Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a chronic disease that affects all spheres of the patient’s life. If it is diagnosed, lifelong treatment is required.

Therapeutic decisions must be individualized and include the patient in the process of medical intervention. Proper treatment of the patient prevents bone fractures and deterioration of the skeletal system functioning. In the course of the disease, the microarchitecture is disturbed and bone mineral density decreases, resulting in a higher risk of low-energy fractures. As a consequence, the limited range of limb motion and chronic pain (lasting even longer than 1 year) may interfere with activities of daily living [1]. High costs of treatment and hospitalization make postmenopausal osteoporosis one of the main problems of public health in the 21st century [2]. Usually, in the case of treatment of a specific disease, emphasis is placed on pharmacotherapy and rehabilitation, whereas the mental health of the patient is quite often neglected. Considering the increasing life expectancy, patients are forced to struggle with osteoporosis for many years [3].

According to estimates from Eurostat, the demographic aging of the European population will be faster and faster after 2035. As a result, in 2060 Poland will have one of the oldest populations (the second oldest after Slovakia) in the entire European Union [4]. According to Janiszewska et al., in Europe postmenopausal women constitute one third of all patients diagnosed with osteoporosis, and the risk of the disease developing in females increases in direct proportion to age and doubles with each decade after the age of 65 years [5].

The patient’s subjective assessment of his/her life situation largely depends on both the physical and mental health condition. According to Juczyński, “the assessment of life satisfaction is the result of comparing one’s own situation with the standards they set. If the result of the comparison is satisfactory, it results in a feeling of satisfaction” [6]. The concept of life satisfaction is closely related to the concept of quality of life [7].

Increasingly, the term quality of life is used as a “measure” of life satisfaction. Life satisfaction and happiness are indicators of subjective well-being that constitute the main dimensions of mental health. Two methods of assessing life satisfaction are distinguished, i.e., global and specific for a specific area of life, e.g., work or family. The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) is a global measure of satisfaction with life. An assessment based on SWLS reflects the feeling of satisfaction with one’s own achievements and living conditions. Each person perceives life satisfaction individually, i.e., assesses it subjectively based on personal criteria and one’s own life experiences. There are few studies evaluating life satisfaction in people with osteoporosis. On the other hand, the quality of health is measured by general questionnaires such as SF-36 and EQ-5D, which can be used for various diseases. Detailed questionnaires, e.g., QUALEFFO-41, OQLQ, OPAQ, OPTQoL, ECOS-16, OFDQ, QUALIOST, JOQOL, are applied to assess the quality of life in patients with osteoporosis. One of the most commonly used is the Qualeffo-41 scale, which has been validated and translated into several languages including Polish and Korean [8, 9]. Initially, this scale was used in patients with osteoporosis with vertebral fractures, then, due to its universal nature, it was also used in patients with low bone mineral density measured in the lumbar spine, with and without vertebral fractures [10]. Mental health is one of the determinants of the quality of life in the elderly; therefore it is justified to conduct research among this growing group of the population [11].

The aim of our study was to assess whether the duration of postmenopausal osteoporosis in women affects their quality of life and satisfaction.

Material and methods

In the period from June 2018 to May 2019, the women were examined in two osteoporosis treatment clinics in Lodz. At the very beginning, 240 people took part in the survey. Following the recruitment procedure in which incorrectly completed questionnaires were rejected, 198 women were eventually qualified for the study. All the subjects who appeared for an appointment in the clinic’s waiting room were provided with brochures including information on the purpose and the course of the survey. Those who agreed to participate in the study were individually interviewed in a separate room where they confirmed their informed consent to participate in the study and filled out questionnaires (at the same time they also had an opportunity to ask the researcher questions). Then, the medical records of the respondents were analyzed and the patients who had a history of disease diagnosed according to ICD-10 – M81.0 – postmenopausal osteoporosis (the main criterion of eligibility) were deliberately selected. The other inclusion criteria were: informed consent to participate in the study and fully completed SWLS and QUALEFFO-41 questionnaires. Women with active neoplastic disease, malignant bone metastases, secondary osteoporosis, currently broken bones, receiving glucocorticoid therapy and hospitalized within the preceding 6 months were excluded from the study.

