Introduction

Owing to significant improvements in healthcare allowing a longer life expectancy, the number of very elderly persons (≥ 80 years old) is rising worldwide, with an estimated three-fold increase from 2015 (126.5 million) to 2050 (446.6 million) [1–3].

Alongside a vulnerability to disability and illness, the very elderly population is known to have a high prevalence of chronic diseases, multi-morbidity, frequent hospital admissions and high in-hospital mortality rates [4–6]. This emphasizes the critical importance of estimating the risk of in-hospital mortality in managing very elderly hospitalized patients in terms of clinical decision-making in identifying individuals appropriate for palliative care or targeted interventions or treatments along with the risks and benefits of potential treatments [4, 5, 7, 8].

Alongside C-reactive protein (CRP) level, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and platelet (PLT) indices (i.e. mean platelet volume (MPV) and PLT/MPV ratio) have recently emerged as inexpensive and readily available new potential thrombo-inflammatory markers and predictors of major adverse outcomes and mortality in various cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases [9–11]. However, limited data are available on the potential utility of these inflammatory indices as markers for adverse clinical outcomes, particularly in terms of in-hospital mortality risk, in the very elderly population [3, 5, 8, 12].

This study was therefore designed to evaluate the potential role of inflammatory markers (NLR, PLR, PLT/MPV, CRP and CRP/albumin) as well as demographic, clinical and laboratory parameters in predicting mortality risk among very elderly hospitalized patients.

Material and methods

Study population

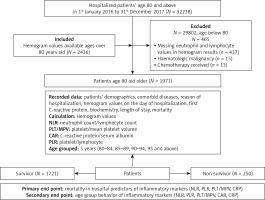

Of the total of 32,238 patients hospitalized between January 2016 and October 2017 at our hospital, 2433 very elderly (aged ≥ 80 years) patients hospitalized due to acute respiratory conditions were included in this retrospective cross sectional study. Patients hospitalized between 2016 and 2017 who were over 80 years of age at the time of hospital admission and who had complete blood count (CBC) records at the time of hospital admission were included in the study. Patients aged < 80 years and those without available CBC records were excluded from the study. Accordingly, 2436 out of 1971 enrolled patients were subjected to the final analysis with exclusion of 3 patients who died within the first couple of hours of emergency admission and thus had no available CBC records on the day of admission (n = 437), hematologic malignancy (n = 15), under chemotherapy (n = 13) (Figure 1).

The study was approved by University of Health Sciences Sureyyapasa Chest Diseases and Thoracic Surgery Training and Research Hospital Scientific Research Committee on the date 12.07.2018, number 044, and it was conducted in full accordance with local Good Clinical Practice guidelines and current legislations, in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, patient’s signed informed consent was not required by the Scientific Research Committee.

Study parameters

Data on patient demographics, co-morbid diseases (diabetes, hypertension, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD), atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, Alzheimer, cerebrovascular sequela, gastrostomy feeding, having tracheostomy, interstitial lung disease, lung cancer, bronchiectasis, chronic renal failure) and hospitalization unit (ward, intensive care unit (ICU), palliative care unit (PCU)), pulmonary disease related reasons for hospitalization (pneumonia, sepsis, pulmonary emboli, pleurisy, tuberculosis, malnourishment, renal failure), length of hospital stay (LOS, day), ICU severity score as Acute Physiologic And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores, mortality, and laboratory findings including complete blood count, inflammatory markers (NLR, PLR, PLT/MPV ratio, CRP and CRP/albumin ratio) and blood biochemistry findings were obtained from the hospital electronic medical record system. Study variables were evaluated with respect to hospitalization unit and survivorship status.

