Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a significant medical problem worldwide. It is reported that the highest prevalence of LBP exists among women and in the population aged 40–80 years old [1]. LBP is associated with a severe economic and clinical burden in high-income countries, impacting the length of hospital stay and ambulatory visits [2].

LBP may manifest as either a dull ache or sharp discomfort and may also lead to radiating pain, particularly into the legs. It can be categorized as acute (lasting less than 4 weeks), sub-acute (4–12 weeks), or chronic (lasting over 12 weeks). While acute episodes often resolve spontaneously, with most individuals experiencing full recovery, some may progress to chronic pain despite initial improvement [3].

According to Kędra et al., spinal pain symptoms may start as soon as in children and youth in the Polish population, where over 74.4% of respondents reported back pain within the last 12 months, located mostly in the lumbar region [4]. Back pain symptoms continue further in the Polish student population [5]. According to a study conducted in 2017 on the Polish elderly population, chronic LBP was present in 42% of respondents aged 65 years or more and was associated with moderate pain [6].

Medical students often experience a higher incidence of low back pain [7–9] due to the demanding nature of their studies and clinical training. Hours spent sitting during lectures, studying, and in clinical rotations can lead to prolonged periods of sedentary behavior, which can strain the muscles and joints of the lower back and is associated with increased risk of LBP [10]. Poor posture while studying or performing clinical tasks further contribute to the risk of developing low back pain [11]. Additionally, the mental stress and pressure associated with medical school can exacerbate physical discomfort. Recent studies highlighted that depression might be a significant risk factor of LBP and resulting disability [12–14]. Moreover, depression is very common among Polish medical students [15, 16]. However, data on the prevalence of LBP among the population of Polish medical students are still lacking.

Hence, the aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of LBP among medical students at the author’s institution and estimate the resulting disability. The secondary objective was to identify subpopulations with increased LBP severity and determine possible LBP risk factors in the studied population.

Material and methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study was conducted among medical students at the Faculty of Medicine, at the author’s institution. Since the study involved an anonymous questionnaire and all invited students could decline participation, separate approval from the institutional bioethics committee was not required according to institutional regulations.

Data were collected via an anonymous online survey sent to the university mailboxes of 2614 medical students in early March 2024, with responses gathered throughout March and April 2024. The survey included questions on demographics, chronic diseases (e.g., depression, thyroid disease, migraine, atopic dermatitis, hypertension, asthma), spinal posture defects (e.g., scoliosis, pathological curvatures), spinal conditions (e.g., discopathy, intervertebral disc herniation, spinal overload pain syndrome), smoking history, physical exercise frequency and duration, maintenance of proper spine posture while sitting, approximate daily sitting duration, past and present LBP occurrence, duration, intensity (measured using a Numeric Rating Scale, NRS), and analgesic use.

The Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Index (ODI) was used to assess the disability resulting from LBP. The Polish version of this questionnaire validated on the Polish population was used [17]. The Polish version of Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) validated for the Polish adult population, which includes DSM-4 and DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing depression, was used to evaluate the prevalence of depression in the study group [18]. Point prevalence of LBP was defined as the presence of LBP during the data collection period. The duration of LBP was classified as acute, subacute, or chronic based on cut-off values of 4 and 12 weeks, respectively [3].

The study adhered to the STROBE Statement guidelines.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: active participation in university activities, good understanding of the Polish language, and consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria included a history of spinal surgery. Participants with spinal conditions and posture defects were not excluded from the study.

As the curriculum of medicine in Poland includes 6 years, with the first 3 years focusing on pre-clinical courses and the latter three including mainly classes in hospitals, participants were divided into subgroups based on their sex and participation in pre-clinical or clinical activities.