The research method is a quality of life survey and the following tools were applied:

An original questionnaire referring to socio-demographic data (including age, marital status, place of residence, financial situation).

The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS), developed by Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin in 1985, was used in the Polish version adapted by Zygfryd Juczyński; it provides information on subjective sense of satisfaction with life [6].

The SWLS scale includes the following five statements: 1. In many ways my life is close to an ideal; 2. The conditions of my life are perfect; 3. I am satisfied with my life; 4. So far I have achieved the important things that I wanted in my life; 5. If I could live my life again, I would not change anything; the respondent indicates one digit from 1 to 7 for each statement.

The numbers mean: 1 – I strongly disagree; 2 – I disagree; 3 – I slightly disagree; 4 – I neither agree nor disagree; 5 – I slightly agree; 6 – I agree; 7 – I strongly agree.

The possible result ranges between 5 and 35 points; the higher the score, the greater the sense of satisfaction with life. Using the scale, the respondents assess to what extent each statement relates to their existing life. After summing up all the points, the obtained result is interpreted according to the SWLS scale as follows: 31–35 points – very satisfied; 26–30 points – satisfied; 21–25 points – slightly satisfied; 20 points – neutral; 15–19 points – slightly dissatisfied; 10–14 points – dissatisfied; 5–9 points – extremely dissatisfied.

The final result is interpreted based on a sten scale. Values from 1 to 4 sten (SWLS: 5-17 points) are regarded as a low level of life satisfaction, 5–6 sten (SWLS: 18–23 points) as moderate, and within the range of 7–10 sten (SWLS 24–35 point) as a high level of satisfaction.

3. The quality of life was assessed based on the Polish version of a detailed questionnaire, QUALEFFO-41, which consists of 41 questions. It is divided into five main domains: pain (5 questions), physical functions (17 questions), social functions (7 questions), general health perception (3 questions) and mental functions (9 questions). The analysis of the result was carried out in accordance with the algorithm proposed by the International Osteoporosis Foundation, applying a scale from 0 to 100. The questionnaire results were interpreted according to the principle that the higher the number of points was, the worse was the quality of life. When completing the questionnaire, the subjects were asked to choose only one answer for each question. The results of each domain and the total QUALEFFO-41 score were analyzed.

Ethics

The study was voluntary and was conducted in accordance with the principles of human research specified in the Declaration of Helsinki. The respondents signed an informed consent form and were advised that the study would be anonymous, in accordance with the applicable regulations and the provisions of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The study was given a positive opinion from the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Lodz (Resolution No. RNN/215/18KE of June 12, 2018).

Statistical analysis

The results obtained from the questionnaires were statistically analyzed. The values of the analyzed parameters were presented as the mean with the standard deviation and as the median with the interquartile range (IQR). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test the normality of the distribution of the quantitative variable. Correlation coefficients between quantitative variables were calculated using the Spearman correlation. Comparisons between the groups were made using the Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA test. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13 Dell Inc. (StatSoft, Poland).

Results

One hundred ninety-eight women with postmenopausal osteoporosis were qualified for the study. The mean age of the respondents was 72.3 ±8.59 years (range: 51–90 years), the mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.71 ±4.73 kg/m2. The average age at the time of diagnosis was 61.82 ±9.74 years (range: 43–81 years). The average duration of osteoporosis among the respondents was 10.70 ±8.53 years. Among the subjects, 47% were married and 36% were widows. More than half of the study participants lived in a city with over 100 000 inhabitants, and only 9% in rural areas. The detailed characteristics of the study group are presented in Table I.

Table I

Characteristics of the study group

SWLS results

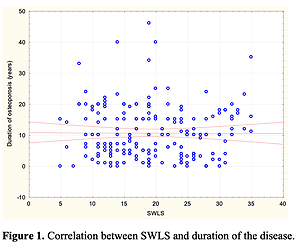

The mean result of the level of satisfaction with life assessed using the SWLS scale in the study group was 19.37 ±7.31 points (Table II). After conversion to sten units, the value was 5.0, which proves that satisfaction with life among the study participants was average. Following an analysis of the results obtained using Spearman’s rank correlation test, it was found that the duration of the disease (time from the diagnosis of osteoporosis to the day of the survey) has a statistically significant impact on life satisfaction (p = 0.0317, R = –0.1991) (Figure 1).

