Introduction

From the environmental-medicine and public-health perspective, allergies constitute a significant problem [1–8]. The highly prevalent allergic rhinitis (AR), defined as “a clinically overt nasal disorder, which develops as a response to allergen exposure and takes the form of IgE-mediated inflammation of the nasal mucosa” [9], results in a lower quality of life, contributes to sleep disturbances, and lowers productivity at work and at school. The conditions that commonly accompany AR (such as conjunctivitis, otitis, sinusitis, or bronchial asthma) generate additional healthcare costs (including direct, indirect, and non-measurable costs) [1, 10]. The data above indicate a definite need to implement systemic solutions, such as an integrated healthcare system, in order to improve the quality of care at all levels of interaction with allergic patients. Coordinated healthcare should put a particular emphasis on preventive rather than corrective measures as the strategy of care designated for patients with lifestyle diseases.

The purpose of our study was to assess the proportion of patients diagnosed with perennial allergic rhinitis (PAR) who could benefit from the solutions adopted in the chain of services offered by coordinated healthcare.

According to the definition of the European Office for Integrated Health Care, which is part of the World Health Organization (WHO), coordinated care “is the concept of services related to the diagnosis, treatment, care, rehabilitation, and promotion of health in the field of financial resources, implementation and organization of health services and management”. For the Polish Association of Managed Care, Coordinated Health Protection (CHP) means organized activities of system participants aimed at achieving high cost effectiveness of services, quality of medical care, and continuity of patient service [11]. The recently implemented concept of a hospital network is intended to help ensure the provision of healthcare services and improve the quality, safety, and accessibility of highly specialized healthcare. This is being implemented by adopting and meeting transparent criteria (including establishing the cost of, and pricing, health services as well as setting the guidelines for cost accounting by the Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariffs (AOTMiT) based on healthcare-need maps).

Material and methods

This study was conducted in 2 stages:

– stage I – questionnaire-based survey (18,617 respondents) conducted via Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) with the use of a personal digital assistant (PDA);

– stage II – complementary examination (4783 patients) of a subgroup of stage I respondents who underwent a medical examination (Table I). This subgroup was selected randomly, based on their Polish citizen identification numbers (PESEL numbers) being drawn randomly by the Ministry of Interior and Administration. The study was part of research project No. 6 PO5 2005 C/06572 “Implementation of the system for the prevention and early detection of allergies in Poland” (Epidemiology of Allergic Diseases in Poland, ECAP) commissioned by the Minister of Health, and was a continuation of the international studies European Community Respiratory Health Survey II (ECRHS II) [12] and International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) [13] adapted for Central and Eastern Europe. The cross-sectional study was conducted in a population of Polish respondents, who were residents of one of eight metropolitan areas (Gdansk, Wroclaw, Poznan, Katowice, Krakow, Lublin, Bialystok, Warszawa) or a rural area (Zamosc and Krasnystaw counties).

Table I

Study group characteristics. A – Respondents included in the first and second stage of the questionnaire-based study. B – Respondents with physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis (stage II of the study)

