Introduction

Intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalizations may be one of the major burdens on the healthcare system. Eligibility criteria for ICU treatment are well defined in most cases, but in practice, the number of hospitalizations in ICUs may vary depending on such factors as financial resources, human resources, medical resources, organization of the country’s health care, and other factors. In a study from the USA, based on hospital discharge data in the State Inpatient Database for Maryland and Washington States, the proportion of hospitalized patients admitted to an ICU across hospitals ranged from 3% to 55% [1]. Hospitalizations in ICUs concern emergencies associated with a sudden threat to health or life. Respiratory failure was reported to be one of the most common reasons for ICU admissions and hospitalizations [2]. Another study revealed the incidence of sepsis in ICUs at 58 per 100,000 person-years, 41.9% of whom died in hospital [3]. Factors found to be important for the prognostic outcome of sepsis in patients hospitalized in ICUs include gender and selected clinical factors and diseases [4].

High mortality rates were reported to be related to ICU care, being 19.0% in the hospital and 21.7% within 6 months [5]. ICU readmission was associated with an increased severity of illness scores during the same hospitalization in adult patients [6]. Another study based on a large dataset of 77,132 ICU survivors reported that 89% of patients returned home, but after 1 year, 77% of patients were still at home and 17% of them had died [7]. Compared to non-ICU patients, ICU patients showed an increased hospital length of stay and mortality. ICU patients were more frequently readmitted to hospital than controls, and mortality up to 1 year in this group was also higher in ICU patients [8]. Compared with late readmission, early readmission was associated with decreased mortality [9]. Readmission to the ICU during the same hospitalization may not be a rare problem. In a study from Brazil, out of 5,779 ICU patients, 10% were readmitted to the ICU during the same hospitalization [10]. A significant proportion of patients hospitalized in ICUs died during hospitalization. Infection at ICU discharge, ICU readmission, age, length of hospital stay, and higher SAPS III values increased the risk of death in ICU survivors [11]. ICU and in-hospital mortality may be reported with considerable heterogeneity. In one study, mortality of older patients (≥ 75 years) admitted to the ICU ranged from 1% to 51%, and in-hospital mortality from 10% to 76% [12]. In a study from India, the most common cause of death among elderly patients was found to be sepsis, followed by pneumonia [13]. In another report, end-of-life care expenditures for the older population with cancer were highly concentrated until the last month [14]. Hospitalizations in ICUs involve costs of care during hospitalization and may be related to costs of post-hospital care. Critical care survivors had greater 1-year post-discharge healthcare resource utilization than non-critical inpatients, including 68% of those with longer hospital stays [15]. In a recent study including data on 19,119 older adults aged 65 years or more who had received high-intensity care at least once and died in the intensive care unit in South Korea, the annual cost of high-intensity care at the end of life increased steadily from 2016 to 2019 [16]. In Poland, ICU admissions are guided by uniform qualification criteria recommended by the Polish Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Therapy (PTAiIT). Guidelines for ICU admission in Poland in the form of priorities were first published in 2012 [17] and recently modified [18].

