Introduction

Hysteroscopy is a common endoscopic procedure performed under general and local anesthesia. It is currently considered the gold standard for the diagnosis and treatment of various conditions including abnormal uterine bleeding, endometrial polyps, and submucous myomas [1–6]. As hysteroscopy allows direct visualization as well as treatment of lesions, it is an ideal alternative to the procedures of uterine cavity curettage performed under general anesthesia [7]. Initially, hysteroscopy was carried out using an endoscope with a diameter of 10 mm or more, a speculum, tenaculum forceps, and dilators, which enabled the dilation of the cervical canal [8]. However, due to accompanying pain, this procedure required general anesthesia [8, 9]. Nowadays, resectoscopes with a reduced diameter are widely used for hysteroscopy. The advent of modern minihysteroscopes, which do not necessitate the dilatation of the cervical canal, has made it possible to perform hysteroscopy with only local anesthesia rather than short-term general anesthesia [10, 11]. Hysteroscopy under local anesthesia offers significant advantages over the procedure performed under general anesthesia, e.g. a reduction in the risk associated with general anesthesia, decreased costs, and shorter hospital stay [12, 13]. The use of hysteroscopes with smaller diameters does not guarantee a painless procedure [14]. Also surgery under local anesthesia is not always successful due to increased pain and risk of vasovagal reaction [8, 15]. Data from the literature indicate that 1.3–5.2% of procedures cannot be performed due to pain intolerance [16]. The severity of pain may be determined not only by technical aspects but also by the experience of the surgeon, duration of the procedure, abnormalities of the genital tract, and psychological profile of the patient [1].

Studies on major gynecological procedures often use the visual analog scale (VAS) [17]. VAS is a proven and sensitive tool for the assessment of pain. It avoids vague descriptions of pain that can be difficult for a patient to understand and also allows a comparison of measurements over time [18]. However, only a few studies have examined the level of pain experienced during hysteroscopy under local anesthesia, and thus, it is important to investigate this aspect. With increasing availability of ultrasound examination, uterine cavity abnormalities are being increasingly diagnosed, and hence there is a need to determine the best treatment option for patients [19].

The aim of this study was to assess the level of pain experienced by patients during minihysteroscopy under local anesthesia, with the use of VAS.

Material and methods

The study included patients who were undergoing diagnostic and surgical minihysteroscopy in the Gynecological-Obstetrical Clinical Hospital of Poznan University of Medical Sciences, during 2020–2021.

Patient selection for surgery

The eligibility criteria for minihysteroscopy procedures under local anesthesia (with lignocaine) included abnormal uterine bleeding, endometrial polyps or submucous myomas, and endometrial hyperplasia. Furthermore, the patients included in the study were in the first phase of the menstrual cycle or in the postmenopausal period and were scheduled for surgery after gynecological and ultrasound examination. All women reported good health without cardiovascular diseases and negative history of lignocaine and ketoprofen allergy. Those diagnosed with heavy genital bleeding, vaginal and/or cervical inflammation, and inability to exclude pregnancy during presurgical evaluation were excluded.

Data collection

A medical history was collected during presurgical evaluation, and the patients were asked about their age, body weight and height, history of operations, allergies, number and type of deliveries, number of miscarriages, previous cervical and endometrial procedures, and general health status.

Pain was assessed using the VAS. During presurgical evaluation, the principles of VAS pain assessment were explained to each examined woman. After the procedure, the patients were asked to indicate their pain severity based on the VAS. The VAS was used to assess the pain experienced during the procedure on a scale of 0–10. The pain level was classified as follows: 0 points – no pain, 1–3 points – mild pain, 4–7 points – moderate pain, and 8–10 points – severe pain [18].

Surgery procedures

After gynecological examination and transvaginal ultrasound, signed consent for the hysteroscopic procedure was obtained from each patient. Thirty minutes before the start of the procedure, 100 mg of ketoprofen was intravenously administered to the patient. During the procedure, vital functions, such as heart rate, blood pressure, O2 saturation, and respiratory rate, were monitored. Ten minutes before the minihysteroscope was inserted into the cervical canal, 10 ml of 0.1% lignocaine solution was paracervically administered in two injections (the first 10 ml at 4 o’clock and the second 10 ml at 8 o’clock) at a needle insertion depth of about 2 mm. Hysteroscopy was performed without inserting tenaculum forceps and a speculum in the vagina.

