Introduction

Mobile social media is a new type of online media that is participatory, open, and communicative, among other characteristics [1]. Due to the increasing popularity of social media, this technology has become an indispensable part of people’s social lives. According to a survey, the usage rate of WeChat’s circle of friends in China alone has reached 85.1% [2]. However, due to the continuous development of diverse social media functions, the negative consequences of this technology have also aroused social concern. College students must use social media for studying, work, information searches, entertainment, and leisure, and the use of apps such as WeChat, QQ, Weibo, and Moments has become a daily routine for such students [1]. This situation has greatly increased the usage time and stickiness of social media, resulting in social media addiction, a social psychological phenomenon in which an individual loses control over their usage time and intensity, leading to psychological and physiological discomfort [3]. An increasing number of researchers are paying attention to social media addiction [4, 5], and studies have shown that college students are a high-risk group for social media addiction [6], which is related to a series of negative consequences, such as low life satisfaction, poor academic performance, and sleep disorders [7, 8]. However, fewer studies have focused on social media addiction in relation to an individual’s upbringing in terms of childhood psychological abuse and left-behind experiences, and there is a relative research gap with regard to examining the relationships of and roles played by social media addiction in this respect. Therefore, to mitigate the adverse effects of social media addiction and develop effective prevention and remediation programs, this paper explores the factors influencing social media addiction with the goal of promoting the healthy growth and development of college students.

Childhood psychological abuse and social media addiction

Childhood psychological abuse refers to a situation in which parents or caregivers fail to meet a child’s needs for love, support, a sense of belonging and care [9]. According to attachment theory, having a good relationship with one’s parents provides a sense of security and belonging [10]. In contrast, emotional neglect in childhood represents a negative mode of interaction in parent‒child relationships, which makes it difficult for individuals to meet their emotional needs consistently [10]. To alleviate negative emotions, obtain emotional support, and seek stable intimate relationships, people turn to the internet and other social media [11]. Thus, individuals with a history of psychological abuse are more likely to continue to access social media [12, 13]. A great deal of research has confirmed that childhood psychological abuse has adverse effects on an individual’s short- and long-term development, including emotional dysregulation, health problems, and problem behaviors [14, 15], and represents a key risk factor for social media addiction. Therefore, childhood psychological abuse can directly predict college students’ propensity toward social media addiction [16, 17]. Accordingly, the first hypothesis of this study proposes that childhood psychological abuse is positively correlated with social media addiction among college students [18].

Hypothesis 1: Childhood psychological abuse is positively associated with social media addiction among college students.

The mediating role of fear of missing out

Fear of missing out (FOMO) refers to diffuse anxiety that arises from concerns with missing out on others’ novel experiences or positive events [19]. This emotional state is caused by specific environments or experiences, and the corresponding external behavior takes the form of frequent participation in social activities or frequent checking of social media [20]. Przybylski et al. defined fear of missing out as a diffuse type of anxiety that occurs when an individual is worried about missing out on the wonderful experiences and rewards obtained by others. Externally, fear of missing out takes the forms of not wanting to miss out on meetings with friends in offline contexts or frequently logging on to social media and refreshing the content of social networking sites in online contexts; internally, it takes the form of a constant desire to learn about what others are doing [19]. Higher levels of fear of missing out can lead individuals to become addicted to social media and develop some nonadaptive problematic behaviors.

According to the individual-emotion-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model of internet use disorder, there are close links between the environment or stimulus in which a person finds themselves and their emotional response, cognitive level, and execution behavior [21]. Children who have experienced psychological abuse lack stable relationships and desire to be able to track what others are experiencing in real time [22]. Such children are very worried about missing something important and thus remain in a state of anxiety, which makes them more susceptible to FOMO. Individuals with FOMO fear that they will miss out on important information and events and often rely on social media to keep track of important information such as friends’ activity trajectories and group activities, which can lead to a sense of satisfaction and eventually result in social media addiction [3]. Therefore, we can argue that childhood psychological abuse and neglect contribute to the development of negative emotional problems, that fear of missing out has a stronger effect in this context [23], and that childhood psychological abuse positively contributes to individuals’ fear of missing out. Meanwhile, individuals with a high level of fear of missing out exhibit lower interpersonal security and less pro-social behavior [24] and are more likely to develop social media addiction [25]; in addition, fear of missing out has a positive effect on social media addiction. The fear of missing out thus plays a mediating role in the effect of childhood psychological abuse on social media addiction. Therefore, the second hypothesis of this study is that FOMO plays a mediating role in the relationship between childhood psychological abuse and social media addiction among college students.

Hypothesis 2: Fear of missing out mediates the relationship between childhood psychological abuse and social media addiction among college students.

