Introduction

In clinical applications, blood transfusion is a common medical intervention. Over fourteen million blood units are transfused every year in the United States [1]. Non-infectious hazards such as transient ischemic incidents, unstable angina, hemolytic transfusion reactions, circulatory overload, and acute lung injury are the leading complications of blood transfusion in developing countries [2–4]. Individuals with preexisting disorders, such as atherosclerosis or diabetes transfused with red blood cells stored for over fourteen days, are susceptible to high mortality rates [5–7]. Moreover, autologous transfusion of old red blood cells (RBC) has been shown to promote M2 macrophage polarization and increase the expression of their surface CD68 and CD200R proteins and oxidative stress [8]. In contrast, other studies have not found any adverse effects in patients transfused with red blood cells stored for longer times [9, 10].

The US Food and Drug Administration has authorized the storage of red blood cells for up to forty-two days [1]. Nevertheless, it is known that storing red blood cells promotes progressive structural and functional alterations that inhibit their viability and oxygen-carrying capacity, resulting in hemolysis and the release of various particles such as hemoglobin and iron in the circulatory system [11–13]. Also, free circulating heme mediates macrophage polarization and attenuates the M1 and M2 markers’ expression [14]. Additionally, it was found that autologous blood transfusion, among other fluid resuscitations, causes certain types of stress on hepatic mitochondria and apoptosis, suggesting a close relation between autologous blood transfusion and adverse effects in some patients [15]. Therefore, further investigations are required to elucidate the underlying mechanism of the different storage times on red blood cell transfusion.

Hematopoiesis is a complex biological process involving intricate signaling pathways, among which is insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2); it is known to be potently expressed during the expansion of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) [16], modulates murine hematopoietic stem cell maintenance [17], and has a role in endothelial progenitor cell homing [18]. IGF2 is involved in red blood cell oxidative stress, oxygen delivery, and the aging of red blood cells [19]; it is also involved in the regulation of macrophage metabolism and polarization [20, 21]. Based on the mentioned findings, the present study aims to elucidate the effect of fresh autologous blood transfusion on red blood cell damage concerning the IGF2 axis in diabetic mice.

Material and methods

In vivo analysis and animal modeling

In the current in vivo study, Swiss male mice 6–8 weeks old were purchased from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and maintained in a clean environment with constant temperature and humidity. Mice were grouped correspondingly (20 mice/group); the normal group was on a regular diet, and the T2D modeling groups were fed a high-fat and high-sugar diet for 3–4 months and then injected with streptozotocin (STZ) (Sigma Aldrich, USA) at 60 mg/kg for 7–10 days until T2D was achieved. The successful modeling of T2D was determined by measuring the animals’ fasting blood glucose and fasting insulin content. All procedures were performed in accordance with ethical guidelines for animal experimentation to ensure minimal animal suffering. Diabetic animals were divided into two groups, T2D (diabetic mice with no further treatment), and fABT + T2D (diabetic mice subjected to fresh autologous blood transfusion).

All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the animal ethical organization and obtained the permission of the Shanghai Gongli Hospital, Naval Military Medical University

Preparation of fresh autologous blood transfusion fluid

Fresh autologous blood was obtained from healthy Swiss mice and was subjected to certain preservatives such as mannitol to improve RBCs’ membrane stability, reduce sugar accumulation, and improve their oxygen-carrying capacity. Blood samples were transfused forthwith.

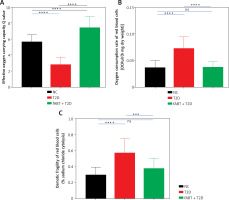

Analysis of physiological erythrocyte index

After treating the animals accordingly, animals were sacrificed, and the blood samples were collected from the abdominal aorta and stored at 4°C in tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and defoaming agent (10 µl) until further analysis. Simultaneously, we stimulated the arterial oxygen partial pressure as previously described [22]. Briefly, the test parameters were as follows: O2 = 16 ml/min, CO2 = 3 ml/min, N2 = 120 ml/min, flow rate: 100 ml/min, 37°C to sample inflatable 9 min. One milliliter was used for blood gas analysis as previously described [23]. The determination of the erythrocytes’ oxygen-carrying capacity was done using the Q value following this formula: Q = 20 × (S1 – S2) ml; S1 is the oxygen saturation of Hb after the oxygen partial pressure reached 100 mm Hg and stabilized, while S2 is the oxygen saturation of Hb after the oxygen partial pressure of mixed gas was 40 mm Hg. The erythrocytes’ oxygen consumption rate was determined as previously described [24].