Data analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using PQStat Software (2023), PQStat v.1.8.6, Poznan, Poland. The Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that all continuous variables did not follow a normal distribution. Differences between sexes and between pre-clinical and clinical years of study were assessed using Mann-Whitney and χ2 tests. All nominal variables met Cochran’s condition after the χ2 tests and were presented as counts and percentages. Univariate logistic regression identified potential LBP risk factors, which were then included in multivariate logistic regression to determine independent risk factors. The fit of the multivariate model was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (χ2 = 6.5, p = 0.59), as well as Cox and Snell (R2 = 0.1488) and Nagelkerke (R2 = 0.21) pseudo R2 measures. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

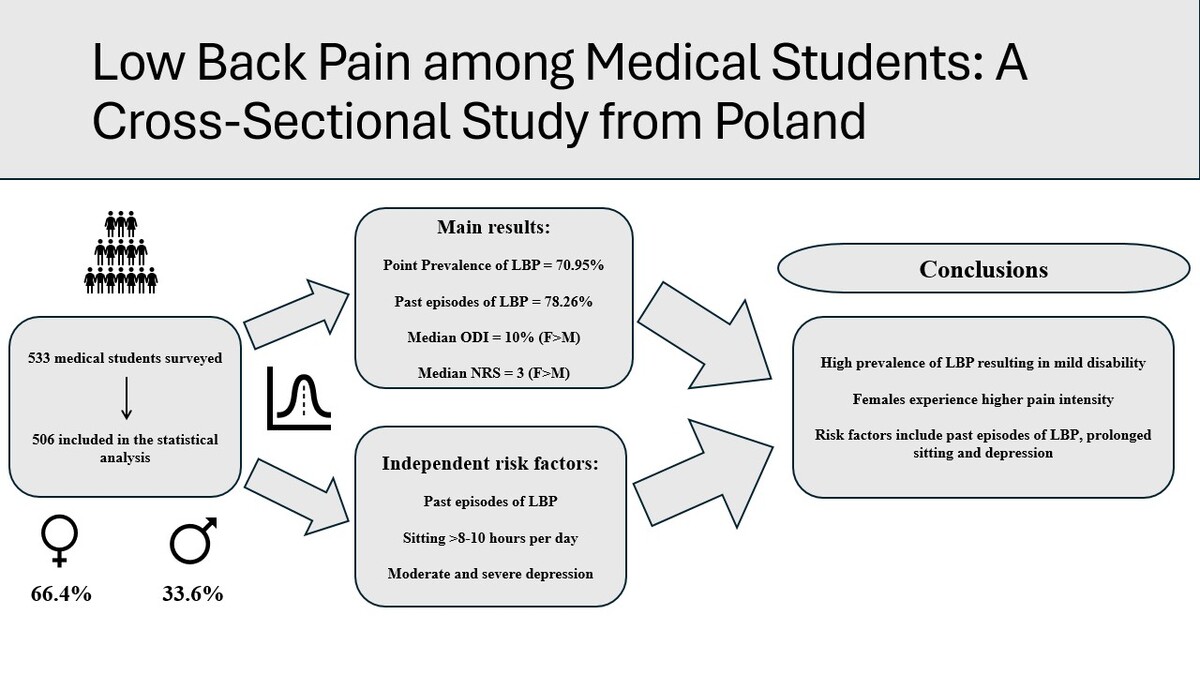

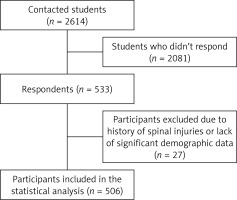

A total of 533 surveys were received, yielding a response rate of 20.39% (533/2614). Among these, 506 surveys were included in the statistical analysis (Figure 1). Twenty-seven cases were excluded because they either reported history of spine trauma (7 cases), or had missing demographic data, such as study profile, year of study, sex, age, weight, or height (20 cases).

The studied population (Table I) was predominantly female (66.4%), matching the sex distribution at the author’s institution. The median age was 22, and the median BMI was 21.56 kg/m2. About 40% reported chronic diseases, and one in four students was a smoker. Most respondents exercised weekly, usually less than three times per week. The median daily sitting duration was 8 h, with few maintaining proper spine posture.

