Introduction

After the first confirmed case in Brazil on February 26, 2020, within a few weeks the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was also reported in all territories of Latin America [1]. This pandemic has been challenging for the already overburdened public healthcare systems of the region [2–5]. Latin America suffers from severe inequalities, and public healthcare systems are the only source of medical care for a large sector of the population who work in the informal economy [6]. Hence, in the months to come it will be seen whether Latin America can cope with the sanitary and economic challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Patients with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection may develop COVID-19, which has caused more than 1 million deaths worldwide to date [7]. Risk factors associated with death may vary between countries with different ethnical backgrounds [8–15]. These risk factors have been poorly described in Latin America, which represents a barrier to establishing proper epidemiological and clinical decisions to reduce the toll caused by this worrisome pandemic. Moreover, the lack of knowledge on clinical and epidemiological characteristics of the COVID-19 burden in neighbouring nations can introduce a factor of vulnerability for subsequent local epidemic waves, which usually obey mainly regional factors. Hence, it is critical to understand the factors associated with the outcome of COVID-19 in order to implement preventive and opportune treatment strategies to reduce the very high burden of this disease. Mexico is among the top five countries with the highest COVID-19 death tolls in the world [7].

Therefore, we aimed to describe the factors associated with death in persons with confirmed COVID-19 in Mexico.

Material and methods

We analysed the May 18, 2020, Ministry of Health’s official daily database on all people tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection by real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (rtRT-PCR) of nasopharyngeal fluids, for the clinical suspicion of COVID-19, in Mexico [16]. All patients who arrive at Mexican institutions dedicated to COVID-19 care are included in this official database, which is updated on a daily basis. This primary database contains information of basic demographics and traditional risk factors, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), immunosuppression, and other factors. A secondary electronic database was constructed for the present analysis, selecting case records with confirmed SARS-CoV-2. We excluded records with rtRT-PCR results pending, as well as those with negative results. A consent disclaimer was obtained for the aim of this analysis. This database was analysed without personal identifications, hospital record numbers, social security numbers, or contact details. All patients included in this database signed an informed consent for hospitalisation and for SARS-CoV-2 testing at the institution of origin.

Statistical analysis

Relative frequencies are expressed as percentages. Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as means with standard deviations (SD). Non-parametric continuous variables are expressed as medians with interquartile range (IQR). Pearson’s χ2 was used to assess proportions in nominal variables for bivariate analyses. Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U-test were performed to compare quantitative variables between two groups, in normal and non-normally distributed variables, respectively. Bivariable analyses were performed to select variables potentially associated with death to integrate a Cox-proportional hazards model adjusted for relevant epidemiological and clinical characteristics. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are provided. Actuarial analyses with the Kaplan-Meier method were also performed to assess the time to death after the initiation of COVID-19 symptoms. A p ≤ 0.05 was considered as significant, and all p-values were two-tailed.

Results

As of May 18, 2020, a total of 177,133 persons (90,586 men and 86,551 women) in Mexico received rtRT-PCR testing of nasopharyngeal fluids for the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 genome (Table I). There were 51,633 cases with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table II), and 125,500 cases with rtRT-PCR results pending (26,933) or negative results (98,567) (Table III).

Table I

Demographic characteristics and risk factors of the whole population tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection in Mexico, by sex (as of May 18, 2020)

Table II

Demographic characteristics and risk factors of the population with positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 infection in Mexico, by sex (as of May 18, 2020)

Table III

Characteristics of the population with pending or negative test results for SARS-CoV-2 infection in Mexico, by sex (as of May 18, 2020)

There were 7997 deaths among the whole cohort (case fatality rate, CFR = 4.52%, 95% CI: 4.42–4.61%): 5332 deaths among COVID-9-confirmed cases (CFR = 10.33%, 95% CI: 10.07–10.59%), 2009 deaths among persons with negative tests results (CFR = 2.04%, 95% CI: 1.95–2.13%), and 656 deaths in persons with pending results (case fatality rate: 2.44%, 95% CI: 2.26–2.63%) (test for homogeneity: p < 0.001). The median time (interquartile range, IQR) from COVID-19 symptoms onset to death was 9 days (5–13 days), and from hospital admission to death was 4 days (2–8 days).

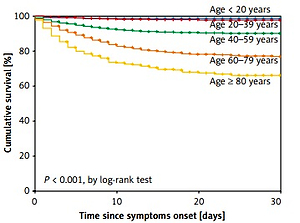

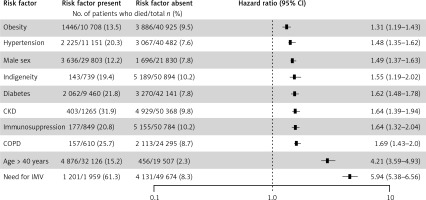

The analysis by age groups revealed that a markedly significant risk of death begins at the age of 40 years (Figure 1). Age, sex, and traditional risk factors (i.e. obesity, hypertension, diabetes, CKD, smoking, COPD, and cardiovascular disease among other factors) were associated with death in bivariate analyses (Table IV). To test the statistical independency of the association of covariables with CFR, we proceeded with an adjusted multivariate analysis. Thus, in a Cox proportional-hazards model controlled for relevant epidemiological and clinical antecedents, the risk factors associated with death were obesity, hypertension, male sex, self-reported indigenous ethnicity, diabetes, CKD, immunosuppression, COPD, age > 40 years, and the need for IVM (Figure 2). Only 1959 (3.8%) cases received invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), among whom 1893 were admitted to the intensive care unit (96.6% among those who received IMV).