Operators who had experience in hysteroscopy performed the procedure. The patients were first placed on a “treatment table” in a position used for gynecological examination. The uterine cavity was dilated with 0.9% NaCl solution administered with continuous flow at a pressure of 110 mm Hg. Hysteroscopy was performed using the GUBBINI Mini Hystero-Resectoscope system with a working diameter of 16 Fr. Being a certified center and working on the GUBBINI system, we adapted the procedure of pericervical anesthesia to Polish conditions, using lignocaine (a preparation with a smaller cardiotoxic effect than bupivacaine) and ketoprofen.

Based on the reported symptoms and abnormalities found on ultrasound examination and the type of procedure performed, the patients were divided into two groups: diagnostic hysteroscopy (HD) and surgical hysteroscopy (HO). The HD group consisted of women (n = 86) aged 46.29 ±9.55 years (median (Me): 45 years), who reported abnormally heavy uterine bleeding. These patients had an endometrial biopsy before the planned laparoscopic supracervical uterine removal surgery. During the procedure, 3 pieces of endometrium with a volume up to 0.5 ml were collected. The HO group consisted of women (n = 56) aged 45.38 ±13.04 years (Me: 43 years), with ultrasound-confirmed diagnosis of endometrial polyps or submucous myomas. The diameter of the lesions within the uterine cavity ranged from 0.5 cm to 1.5 cm. During the procedure, the patients were conscious and could observe the procedure in real time on a monitor.

Ethics statement

The methods used for patient enrollment and collection and storage of research material were approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Poznan University of Medical Sciences (Resolution No. 828/20 of 14.01.2021).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out using Statistica (TIBCO Software Inc. 2017, data analysis software system, version 13) and Microsoft Excel (version 2019, Microsoft Office). The distribution of variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Homogeneity of variance was assessed using Levene’s and Brown-Forsythe tests. Student’s t-test, the Mann-Whitney U test, and Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance were used for comparisons between groups. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05 for all calculations.

Results

Characteristics of the study group

A total of 142 women were included in the study. The age of the subjects ranged from 22 to 80 years, and their average age was 44 years (45.93 ±11.02). The body mass index (BMI) values of the subjects ranged from 17.72 to 41.98 kg/m², and their mean BMI was 24.97 kg/m² (26.14 ±5.28). No statistically significant differences were noted between the type of hysteroscopic procedure performed and the patient age, BMI, body mass score, or presence of comorbidities (Table I).

Table I

Clinical characteristics

Among the studied patients, 90.7% in the HD group and 67.86% in the HO group reported obstetric history of pregnancy. Women in the HD group were characterized by a higher number of past pregnancies (p < 0.001). A total of 25 (17.61%) subjects reported a history of miscarriage, including 17 (19.77%) in the HD group and 8 (14.29%) in the HO group. Sixty-one (70.93%) patients in the HD group and 32 (57.14%) in the HO group reported natural childbirth. No correlation was observed between the type of minihysteroscopy procedure performed and the number of natural deliveries. Among the studied subjects, 29 (20.42%) reported delivery by cesarean section. The patients in the HD group reported a significantly higher number of deliveries by cesarean section (24 vs. 5; p = 0.006). The obstetric history indicated that women in the HO group had significantly fewer offspring (p = 0.001) than those in the HD group (Table II).

Table II

Obstetric history vs. type of hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy

The procedures lasted from 13 to 37 min. The mean duration of hysteroscopy was 25 min (23.54 ±5.38). There were no significant differences in the procedure time based on the type of hysteroscopy. No association was found between the procedure time and patient BMI or age. However, it was noted that in the HD group, a shorter procedure time was associated with a higher number of natural deliveries (τ = –0.15; p = 0.035). In contrast, in the HO group, a higher number of miscarriages was associated with a shorter procedure time (τ = –0.27; p = 0.003). Among the studied women, 26 (18.31%) had previously undergone minor gynecological procedures (uterine cavity curettage), including 15 (17.44%) in the HD group and 11 (19.64%) in the HO group. No significant relationship was observed between the type of minihysteroscopy and the history and/or number of minor gynecological procedures (Table III).

