Introduction

Thyroidectomy can lead to several complications, hypocalcaemia being one of them.

Hypocalcaemia due to parathyroid gland insufficiency can be caused by factors such as surgical injury causing devascularisation, inadvertent parathyroidectomy and haemodilution [1, 2].

Temporary hypocalcaemia occurs in 19% to 38% of patients after thyroidectomy, while 0% to 3% of patients develop permanent hypoparathyroidism [3].

Risk factors for hypocalcaemia after total thyroidectomy have been analysed.

Vitamin D level is one of the most investigated. It has a pleiotropic health effect [4–7]. Several studies have reported that preoperative vitamin D deficiency is a risk factor for postoperative hypocalcaemia [3, 8, 9]. Until now, mainly postoperative and perioperative calcium and vitamin D supplementation has been used to prevent postoperative hypocalcaemia [10–17]. Preoperative supplementation of calcium and vitamin D was used in only one study. It reduced the incidence of laboratory hypocalcaemia [18]. However, only 32.61% of 92 participants had multinodular goitre. The rest of the patients were ill with cancer or toxic goitre – conditions associated with higher frequency of postoperative hypocalcaemia [19].

The authors did not focus on a thorough analysis of laboratory assays (parathormone and calcium levels) or hypocalcaemic symptoms. Inactivated forms of vitamin D, used in the study with long time to onset of action, are unlikely to be beneficial in 24-hour preoperative supplementation [20]. In another retrospective study, perioperative calcium and calcitriol supplementation reduced laboratory and symptomatic hypocalcaemia more effectively than the postoperative supplementation [17]. However, only the efficacy of perioperative supplementation was evaluated in that study. The group of enrolled patients was not homogeneous – some of them had carcinoma and they additionally underwent lymphadenectomy.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of preoperative prophylactic oral supplementation of calcium carbonate and alfacalcidol on the prevention of postoperative hypocalcaemia in thyroidectomised nontoxic multinodular goitre (NTG) patients.

Material and methods

Patients

153 NTG patients were enrolled in this prospective single-blinded (for care providers) randomised controlled study. Total thyroidectomies with routine identification of the recurrent laryngeal nerves and parathyroid glands via a transverse cervicotomy under general anaesthesia were performed by 3 experienced surgeons at the Department of Surgery from April to December 2017. This study was performed with the informed consent of each patient. The approval of an appropriate local ethics committee (Bioethical Commission at the Medical University of Lodz – No. RNN/237/16/KE) was obtained.

In our study, the exclusion criteria were as follows: a history of preoperative oral calcium or vitamin D supplement use, receiving medications affecting serum calcium metabolism (i.e. antiresorptive agents, anabolic medicaments, thiazide-type diuretics, contraceptive drugs, hormone replacement therapy), metabolic bone disease, renal insufficiency, sarcoidosis, a history of prior thyroid or neck surgery or parathyroid diseases, prior neck radiation therapy, substernal thyroid disease, Graves’ disease, thyroid cancer, parathyroid autotransplantation.

Study design

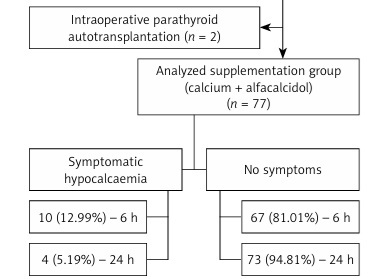

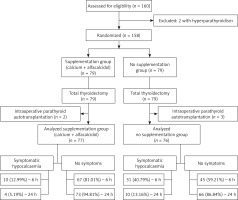

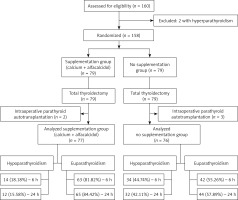

Preoperatively, the patients were randomly assigned (coin toss) to routinely receive (group B – 76 participants) or not to receive (group A – 77 participants) supplementation (Figures 1 and 2). All patients in the supplementation group were administered 3 g/day oral calcium carbonate (Teva Pharmaceuticals Polska Sp. z o.o, Warsaw, Poland), administered as 1 g every 8 h from 9 a.m., and 1 µg/day alfacalcidol (GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals S.A., Poznan, Poland), taken once on the day before surgery, and 1 g/day oral calcium carbonate taken once and 1 µg/day alfacalcidol taken once in the morning on the day of the operation. In the first 12 h after the procedure, the participants received intravenously 500 ml of crystalloid.