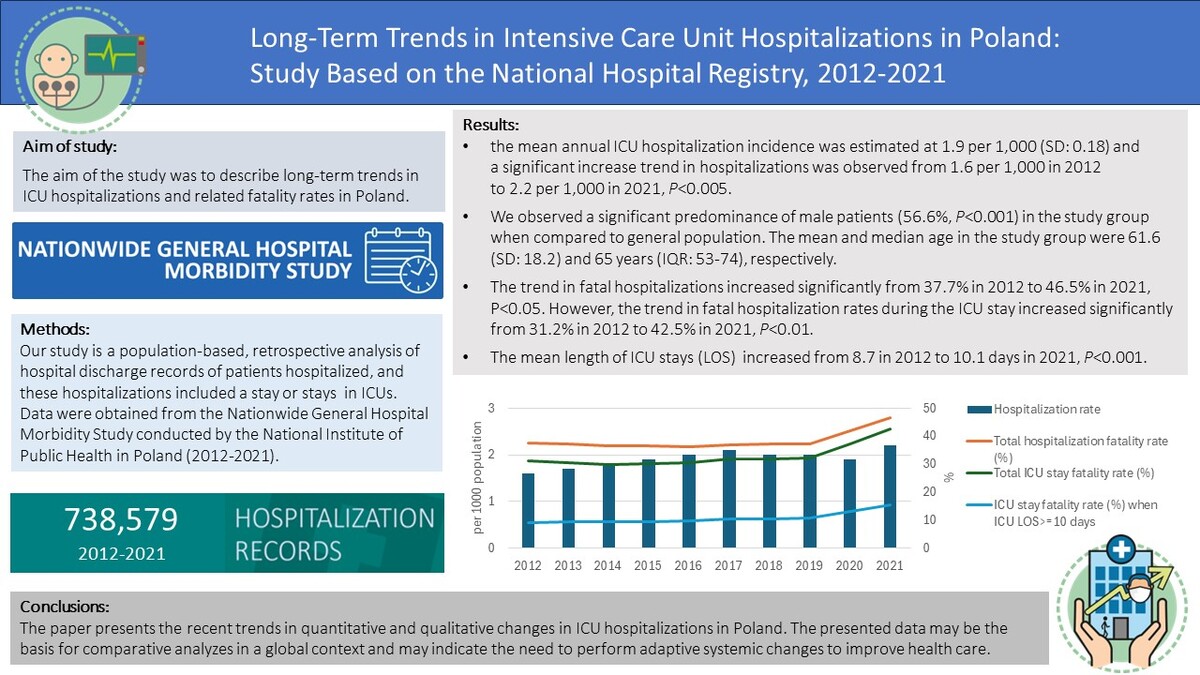

There is limited information on ICU hospitalizations in Poland based on a nationwide database registry [19, 20]. The aim of the study was to describe long-term trends in ICU hospitalizations and related fatality rates in Poland.

Material and methods

Our study is a population-based, retrospective analysis of hospital discharge records of patients hospitalized, and these hospitalizations included a stay or stays in ICUs. Data were obtained from the National Institute of Public Health, National Institute of Hygiene – National Research Institute in Warsaw, and they covered the period from 2012 to 2021. All hospitals in Poland, except psychiatric facilities, are legally required to send discharge data to the institute. The data are anonymous and include information on hospitalizations, dates of admission and discharge, sex, date of birth, and place of residence. The hospital morbidity database used in this study was previously prepared and cleaned by NIZP-PZH (National Institute of Public Health – National Institute of Hygiene) as part of its statutory activities, and no other exclusion criteria were specified in our study. In 11,557 hospitalization records (1.6% of all records), inaccuracies or missing data were noted when reporting the patient’s place of residence. In 971 hospitalization records (0.1% of all records) inaccuracies or missing data were noted when reporting the date of birth or age. The inclusion criterion was a stay in the ICU (department code – 4260) for the entire period or part of the hospitalization. Records were excluded if a patient was hospitalized in the cardiology ICU department (code – 4106). Other studies also separated cardiovascular and medical ICUs [21, 22]. Information on the study presented in this paper was submitted to the local bioethics committee.

To perform most statistical analyses, Statistica (TIBCO Software Inc, version 13) [23] and WINPEPI [24] were used. For continuous variables means, SD, medians and IQR were computed, respectively. For nominal variables, counts, and percentages were analyzed. The data were anonymised, but date of birth, place of residence, and gender were the basis for estimating annual frequencies of hospitalization. Data from Statistics Poland (the national census) were used as denominators [25]. To assess trends, linear regression was used. The trend analysis included the numerical values of events as a dependent variable and the size of a specific population in each year of the study period as an independent variable. In the case of selected variables such as age and length of stay (LOS), a trend analysis in linear regression was performed based on average values calculated for each year in the study period. A two-sided p-value lesser than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Study group

The study was based on 738,579 hospital discharge records of patients hospitalized including stay in ICUs in Poland in 2012–2021. In the analyzed period, one hospitalization was reported in 87.6% of patients, two separate hospitalizations were found in 8.5% of patients, and three hospitalizations were reported in 1.4% of patients. During the study period, one ICU stay during one hospitalization was recorded in 94.5% of cases, and two ICU stays in one hospitalization were observed in 5.2% of hospitalization cases.