Table IV

Bivariate analyses on risk factors associated with death in patients with COVID-19 in Mexico, by sex (as of May 18, 2020)

Discussion

This study shows that in Mexico, highly prevalent chronic diseases [17–20] are associated with COVID-19 death among persons with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. It was notable that indigenous ethnicity, an already recognised factor of vulnerability since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic [21–24], is a significant risk factor for death in the Mexican population. This factor may be related with limited access to a specialised health care within the indigenous communities, to different attitudes towards this specific pandemic, or to lack of knowledge on the COVID-19 spread and epidemiological behaviour in small communities of Mexico. Hence, this critical finding needs more analysis in future studies. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first reports about Amerindian ethnicity as a risk factor for death in patients with COVID-19 in Latin America [3, 25].

Although widespread, the COVID-19 pandemic has burdened some populations more than others, and there are growing concerns that minority groups could be disproportionately affected [26–28]. In this line of evidence, in the United States early data from New York City suggested that death rates from COVID-19 among African American people (92.3 deaths per 100,000 population) and Hispanic people (74.3 deaths per 100,000 population) were substantially higher than in Caucasian (45.2 deaths per 100,000 population) or Asian patients (34.5 deaths per 100,000 population) [27]. Moreover, the UK’s Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) reported that COVID-19 patients from ethnic minorities are younger than the white British patients, but patients from ethnic minorities have higher death rates [28]. After adjusting for age, sex, and geography, the authors of the IFS study found that CFR of patients from African ancestry is 3.5 times higher than that of white British people, while in those patients of black Caribbean and Pakistani ancestry, death rates were 1.7 and 2.7 times higher, respectively [28].

As we have shown in this study, other publications have reported that chronic diseases such as diabetes, asthma, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, air pollution, and obesity are associated with a high risk of infection and death in COVID-19 patients [10–15, 29–31]. These conditions occur and tend to converge more frequently in older people, but in the middle-aged population (aged 40–55 years) many other possible explanations emerge as to why they are also at high risk of death, when compared with younger persons aged < 40 years, even when they may be free of prevailing chronic diseases. Background genetic susceptibility and a differential gene expression influenced by different respiratory conditions may play a role [32, 33], but social factors that may increase exposition to infection can also be considered, such as the middle-aged people living in densely-populated areas where economic activities abound, more frequent usage of public transportation, and employment in informal or low-paid jobs without sick pay insurance, among other factors [34].

The healthcare system in Mexico was already fragile when the first reported death from COVID-19 occurred on March 18, 2020, the day when the first 118 cases had been confirmed [16]. Moreover, health care fragmentation and segmentation are important problems for the complex and vulnerable sanitary system in Mexico [35]. This factor may also impose a challenge to the COVID-19 frontline, because Mexico has high rates of hypertension, obesity, and diabetes, all of which are risk factors for severe disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection in Mexicans [11, 12, 36]. The prevalence of this comorbid risk factors rises in adults with vulnerable social conditions, who have limited access to quality health care, and are characterised by high poverty levels [35]. Identification of risk factors for relevant clinical outcomes is of utmost importance to design specific therapies and to select effectively the most vulnerable populations to administer preventive measures, vaccination, and better health care [37–41].

The present study has limitations that need discussion for the correct interpretation of the present findings. Firstly, this database contains self-reported information on risk factors, comorbidities, and demographic characteristics, without laboratory or imaging information to confirm or even identify new putative mortality risk factors. Although this database is updated on a daily basis by comprehensive collaboration of all sanitary institutions, it depends essentially on passive testing performed in hospitals when people seek medical care, and as a consequence, this database cannot be considered as truly representative of the whole Mexican population. Moreover, although in Mexico self-reported indigenous ancestry is considered as reliable [42], no genetic ancestry informative markers were obtained to confirm that ethnicity – and not only social disparities – is linked with the risk of death, which is a major finding of our study. A new analysis is currently under preparation to test, from the medical and epidemiological perspective, whether ethnicity is associated with major COVID-19 risks through social inequalities and limited quality health care.

In conclusion, highly prevalent chronic comorbidities are risk factors for COVID-19 death in Mexico. Indigenous ethnicity is a significant death risk factor in Mexicans, and therefore, this critical finding requires analysis in future studies.