The moderating role of the presence or absence of left-behind experiences

Left-behind children are a social issues that has received attention. Does left-behind experience play a regulating role in the effects of childhood psychological abuse on missed anxiety and social media addiction? On the one hand, compared with adolescents who have not experienced being left behind, adolescents with such experience exhibit higher rates of internet addiction [26]. Conservation of resources (COR) theory posits that people seek to obtain, retain, and protect resources and that stress occurs when those resources are threatened with loss or lost or when individuals fail to gain resources after substantive resource investments. According to COR theory, the more resources an individual has, the better he or she is able to adapt, and when resources are insufficient, a variety of adaptive stress problems arise [27]. Parents are the most important resource providers for adolescents. When parents leave, there is a lack of direct interaction between parents and children; parents have fewer chances to offer help, guidance, encouragement and affirmation to their children, and the psychological resources available to the children are reduced [28]. Individuals who do not have left-behind experiences and grow up in sound family environments are more likely to obtain parental resources to increase their sense of security and fulfilment and reduce their anxiety, and individuals with low anxiety are less likely to need to satisfy their intrinsic self-needs through social media. In contrast, individuals who have left-behind experiences and grow up in unsound family environments have difficulty obtaining parental care and resources, which may cause such children and adolescents to experience more loneliness, anxiety and other negative emotions. To alleviate such negative emotions, adolescents often choose to retrieve their lost sense of satisfaction through an illusory online world. On the other hand, some studies have expressed different views, stating that left-behind children do not engage in more deviant behavior [29]. According to the person-environment interaction theory, individual characteristics (personality, self, cognition, emotion, and behavior) and environmental characteristics (school, family, and peers) all affect internet addiction [30]. Not all children who have been left behind exhibit addictive behavior. If left-behind children experience psychological abuse, this experience can help them develop a positive understanding of adversity, discover the true meaning of life, reduce anxiety, and make them more self-reliant and focused on self-improvement, thereby reducing their risk of social media addiction [31].

Hypothesis 3: The presence or absence of left-behind experiences moderates the direct path and the first half of the mediating effect proposed in Hypothesis 2.

Material and methods

Participants and procedure

As this was the period when COVID-19 was popular in the country, we conducted a convenience-sampling questionnaire survey. We selected some college students at three universities as survey subjects. These students voluntarily participated in the questionnaire survey. The three universities are all located in the central province of Hubei in China; one university is a public key university focused on finance and economics, one is a public undergraduate university focused on science and technology, and one is a private higher vocational college focused on art. The three universities represent different levels and types of college students. The questionnaire was administered in a way that took into account both the relevant authority and the number of questions. The questionnaire was distributed via Questionnaire Star, and a total of 1928 responses were received. After excluding invalid questionnaires that featured short answer times or regular answers, a total of 1694 valid questionnaires were recovered. Of the respondents, 677 were male students, and 1017 were female students. The sample included 266 4th-year students (15.7%), 344 3rd-year students (20.3%), 381 2nd-year students (22.5%), and 703 1st-year students (41.5%). A total of 695 respondents had left-behind experiences, while 999 had no left-behind experiences. The investigation was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Wuhan Polytechnic University under approval number BME-2023-1-03.

Tools

Childhood Psychological Abuse Scale

The Childhood Psychological Abuse Scale (CPAS) was developed by Yunlong Deng et al. (2007) [32] to investigate psychological abuse in childhood among individuals and is a retrospective measurement tool. The scale consists of 14 questions divided into three dimensions: scolding, intimidation, and interference. This measure is scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (none) to 4 (always), e.g., “Parents often compare me with others and always say that I’m useless”, “Parents don’t like me having contact with classmates after class”, “Parents become furious with me.” Higher scores indicate more psychological abuse in childhood. The internal consistency reliability of this questionnaire in this study was 0.94. The fit indices for this scale in this study were χ2/df = 2.25, CFI = 0.97, and RMSEA = 0.04, thus indicating acceptable construct validity.

Fear of Missing Out Scale

The Fear of Missing Out Scale developed by Przybylski et al. is the most widely used instrument for measuring fear of missing out [19]. As defined by Przybylski et al., FOMO refers to diffuse anxiety caused by the fear of missing out on other people’s wonderful experiences and rewards. The scale encompasses both online and offline situations and measures an individual’s overall level of fear of missing out. The scale consists of 8 questions and is scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), e.g., “I am afraid that others have more exciting experiences or gains than me”, “I feel anxious when I don’t know what my friends are doing”, and “When traveling, I still pay close attention to my friends’ latest developments”. Higher scores on the scale indicate higher anxiety regarding missing out. The internal consistency reliability of this questionnaire in this study was 0.86, and the fit indices for this scale in this study were χ2/df = 1.76, CFI = 0.98, and RMSEA = 0.04, thus indicating acceptable construct validity.