A

B

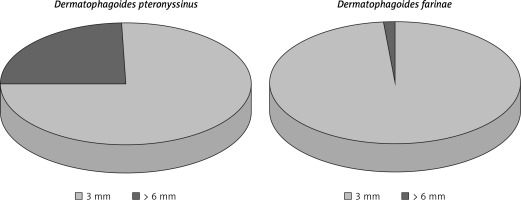

For analysis, study results were stratified by respondent age (6–7 years, 13–14 years, adults) and clinical diagnosis (AR, seasonal AR (SAR), and PAR). According to the diagnostic criteria for AR included in Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines [1, 10], nearly 23% of all respondents had AR. Out of all those diagnosed with AR, 14% had SAR and 15% had PAR. The study population comprised mostly females and metropolitan-area residents. Among the all-year allergens assessed in skin-prick tests, the one predominantly responsible for patients’ symptoms was Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus especially in comparison with Dermatophagoides farinae (Figure 1). Interestingly, positive skin-prick test results were most commonly due to house dust mites rather than grass or tree pollens. As dictated by the stages of the study, data analyses were done separately for certain items from the questionnaires: the responses given at the first and second stages of the study that had been verified by medical history and examination, including skin-prick testing (Allergopharma) (birch; grasses/cereals; wormwood; Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae; moulds (group I): Botrytis cinerea, Cladosporium herbarum, Alternaria tenuis, Curvularia lunata, Fusarium moniliforme, Helminthosporium; and moulds (group II): Aspergillus fumigatus, Mucor mucedo, Penicillium notatum, Pullularia pullulans, Rhizopus nigricans, Serpula lacrymans; dog; cat; hazel; alder; rye; ribleaf; Cladosporium herbarum; Alternaria tenuis) with negative and positive (histamine) controls; spirometry, and peak nasal inspiratory flow (PNIF) test.

Figure 1

Proportion of positive responses to house dust mites in skin-prick tests in the study population (stage II of the study). Source: own

This study had been approved by the Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of Warsaw (KB/206/2005) and the Inspector General for the Protection of Personal Data. Statistical analysis was performed with the use of the prop.test function (i.e. a test for equality of proportions) and contingency tables. The odds ratios (OR) for the use of various prevention measures in individual groups of patients were calculated based on a logistic regression model.

The basic catalysts as the mechanisms of change required for the introduction of coordinated health protection are as follows:

Ensuring external conditions – political will and appropriate political and executive decisions at the level of the Ministry of Health (MH), and further contracting them by the National Health Fund (NHF).

Money – grants from the European Union (EU) and loans from the World Bank (WB) and others.

Support and knowledge – which is created/shaped by giving appropriate program directions to the Ministry of Health (MH), voivodships, powiats, and relevant technical guidelines for restructuring and other projects – support from scientists, the World Bank, and others. Coordinated patient care as a disease management has become one of the main topics of discussion in the Polish health care system. The experience drawn from international practices helped to create, for example, a basis for the process of coordinated care in oncology in Poland [14]. The pilot Primary Health Care PLUS model has been tested in Poland since July 2018 and is in line with the “Strategy for the development of primary health care applicable in the field of primary health care” developed by the Ministry of Health. The scope of the Primary Health Care (PHC) includes: first-line care and triage; diagnostic services; therapeutic services together with health check; preventive services and health promotion; and mother and child and reproductive health. There is also a trend of expanding the scope of tasks in primary care, with greater involvement in screening, prevention, and health promotion [15].

There is also extensive research showing the various elements and definitions of coordinated care and revealing different perspectives that affect the design and shape of this process. Coordinated care is not a result but an important factor in improving the quality of health care [16]. Therefore, coordinated care is also an important factor in improving the quality and efficiency of healthcare, for the chronically allergologically ill patient in Poland. We could reach this through organizational restructuring and the implementation of a new model of paying service providers. The activities undertaken are to ensure good management of diagnostics, therapy, and rehabilitation, and to orientate them to the needs of the patient.

Coordinated healthcare in Poland should result in the following [17]:

– Increased patient satisfaction;

– Better quality of care;

– Implementation of care with patient-centred care;

– Increased effectiveness of preventive health care: primary (first phase), secondary (2nd phase), and 3rd phase;

– Optimization of the diagnostic and therapeutic process, which is expressed in the application of accurate measures aimed at achieving results in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases;

– Cooperation of health care personnel during the provision of services;

– Improvement of cost effectiveness in the field of diagnostics and treatment.

This means that designing and implementing a coordinated health protection mechanism should include the following stages of implementation: 1) planning, 2) implementation, 3) financing, 4) monitoring, and 5) Evaluation [18].