Table III

Previous procedures, time and VAS vs. type of hysteroscopy

VAS

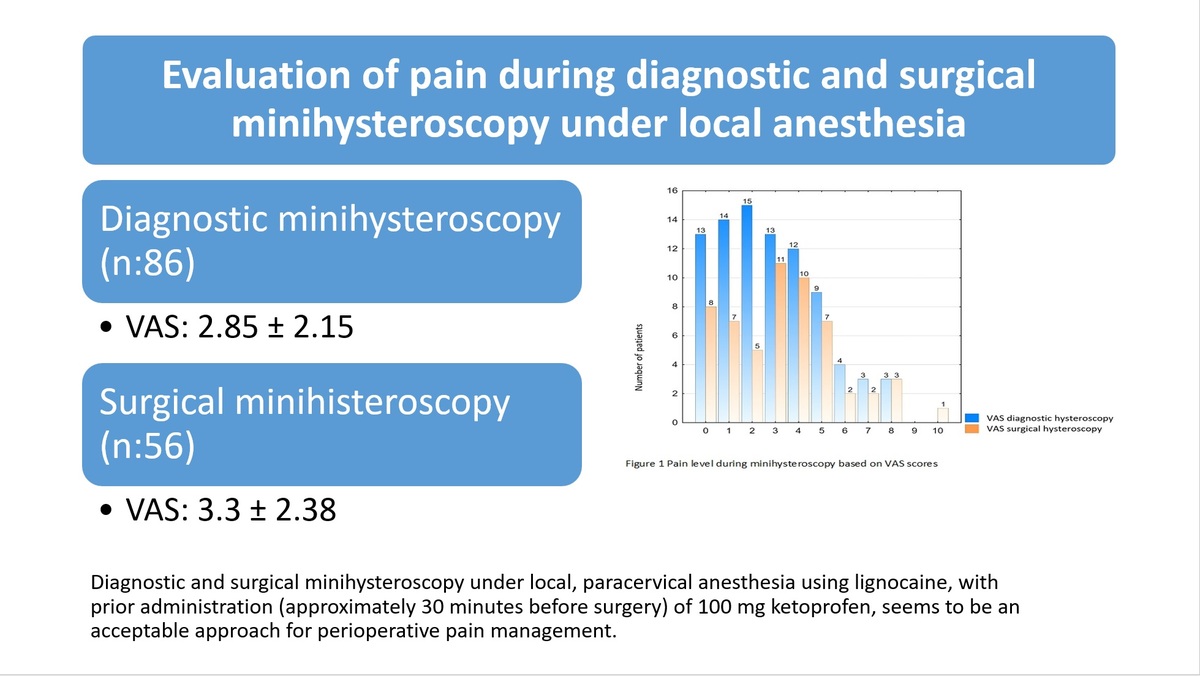

The average intensity of pain during the procedure was rated at 3 points (3.03 ±2.25 points) (Figure 1). No differences in pain scores were found with respect to the type of minihysteroscopy procedure performed (Table III). During the assessment of pain after surgery, 21 (14.8%) patients reported no pain, while mild pain (1–3 points) was reported by 65 (45.8%), moderate pain (4–7 points) by 49 (34.5%), and severe pain (8–10 points) by 7 (4.9%). No statistically significant relationship between the VAS score and BMI or age of the subjects was noted. In the HO group, a higher number of deliveries by cesarean section was associated with a lower pain score (τ = –0.2; p = 0.03). It was also noted that as the duration of the procedure increased (regardless of the type), the level of pain experienced increased (r = 0.17; p = 0.0495).