Age and sex

In the study group, a significant predominance of male patients was observed: 417,987 (56.6%) males and 320,568 (43,4%) females, p < 0.001, as compared to the sex distribution in the general Polish population. In 24 hospitalization records, sex was not reported as male or female. The mean and median age in the study group was 61.6 years (SD = 18.2) and 65 years (IQR: 53–74 years), respectively. A significant upward trend of mean age was observed during the study period from 60.4 (SD = 18.7) years in 2012 to 62.2 (SD = 17.4) years in 2020 and 61.9 (SD = 16.9) years in 2021, R2 = 0.84, p < 0.001.

Length of stay

The mean and median LOS in hospitalization records were 18.17 and 11 (IQR: 5–22) days, respectively. We did not observe significant changes in the LOS trend during hospitalizations in the study period. The mean and median LOS calculated only for ICU stay were 9.42 (SD = 16.6) and 3 (IQR: 1–11) days, respectively. A significant upward trend of mean length of ICU stay was observed during the study period from 8.7 days in 2012 to 10.1 days in 2021, R2 = 0.92, p < 0.001. During the study period, the maximum hospital stay ranged from 477 days in 2015 to 771 days in 2012, and the maximum ICU stay during hospitalizations ranged from 447 days in 2015 to 670 days in 2012. The overall percentage of patients staying in the ICUs for 10 or more days was 27.8%. LOS was not reported in 303 hospitalization records.

Hospitalization rates and in-hospital fatality rates

Based on the study data, annual information on the number of hospitalizations, percentage of male patients, hospitalization rates, hospitalization fatality rates, overall fatality rates, and ICU-specific fatality rates are presented in Table I. Using data from the hospital registry, the mean annual hospitalization incidence was estimated to be 1.9 per 1,000 hospitalizations (SD = 0.17) and the trend showed a significant increase during the study period from 1.6 per 1000 in 2012 to 2.2 per 1000 in 2021, R2 = 0.67; p < 0.005. During the 2012–2021 period, the mean annual rate of fatal hospitalizations, including the ICU stay, was 38.4% (SD = 3.3). The trend in fatal hospitalizations showed a significant increase from 37.7% in 2012 to 46.5% in 2021, R2 = 0.45, p < 0.05. Similarly, in the years 2012–2021, the mean annual rate of fatal ICU stay was 32.8% (SD = 4.0) The trend in fatal hospitalization rates during the ICU stay showed a significant increase from 31.2% in 2012 to 42.5% in 2021, R2 = 0.59, p < 0.01. In the years 2012–2021, the mean annual rate of fatal ICU stay equal to or longer than 10 days was 10.7% (SD = 2.0). The trend in these fatal hospitalization rates during the ICU stay showed a significant increase from 9.1% in 2012 to 15.4% in 2021, R2 = 0.71, p < 0.005. Hospitalization incidence rates per 1,000 by age range are presented in Table II. In 2021, compared to 2012, an increase in the frequency of hospitalizations was observed in most cases, except for patients aged 0–19 and patients over 80 years of age. Hospitalization fatality rates by age range were presented in Table II. In 2021, compared to 2012, an increase in the frequency of hospitalizations was observed in most cases, except for patients aged 0–14.

Table I

Hospitalizations and fatality rates

Table II

Hospitalization fatality rates (percentage) by age range, 2012–2021

Discussion

Trends in ICU hospitalizations

Based on the hospital registry, the mean annual hospitalization incidence was estimated to be 1.9 per 1,000, and this rate seems to be relatively low in comparison to data from other countries. In a large study from Denmark, the number of ICU patients per 1000 person-years for the 5-year period was 4.3 patients, and it ranged from 3.7 to 5.1 patients per 1000 person-years in the five regions of Denmark, and from 2.8 to 23.1 patients per 1000 person-years in the 98 municipalities [26]. In a study from Korea based on ICU admissions from August 2009 to September 2014, the ICU admission rate was 744.6 per 100,000 person-years (869.5 per 100,000 person-years in men and 622.0 per 100,000 person-years in women) [27]. A significant predominance of male patients was also observed in our study, as presented in Table I. In another study on 1425 patients, 780 (54.7%) were male [28].