Table I

Demographic characteristics of the studied population including comparison between individual subgroups

| Parameter | Females n = 336 (100%) | Males n = 170 (100%) | P-value | Pre-clinical n = 272 (100%) | Clinical n = 234 (100%) | P-value | Total n = 506 (100%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (Q1–Q3) | 22 (20–24) | 23 (21–24) | 0.227** | 20.5 (19–22) | 24 (23–25) | < 0.001** | 22 (20–24) |

| Median BMI (Q1–Q3) | 20.99 (19.38–22.54) | 23.03 (21.15–24.92) | < 0.001** | 21.49 (19.84–23.44) | 21.73 (19.93–23.77) | 0.545** | 21.56 (19.92–23.56) |

| Chronic disease | |||||||

| Yes | 155 (46.13%) | 51 (30%) | 0.002* | 103 (37.87%) | 103 (44.02%) | 0.105* | 206 (40.71%) |

| No | 170 (50.6%) | 111 (65.29%) | 158 (58.09%) | 123 (52.56%) | 281 (55.53%) | ||

| No data | 11 (3.27%) | 8 (4.71%) | 11 (4.04%) | 8 (3.42%) | 19 (3.76%) | ||

| Spinal-related diseases | |||||||

| Yes | 34 (10.12%) | 11 (6.47%) | 0.133* | 22 (8.09%) | 23 (9.82%) | 0.476* | 46 (9.09%) |

| No | 286 (85.12%) | 147 (86.47%) | 235 (86.40%) | 198 (84.62%) | 433 (85.57%) | ||

| No data | 16 (4.76%) | 12 (7.06%) | 15 (5.51%) | 13 (5.56%) | 27 (5.34%) | ||

| Posture defects | |||||||

| Yes | 107 (31.85%) | 32 (18.82%) | 0.005* | 76 (27.94%) | 62 (26.50%) | 0.667* | 139 (27.47%) |

| No | 213 (63.39%) | 126 (74.12%) | 182 (66.91%) | 159 (67.95%) | 339 (70.00%) | ||

| No data | 16 (4.76%) | 12 (7.06%) | 14 (5.15%) | 13 (5.55%) | 28 (5.53%) | ||

| Smoking | |||||||

| Yes | 85 (25.3%) | 41 (24.12%) | 0.758* | 75 (27.57%) | 51 (21.79%) | 0.142* | 126 (24.9%) |

| No | 250 (74.4%) | 129 (75.88%) | 197 (72.43%) | 182 (77.78%) | 379 (74.9%) | ||

| No data | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.43%) | 1 (0.2%) | ||

| Frequency of exercise | |||||||

| I don’t exercise | 45 (13.39%) | 18 (10.59%) | 0.013** | 33 (12.13%) | 30 (12.82%) | 0.93** | 65 (12.38%) |

| < 3 times per week | 199 (59.23%) | 81 (47.65%) | 161 (59.19%) | 119 (50.85%) | 278 (55.60%) | ||

| 3 times per week | 42 (12.5%) | 37 (21.76%) | 36 (13.24%) | 43 (18.38%) | 79 (15.52%) | ||

| > 3 times per week | 48 (14.29%) | 33 (19.41%) | 39 (14.34%) | 42 (17.95%) | 81 (15.91%) | ||

| No data | 2 (0.06%) | 1 (0.59%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.59%) | ||

| Maintenance of proper spine posture during sitting | |||||||

| Yes | 5 (1.49%) | 7 (4.12%) | 0.004** | 6 (2.21%) | 6 (2.56%) | 0.139** | 12 (2.37%) |

| I’m trying | 155 (46.13%) | 96 (56.47%) | 127 (46.69%) | 124 (52.99%) | 251 (49.6%) | ||

| No | 176 (52.38%) | 67 (39.41%) | 139 (51.10%) | 104 (44.44%) | 243 (48.02%) | ||

| Median duration of exercise per day [h] (Q1–Q3) | 1 (0.5–1) | 1 (0.5–2) | 0.009** | 1 (0.5–1.5) | 1 (0.5–1) | 0.308** | 1 (0.5–1.25) |

| Median duration of sitting per day [h] (Q1–Q3) | 8 (6–10) | 8 (6–8) | 0.003** | 8 (6–10) | 8 (6–8) | 0.001** | 8 (6–10) |

Females significantly more frequently reported chronic diseases than males, and posture defects were more prevalent among them. They also exercised less frequently and for shorter durations. Additionally, females sat for longer hours and maintained proper spine posture less frequently during this activity. Comparatively, pre-clinical year medical students sat for significantly longer hours than clinical year students.