In both groups, participants who developed postoperative hypoparathyroidism (parathormone (iPTH) < 1.6 pmol/l at 6 or 24 h after surgery) or symptomatic hypocalcaemia during hospitalisation were treated with oral calcium (3 g/day – taken 1 g every 8 h) and vitamin D derivatives (1 µg/day alfacalcidol taken once). Intravenous calcium gluconate was administered if symptoms persisted despite oral supplementation. Patients with symptomatic hypocalcaemia received supplementation until the symptoms subsided. The treatment was extended to 6 weeks in patients with hypoparathyroidism on the day of discharge.

In both groups, anthropometric measurements and serum laboratory tests were performed on the day before surgery (Tables I and II).

Table I

Characteristics of included patients

Table II

Preoperative levels of various parameters among groups

[i] 25-OHD – 25-hydroxyvitamin D, iPTH – parathormone, ALP – alkaline phosphatase, P – phosphates, Alb – albumin, TSH – thyroid-stimulating hormone, fT3 – free triiodothyronine, fT4 – free thyroxine, SD – standard deviation, IQR– interquartile range. (1) Statistical significance was evaluated using Student’s t-test. (2) Statistical significance was evaluated using the Mann-Whitney test.

iPTH levels were measured with the electrochemiluminescence assay (ECLIA), and total calcium levels were determined with the colorimetric quantitative method (CA CALCIUM ARSENAZO III). Serum iPTH and total calcium levels were measured 6 and 24 h as well as 6 weeks postoperatively. The total serum calcium level was adjusted for the serum albumin level.

25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-OHD) levels were measured using the chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) (Architect 25-OHD).

All participants were clinically evaluated for symptoms of hypocalcaemia. Hypocalcaemic symptoms were categorized as mild (a tingling sensation and numbness of the hands or feet and perioral numbness) or severe (a positive Chvostek sign, Trousseau sign, tetany, and carpopedal spasms) [14].

Postoperative hypocalcaemia and severe hypocalcaemia were defined as corrected calcium levels 2.0 to 2.19 mmol/l and < 2.0 mmol/l, respectively, even if recorded in one measurement only.

Thresholds defining vitamin D status were determined on the basis of current guidelines [21]. The number of parathyroids found intraoperatively and noted in the histopathological examination protocol was also taken into consideration.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using a commercially available statistical software package (Statistica 13.1 for Windows; StatSoft Poland Ltd.).

Continuous variables were expressed as: mean ± SD, median and minimum–maximum values. The normal distribution was verified with the Shapiro-Wilk test. The data were compared for statistical analysis using Student’s t-test to evaluate differences between quantitative variables following a Gaussian distribution. Variables following a non-parametric distribution were compared with the Mann-Whitney test. Categorical data analysis was done using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test.

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was calculated to evaluate correlations between iPTH levels and corrected calcium levels due to the non-occurrence of normal distribution. Serum calcium levels were plotted over time and analysed using a general linear model for repeated measurements. A statistical significance threshold of α < 0.05 was used.

Results

Patients’ characteristics are summarised in Tables I and II.

Symptomatic hypocalcaemia

Mild hypocalcaemic symptoms from the beginning of hospitalisation to the end of the study developed in 41 (26.79%) participants after total thyroidectomy (Table III).

Table III

Comparison of symptomatic hypocalcaemia between two groups

Twenty-one (51.22%) participants with hypocalcaemic symptoms had calcium levels < 2.0 mmol, 18 (43.90%) patients had calcium levels in the range 2.0–2.19 mmol/l, and 2 (4.88%) participants had calcium levels within normal limits. Five (50%) of 10 patients with symptomatic hypocalcaemia in group B and 23 (74.19%) of 31 patients with symptoms in group A had postoperative hypoparathyroidism during hospital stay.

More participants in group A than in group B presented symptoms of hypocalcaemia during the study and at 6 h after surgery (Table III). It was observed in 31 (40.79%) patients in group A and in 10 (12.99%) in group B. It persisted in 10 (13.16%) and 4 (5.19%) participants in groups A and B at 24 h postoperatively, respectively. None of the participants developed symptomatic hypocalcaemia at 24 h postoperatively.

In patients with hypoparathyroidism, symptomatic hypocalcaemia occurred more frequently in group A than B, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.11) (Table III).

No participant had symptomatic hypocalcaemia 6 weeks after thyroidectomy.

Laboratory hypocalcaemia

Laboratory hypocalcaemia for group A and B during the study was found in 51 (67.11%) and 39 (50.65%) participants, respectively, which was statistically significant (Table IV).