The study presented in this paper showed a statistically significant upward trend in the frequency of hospitalizations, as presented in Table I. The growing trend in hospitalizations may result both from the organization of health care and the aging of the Polish population [29]. The elderly were the main groups hospitalized in ICUs, as reported in Table III. This may result both from the organization of health care and multi-morbidity among the elderly, which increases with age and increases the health needs of this group of patients. Hospitalization incidence rates per 1,000 by age range are presented in Table III. In 2021, compared to 2012, an increase in the frequency of hospitalizations was observed in most cases, except for patients aged 0–19 and patients aged 80 years and over. In a study from Texas, United States, which was based on ICU hospitalizations of patients with dementia aged 65 years or older, increasing comorbidity burden, rising severity of illnesses, and increasing use of health care resources were reported [30].

Table III

Hospitalization incidence rates per 1000 by age range, 2012–2021

The mean age in our study was relatively high, at 61.6 years, and the trend of mean age was significantly increasing during the study period. Additionally, as shown in Table I, in each year during the study period, male predominance was observed in the study group and among the total number of deaths, as well as deaths during the stay in the ICU. Data from another study on a large group of 223,129 patients admitted to ICUs in Australia and New Zealand showed a lower mean age of 59.2 years and 41.7% of female patients [31]. Older age and male sex were also reported to be risk factors for ICU admission and death. In a recent meta-analysis of 59 studies when hospitalized with COVID-19, men more often developed severe COVID-19 disease and more often required intensive care admission, ultimately resulting in death more often. Additionally, in this study it was reported that patients aged 70 years and above affected by COVID-19 were more likely to require ICU admission and experience in-hospital mortality compared with patients younger than 70 years [32].

In another meta-analysis based on 229 studies including over 10 million patients, it was reported that men had a higher risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, disease severity, ICU admission, and death [33].

In our study, the mean LOS was on a stable level, with small fluctuations when analyzing the length of hospitalization stay. However, the mean ICU stay was increasing. The mean LOS seems to be long when compared to data from other countries. In one study on healthcare-associated infections in ICUs, the observed LOS was 11.66 days [34]. In another study on 108,302 ICU patients, the reported LOS was 9 days [8]. Yet another study from Australia and New Zealand showed the ICU LOS of 3.6 days [31]. Another study revealed the median ICU and hospital length of stay of 4 and 13 days, respectively [27]. Long ICU stay I associated with a significant financial burden. However, premature discharges appear to have a significant impact on mortality in the hospital care of critically ill patients [35].

In our study, the average percentage of patients staying in ICUs for 10 days or more was 27.8%, which may be relatively high. In another study, patients staying in the ICU for 10 days or more accounted for only 5% of all ICU patients. It was also highlighted that these patients’ outcomes were markedly worse than the outcomes of patients staying in the ICU for less than 10 days [36]. LOS plays an important role not only in patients’ outcomes. It should be highlighted that the economic burden of ICU-acquired pneumonia may be mainly related to an increased length of stay of surgical patients and patients with mid-range severity scores at admission [37].

In our study, during one hospitalization, one stay in the ICU was recorded in 94.5% of cases, and this may be related to the long ICU stay observed in our study. In the analyzed 10-year period of the study, not more than one hospitalization with ICU stay was found in 87.6% of patients, which can be considered a satisfactory result. It was reported that readmission to the ICU was associated with poor clinical outcomes, increased length of ICU and hospital stay, and increased costs. In one study based on data of 5,779 patients admitted to the ICU, 10% of patients were readmitted to the ICU during the same hospitalization [10]. In another study, in a year after the ICU care, 10% were readmitted to the ICU [5].

