Introduction

Cruciate ligament rupture is a common injury involving the knee joint. Among these injuries, anterior cruciate ligament rupture accounts for a high proportion, while the incidence of posterior cruciate ligament is relatively low. Therefore, there are relatively few studies on the diagnosis and treatment of posterior cruciate ligament rupture. As the posterior cruciate ligament is an important structure in maintaining the stability of the rear of the knee joint, there is a high demand for its diagnosis and treatment. Surgical treatment is an effective method for cruciate ligament rupture. The effects of different surgical methods vary significantly, and their impact on joint stability also varies [1, 2]. Recently, there have been an increasing number of clinical studies using single-bundle autologous hamstring tendon reconstruction to treat this type of injury, and most studies have strongly supported its effectiveness. However, research also generally shows that its early treatment effect on posterior cruciate ligament is better and its stability is acceptable, but as time goes by, its stability is affected. Therefore, finding a treatment method that can effectively control graft stability has become the focus of clinical research [3–5]. As a non-absorbable suture that is increasingly applied in orthopedic procedures, braided sutures have obvious advantages in terms of tissue compatibility and strength. However, there are relatively few studies on its application in patients with posterior cruciate ligament autologous hamstring tendon single-bundle reconstruction, including a dearth of research on the impact on patients’ joint stability. Therefore, this study now explores the effect of autologous hamstring tendon single-bundle reconstruction combined with braided threads on the joint stability and clinical efficacy of patients with posterior cruciate ligament rupture to provide a reference for the selection and formulation of treatment methods for patients with this type of surgery. The objective of this study was to examine the effects of autologous hamstring tendon single-bundle restoration in combination with braided threads on both joint stability and clinical efficacy in patients with posterior cruciate ligament rupture.

Material and methods

General data

Based on the preliminary experiment and the calculation formula, the number of participants in this trial was determined to be 106. Therefore, 106 patients with posterior cruciate ligament rupture during the period from December 2020 to June 2022 were divided into a control group of 53 cases and an observation group of 53 cases according to the random number table approach. Inclusion criteria: patients aged 20–65 years; patients with posterior cruciate ligament rupture confirmed by the drawer test and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); patients who meet the indications for surgery; patients who signed the informed consent form for this study. Exclusion criteria: patients with other ligament injuries, degenerative disease, history of knee joint surgery; bilateral injuries; chronic diseases; pregnancy and lactation were excluded from this study.

Treatment methods

The control group underwent autologous hamstring tendon single-bundle reconstruction treatment. Combined epidural anesthesia was performed with the double Endo-Button technique after routine preoperative examination, as follows: Routinely establish an anterior medial and lateral approach to the knee, insert an arthroscope, and conduct detailed exploration of the lesion and surrounding conditions; those with meniscal injuries should be repaired first. Take the patient’s autogenous hamstring tendon, braid and suture both ends of the tendon, and fold it into four strands (each with a diameter of 9 mm). Establish tibial and femoral channels, paying attention to the location of the channels. The tibial tunnel uses a reverse drill to drill a bone channel of appropriate length. Then the tendon is first introduced into the femoral channel under the guidance of the steel wire. Then guide the other end of the tendon into the tibial tunnel under the guidance of the wire. With the knee extended, the tendons are effectively tightened.

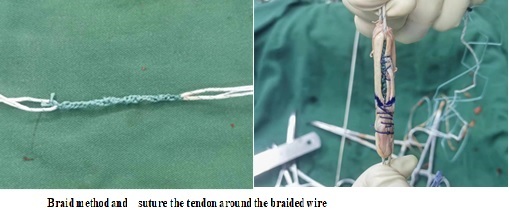

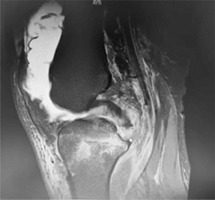

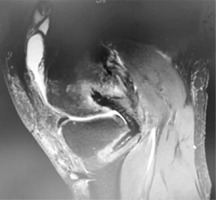

The study group underwent autologous hamstring tendon single-bundle reconstruction combined with braided thread treatment. It adopts double Endo-Button technology and uses Ethicon thread to knit with a flat knot (Figure 1). The technique is as follows: Braid to the desired length, wrap and suture the tendon around the braided wire (the total diameter of the graft is 9 mm) (Figure 2). MRI taken intraoperatively as well as pre- and postoperatively are shown in Figures 3–5.