Table IV

Comparison of laboratory hypocalcaemia between two groups

More patients in group A than in group B had laboratory hypocalcaemia during the study and at 6 and 24 h after surgery (Table IV).

In 80.95% of participants with postoperative hypocalcaemia at 6 h after surgery in group A and in 86.67% in group B, laboratory hypocalcaemia resolved within 6 weeks after surgery.

Twenty-nine (18.95%) patients had severe hypocalcaemia during the study. More patients in group A than in group B had severe hypocalcaemia during the whole study, hospitalisation and at 24 h postoperatively (p < 0.05) (Table IV).

Calcium levels

Calcium levels at 6 h after surgery were significantly lower in patients in group A compared to the remaining 77 patients in group B.

The difference was even more significant for calcium levels at 24 h postoperatively (Table V).

Table V

Comparison of serum test values (mean ± standard deviation) after total thyroidectomy between groups with and without oral calcium and vitamin D supplements

However, due to significant differences in postoperative hypoparathyroidism incidence between the two groups (18.18% vs. 46.05%; p < 0.05), propensity score matching was performed.

There were no statistically significant differences between groups in corrected calcium levels and their postoperative decreases (p = 0.06) in a general linear model for repeated measurements (Table V).

Hypoparathyroidism

Preoperative iPTH levels in group A were higher than in group B (Table II). Hypoparathyroidism was observed in 49 (32.03%) participants during the study and hospitalisation (Table VI). The correlation analysis showed a statistically significant, positive correlation between iPTH levels and corrected calcium levels at 6 h postoperatively (r = 0.27; p < 0.05) and a positive correlation between iPTH levels and corrected calcium levels at 24 h postoperatively (r = 0.45; p < 0.05).

Table VI

Comparison of hypoparathyroidism between two groups

More patients in group A than group B developed hypoparathyroidism during hospitalisation, during the study and at 6 and 24 h after surgery (Table VI).

Six weeks after surgery, 7 (9.21%) participants in group A and 2 (2.60%) participants in group B with low iPTH levels required oral calcium and vitamin D supplementation (p = 0.31). All those patients had hypoparathyroidism at 6 and 24 h postoperatively. During hospital stay, 10 (25.64%) participants with laboratory hypocalcaemia and 2 (28.57%) participants with severe laboratory hypocalcaemia in group B had hypoparathyroidism. In group A, 33 (67.35%) patients with laboratory hypocalcaemia and 17 (80.95%) patients with severe hypocalcaemia developed hypoparathyroidism.

25-hydroxyvitamin D

The mean preoperative 25-OHD level in the studied population was 17.85 ±5.11 ng/ml (range: 9.60–42.10 ng/ml). Normal 25-OHD levels (30–50 ng/ml) were observed in only 5 (3.27%) participants. 148 (96.73%) of 153 volunteers demonstrated 25-OHD levels that were lower than 30 ng/ml. 112 (73.20%) patients had 25-OHD levels of less than 20 ng/ml. Thirty-six (23.53%) volunteers had suboptimal levels of 25-OHD (20–30 ng/ml). 1.31% of adults revealed severe hypovitaminosis D (25-OHD levels lower than 10 ng/ml).

Upon performing propensity score matching, there were no statistically significant differences in the 25(OH)D level and 25(OH)D deficiency between groups A and B (p = 0.22; p = 0.05). The association between the change in the corrected calcium level and the vitamin D level was not statistically significant (p = 0.98).

Discussion

The rates of symptomatic hypocalcaemia in the supplemented and control groups in our study were in a range similar to other studies – 4.1%–40% with supplementation versus 4.5% to 44.4% without supplementation [10–15] (Table III).

Therefore, our data suggest that routine short-term preoperative oral calcium and vitamin D administration can significantly reduce the incidence of symptomatic hypocalcaemia after total thyroidectomy, although it does not completely eliminate its occurrence. Supplementation alleviated the severity of hypocalcaemia. In this study, only mild symptoms of hypocalcaemia were observed.

There was no difference between the severity of symptoms in the supplemented and control groups. That may be due to early supplementation as soon as symptoms appeared.

In our research, there was no significant difference in postoperative calcium levels between the groups. Serum calcium levels decreased in most of our patients early with the nadir at 6 h postoperatively. At 24 h postoperatively, serum corrected calcium levels began to recover. Interestingly, the lowest iPTH levels were measured at 24 h postoperatively (Table VII).