Inflammatory markers

CBC counts including total leukocyte, neutrophil, eosinophil, lymphocyte, platelet counts, and MPV were determined using a Coulter LH 780 Hematology Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Atlanta, GA, USA). CRP was determined using the nephelometry method BN II System (Siemens, Munich, Germany). NLR was calculated as total neutrophil count divided by total lymphocyte count. PLR was calculated as PLT count divided by total lymphocyte count. CRP to albumin ratio was calculated as serum CRP level (mg/l) divided by serum albumin level (g/dl).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Data were expressed as “mean (standard deviation; SD)”, percent (%) and median (25-75%) where appropriate. The χ2 test was used to analyze categorical data, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used for analysis of numerical data. Three groups comparisons were done by ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test according to dispersion. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve was plotted to determine performance (sensitivity, specificity) of inflammatory marker levels in identification of in-hospital mortality risk with calculation of AUC values and ideal cut-off value. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine factors predicting in-hospital mortality risk. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Overall, mean ± SD age was 84 ± 4 years and males composed 51.8.0% of the study population. Age was stratified according to 5-year intervals and age of half of patients was above 85. The major first three reasons of hospitalization were acute on chronic respiratory failure, pneumonia and pleurisy. Median LOS was 6.0 days and in-hospital mortality rate was 12.7% (n = 250) (Table I).

Table I

Age 80 and above patients’ characteristics and reason for hospitalization and hospital outcome

All studied inflammatory markers showed significant difference between hospitalization units (Table II).

Table II

Inflammatory markers according to hospitalization place

| Parameter | Location | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ward (a) (N = 1470) | ICU (b) (N =352) | Palliative care (c) (N = 149) | |||||

| N | Median | N | Median | N | Median | ||

| NLR | 1470 | 5.96 (3.53–11.0) | 352 | 7.81 (4.35–16.86) | 149 | 8.33 (3.91–22.00) | < 0.001 |

| CRP* | 1342 | 20.1 (7.7–52.1) | 313 | 60.7 (24.2–133.0) | 91 | 67.1 (26.0–125.0) | < 0.001 |

| CAR# | 558 | 6.71 (2.20–17.24) | 126 | 26.61 (8.06–61.57) | 36 | 25.28 (9.55–47.07) | < 0.001 |

| PLR | 1469 | 216.67 (147.50–325.0) | 351 | 190.00 (121.25–324.00) | 149 | 258.75 (144.09–420.00) | < 0.001 |

| PLTMPV | 1469 | 28.76 (20.99–38.99) | 352 | 23.79 (14.48–32.69) | 149 | 26.13 (17.82–35.12) | < 0.001 |

Gender, hospitalization unit, reasons for admission and comorbidities according to survivorship status

No significant gender influence was noted on survivorship status, while survivorship status differed significantly with respect to hospital unit with higher likelihood of in-hospital mortality in elderly patients hospitalized in palliative care (40.9%) (Table III).

Table III

Gender, hospitalization unit and diagnosis according to survivor status

| Parameter | Survivor (N = 1721) | Non-survivor (N = 250) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender male, n (column %) | 885 (51.4) | 136 (54.4) | 0.38 |

| Age group, n (row %): | |||

| 80–84 | 872 (89.2) | 106 (10.8) | 0.001 |

| 85–89 | 626 (87.4) | 90 (12.6) | |

| 90–94 | 184 (81.4) | 42 (18.6) | |

| 95 and above | 39 (76.5) | 12(23.5) | |

| Hospitalization unit, n (row %): | |||

| Ward | 1404 (95.5) | 66 (4.5) | < 0.001 |

| Intensive care unit | 229 (65.1) | 123(34.9) | |

| Palliative care unit | 88 (59.1) | 61(40.9) | |

| Comorbid diagnoses*, n (%): | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases | 1232 (71.6) | 138 (55.2) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 778 (45.2) | 106 (42.4) | 0.40 |

| Alzheimer | 196 (11.4) | 64 (25.6) | < 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 256 (14.9) | 23 (9.2) | 0.016 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 332 (19.3) | 41 (16.4) | 0.28 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 86 (5.0) | 30 (12.0) | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 90 (5.2) | 25 (10.0) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes | 326 (18.9) | 44 (17.6) | 0.61 |

| Tracheostomy | 27 (1.6) | 3 (1.2) | 0.66 |

| Gastrostomy tube feeding | 31 (1.8) | 6 (2.4) | 0.52 |

| Congestive heart failure | 303 (17.6) | 43 (17.2) | 0.88 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 622 (16.6) | 141 (14.0) | 0.30 |