Table II

Descriptive statistics for the SWLS scale

| SWLS – scores | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Median | Lower quartile | Upper quartile | Sten |

| 198 | 19.37 | 7.31 | 19.00 | 13.0 | 25.0 | 5.0 |

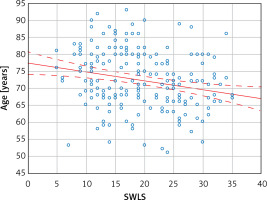

By comparing the mean SWLS results depending on the duration of the disease (Table III), it was shown that the lowest level of life satisfaction was observed in women who had suffered from osteoporosis from 6 to 10 years. On the other hand, the highest sense of satisfaction with life in the study group was observed among those who had lived with the disease longer than 16 years. Despite the noticeable differences in the point values of the SWLS scale, the results were not statistically significant and remained at the same level. The analysis of socio-demographic factors showed that age and education had a statistically significant impact on life satisfaction (Table IV). Life satisfaction was higher in older women as compared to younger subjects: R = –0.2245 (Figure 2).

Table III

SWLS and duration of osteoporosis

Table IV

Comparison of SWLS and QUALEFFO-41 depending on selected sociological and demographic parameters

QUALEFFO-41 results

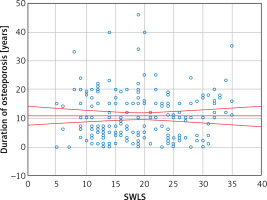

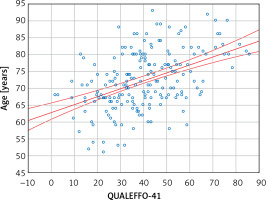

The study participants assessed their quality of life as moderate and obtained 40.26 ±16.92 points according to the QUALEFFO-41 scale (Table V). The quality of life deteriorated in women with a longer duration of the disease (p = 0.1213) (Table VI). Age, education and marital status had a statistically significant impact on the quality of life (Table IV). The quality of life in the respondents deteriorated with age: R = 0.4726 (Figure 3).

Table V

Descriptive statistics for the QUALEFFO-41 scale

| QUALEFFO-41 scores | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Median | Lower quartile | Upper quartile |

| 198 | 40.26 | 16.92 | 39.00 | 28.04 | 51.22 |

Discussion

The aging of Polish society poses a serious challenge to the mental health of an individual. Janiszewska et al. emphasize that the diagnosis of osteoporosis made by a doctor may come as a shock to the patient, especially that it is an incurable condition [5]. Additionally, the silent, initially asymptomatic, slow course of the disease, with the risk of unexpected bone fractures (including of the femoral head), may affect the mental state of the patient [3]. Also, negative emotions are intensified by chronic stress and living with the awareness of possible deterioration of conditions of functioning/physical activity during the day. This is confirmed by the results of our work, which proves that the duration of postmenopausal osteoporosis has a statistically significant impact on life satisfaction. Along with the duration of the disease, the respondents observed more negative emotions and deterioration of their quality of life.

In the study group, we observed moderate satisfaction with life among the subjects. This is a better result as compared to 268 examined women with osteoporosis, aged 45–55 years, in the city of Lublin. They had low satisfaction and were discontented with their lives [12]. Juczyński, the author of the Polish adapted version of the SWLS scale, while examining healthy women, also observed moderate satisfaction with life in the studied group [6]. A mean SWLS value similar to ours was published by Buliński et al. in a study involving 312 people representing a healthy Polish population aged over 60 years [13]. Also in the recently published study by Van Damme-Ostapowicz et al. involving elderly people in Bialystok, the level of life satisfaction among women was moderate [11].