Stage 1. planning:

– goals should be defined at the stage of coordinated healthcare planning. identify and acquire qualified and committed specialists adequately representing individual medical professions in organizations that have been invited to cooperate; establish transparent organizational structures;

– identify and attract all stakeholders involved at each stage of the process; carry out in-depth analysis and assessment of needs;

– identify possible solutions;

– elaborate a project card taking into account elements such as: initial context, methods, data, measures of results, databases, division of roles, project structures (steering committee, project group/groups), schedule with nodal terms and project phases (so-called “milestones”), and implementation guidelines;

– evaluation and monitoring process, aspects related to ethics, literature on the subject;

– prepare an action plan and comprehensive evaluation.

Stage 2. implementation:

– involve the participants and start implementation;

– raise awareness and disseminate project goals;

manage the implementation process.

Stage 3. financing:

Stage 4. monitoring:

Stage 5. evaluation:

Results

The most commonly used forms of secondary prevention in the group of patients diagnosed with AR were, in descending order of frequency, mattress protectors and anti-dust-mite spray. A relatively large proportion of allergic respondents removed carpets from their rooms and bedrooms. These carpets had frequently been more than 5 years old. Nearly 20% of those diagnosed with PAR used targeted anti-dust-mite prevention measures; this proportion in the healthy controls was 13% (p < 0.001).

In the group with self-reported AR (Table II–V), the proportion of urban residents who removed carpets from their homes was higher (20%) than the proportion of rural residents (14%) who used this preventive measure (p = 0.01). An analogously higher proportion of urban residents removed carpets from their bedrooms (19%) in comparison with the proportion of rural residents (13%) who used this preventive measure (p = 0.02). Among the respondents with higher education, those who removed carpets from their homes was 23%, which was a considerably higher figure than that for respondents with secondary education (19%) (p = 0.0002). Mattress protectors were more likely to be used by respondents with higher education (7%) than those with lower levels of education (4–6%) (p = 0.008). Annual net income was another factor that determined significant differences between the study groups. Respondents from the group with the highest net income (> 16,000 PLN) were more likely to remove carpets from their rooms (26%) in comparison to those with lower net income (15–20%) (p = 0.0005). An analogously higher proportion of respondents with the highest net income removed carpets from their bedrooms (24%) in comparison to the proportion of respondents with other (lower) net incomes who used this prevention measure (14–18%) (p = 0.001).

Table II

Selected methods of limiting the house dust mite population (stage I of the study)

Table III

Selected methods of limiting the house dust mite population (stage II of the study)

Table IV

Selected methods of limiting the house dust mite population in respondents with physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis (positive history and skin-prick test) (stage II of the study)

Table V

House dust mite prevention: A – Respondents with self-reported allergic rhinitis stratified by sex, level of education, area of residence, and economic status, B – Respondents with physician-diagnosed seasonal allergic rhinitis stratified by sex, level of education, area of residence, and economic status, C – Respondents with physician-diagnosed perennial allergic rhinitis stratified by sex, level of education, area of residence, and economic status, D – The control group stratified by sex, level of education, area of residence, and economic status

A

B

C

D

In the group of patients with physician-diagnosed PAR (Table V C), males constituted a higher proportion of patients who bought new carpets for their bedrooms (nearly 11%) in comparison to the proportion of women (9%) who used this allergy prevention measure (p = 0.04). Patients with higher education were decidedly more likely to remove carpets from their room (23%) than those with either elementary (8%) or secondary education (18%) (p = 0.02). Moreover, the proportion of patients with higher education who removed carpets from their bedrooms was also significantly higher than the proportion of patients with other levels of education who used this allergy prevention measure (p = 0.01). The data presented in Table III suggest that patients with AR were more likely to remove carpets from their bedrooms (as an allergy prevention measure) than the control group. The use of anti-dust-mite spray showed a similar predilection, with this prevention measure more commonly used by patients with PAR (OR = 1.71) than by healthy controls (OR = 0.68).