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale

The Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale was developed by Andreassen and Pallesen (2016) [33]. This scale consists of six dimensions – salience, tolerance, conflict, relapse, withdrawal, and emotion regulation – and it is currently the most widely used social media addiction measurement tool. The scale consists of 18 questions scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), such as “Spend a lot of time thinking about social media or planning to use social media”, “Feel an increasing impulse to use social media”, and “Use social media to reduce feelings of guilt, anxiety, helplessness and frustration”. The higher the score on the scale is, the stronger is the social media addiction. The internal consistency reliability of this questionnaire in this study was 0.91. The fit indices of this scale in this study were χ2/df = 2.87, CFI = 0.95, and RMSEA = 0.05, thus indicating acceptable construct validity.

Data analysis strategy

SPSS 21.0 software was used to perform descriptive statistical analysis and correlation analysis on the collected data. Amos 22.0 software was used to validate the factor analysis. Accordingly, the theoretical hypothesis model was further tested by estimating the 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect based on 5000 samples using Model 4 and Model 8 in the SPSS macro program PROCESS. The results showed that 95% of the confidence intervals (CIs) did not include zero, thus indicating statistically significant mediating or moderating effects [34].

Results

Common Method Bias Test

The Harman single-factor test was used to test for common method bias. The results showed that 24 factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, and the first factor explained only 30.24% of the variance, which was lower than the critical standard of 40%, thus indicating the absence of serious common method bias in this study.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses

The mean scores for childhood psychological abuse, missed anxiety, and social media addiction were used for correlation analyses. The results showed that social media addiction was significantly positively correlated with childhood psychological abuse and missed anxiety and that childhood psychological abuse was significantly positively correlated with missed anxiety. The specific results are shown in Table I.

Mediation analysis of fear of missing out

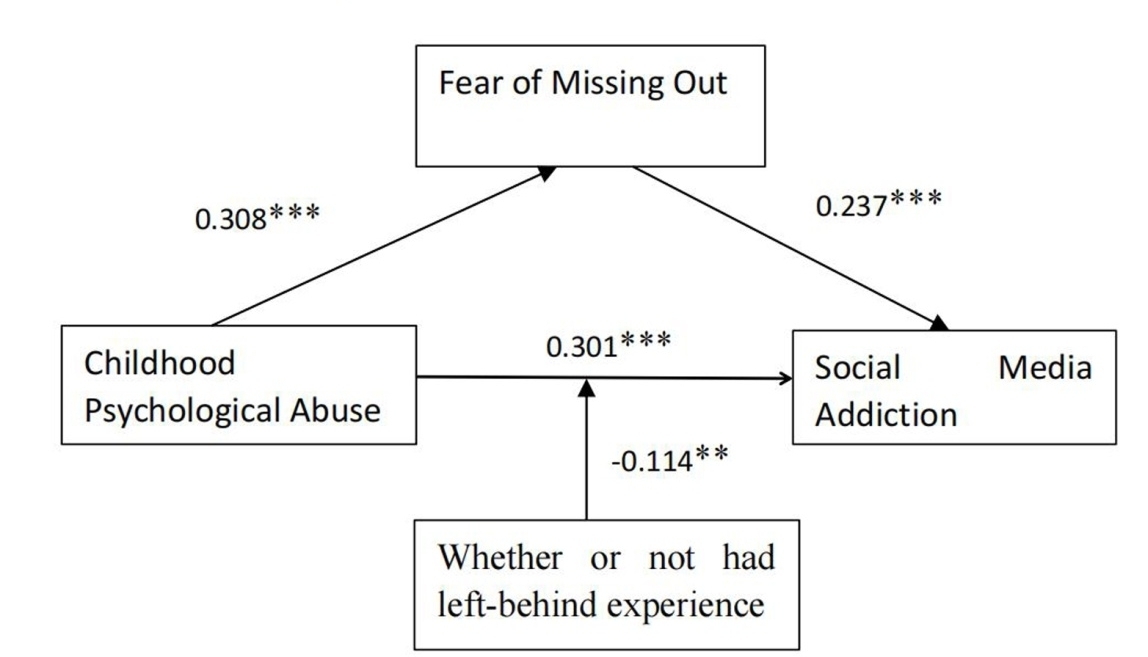

The mediating role of fear of missing out in the relationship between childhood psychological abuse and social media addiction was analyzed while controlling for gender. Childhood psychological abuse had significant predictive effects on social media addiction (β = 0.317, p < 0.001) and missed anxiety (β = 0.308, p < 0.001). When childhood psychological abuse and missed anxiety were both used to predict social media addiction, childhood psychological abuse remained a significant predictor (β = 0.243, p < 0.001), as did missed anxiety (β = 0.239, p < 0.001). The specific results are shown in Table II.