There are no works on a group of people with osteoporosis with whom we could compare our research results. When entering the phrase “SWLS, osteoporosis” in the PubMed and Google Scholar search engines on 02/01/2022, we found three articles, one of which met our criteria [12]. It is interesting that the SWLS scale is used to assess life satisfaction in patients with other health conditions, including Crohn’s disease, ankylosing spondylitis, polycystic ovary syndrome, psoriasis and breast cancer [13–17]. The small number of articles in the group of women with postmenopausal osteoporosis assessed using the SWLS scale indicates the large scale of the problem and calls for further research in this field.

In the study group, the duration of osteoporosis had a statistically significant influence on life satisfaction. The diagnosis and the lack of sufficient knowledge about osteoporosis among women may reduce their life satisfaction at the initial stage of the disease. The respondents in our study had one of the worst values of life satisfaction in the first 5 years after the diagnosis; however, we also noted that regardless of the duration of osteoporosis, life satisfaction assessed on the sten scale was at the same level. Until now, publications have often emphasized low awareness of osteoporosis, bad health habits (e.g., smoking, drinking coffee, low calcium intake, lack of vitamin D3 supplementation) and lack of knowledge about preventive measures which help modify the patient’s lifestyle [18–21] such as avoiding excessive consumption of sugar, saturated fat, reducing salt intake and including more dairy products, fish, vegetables and fruits in the daily diet [22]. Słupski et al. also note the protective effect of osteoblastic compounds of plant origin [23].

Promoting health education, including nutrition, and an increased emphasis on physical activity in order to broaden the knowledge of risk factors for low bone mineral density in women, could improve the mental state of patients. Educated and health-conscious women may have fewer negative emotions. As shown by the respondents, education has a statistically significant impact on life satisfaction. Knowledge about the disease enables patients to apply preventive measures in everyday life.

We found that age has a statistically significant impact on life satisfaction and the quality of life in women. It should be emphasized that with age, bone homeostasis, maintained by a complex balance between bone formation and bone resorption, changes. Physiological bone remodeling and trabecular bone loss occur, which further increases the risk of fractures [24]. Our observations are consistent with the results obtained by Singh et al., who found that QoL deteriorates with age in women with osteoporosis [25]. A similar relationship was reported by Özsoy-Ünübol et al. [26]. Additionally, it should be stressed that as life expectancy increases, so does the number of comorbidities. Barcelos et al. emphasize that women with multiple diseases had a 38% higher risk of fracture as compared to those who suffered from one non-communicable chronic disease only or in whom no disease occurred [27]. Bone fractures and chronic diseases, including arterial hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus, limit the functioning of the patient, and consequently lower the quality of life. Therefore, there is an urgent need to increase health awareness in the population to enable patients to lead a healthy lifestyle and to promote active aging [27].

Our survey participants had a worse average quality of life as compared to the average QUALEFFO-41 results presented by Stanghelle et al. (26.7 ±13.1 points – in women in Norway) or Singh et al. (30.1 ±3.82 points – in women in India) [25, 28]. This indicates a lower QoL score for our population. On the other hand, our QUALEFFO-41 results were similar to those obtained in a study by Ciubean et al. including Romanian women (44.48–42.34 points) [29]. It may be related to the region of residence and access to medical care.

Our study also has some limitations. The main one was that it was conducted in one voivodeship city (Lodz) only, which may not reflect the results for the entire country. Another limitation was the fact that only two clinics were included in the analysis. It should also be emphasized that due to the small number of participants, we did not take into account the history of bone fractures, their number or the location of vertebral fractures, as most QoL studies on osteoporosis do. It would also be advisable to conduct a reanalysis in 2 or 4 years and to extend the above group. The study also has other limitations, as we did not analyze life satisfaction and the quality of life status depending on the last densitometric result and the type of treatment (tablets, injections). We admit that there is also a lack of information on the impact of other chronic diseases that could affect the mental state of the respondents. The aforementioned disadvantages create an opportunity for future research.

In conclusion, this study proves that the age and duration of osteoporosis affect the quality and life satisfaction of women. Extended pro-health education on the course, diagnosis and prevention of osteoporosis could further improve the mental state of patients. These results emphasize the need to introduce psychological care and educational programs that focus on women aged over 50 years.