceted roles, using their unique neurological characteristics to cope with the complexities of modern life [21].

However, these capacities may affect their career priorities. Women are more likely than men to work part-time to manage caring responsibilities, potentially slowing down their career development. However, these observations highlight the complexity of the issue and the need to take into account the various factors that shape women’s career decisions [22]. It is important to realise that these are only observed trends, and that women as a group show a wide range of skills and preferences when it comes to balancing work and family life. Many women doctors, for example, demonstrate exceptional resilience, determination and professional success despite the challenges of motherhood. With the right support, such as flexible working arrangements, women can thrive as both mothers and professionals, using the skills acquired during motherhood to enrich their professional practice.

Even though tremendous progress has been made over the years, too many of the profession’s ‘glass ceilings’ remain intact. And while there is no shortage of qualified women in leadership positions, with women making up nearly half of the US workforce and outnumbering men in obtaining bachelor’s, master’s, medical and law degrees, men continue to occupy the highest-paid and most prestigious leadership positions, from corporate boards and healthcare management companies to courts, non-profit organisations and universities.

Despite decades of investment in women’s leadership programmes, meaningful progress in women’s leadership development remains elusive. The American Association of University Women seeks to ultimately close the gender leadership gap. Research indicates that workplace culture, unconscious bias, family caregiving responsibilities and inequities in pay and benefits contribute to the underrepresentation of women in senior positions. Women were disproportionately affected by job loss and increased caregiving demands, which were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Academic mothers, in particular, face unique obstacles, including prejudice, lack of family-friendly policies and difficulties in balancing teaching, research and caring responsibilities.

The characteristics of a ‘leader’ and pathways to advancement remain largely rooted in an outdated male model that excludes women. The American Association of University Women (AAUW) has a long history of advocating for the dismantling of the glass ceiling through public policy, research and community initiatives. Given the growing evidence that diversity in leadership enhances organisational performance and innovation, the underrepresentation of women in senior positions is a critical issue for society [23].

Long-standing gender stereotypes persist because men have historically dominated leadership positions and the medical profession. Traits associated with leadership are often seen as masculine, and women who exhibit these traits are not always viewed positively. People tend to assume that men naturally possess qualities such as assertiveness, self-confidence and decisiveness, attributes that are colloquially associated with effective leadership. Conversely, women are still expected to be more submissive, caring and empathetic, which are not considered ‘leadership’ qualities. Nevertheless, many so-called ‘feminine’ qualities, including empathy, cooperation and emotional intelligence, are in fact valuable leadership qualities.

Fulfilling the potential of mother doctors in the health professions requires systemic support that takes into account their unique needs and talents. In the Polish context, practical steps could include:

Developing flexible forms of employment in medical facilities, such as hybrid or task-based working options, to enable better time management.

Coaching programmes where experienced mother doctors can share knowledge and strategies for balancing professional and family roles.

Training in emotional intelligence and stress management to enhance leadership competencies and mitigate professional burnout.

Promoting parent doctors into leadership positions, which can introduce a new quality of leadership based on diversity of experience and values. Instead of treating motherhood as a challenge to the system, it can be used as a source of inspiration and innovation. Mother doctors have the potential to become architects of a more humane and sustainable healthcare system. In the context of the current difficulties in the Polish healthcare sector, investing in their development is not only a response to current challenges, but also a strategy for building a future rooted in collaboration, empathy and sustainable management.

The results of the study clearly indicate that motherhood has a significant impact on the everyday professional life of female doctors, limiting their opportunities for promotion, participation in scientific activities and sense of professional stability. The respondents’ answers show that in the current organisational model, women are often forced to choose between their career and family life, which leads to professional inactivity or overwork. To counteract these phenomena, changes are needed, starting with internal regulations in hospitals and universities, including the introduction of more flexible schedules, scoring of non-measurable activities (e.g. mentoring, teaching) and the creation of programmes to support women during the period around childbirth.

At the institutional level, consideration should be given to introducing temporary reductions in working hours – e.g. until a child reaches the age of 5 – without affecting remuneration and with a guarantee of career continuity. This solution could prevent frequent parental leave, which exacerbates staff shortages, and would give women a real opportunity to maintain a balance between their professional and parental roles [24, 25]. In cases of high-risk pregnancies and births after the age of 35, it is also necessary to extend maternity leave and provide access to targeted medical and psychosocial support for returning to work [26, 27].

From the perspective of Central and Eastern Europe, where women are highly represented in medical professions but still underrepresented in decision-making positions, the proposed changes should include harmonising parental leave policies, ensuring access to workplace nurseries and implementing models for professional reintegration after long periods of absence [28, 29]. At the same time, changing demographics across Europe – the increasing age of women giving birth to their first child – should be taken into account, as this is associated with greater health needs and a greater psychological burden. It is this change that should provide the impetus to accelerate the implementation of policies that genuinely support women in reconciling motherhood with professional life.

In conclusion, motherhood represents a profoundly transformative experience in the professional lives of women doctors, the impact of which goes far beyond stereotypical limitations. Accumulating evidence suggests that mother doctors not only become more organised and resilient to stress, but also develop leadership skills that can contribute to the transformation of the healthcare system in Poland. A key finding is that motherhood equips women with unique qualities such as empathy, flexibility in decision-making and the ability to prioritise, which are fundamental for leaders in challenging, unpredictable environments. Childcare challenges are one of the most significant barriers to academic success for mother doctors. While factors such as marital status and number of children also play a role, their impact is less clear. Many female participants struggle with mental health issues, including lack of sleep, chronic fatigue, job burnout, anxiety and depression. The high prevalence of mental health problems highlights the huge burden these women face, dispelling the stereotypical notion that they can only be overcome by willpower.