Table II

Regression analysis of the relationship between variables in the model

| Regression equation | Overall fit index | Regression coefficient significance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | Predictor variable | R | R2 | F | β | Bootstrap Lower bound | Bootstrap Upper bound | t |

| SMA | Gender | 0.33 | 0.109 | 103.123 | –0.196 | –0.266 | –0.125 | –5.457*** |

| CPA | 0.317 | 0.271 | 0.363 | 13.603*** | ||||

| FoMO | Gender | 0.265 | 0.07 | 63.985 | –0.296 | –0.39 | –0.201 | –6.147*** |

| CPA | 0.308 | 0.247 | 0.37 | 9.867*** | ||||

| SMA | Gender | 0.448 | 0.2 | 141.138 | –0.125 | –0.192 | –0.058 | –3.639*** |

| CPA | 0.243 | 0.199 | 0.288 | 10.714*** | ||||

| FoMO | 0.239 | 0.205 | 0.273 | 13.916*** | ||||

The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap test was further used to examine this mediating effect. The 95% confidence interval for the direct effect did not include zero, thus indicating a significant direct effect. The paths featuring missed anxiety as a mediator did not include zero, thus indicating that missed anxiety played a mediating role in the relationship between childhood psychological abuse and social media addiction (Table III).

Moderation test of left-behind experience

With regard to personal information, “Have your parents or one of them ever worked away from home for more than half a year, leaving you behind in your registered residence without living together with your parents?” was given a score of 1 for left-behind experience and 0 for no left-behind experience [35].

The moderating effect of left-behind experience was tested in the first half of the model, as shown in Table IV. The interaction between childhood psychological abuse and left-behind experience had a negative moderating effect on missed anxiety (β = –0.135, t = –2.135, p < 0.05), thus indicating that the effect of childhood psychological abuse on missed anxiety was influenced by left-behind experience. In other words, among college students with left-behind experience, higher levels of childhood psychological abuse were significantly associated with an increase in missed anxiety (β = 0.221, t = 4.711, p < 0.001). Conversely, among college students without left-behind experience, higher levels of childhood psychological abuse were even more significantly associated with an increase in missed anxiety (β = 0.361, t = 8.367, p < 0.001).

Table IV

Tests for moderating effects of the first half of the pathway

| Variable | FoMO | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | 95% CI | R2 | F | ||

| Gender | –0.294 | 0.048 | –6.127*** | –0.389 | –0.2 | 0.073 | 33.195 |

| CPA | 0.371 | 0.043 | 8.691*** | 0.276 | 0.445 | ||

| Whether or not had left–behind experience | 0.252 | 0.132 | 1.904* | 0.003 | 0.526 | ||

| CPA* Whether or not had left–behind experience | –0.135 | 0.063 | –2.135* | –0.264 | –0.014 | ||

The moderating effect of left-behind experience on the direct path was also tested, as shown in Table V. The interaction between childhood psychological abuse and left-behind experience had a negative moderating effect on social media addiction (β = –0.114, t = –2.552, p < 0.01), thus indicating that the direct effect of childhood psychological abuse on social media addiction was influenced by left-behind experience. Similarly, among college students with left-behind experience, higher levels of childhood psychological abuse were significantly associated with an increase in social media addiction (β = 0.179, t = 5.421, p < 0.001), while among college students without left-behind experience, higher levels of childhood psychological abuse were even more significantly associated with an increase in social media addiction (β = 0.294, t = 9.539, p < 0.001).

Table V

Tests for moderating effects of direct path

| Variables | SMA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | 95% CI | R2 | F | ||

| Gender | –0.125 | 0.034 | –3.662*** | –0.193 | –0.058 | 0.205 | 87.213 |

| CPA | 0.301 | 0.031 | 9.803*** | 0.241 | 0.362 | ||

| FoMO | 0.237 | 0.017 | 13.789*** | 0.203 | 0.27 | ||

| Whether or not had left-behind experience | 0.154 | 0.093 | 1.749* | 0.002 | 0.337 | ||

| CPA*Whether or not had left-behind experience | –0.114 | 0.045 | –2.552** | –0.201 | –0.026 | ||