Table VI

Areas and components in the framework of coordinating health care for a patient suffering from chronic allergies in Poland – our proposal

[i] Source: adopted based on the guidelines for “Organization of patient care with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Denmark” from the World Bank. World Bank database. [Online]. Quoted in 2017. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/.

Patients allergic to Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (wheal diameter ≥ 3 mm) were more likely to remove carpets from their homes (OR = 1.34; p = 0.001) and bedrooms (OR = 1.43; p = 0.0001) and to use anti-dust-mite spray (OR = 1.63; p = 0.0006) than non-allergic individuals. Patients allergic to Dermatophagoides farinae (wheal diameter ≥ 3 mm) were also more likely to remove carpets from their homes (OR = 1.33; p = 0.002) and bedrooms (OR = 1.45; p = 0.0001) than individuals from the control group.

Coordinated healthcare involves offering comprehensive services at any given level of healthcare (i.e. horizontal aspect) as well as across all levels of the structural hierarchy of healthcare: primary care, outpatient specialist care, hospital treatment (i.e. vertical aspect) in conjunction with the following 4 principles: accessibility, comprehensiveness, early initiation, and continuity of the diagnostic and therapeutic processes [19].

In the implementation of the above-mentioned principles of continuous improvement, cooperation, and rationality of dealing with a chronically ill allergologically patient at Warsaw Medical University, we have been preparing a proposal for general organizational standards. We postulate the possibility of using the concept of coordinated health care, e.g. through organizational standards to improve the care of patients with perennial allergic rhinitis, which could be useful for any organizations specialised in the diagnostics and treatment process of patients with chronic allergies.

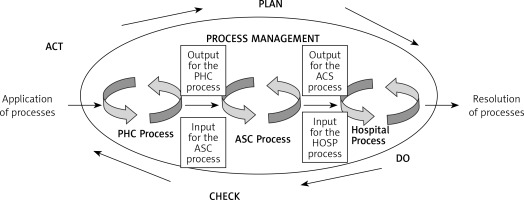

Figure 2 presents a model of management in diagnostic-therapeutic-rehabilitation processes during a health service for a patient chronically ill with allergic diseases. The Deming cycle was used in the design of the model, according to the logic of which the action plan in the process system should be ensured by performing, checking, and possibly making corrections, so that the provision of the service to the patient is realized for his/her needs.

Figure 2

Model of management of diagnostic, therapeutic, and rehabilitation processes during the implementation of a health service according to the logic of the Deming cycle. Source: own study based on Lisiecka-Biełanowicz M. Quality of value relationships in the process of providing services in health care organizations. In: Ergonomia Niepełnosprawnym. In the age of nanotechnology and health care. Lewandowski J, Lecewicz-Bartoszewska J. (eds.). Monografie, ISSN 978-83-7283-212, Wyd. Lodz University of Technology, Łódź 2006; 201

PHC – primary health care, ASC – ambulatory specialist care/specialistic treatment outpatient centres, HOSP – hospital = care requiring hospitalization and treatment in a hospital.

The organization of care for a patient suffering from chronic allergies, including chronic nasal disorders, should, according to the guidelines, cover the following areas: identification of the patient group, care, self-monitoring by the patient, care organization, division of tasks, quality monitoring, implementation [18]. We should start from primary health care to define the area as well as components of coordinated health care for patients suffering from chronic allergies; our proposal is outlined in Table VI. After that we should start to include the following into coordinated health care for patients suffering from chronic allergies: ambulatory specialist care and care requiring hospitalization/treatment in a hospital.