| Acute conditions, n (%): | |||

| Exacerbation of chronic obstructive diseases | 525 (30.5) | 76(30.4) | 0.97 |

| Nutritional disorder | 89 (5.2) | 53 (21.2) | < 0.001 |

| Pleural effusion | 207 (12.0) | 28 (11.2) | 0.71 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 622 (36.1) | 141 (56.4) | < 0.001 |

| Lung malignancy | 206 (12.0) | 42 (16.8) | 0.031 |

| Other malignancies | 87 (5.1) | 19 (7.6) | 0.10 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 99 (5.8) | 11 (4.4) | 0.38 |

| Bronchiectasis | 177 (10.3) | 50 (20.0) | < 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 493 (28.6) | 135 (54.0) | < 0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 321 (18.7) | 43 (17.2) | 0.58 |

| Pneumothorax# | 20 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) | > 0.99 |

| Tuberculosis | 31 (1.8) | 5 (2.0) | 0.83 |

| Acute kidney failure | 41 (2.4) | 32 (12.8) | < 0.001 |

| Sepsis | 58 (3.4) | 67 (26.8) | < 0.001 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 90 (5.2) | 24 (9.6) | 0.006 |

| Asthma attack# | 46 (2.7) | 4 (1.6) | 0.39 |

Inflammatory markers and blood biochemistry findings according to survivorship status

Mean patient age and median values for CRP, NLR and CRP/albumin ratio and PLR were significantly higher, whereas PLT/MPV was significantly lower in non-survivors than in survivors (p < 0.001 for each) (Table IV). Blood biochemistry findings revealed significantly higher serum values for glucose, urea, creatinine, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) along with significantly lower values for protein and albumin among non-survivors compared to survivors (p < 0.001 for each) (Table IV).

Table IV

Patient age and inflammatory markers and blood biochemistry findings according to survivorship status

[i] Values median (25–75%) if not mentioned, Mann-Whitney U test. Mean (SD) analyzed by Student’s t test. WBC – white blood cells, CRP – C-reactive protein, NLR – neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR – platelet to lymphocyte ratio, PLT/MPV – platelet to mean platelet volume, AST – aspartate transaminase, ALT – alanine transaminase.

The inflammatory markers are compared according to mortality in the place of admittance to hospital in Table V. The median CRP values were significantly higher in the ward than the PCU and the median NLR values were also significantly higher in the ward than the ICU and PCU in non-survivors than survivors. In the ICU, APACHE II score and CRP/albumin were significantly higher and PLT/MPV, platelet and albumin were lower in non-survivors (Table V).

Table V

Comparison of patients’ mortality groups with inflammatory markers according to hospitalization place

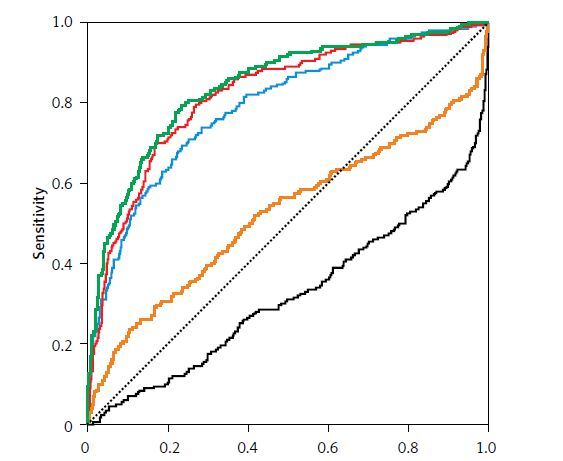

ROC analysis for performance of inflammatory markers in identification of mortality risk in hospital revealed that NLR, PLT/MPV, CRP/albumin ratio, and CRP levels with cut-off values were potential markers of in-hospital mortality risk in very elderly hospitalized patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2

ROC curve analysis for the role of inflammatory markers in discriminating non-survivors among very elderly hospitalized patients. Area under the curve for mortality in hospital for elderly patients are shown in the table

ROC analysis for performance of inflammatory markers in identification of mortality risk in the ICU revealed that APACHE II score, NLR, PLT/MPV, CRP/albumin ratio, and CRP levels with cut-off values were potential markers of in-hospital mortality risk in very elderly patients in the ICU (Figure 3).