For osmotic fragility testing, the saline dilution technique was performed as previously described [25]. Briefly, a phosphate buffer stock solution containing 10% NaCl was prepared and then diluted using distilled water until it reached 1% NaCl solution. Each treatment group included sixteen serial dilutions containing 0.85 to 0.0% NaCl. Blood samples (20 µl) were added to each tube, mixed by inversion, and then left to settle at room temperature for 30 min. Next, all samples were centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 min. Then, the supernatant’s optical density was determined at 540 nm using a spectrophotometer. At 0% NaCl we assumed 100% hemolysis. The percentage of erythrocytes exposed to each saline concentration was determined from the supernatant at 540 nm compared to the 0.0% NaCl supernatant for each series of dilutions.

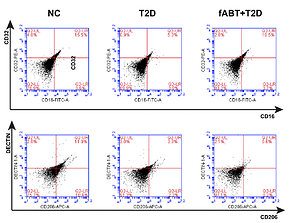

Flow cytometry

Blood samples were diluted at a 1 : 3 ratio using PBS solution containing heparin. Then, 3 ml of Ficoll-Hypaque solution (Beyotime Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was added slowly to each tube, followed by centrifugation twice at 2500 g for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatants were transferred to new tubes containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Initially, we analyzed the percentage of macrophages after staining the monocytes with allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated monoclonal antibody against mouse CD32 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA); subsequently, the phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibody against mouse CD206 (eBioscience, USA) was separately stained with the monocytes for 1 h at 4°C. Subsequently, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with the secondary antibody – anti-mouse (IgG). Finally, the monocytes were fixed with paraformaldehyde for 30 min and analyzed using FACSCalibur (eBioscience).

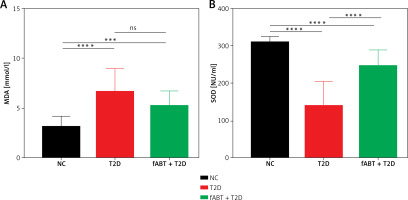

Oxidative stress and mitochondrial function analysis

Mitochondrial protein concentration was assessed as previously described [26]. The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in erythrocytes was determined as previously described [27]; the activity of SOD is expressed in nitrite units (NU) per ml (NU/ml). Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in erythrocytes were determined as previously described [28]. The assay was performed using a reaction with thiobarbituric acid and analyzed using a spectrophotometer. The results are expressed in µmol/l.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA from blood samples was extracted using Trizol reagent (Takara, Japan). Following the manufacturer’s protocol, the corresponding complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Promega, Kansas, USA). The RT-qPCR experiment was performed using SYBR Green Master mix (Applied Biosystems, USA) and StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA).

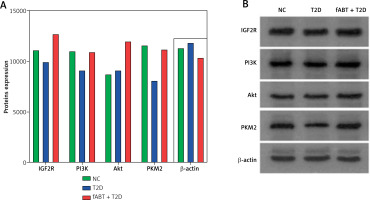

Western blotting

Proteins from blood samples were extracted using RIPA buffer (Beyotime, China), and their concentration was determined as indicated in the BCA Kit (Thermo, USA). Each protein sample was added to the sample buffer and boiled for 10 min at 95°C. 30 µg of each sample was loaded and electrophoresed using 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. Next, membranes were blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature and subsequently incubated with each corresponding primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The antibodies were as follows: IGF2R (1 : 1000, Santacruz, USA); PI3K (1 : 1000, Cell Signaling, USA); Akt (1 : 1000, Cell Signaling, USA); PKM2 (1 : 1000, Cell Signaling, USA); β-actin (Beyotime, China). The next day, membranes were rinsed with TBST three times, then incubated with the secondary antibody and incubated at room temperature for 1 h, followed by washing three more times. A chemiluminescence reagent was used for the visualization of protein bands. All target protein bands were analyzed using Image J software (ImageJ NIH, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were conducted using Graph-Pad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA). Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed using an unpaired t-test. Multiple group analysis was conducted using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was considered when p < 0.05.

Results

Fresh autologous blood transfusion (fABT) reduced M2 macrophage polarization and enhanced hepatic mitochondrial metabolism

Although some studies have reported no significant adverse effects of transfusing red blood cells in patients undergoing treatment or operations, recent studies have indicated the adverse impact of old red blood cell transfusions [8, 29]. We tested the effect of fABT in diabetic mice and found that it reduced M2 macrophage polarization over M1 compared to the negative control and diabetes groups (Figure 1 A). Noting that different fluid resuscitation impacts hepatic mitochondria [15], we found that fABT significantly improved hepatic mitochondria in diabetic mice compared to the negative control and diabetes groups (Figure 1 B).