In the entire cohort, the point prevalence of LBP, as well as past history of LBP were high (Table II). Over half of the participants experienced LBP symptoms for more than 12 weeks, and one in fourteen took painkillers for LBP. The median NRS indicated mild pain, while the median ODI and PHQ-9 indicated mild disability and mild depression, respectively.

Table II

Overall results including comparison between individual subgroups

| Parameter | Females n = 336 (100%) | Males n = 170 (100%) | P-value | Pre-clinical n = 272 (100%) | Clinical n = 234 (100%) | P-value | Total n = 506 (100%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point prevalence LBP | |||||||

| Yes | 246 (73.21%) | 113 (66.47%) | 0.164* | 204 (75.00%) | 155 (66.24%) | 0.039* | 359 (70.95%) |

| No | 90 (26.79%) | 57 (33.53%) | 68 (25.00%) | 79 (33.76%) | 147 (29.05%) | ||

| Past history of LBP | |||||||

| Yes | 264 (78.57%) | 132 (77.65%) | 0.914* | 209 (76.84%) | 187 (79.91%) | 0.482* | 396 (78.26%) |

| No | 72 (21.43%) | 38 (22.35%) | 63 (23.16%) | 47 (20.09%) | 110 (21.74%) | ||

| Duration of LBP | |||||||

| – | 81 (24.11%) | 56 (32.94%) | 0.136** | 66 (24.26%) | 71 (30.34%) | 0.711** | 137 (27.07%) |

| < 4 weeks | 30 (8.93%) | 12 (7.06%) | 24 (8.82%) | 18 (7.69%) | 42 (8.3%) | ||

| 4–12 weeks | 40 (11.9%) | 16 (9.41%) | 39 (14.34%) | 17 (7.26%) | 56 (11.07%) | ||

| > 12 weeks | 184 (54.76%) | 86 (50.59%) | 143 (52.57%) | 127 (54.27%) | 271 (53.56%) | ||

| Painkiller usage | |||||||

| Yes | 32 (9.52%) | 4 (2.35%) | 0.005* | 22 (8.09%) | 14 (5.98%) | 0.456* | 36 (7.11%) |

| No | 304 (90.48%) | 166 (97.65%) | 250 (91.9%) | 220 (94.02%) | 470 (92.89%) | ||

| Median NRS | 3 (2–5) | 2.5 (1–3.75) | < 0.001** | 3 (2–5) | 3 (1–4) | 0.009** | 3 (2–4) |

| Median ODI score (%) (Q1-Q3) | 12 (6–20) | 8 (2–14) | < 0.001** | 10 (6–16.5) | 10 (2.7–16) | 0.476** | 10 (4–16) |

| Median PHQ-9 score (Q1-Q3) | 7.5 (5–12) | 5 (3–9.75) | < 0.001** | 8 (5–13) | 5 (3–9) | < 0.001** | 7 (4–11) |

Female medical students reported significantly higher painkiller intake than males. Additionally, the median NRS score was statistically significantly higher in this subgroup, as were the median ODI and median PHQ-9 scores. The point prevalence of LBP among pre-clinical year students was significantly higher than among clinical year students. The former group also experienced more severe LBP intensity (NRS) and spent substantially more time in a sitting position. There were no statistically significant differences in ODI scores between the two subgroups, while pre-clinical year students exhibited more severe depression symptoms according to the PHQ-9 questionnaire.

Univariate logistic regression indicated several potential risk factors contributing to the development of LBP (Table III). These include being a pre-clinical medical student, self-reported past episodes of LBP, sitting 8 h/day, and sitting 10 h or more per day. According to the PHQ-9 questionnaire, mild depression, moderate depression, and moderate-to-severe or severe depression are also potential risk factors associated with the development of LBP.

Table III

Univariate logistic regression results

The variables that were statistically significant were included in the multivariate logistic regression model (Table IV). The results of this model indicate that past episodes of LBP, sitting 8 h and 10 h or more, as well as, according to the PHQ-9 questionnaire, mild depression, moderate depression and moderate-to-severe or severe depression are factors independently associated with the development of LBP in the studied population.

Table IV

Multivariate logistic regression results

Discussion

This cross-sectional study evaluated the prevalence of LBP among a group of medical students from Poland, and indicated that they are more common in pre-clinical students and are often associated with prolonged sitting and previous episodes of LBP and are accompanied by signs of depression.