Figure 3

ROC curve analysis for the role of inflammatory markers, APACHE II in discriminating non-survivors among very elderly ICU patients. Area under the curve for mortality in Intensive Care Unit for elderly patients are shown in the table

Binary logistic regression analysis was done and age above 90, CRP = 44 and above, CRP/albumin = 13.5 and above, PLT/MPV = 26.2 × 103, NLR = 7.75 and above patients, hospitalization place, comorbid diseases (chronic renal failure, Alzheimer, interstitial lung diseases) reasons for hospitalization (acute respiratory failure, pneumonia, acute renal failure, malnourishment, sepsis, exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases) were included in the model for determining the risk of hospital mortality. Considering laboratory parameters, NLR over 7.75 (OR = 7.83, p < 0.001) was only determined to significantly predict an increased in-hospital mortality risk among very elderly patients (Table VI).

Table VI

Binary logistic regression analysis predictors for mortality in hospitalized elderly patients

Discussion

This study findings in a retrospective cohort of very elderly (age 80 and above) patients hospitalized due to respiratory diseases revealed that the in-hospital mortality rate was 12.7% and among inflammatory markers, ROC analysis of AUC showed the cut-off values of mortality in hospital for CRP above 44 mg/dl, CRP/albumin values above 13.5; NLR values above 7.75 and PLT/MPV values below 26.2. ROC analysis of AUC showed the cut-off values of mortality in elderly patients who require ICU, APACHE II values above 24, CRP values above 60 mg/dl, CRP/albumin above 26, NLR and PLT/MPV values the same as hospital mortality cut-off values. The study found that increased risk of in-hospital mortality in cases of acute and chronic renal failure, requiring ICU and palliative care unit admission, and NLR equal to 7.75 and above were significant predictors of increased risk of mortality in very elderly hospitalized patients.

Pneumonia, sepsis, bronchiectasis, acute renal failure and lung cancer at admission or co-morbid chronic renal diseases and nutritional problems, Alzheimer’s disease and stroke were also noted among non-survivors in the univariate analysis in our cohort of elderly patients. This supports the suggestion that alongside the reason for admission [5, 8], the prevalence, number and type of co-morbidities are also associated with increased mortality risk among very elderly patients, particularly for co-morbid hypertension, dementia and pneumonia [3, 13–17]. In the present study hypertension was the second most prevalent co-morbid disease after COPD; it was found at nearly the same rate among survivors and non-survivors.

Reasons for admission in our cohort also show that the elderly comprise a highly heterogeneous population with multi-comorbidities alongside a high risk of frailty and vulnerability to inability to cope with stressors, such as hospitalization or acute illness [18]. In the present study, the mortality rate according to admitted place of hospital revealed that palliative care admitted patients had a higher mortality rate because of various underlying terminal state diseases.

Notably, hospitalization in respiratory diseases with the diagnosis of COPD was more prevalent in survivors than in non-survivors in our cohort. This seems consistent with data from a past study from Turkey, which indicated an increase in prevalence and similarly good outcome of COPD-related hospitalizations in very elderly patients from 2008 to 2014 [12]. In addition, statistically significantly higher levels of CRP, CRP/albumin, and NLR in patients hospitalized at the ICU and palliative care unit than the ward in our cohort seem to be in line with the association of these two hospital units with the higher in-hospital mortality rates. The present study also evaluated the predictive power of well-known inflammatory markers such as CRP and rather new used inflammatory markers such as NLR, CRP/albumin, PLT/MPV and PLR. Unlike other studies, in our study, the multivariate analysis included these inflammatory markers beside co-morbid diseases and reason for acute hospitalization diseases in the regression model. The potential utility of CRP and NLR in identification of poor prognosis in the ICU and palliative care unit seems also notable in this regard, given the importance of making quick and accurate decisions in the care for the seriously ill or frail patients in order to prioritize those with a high risk of mortality [19].