Trends in in-hospital and ICU mortality

The study revealed a relatively high percentage of fatality for all hospitalizations and ICU stays, with predominance of male patients, as reported in Table I. In another study, the hospital mortality rate among patients admitted to ICUs was 19.0% [5]. In this study, women showed a significantly higher hospital mortality than men, which is opposite to the results obtained in our study. Furthermore, the mean and median ICU length of stay in this study were relatively low in comparison to our study, at 3.96 and 2.33 days, respectively. In a study from Korea, the overall in-hospital mortality was 13.8%. Among all Koreans, the ICU mortality rate was 102.9 per 100,000 person-years (122.5 per 100,000 person-years in men and 83.8 per 100,000 person years in women) [27]. In a recent study based on data of 500,124 patients admitted to ICUs, 420,187 (84%) persons survived to hospital discharge [38]. In another study, the overall mortality rate was reported to be 37.6%, and it was associated with the age of over 75 years, transfer from a medical ward, a communicable disease, and cardiovascular disease [28]. In yet another study, mortality among ICU patients was reported to be 18.5% [8].

Trends in fatal hospitalizations and ICU-specific fatal hospitalizations showed significant increases in the study period, with more marked increases in 2020 and 2021, which may be related to the COVID-19 pandemic. In a recent meta-analysis, almost half of patients with COVID-19 receiving invasive mechanical ventilation died according to the reported case fatality rates (CFR), but the authors of the study reported that variable CFR reporting methods resulted in a wide range of CFRs across studies [39]. In another systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled CFR of COVID-19 in hospitalized patients was 13.0%, and the pooled CFR in patients admitted to ICUs was 37.0% [40]. Additionally, it may be supposed that many patients with COVID-19 required care in the ICU after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in Poland. In a retrospective cohort study of critically ill patients admitted to ICUs in Lombardy, Italy, with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, the mortality rate and absolute mortality were high [41]. A precise explanation of the increase in mortality in the study group in Poland in 2020–2021 may require further focused research including comorbidity analyses.

Tables II and III showed that hospitalization incidence rates and hospitalization fatality rates increased with age, with the highest fatality observed in the elderly. In comparison, the mean annual number of hospitalizations involving an ICU admission in a study covering hospitalizations of patients aged ≥ 65 years in New York City hospitals in 2000–2014 decreased from 57,938 during 2000–2002 to 45,785 during 2012–2014. The proportion of hospitalizations involving an ICU admission in which in-hospital death occurred decreased from 15.9% during 2000–2002 to 14.5% during 2012–2014 [42]. In a study analyzing the outcomes of very elderly patients (85 years old or older), the mortality rate was 81.7% and the rate of survival in intensive care units was low [43].

It is worth mentioning that in our study, hospitalization fatality rates among children aged 0–14 years were observed to decrease in 2021 in comparison to 2012, as presented in Table II. In a study from Korea, the overall mortality of critically ill children was 4.4%, with a significant decrease in mortality from 5.5% in 2012 to 4.1% in 2018 (p for trend < 0.001); however, neonates and neonatal ICU admissions were excluded in the abovementioned study [44].

Despite the fact that overall ICU fatality rates were reported to be high, the mortality rate in the subgroups of ICU patients with LOS ≥ 10 days was noticeably lower in comparison to total ICU stay fatality rates, as reported in Table I. This suggests that the initial condition of patients admitted to ICUs may be responsible for the high mortality rate among ICU patients.

Advantages and limitations of the study

The study used data from the national hospital morbidity register, which was not analyzed in terms of the reliability and consistency of the reported data. However, the legal obligation to report hospitalization data to the register, as well as legal regulations on data processing in relation to official statistics, may suggest high reliability and consistency of the data used. A comparison of our results with other studies and other health systems in the world is very difficult. Differences may result from many factors, such as healthcare organization, financing methods, admission criteria, training of doctors and nurses, and cultural and ethical differences.

Conclusions

The paper presents the latest trends in quantitative and qualitative changes in hospitalizations in non-cardiac ICUs. Among the observed trends, the growing trend of ICU hospitalizations and the trend of hospital deaths in ICUs should be given special attention. The presented data may be an important source for further analysis of changes in ICU hospitalization, and a basis for comparative analyses in a global context. Furthermore, they may indicate the need to perform adaptive systemic changes to improve health care in Poland.