Prevalence

LBP is one of most common medical problems; a systematic review by Hoy et al. estimated that point prevalence in the global population was 18.3 ±11.7% [1]. In this study, 70.95% of participants experienced pain at the time of survey completion (point prevalence), which is higher than in other studies on medical students, where point prevalence was lower – for example, 25.4% in a study from Austria [19], 25.6% from Bangladesh [7], 40.5% from Saudi Arabia [20], 25.4% from Malaysia [21], 17.2% from Serbia [8], and 32.5% from India [11]. There are studies from Sudan [22] and Saudi Arabia [9, 23], where prevalence of LBP was respectively 69.3%, 66.4% and 94%; however, those studies did not specify the time frame of LBP occurrence in the question.

In our research, about 53.5% of respondents had chronic LBP (pain lasting longer than 12 weeks). Again, this is considerably higher than in other studies which measured prevalence of chronic LBP in medical student populations – 19.5% in Malaysia [21], 12.4% in Serbia [8], and 15.5% in Austria [19]. The discrepancies between our findings and others may be attributed to the fact that our surveys were collected between March and April, during the exam period, when students tend to sit and study extensively. Differences in educational demands, cultural attitudes toward physical discomfort, and health behavior norms in Poland versus other regions could also influence LBP prevalence. Additionally, the other studies were conducted in the pre-COVID period, while ours was in the post-COVID era, which may also be an influencing factor, as it could be hypothesized that the pandemic period adversely affected the frequency of back pain occurrence, especially considering that the literature suggests this [24].

Depression and LBP

Evidence predominantly indicates that chronic back pain can trigger or exacerbate symptoms of depression, and vice versa [12, 25–27]. While some studies suggest that depression may not act as a direct risk factor for spinal pain [28], this view is in the minority compared to numerous studies supporting a strong link between the two. Our study demonstrated an association between LBP and depressive symptoms, aligning with other research conducted among medical students [11, 29, 30]. It can be assumed that that altered pain perception, decreased physical activity, and heightened inflammatory responses can all contribute to the prevalence and severity of LBP in those experiencing depression. Additionally, medical students experiencing mental distress may engage less in physical activity, compounding their risk of developing or worsening LBP.

Sedentary lifestyle

Sedentary behaviors during work and leisure are linked to a moderately increased risk of LBP in all age groups [10]. Unsurprisingly, in this study nearly two thirds of students were sitting for 8 h or more, and there was a strong association between prolonged sitting and LBP disability. Our data further suggest that addressing sedentary behavior in medical curricula could help mitigate LBP risks. In contrast, a Saudi Arabian study reported only 16.1% sitting over 8 h and about 30% sitting between 4 to 8 h, also linking over 8 h of sitting to increased LBP risk [9]. In Bangladesh, 31% sat for more than 6 h daily, showing a significant correlation with increased LBP [7]. A Brazilian study found a median sitting time of 8 h but no significant correlation with back pain [30]. Similarly, an Austrian study with a median sitting time of 12 h found no correlation with LBP [19]. These differences may stem from varying lifestyles, posture habits, and approaches to physical activity among medical students in different countries.

Posture

In our study, only 2.2% maintained the correct posture, and about half of the respondents said that they tried to maintain it most of the time. Many studies focusing on medical students have found a significant correlation between maintaining good posture and reducing back pain [8, 11, 30]. In a study from Saudi Arabia [9], 44.3% of respondents indicated that one of their methods for reducing back pain is maintaining correct posture and in a study from Belgrade it was around 54% [8]. In our study we identified that not maintaining proper spine posture during sitting may potentially contribute to the development of LBP; however, it is not an independent risk factor.

Sex

In nearly every study conducted on medical students, females were more predisposed to experience spinal pain [7, 8, 11, 30, 31]. An exception was noted in a study from Saudi Arabia, where no correlation between sex and spinal pain was demonstrated [9]. In this series, females had a higher risk of LBP and higher degrees of disability. This could be related to the fact that women in our survey were less likely to engage in physical exercise and maintain proper spine position during sitting; however, there is not sufficient evidence to support this hypothesis, and logistic regression models were unable to demonstrate female sex as a risk factor contributing to the development of LBP.