Postoperative rehabilitation

During the first week after the operation, the focus is on isometric contractions of the quadriceps femoris, with small-range active flexion and extension activities within the painless range. Beginning in the second week, patients may get out of bed wearing a brace and ambulate with partial weight-bearing using crutches. During the non-weight-bearing period, joint flexion and extension exercises are progressively intensified until the full range of motion is restored, accompanied by continued muscle-strengthening training. The brace and crutches are typically discontinued 3 months after surgery, at which point normal walking is permitted. Low- to moderate-intensity physical activities can be gradually resumed 6 to 7 months postoperatively.

Observation indicators

We assessed the comparative rates of successful and satisfactory outcomes in treatment, the occurrence of complications, indicators of joint activity both pre- and postoperatively (including range of motion and maximum flexion), parameters related to walking (such as stride length, walking speed, and gait asymmetry index), knee joint function (Rasmussen score), and joint stability (as determined by the results of the KT2000 test). (1) Effect of treatment: The patients’ treatment effects were assessed based on the knee joint function scoring criteria. The evaluation consists of six positive aspects and one negative aspect, with a total score of 100 points. Scores of ≥ 85, 70–84, 60–69, and ≤ 59 correspond to excellent, good, average, and bad performance, respectively [6]. The treatment satisfaction rate was computed. (2) Complication incidence rate: The occurrence rates of complications, including infection, vascular and nerve injury, and flexion limitation, were computed for both groups. (3) Joint activity index: The joint activity of both groups was assessed prior to surgery and 12 months after surgery, measuring the range of motion and maximum flexion of the knee joint. These specific indicators were determined using plain radiograph assessment. (4) Gait parameters: A three-dimensional gait analysis system was used to identify and examine the gait characteristics of both patient groups before surgery and 12 months postoperatively. These parameters included stride length, walking speed, and gait asymmetry index. (5) Knee function: The knee joint function of the two groups was evaluated according to the Rasmussen score before surgery and 12 months after surgery. It includes five aspects of assessment: pain, walking ability, knee extension, joint mobility, and joint stability. The maximum score for each aspect is 6 points – the higher the score, the better the functional status of the knee joint. (6) Joint stability index: The KT2000 arthrometer was used to detect the tibial posterior translation of the two groups at 15 pounds, 20 pounds, and 30 pounds before surgery and 12 months after surgery, including forward and rear displacement; the average value was measured three times [7].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the program SPSS 23.0. Count data were expressed as n (%). The χ2 test was employed to make comparisons between the groups. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). Group comparisons were conducted using independent sample t-tests. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of data of two groups

The two groups did not demonstrate any significant differences in terms of gender, age, BMI value, course of disease, lesion site, and cause of injury (p > 0.05) (Table I).

Table I

Comparison of general data of the two groups

Comparison of overall treatment of two groups

The treatment rate in the study group was significantly higher than that in the control group, as indicated by the statistical analysis (p < 0.05) presented in Table II.

Comparison of complication rates of the two groups

There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of complications between the two groups (p > 0.05); see Table III.

Comparison of joint activity indicators of the two groups before and after surgery

The preoperative difference in joint activity indices between the two groups was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). However, 12 months following surgery, the study group exhibited significantly higher joint activity index values compared to the control group (p < 0.05) (Table IV).

Table IV

Comparison of joint activity indicators before and after surgery between the two groups

Comparison of gait parameters of two groups before and after surgery

When analyzing the gait metrics of the two groups before surgery, no statistically significant difference was detected (p > 0.05). After 12 months of surgery, the study group had substantially higher values for both stride length and walking speed, compared to the control group. Furthermore, the study group had a significantly decreased gait asymmetry index compared to the control group. The control group exhibited a statistically significant difference at a significance level of p < 0.05, as indicated in Table V.

Table V

Comparison of gait parameters between the two groups before and after surgery

Comparison of Rasmussen scores between the two groups before and after surgery

The difference in Rasmussen scores between the two groups before surgery was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The Rasmussen score of the study group 12 months after surgery was markedly higher compared to the control group, and this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). See Table VI.

Table VI

Comparison of Rasmussen scores between the two groups before and after surgery [points]

Table VII

Comparison of forward displacement between the two groups before and after surgery [mm]

Table VIII

Comparison of posterior displacement between the two groups before and after surgery [mm]

Comparison of KT2000 test results between the two groups before and after surgery

The comparison of the KT2000 test results between the two groups before surgery did not show a statistically significant difference (p > 0.05). The KT2000 test results of the study group 12 months after surgery were markedly lower compared to the control group, and this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Refer to Tables VII and VIII.