Discussion

AR considerably worsens the patients’ quality of life because the pathomechanism of this condition involves nasal congestion. Due to its function in warming, filtering, and humidifying the inhaled air, the nose plays an important role in respiration physiology. Nasal passage occlusion, which is a key factor in AR, has several consequences, including frequent infections, sinusitis, otitis, sleep disturbances, and hypertension, all of which considerably lower the quality of life. In comparison with conditions such as hypertension or diabetes mellitus, AR lowers the quality of life much more. Nearly 40% of AR cases are associated with plant pollen allergies, whereas 1–13% of cases can be classified as PAR [2, 8]. The largest proportions of positive skin-prick test results in the Polish population were due to the following allergens: Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (23.4%); grasses (21.3%); wormwood (16.1%); trees such as birch (14.9%), hazel, and alder (11% each); and cat (12.8%) [2]. As a result of the common pathomechanism of inflammatory reaction in the upper and lower respiratory tract, the effect of nasal mucosal inflammation on the bronchi is of social and epidemiological importance. ARIA guidelines indicate that patients with symptomatic chronic rhinitis should be diagnosed for possible bronchial asthma, and – vice versa – patients with bronchial asthma should be diagnosed for rhinitis [1, 10]. The ECAP study estimated the risk of allergic asthma developing in patients allergic to the following environmental agents: Dermatophagoides farinae (OR = 7.7), cat (OR = 7.4), and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (OR = 7.1) [20]. Moreover, that study showed AR to be the strongest risk factor for the development of bronchial asthma (OR = 0.9) [21].

From a health economic perspective, AR undoubtedly generates a fair amount of indirect costs (which are difficult to measure) as well as direct costs. A 2008 Swedish study indicated that 37% of the study population reported at least 1 day of absence from work due to the troublesome symptoms of AR. The mean employee productivity loss due to absence from work (absenteeism), attending work despite being unwell (presenteeism), or taking care of a child affected with AR was 5.1 days over a period of 1 year. As a result, the mean productivity decreased by nearly 22%. The cumulative yearly cost of this decrease in productivity was 653 euros per employee (absenteeism: €286; presenteeism: €242; attending to a sick child: €124). The total value of all estimated indirect costs associated with AR and common colds exceeded €2.7 billion per year; 44% of those costs were due to absenteeism, 37% were due to presenteeism, and 19% to attending to an AR-affected family member [22].

Reducing work absence by 1 day per AR patient was shown to save €528 million or 20% of all costs [16]. In 2002, the total AR-associated costs in Germany were €1543 (of which indirect costs constituted 50%) [22]. According to studies conducted in the period 1999–2000, the proportion of indirect costs increased from 7% to 25% [16, 23]. Vandenplas et al., who evaluated AR patients in the period 2000–2007, observed that 79.2% of patients develop symptoms preventing a satisfying professional life, although the extent of difficulties posed by AR was not clearly defined [23]. A 2003 study by Hellgren et al. demonstrated that AR-associated indirect costs in the United States range from 0.1 to 9.7 billion USD, with mean indirect costs of 593 USD per AR-affected employee. For comparison, indirect costs of asthma are 85 USD (data for the year 2003) [22]. There are no available reports presenting the indirect costs of AR in Poland. This situation warrants a discussion on developing a standardized tool for reporting the effects of AR.

Contrary to the previous hypothesis calling for reduced allergen exposure, the currently discussed model of allergy prevention leans towards creating tolerance to the allergen [24, 25]. Primary prevention is intended to prevent the development of diseases, secondary prevention aims to limit disease progression, and tertiary prevention involves reducing disease-associated symptoms. Relevant literature contains no definitive, strong scientific evidence supporting the effectiveness of preventive measures in house-dust-mite allergies [1, 10]. One exception is the population of patients whose medical history is positive for a genetic factor and concomitant bronchial asthma. The use of chemicals to neutralize house dust mites is not recommended due to the non-specific reaction of the body to some of the ingredients of these chemicals. The experts who composed the international ARIA report recommend introducing integrated environmental control systems. In 2006, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) together with the World Health Organization (WHO) established the Global Alliance Against Chronic Respiratory Diseases (GARD) in order to improve the health status in populations affected by chronic diseases. The GARD strategy involves mainly implementing preventive measures at the local and global scale, while taking into account similarities between chronic conditions [26]. The GARD strategy is implemented in stages (stage 1 – a needs analysis, determining the goal and plan of action; stage 2 – creating and adopting healthcare policies; and stage 3 – long-term implementation). This strategy provides opportunities for evaluation at each stage until the predetermined goals are met [23, 24, 26, 27]. An integral part of the GARD program is the Polish National Health Program (“Assessing, elaborating, and raising awareness of risk factors for allergies and asthma, with a particular emphasis on air-borne allergens”) conducted by Raciborski et al. [28], which addresses the needs of patients with chronic respiratory diseases.