BMI and exercise

In the general population, body mass index (BMI) appears to play an important role, as overweight and obesity are strongly associated with seeking medical care for low back pain and chronic low back pain according to literature [32]. However, in our study, BMI was not associated with LBP, although it is worth mentioning that the majority of respondents had BMI within the normal range. Most authors demonstrated increased risk of LBP in students with higher BMI [7, 9, 20]; however, this was not confirmed in all studies [11].

A meta-analysis of 61 randomized controlled trials on LBP and exercising found that exercise therapy seems to be slightly effective at decreasing pain and improving function in adults with chronic LBP, however, it does not have a significant effect on acute LBP [33]. Most of the studies on medical students support the thesis that the prevalence of LBP is lower in those who exercise more frequently [7–9, 19, 21, 23]. Studies from Brazil [30] and India [11] did not find a correlation between exercising and LBP; similarly, this study did not identify lack of physical exercises as a risk factor contributing to the development of LBP. The inconsistency in findings may be due to differences in exercise types, intensity, and frequency, as well as individual variability in physical fitness levels and lifestyle habits among study populations.

Pain intensity and painkillers

In our study, the median pain intensity was rated as 3 on the Numeric Rating Scale, which aligns with findings from other studies. Specifically, the median NRS score was 3 in a study from China [31], 4 in a study from Brazil [30], and 3.91 in a study from Saudi Arabia [9].

Regarding the use of painkillers for managing LBP, 7.5% of respondents in our study reported taking painkillers due to the occurrence of LBP. This rate is identical to that found in a study from Saudi Arabia [9]. In contrast, a study from Brazil reported that 56.1% of those with LBP would take painkillers occasionally, and 43.9% would take them from once a week to daily [30]. Meanwhile, a study from Bangladesh found that 22.1% of respondents admitted to taking opioid medications for LBP [7]. Differences in the frequency of taking painkillers might stem from cultural differences or awareness and education about potential harms of using those medications.

Clinical years and pain

Our research indicates that students in the pre-clinical stages of their education suffer from more intense back pain and spend more time sitting compared to students in clinical stages. This increased severity of LBP in pre-clinical students could be attributed to extended periods of sitting during study sessions and lectures, which are less frequent in the more physically active clinical years. Furthermore, multiple studies have shown a notable correlation between the year of study and the occurrence of musculoskeletal pain in medical students [20, 21, 34, 35]. This was however challenged by other authors [7, 30, 36].

Limitations

First, the use of a self-reported online questionnaire introduces the risk of bias, as responses may be influenced by participants’ perceptions or willingness to disclose information. Second, the study has a relatively low response rate due to the inclusion procedure, although it is comparable to other cross-sectional studies. Individuals with LBP might have been more inclined to participate, potentially overestimating LBP prevalence. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between identified risk factors and LBP, capturing only a short-term snapshot of the studied population. Although the power was high and the effect size moderate when analyzing the main variables with the Mann-Whitney test, both power and effect size were lower for variables tested with the less robust χ2 test, reducing the practical significance of these variables’ results. Finally, due to the specific organization of medical studies, the results cannot be generalized to other groups of students or young adults.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated a high prevalence of LBP among medical students, associated with mild depression and disability. These findings underscore the urgent need for early prevention and effective management strategies to address LBP in this population. Without intervention, acute LBP may progress to chronic pain, significantly reducing quality of life, shortening career longevity, and limiting the professional activity of future healthcare professionals. This concern is particularly relevant, as previous research has consistently shown that LBP represents a major challenge among medical personnel [37].

Factors associated with LBP included past episodes, prolonged sitting, and depression symptoms. To address these issues, medical universities, in collaboration with clinical hospitals, should focus on implementing preventive programs tailored to the needs of medical students. These measures could include early education on LBP prevention, emphasizing proper sitting posture, regular spinal health exercises, and ergonomic solutions to reduce physical strain during study sessions. Given that clinical training often takes place in hospital settings, medical institutions should also promote awareness of LBP risks and provide ergonomic assessments within clinical environments. Expanding access to psychological support services is essential, given the strong association between depressive symptoms and LBP. Furthermore, integrating these preventive and supportive measures into the existing healthcare framework within medical institutions could provide a more coordinated approach to managing LBP risks among medical students.