Discussion

Posterior cruciate ligament rupture can cause local pain, swelling, and joint dysfunction, seriously affecting the patient’s quality of life. While cruciate ligament rupture is less common than anterior cruciate ligament rupture, it is nevertheless a major injury that should not be taken lightly. This type of injury requires accurate clinical diagnosis and appropriate treatment. The primary emphasis of research on the posterior cruciate ligament is the investigation of the impact of surgical interventions. Historically, a significant number of clinical investigations have employed autologous hamstring tendon single-bundle restoration as a treatment for posterior cruciate ligament rupture. These studies have also confirmed its clinical effectiveness [8, 9]. Nevertheless, additional research is required to fully investigate the enduring consequences of this surgical procedure. Furthermore, there is room for improvement in various aspects, such as enhancing knee joint functionality and sustaining joint stability. Specifically, the long-term maintenance of stability requires further improvement. Simultaneously, the stability of the joint is intricately linked to the gait parameters of patients with knee cruciate ligament rupture. Consequently, there is an increased requirement for prolonged maintenance of knee joint stability in these individuals [10].

Tinga et al. demonstrated that employing high-strength braided wires in animal studies can enhance and sustain joint stability [11]. Considering the presence of these circumstances, it is possible to enhance the autologous hamstring tendon graft in patients with posterior cruciate ligament rupture. This helps to manage the reduction of its looseness and has a positive impact on maintaining long-term joint stability. However, research in this area remains inadequate. The results of this study show that the application of autologous hamstring tendon single-bundle reconstruction combined with braided thread is effective in patients with posterior cruciate ligament rupture, with a high overall rate of therapy effectiveness. Simultaneously, the joint activity indicators, gait characteristics, Rasmussen score, and KT2000 test results 1 year after treatment exhibit comparatively superior outcomes in individuals with braided threads compared to those without. This shows that the application of braided wires effectively improves the long-term treatment effect of patients with posterior cruciate ligament, and has a positive effect on improving the long-term stability and functional status of the joints. At the same time, their gait parameters are also effectively improved. According to McDonald et al., the ligament-enhanced reconstruction system can help to shorten the recovery time during the reconstruction of isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries, and has a notable effect on improving knee joint laxity [12]. In addition, Saragaglia et al. reported that the application of an artificial ligament reinforcement system based on the application of an autologous hamstring tendon graft is more helpful in improving the laxity in patients with posterior cruciate ligament, and is therefore more helpful to maintain long-term stability. All of the aforementioned factors indicate the need for further stabilization measures for patients who have had autologous hamstring tendon single-bundle repair of the posterior cruciate ligament [13]. Zhang et al. demonstrated that adding high-strength braided wires to autologous hamstring tendon grafts has a positive effect on improving joint function in patients with posterior cruciate ligament rupture [14]. Simultaneously, it also exerts a beneficial impact on enhancing the patient’s joint stability after 1 year. Hence, the application of autologous hamstring tendon single-bundle restoration in conjunction with braided thread yields superior outcomes and greater significance for individuals suffering from posterior cruciate ligament rupture.

Upon examination, it has been observed that the use of braided wires in graft applications can cause the graft to collapse and then reconstruct during its proliferation stage. These occurrences can alter the mechanics of the graft, leading to greater looseness and a reduced capacity to withstand stress. The level of joint stability is quite low, as indicated by previous research [15, 16]. The advantages of autologous ligaments are the absence of rejection reactions and reliable strength in the later stage. The early strength is insufficient and ligament laxity is prone to occur. Therefore, the main purpose of adding braided suture is to enhance the overall strength of the implant in the early stage without affecting the diameter of the ligament. The high-strength suture is re-braided to have greater strength and an elasticity of 1–2 mm at the same time, which can effectively reduce the friction between the braided suture and the tendon. Consequently, the use of braided wires on the graft significantly enhances its ability to withstand stress and strengthens its stability. This is also a crucial factor in improving joint function and gait characteristics. In addition, whether the single-bundle autologous hamstring tendon restoration is suitable for all ligament injuries remains to be verified by clinical experiments, but it is certain that the single-bundle autologous hamstring tendon restoration has a significant clinical effect on anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Xiaodong Bai’s research shows that the one-stage reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligament rupture with autologous hamstring tendon transplantation can effectively restore the stability of the knee joint, and the early postoperative knee joint function is good [17].

In conclusion, the results indicated that the application of single-bundle autologous hamstring tendon restoration in conjunction with braided threads yields superior clinical effectiveness in individuals with posterior cruciate ligament rupture, leading to a more substantial improvement in joint stability.