Discussion

Hysteroscopy has been the gold standard for evaluating the pathology of the cervical canal and uterine cavity in both premenopausal and postmenopausal patients. Minihysteroscopy, performed using miniature hysteroscopic equipment, shortens the recovery time and effectively integrates clinical practice with a “see-and-treat” mode, while avoiding the risk of anesthesia and inconvenience of the operating room [20]. Many efforts have been made in the past 20 years to promote the wide use of the minihysteroscopy procedure. However, minihysteroscopy is still considered painful, with some women reporting discomfort at various stages of the procedure [21]. In addition, unpleasant sensations may be compounded by high levels of anxiety about the procedure [21]. It has been reported that pain is the most common reason for discontinuation of the surgical procedure [22]. For this reason, pharmacological (administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, antispasmodics, local anesthetics, prostaglandins, and opioids) and nonpharmacological (percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, uterine relaxation, adequate fluid pressure during uterine entry, heating and type of medium used for the procedure, hypnosis, music, talking to the patient) approaches for intraoperative and postoperative pain relief have been used in women undergoing minihysteroscopy, with results varying in different groups [22]. Abis et al. [23] reviewed the different types of pain relief methods available. Their study indicated that routine pre- or intraoperative analgesia was used by 34% of surgeons (67% of them used NSAIDs, 12% paracetamol, 7% opioids, 13.5% other). Among the operators who routinely used intraoperative analgesia, 46.1% used paracervical block and 15.4% used intracervical block, 3.8% used local anesthesia (spray or gel on the cervical surface), and 19.2% used another method, while 15.4% encouraged patients to listen to music during the surgery. Regarding misoprostol, 75% of hysteroscopists reported that they do not use it routinely [23]. In our study, we compared the level of pain reported by patients undergoing diagnostic and surgical minihysteroscopy procedures under local, paracervical anesthesia using lignocaine with prior administration (approximately 30 min before surgery) of 100 mg of ketoprofen. The mean pain reported by female patients in this study based on the VAS was 3, which implies that the pain perceived was mild or moderate pain. The rest of the patients in the study reported 4 or more points on the scale, which may support the hypothesis that hysteroscopy may be moderately painful in some patients. Similar results were obtained in the study by Pegoraro et al. [24], in which 41.7% of patients who underwent hysteroscopy for infertility diagnosis rated pain at 4 or more points [24] (Table IV). Other studies of mixed populations (with different indications for hysteroscopy) found that the percentage of women who reported pain at 4 points on the VAS varied over a wide range (21–88%), with a mean pain score of 1.8–6.2 points. The pain values may depend, among other factors, on reproductive status, operator experience, dilating medium, ethnicity, patient stress, and diameter of surgical instruments [14, 18, 25–27] (Table IV). According to De Silva et al. [28], saline should be administered at the lowest pressure during minihysteroscopy to dilate the uterus for a satisfactory view and pain reduction [28]. Pain induced by the passage of the minihysteroscope through the cervical canal is also associated with cervical dilation. Women who had natural deliveries have a more dilated cervix, and thus experience less pain during the procedure, and the procedure time is also shorter [27–29]. In our study, we observed that in the HD group, a shorter procedure time was associated with a higher number of natural deliveries in the history, whereas in the HO group, a higher number of miscarriages was associated with a shorter procedure time. In turn, a shorter procedure time was associated with a lower VAS score. Samy et al. [30] found that the use of lidocaine and tramadol resulted in effective pain reduction in postmenopausal patients during and after diagnostic minihysteroscopy. However, after lidocaine infusion into the uterine cavity, the timing of the minihysteroscope passage through the cervical canal was associated with less pain as assessed by the VAS [30] (Table IV). In a similar study, Hassan obtained similar VAS results in the groups of patients in which tramadol and placebo were used [31]. In the study of Al-Sunaidi, the VAS values were found at the level of 2.1 and 3.2 with the use of lorazepam p.o., intra- and paracervical anesthesia with bupivacaine [32] (Table IV). According to Ying Law, listening to music may influence pain assessment by the VAS [33]. In a study on the Chinese population, the author examined whether listening to music during hysteroscopy reduced pain. The results indicated that music reduced pain by 1.3 points, and therefore routine use of music during hysteroscopy can improve patient care [33]. These results are not confirmed by the earlier work of Mak et al., who found that listening to music may be a factor distracting the operator [34] (Table IV).

Table IV

VAS results in other studies

Other studies have revealed that vasovagal reactions occur during hysteroscopy. Coimbra [35] observed vasovagal reactions such as bradycardia, hypotension, syncope, sweating, nausea, or vomiting during or after the procedure [35]. In our study, we did not record such a reaction during the procedure. The occurrence of vasovagal reaction may be associated with the use of perioperative anesthesia with lidocaine, which has been confirmed by Zupi [36] and Elasy et al. [37].

Besides pain, another frequently studied factor is the anxiety level of patients, which was not assessed in this study. Anxiety before surgery is assessed using the Illness Perception Questionnaire [29, 38, 39]. Anxiety, in addition to pain, may hinder the procedure and thus translate into a negative patient experience [29]. The factors associated with pain during hysteroscopy have not been studied in detail so far [40]. There is also consistent evidence clearly indicating the safest and most effective pain relief option for women undergoing hysteroscopy [41]. Therefore, efforts should be made to help identify those who are at a higher risk of experiencing pain. The overarching goal is to provide adequate pain management during minihysteroscopy procedures, in order to reduce discomfort and satisfy both the patient and the operator.

The main advantages of this study at the Hysteroscopy Center under Local Anesthesia are: conducting the study on a large number of patients, repeatability of treatment conditions, treatments being performed by a small group of qualified operators based on the same technique and equipment, using the same anesthesia for each patient.

As a team, we are convinced that further research will lead to the popularization of this method and the introduction of standards in hysteroscopic procedures.

In conclusion, diagnostic and surgical minihysteroscopy under local, paracervical anesthesia using lignocaine, with prior administration (approximately 30 min before surgery) of 100 mg of ketoprofen, seems to be an acceptable approach for perioperative pain management. The results of the study suggest that hysteroscopes with a smaller diameter and paracervical block can be successfully used in outpatient medical practice.