Our ROC analysis showed that the cut-off values of mortality with higher area under curve findings related to the prognostic role of CRP levels ≥ 44 mg/dl, NLR ≥ 7.75 and PLT/MPV ratio < 26.2 × 103 and CRP/albumin ≥ 13.5 in predicting increased in-hospital mortality risk and in discriminating non-survivors in very elderly hospitalized patients, emphasizing the potential utility of these prognostic markers in helping clinical decision making to optimize the coherence between targets of care and realistic clinical outcomes alongside health care resource utilization [20]. Consistent with our findings, elevated levels of CRP were reported to be associated with increased risks of frailty, overnight hospital admission and short-term all-cause mortality in the elderly population [14, 21]. Poredos et al. showed that increased circulating inflammatory markers in patients with superficial vein thrombosis could be a sign for presence of occlusion of veins [22]. The NLR was indicated to be an inexpensive and readily available biomarker that can help to identify individuals at risk of in-hospital complications and in-hospital mortality [10, 23]. Indeed, an NLR cut-off value of 5.0 was shown to predict the medium- to long-term mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome [10], while an NLR cut-off value of 7.35 was reported to identify 30-day mortality in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage [24]. The lower PLT/MPV ratio in non-survivors than in survivors in our cohort seems consistent with data from a past study on predictors of in-hospital mortality in 1556 ICU patients, which indicated an association of higher MPV and lower platelet count with a higher mortality rate [11].

The established role of higher CRP and low serum albumin levels as CRP to serum albumin ratio has a crucial role for predicting increased in-hospital mortality in our cohort, which seems notable given that hypoalbuminemia has been considered to offer strong prognostic information additional to usual prognostic variables for the prediction of in-hospital mortality in elderly patients admitted for acute cardiac conditions [25–27]. Past studies also reported the association of hypoalbuminemia with mortality and severity of pneumonia in hospitalized patients with community acquired pneumonia [28] and with mortality after oncological surgery among the elderly [29, 30]. Repeated microalbuminuria testing can be used for an early predictor of development of nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes rather than mortality in all age groups [31].

In this regard, the potential utility of NLR, CRP and PLT/MPV ratio in prediction of in-hospital mortality risk among very elderly patients seems also important given the simplicity, low cost, and availability of these inflammatory markers with a broad prognostic range across different clinical conditions including cardiovascular disease, malignancies, and infectious diseases [10, 32, 33].

A major strength of the current study is the comprehensive assessment of potential prognostic factors related to patient demographics, admission or co-morbid diagnosis, hospital units, inflammatory markers and other laboratory findings, as well as provision of data on cut-off values of inflammatory markers for discrimination of non-survivors from survivors in a relatively high number of very elderly patients hospitalized with heterogeneous diagnoses. However, certain limitations to this study should be considered. First, due to the retrospective single center design, establishing the temporality between cause and effect as well as generalizing our findings to overall very elderly hospitalized population seems difficult. Second, given that patient outcome in the elderly is also certainly affected by the patient frailty, lack of data on patient frailty is another limitation which otherwise would extend the knowledge achieved in the current study. Nevertheless, despite these certain limitations, given the paucity of solid information available in this area, our findings represent a valuable contribution to the literature

In conclusion, our findings revealed admission for very elderly patients especially over 90 years old having chronic renal failure co-morbidities and acute renal failure due to sepsis requiring intensive care unit and palliative care unit stay as well as NLR ≥ 7.75 significantly predict increased risk of in-hospital mortality among very elderly hospitalized patients. In addition, NLR ≥ 7.75 and also CRP levels ≥ 44 mg/dl, CRP/albumin ≥ 13.5 and PLT/MPV ratio < 26.2 × 103 levels can be used for estimation of high risk of in-hospital mortality among very elderly hospitalized patients. Very elderly patients are expected to have high risk of in-hospital mortality, but in those patients hospital mortality is about 13%. The estimation of high risk of mortality is important for the early approach and for this purpose NLR could be very helpful, like CRP/albumin and presence of renal failure. Our findings emphasize the importance of nutritional screening at hospital admission as well as the potential utility of inflammatory markers in aiding clinical decision making among very elderly hospitalized patients in terms of recognizing and predicting the prognostic outcome and identifying individuals for whom palliative care or targeted interventions and treatments are indicated.