Efficient and effective management of the diagnostics and treatment of patients with chronic allergies may be achieved through coordinated healthcare ideas or conception. “(…) Coordinated healthcare conception involves a network of mutually cooperating healthcare providers (outpatient clinics, hospitals), with the access to these networks managed by treatment coordinators. These coordinators allocate funds, thus managing the financial aspect of medical services and arrange patients’ access to those services. Moreover, coordinators regulate patients’ healthcare, ensure treatment continuity, and oversee the quality of the treatment process. Coordinators, who are physicians, are to monitor the scheduling accuracy and high quality of medical services at each stage of treatment. The fundamental difference in the goals of this novel, coordinated healthcare involves a shift in emphasis from maximizing the number of provided services to maximizing their effectiveness, by adopting a process-oriented approach. The entire system involves an input in the form of patient needs and an output in the form of patient welfare and satisfaction. Between the starting point and the end of this system lies a “chain” of interconnected processes and sub-processes, involving various entities, such as pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, pharmacies, medical equipment suppliers (…)” [29].

Chronically ill patients (including allergy patients) undergo diagnostic and therapeutic processes, which are divided into sub-processes, all of which are part of the Polish National Healthcare Program (NPZ). “The goal of the NPZ for the period 2016–2020 is prolonging a healthy lifespan, improving public health and the associated quality of life, and reducing the impact of social inequalities on health” [30].

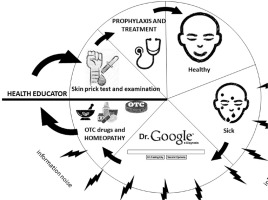

Coordinated healthcare requires the establishment of a specific treatment pathway for chronic allergy patients. Irrespective of whether the patient requires primary care, specialist care, or temporary hospital treatment (or would later require rehabilitation and a stay at a sanatorium intended for the treatment of chronic conditions, including chronic respiratory allergy), he or she is also going to receive support from a specially appointed health educator (HE) throughout the entire process of diagnosis and treatment.

The role of the HE would involve maintaining the desired relations with the patient, including the type of communication and organization of care to ensure that the chronically allergic patients are provided with all the services ordered by their physician at the scheduled time at the given stage of treatment and that these services meet suitably high standards (Figure 3). The treatment process under coordinated healthcare should be effectively monitored and supervised, which would positively affect the course of comprehensive patient treatment as well as its long-term outcomes. The role of an HE comprises an integral part of integrated healthcare in this era of globalization and digitalization. One very dangerous measure undertaken by the patients themselves is the so-called self-treatment, by using over-the-counter (OTC) medications [31], homeopathy [32], and obtaining medical information from unreliable Internet sources [33].

Figure 3

A wheel illustrating the suggested solutions that enhance the effectiveness of actions undertaken for the benefit of patients with allergies. Source: own

In conclusion, the proportion of patients diagnosed with a dust-mite allergy who undertook preventive measures against perennial allergic rhinitis was relatively low. Improving the fate of the Polish patient within the healthcare system requires an urgent implementation of actions, mainly educational in nature, addressed to patients across all levels of education, qualifications, and areas of residence. The quality of the relationship between healthcare professionals and patients with chronic allergies depends on compromises and experiential exchange, which helps build, maintain, and constantly strengthen relations with these patients, at the same time enabling them to share the responsibility for their health and wellbeing. This way of shaping the relationship between healthcare professionals and chronic allergy patients may shift the character of future healthcare services towards prevention, with the patients eager to play an active part in the process.