Discussion

Previous studies have found that childhood psychological abuse positively predicts social media addiction among college students [10]; however, the mechanisms underlying this impact have not been clearly revealed. The results of this study indicate that childhood psychological abuse directly predicts social media addiction and that missed anxiety plays a partial mediating role in this context; simultaneously, the presence of left-behind experience plays a moderating role in the first half of the mediating effect and in the direct effect. The results support Hypothesis 1, which posited that childhood psychological abuse and social media addiction exhibit a positive relationship; this finding is consistent with the results of previous research [36]. In the model with missed anxiety as the mediator, childhood psychological abuse still positively predicts social media addiction. Emotional neglect and abuse during childhood have profound effects on college students’ problem behavior and are more likely to lead to social media addiction [37]. Individuals with high levels of childhood psychological abuse often suffer from the pressure of resource loss during their growth process and thereby unconsciously seek support from others in their networks and look for ways of overcoming difficulties, thereby gradually developing a dependence on social media and easily forming social media addiction. In contrast, individuals who did not experience psychological abuse during childhood have supportive family members, parents, teachers, and classmates, which enables them to establish stable relationships and exhibit confident performance during social interactions, thus leading to low levels of missed anxiety. Therefore, although such individuals also use social media, they manage their time and life reasonably and are not prone to social media addiction.

The results support Hypothesis 2, which posited that missed anxiety in college students plays a mediating role in the relationship between childhood psychological abuse and social media addiction, which is consistent with the results of previous research [37]. The higher the level of childhood psychological abuse is, the less effective information individuals can obtain, and the more worried they are about missing information from friends and important people around them; this situation results in an increase in the time and frequency with which they seek resources on the internet to meet their needs in a timely manner. Therefore, such individuals are prone to develop social media addiction. In contrast, individuals who did not experience psychological abuse during childhood received support and help from others such as family, parents, teachers, and classmates during their growth process, thus enabling them to establish stable relationships and exhibit confidence during social interactions, leading to low levels of missed anxiety; furthermore, although they also use social media, they manage themselves and their lives reasonably and are not prone to developing social media addiction.

The results support Hypothesis 3, which posited that whether an individual has a left-behind experience plays a moderating role in the first half of the mediating effect of missed anxiety on the relationship between childhood psychological abuse and social media addiction among college students. Specifically, the impact of childhood psychological abuse on missed anxiety was impacted by the presence of left-behind experience, and the missed anxiety of college students with left-behind experience was associated with a more significant upward trend than that of those without left-behind experience. With regard to the direct path, the impact of childhood psychological abuse on social media addiction was also impacted by the presence of left-behind experience, and the social media addiction of college students with left-behind experience was associated with a more significant upward trend than that of those without left-behind experience. Left-behind experiences to some extent enhance the optimism and self-efficacy of left-behind children, who actively seek value and meaning in adversity and view adversity as a driving force for personal development rather than escaping reality and indulging in the virtual world [29], which is not conducive to the development of social media addiction.

In summary, this study explored the relationship between childhood psychological abuse and social media addiction, the mediating role of missed anxiety, and the moderating role of left-behind experience. This study thus not only enriches the research on the relationship between childhood psychological abuse and social media addiction among college students but also explores the internal mechanism underlying this relationship.

The results of this study suggest that universities and families should pay attention to the psychological health of children, especially with regard to the living conditions of left-behind children and those who experience psychological abuse; in addition, universities and families should provide care and guidance to such children in a timely manner. First, parents can be made aware of the adverse effects of traumatic childhood experiences on their children’s future development through parenting schools and community-based learning to enable them to pay attention to their children’s early parenting, improve their parenting skills, adopt a positive parenting style toward their children, and establish a close family atmosphere to prevent the occurrence of addictive behaviors in adolescents. Second, teachers can also apply the concept of human-centered education, pay attention to students’ thoughts, and help students find a suitable direction for their own development with the goal of effectively alleviating students’ anxiety. For students who experience more negative emotions, schools can enhance their social skills, such as those pertaining to listening, communication and praise, through relevant mental health education activities, and they can encourage young people to open up and integrate positively into the community through interaction and classroom activities. Again, psychological interventions are beginning to play an important role in treatment [38], and schools and societies can help by providing further psychological counseling and treatment services for college students, using emerging technologies such as VR to alleviate students’ feelings of stress and anxiety [39], as well as encouraging them to use social media in a healthy, moderate, and sensible way. Likewise, we hope that our findings can help educational institutions design social media addiction mitigation programs that are suitable for the university student population and can improve their physical and mental health and quality of life.

This study also has some limitations and shortcomings, such as the need for accurate tracking and investigation to reveal the relationships among childhood psychological abuse, coping methods, and social media addiction among college students; tracking research is lacking in this study.