Table VII

Comparison of serum iPTH test values after total thyroidectomy between groups with and without oral calcium and vitamin D supplements

Haemodilution on the day of surgery may cause a decrease in calcium levels. Our results suggest that supplementation only before surgery is not enough to prevent postoperative hypocalcaemia. Although alfacalcidol was administered shortly before surgery (time to onset of action 1–2 days), calcium levels decreased at 6 h postoperatively and iPTH levels at 24 h postoperatively [20].

In contrast to our research, some researchers obtained significantly lower calcium levels in the non-supplementation group [10–12, 14, 22].

However, those results should be interpreted carefully given their substantial limitations because of the heterogeneity of the participants involved.

In our study, the investigated group was homogeneous. It consisted solely of people with NTG.

In the Alhefdhi et al. review, the authors performed the comparison of results of nine studies [22]. In studies comparing calcium and vitamin D versus no intervention, supplementation was administered postoperatively. Mean total calcium levels on postoperative days 1 and 2 were lower than in our study. Mean iPTH levels were also lower than mean iPTH values in our series.

In contrast, in the Jaan et al. study, calcium and vitamin D supplementation was started 7 days before surgery and continued postoperatively [15].

The mean calcium levels in the supplemented group were higher at 6 h postoperatively than in our research. That suggests a relationship between the duration of pre-surgical supplementation and the postoperative calcium level.

In another study, the preoperative calcium level was an independent protective factor for postoperative hypoparathyroidism. A 0.1 mmol/l higher calcium level was associated with a 68% lower risk of postoperative hypoparathyroidism [23]. Supplementation alone seems to reduce the incidence of hypoparathyroidism in our research. A correlation between calcium and PTH levels in the postoperative period was observed in our study. Furthermore, most studies included in the Edafe et al. review of the predictors of post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia found that lower postoperative PTH levels from 30 min to 5 days after surgery were associated with transient hypocalcaemia [3]. That relationship was independent of preoperative 25-hydroxyvitamin D and postoperative calcium levels. In most studies, laboratory hypocalcaemia was defined as ‘serum calcium concentrations of < 8.0 mg/dl (2 mmol/l), even if only in a single measurement’ [10–12, 14]. That term corresponds to the definition of severe hypocalcaemia adopted in our study.

The rate of severe hypocalcaemia in our study was similar to rates of laboratory hypocalcaemia in other studies [10–12, 14].

However, according to our data, 43.90% of participants with symptoms had calcium levels in the range of 2.19–2.0 mmol/l. The finding suggests that even patients with slightly reduced calcium levels should be carefully monitored for the development of symptomatic hypocalcaemia. Interestingly, hypoparathyroidism was present in 68.29% of symptomatic patients. Only 48.86% of patients with laboratory hypocalcaemia and 67.86% with severe hypocalcaemia during hospitalisation had hypoparathyroidism. These findings question the absolute value of postoperative iPTH levels in predicting hypocalcaemia and its symptoms [24].

Our results also demonstrated widespread vitamin D deficiency in surgical patients (73.20%). Data similar to our research were reported in Poland. About 70% of subjects in the Lodz province and in Poland were vitamin D-deficient [25–27].

However, in our study the preoperative 25-OHD level was not a risk factor for the development of postoperative hypocalcaemia. Only some of the previous studies found no relationship between preoperative vitamin D levels and postoperative hypocalcaemia findings [16, 28, 29].

Both perioperative calcium and vitamin D supplementation have been previously proposed to prevent hypocalcaemia after total thyroidectomy [10–16].

To the best of our knowledge, this is a pioneering study assessing the usefulness of preventive calcium and alfacalcidol supplementation before thyroidectomy in patients with NTG. The study was not burdensome for patients, because they did not have to take medications before being admitted to hospital. As researchers, we did not have to rely on patient compliance after hospital discharge. The patients took drugs only during the hospital stay.

A major limitation of our study was the moderate sample size.

In conclusion, preoperative calcium and vitamin D supplementation effectively reduced the incidence and severity of hypocalcaemia after total thyroidectomy in NTG patients.

That might increase patients’ safety and satisfaction. Despite the use of supplementation, thyroidectomised patients should be carefully monitored for the development of symptomatic hypocalcaemia. The use of only preoperative supplementation does not exempt clinicians from performing laboratory tests for calcium and iPTH in the postoperative period. Preoperative supplementation does not prevent hypocalcaemia in all patients. The main disadvantage of the study was short-term calcium and alfacalcidol supplementation prior to surgery. It resulted from the fact that in our department, surgeons do not prepare all patients themselves for surgery. It was a factor impossible to circumvent during the course of the study.