fABT alleviates oxidative stress in diabetic mice

It is known that storing red blood cells alters their oxidative processes [29, 30]. Such processes have unique markers to determine their oxidative stress status, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and malondialdehyde (MDA) [31]. The results showed that fABT decreased MDA levels (Figure 2 A) and improved the level of SOD (Figure 2 B) compared to the T2D and NC groups. These results suggest that fABT is advantageous for sustaining protection against red blood cell oxidative stress.

fABT modulates the IGF2R/PI3K signaling pathway in diabetic mice

Based on the results mentioned above, we further investigated the underlying mechanism by which fABT affects biological processes in diabetic mice. Our results showed that fABT promoted the IGF2R/PI3K signaling pathway, evidenced by the increased expression of IGF2R, PI3K, AKT, and PKM2 proteins compared to the T2D group (Figure 3). These data indicated that fABT potentially exerts its effect in diabetic mice through the IGF2R/PI3K signaling pathway.

fABT promoted erythrocyte functions

The abovementioned results confirmed the vital role of fABT in the biological functions in diabetic mice; therefore, we determined the erythrocyte functions in diabetic mice after receiving fABT. Our data showed that fABT enhanced the oxygen-carrying capacity of erythrocytes (Figure 4 A) and reduced oxygen consumption (Figure 4 B) and osmotic fragility (Figure 4 C) compared to the T2D group. These results confirmed the vital effects of fABT on erythrocyte functions and various biological processes, such as in diabetic mice.

Discussion

The underlying mechanism concerning the adverse outcomes of red blood cell transfusion remains elusive. Several studies have attempted to extrapolate the mechanism by which transfusing stored red blood cells could adversely affect patients [8, 29]. However, more investigations are required to establish a solid background regarding the utilization of stored/fresh autologous blood transfusion. Previous studies have found that the transfusion of old red blood cells in animals promotes M2 macrophage polarization and exacerbates the expression of inflammatory factors IL-10 and CCL22 [8]. Surprisingly, the transfusion of 14 days-stored red blood cells promoted the expression of pro-inflammatory factors iNOS, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18, whereas their levels decreased when 35 days-stored red blood cells were transfused [8]. However, the same settings in humans showed a slight increase in the non-transferrin-bound iron (NTBI) with no increase in other pro-inflammatory cytokines [32]; on the other hand, an animal model of blood transfusion exhibited a pro-inflammatory cytokine storm and increased NTBI levels [33]. These phenomena were suggested to be caused by the regulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory responses. Hence, debatable opinions arose regarding the differences in the outcomes of different storage times of red blood cells, which in some cases was accounted for by the limitation of study samples.

In diabetic patients, the use of autologous blood transfusion (hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells) has shown progressive outcomes, especially in diabetes type 1 [34]. This process exhibited potentially safe and favorable outcomes in diabetes type 1 patients [35]. To our knowledge, no investigations have been conducted on autologous blood transfusion in animals or humans with diabetes type 2. Research works have established that monocytes get recruited to peripheral tissues such as the liver to become resident macrophages and contribute to local inflammatory responses, progression of insulin resistance, or even pancreatic dysfunction. Also, mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of diabetes type 2 [36], and it has been established that in type 2 diabetes, there is an imbalance in the ratio of M1/M2 macrophages and an elevation in their polarization [37].

Therefore, our study focused on the effects of fresh autologous blood transfusion (fABT) in type 2 diabetic mice. The results showed that fABT reduced the M2 macrophage polarization and improved hepatic mitochondrial metabolism/function. It has been reported that transfusion of stored red blood cells promotes erythro-phagocytosis and hemolysis [38–40], leading to inflammatory and oxidative stresses [41, 42]. Oxidative stress analysis revealed that fABT reduced oxidative stress in T2D mice, as evidenced by elevating SOD levels.

Further analysis is required to uncover the possible underlying mechanism by which fABT exhibits favorable outcomes in T2D mice. Duly, IGF2R is vital in hematopoiesis and regulating oxidative stress, erythrocyte functionalities, and macrophage polarization [16–21]. Our data indicate that fABT modulates the IGF2R/PI3K signaling pathway and exhibits favorable outcomes evinced by improved oxygen-carrying capacity of erythrocytes and reduced osmotic fragility and oxygen consumption.

In conclusion, our study was the first to elucidate the beneficial effect of fABT in a T2D animal model and elucidate the potential mechanisms by which fABT acts. These data provide a solid ground for understanding the benefit of utilizing fresh red blood cells. Further investigations are required to overcome the present study’s limitations, such as including T1D and different storage times of RBCs, and also integrating human blood samples into our animal models to produce results that could cover the majority of previous debatable results.