Introduction

Lung cancer has remained the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide for over 50 years [1, 2]. There has been a slow but steady decline in its incidence among men and an increase among women within the last decades [3], the smoking habits evolution [2], however there were 1.14 billion smokers worldwide in 2019, with smoking contributing significantly to mortality [4]. Despite enormous advances in technology and medicine, in most countries, treatment outcomes have remained virtually unchanged since the 1980s [1, 2].

In Europe, only 10–16.5% of lung cancer patients are cured, and 80-85% die within 5 years from the initial diagnosis, half of them within 2 years [5–7]. Among the EU member states, Poland ranks among the highest in mortality from lung cancer [7]. The latest data from the GLOBOCAN 2022 study indicate that Poland is second only to Hungary, which has the highest age-standardized mortality rate (ASR 143.7/100,000), while Poland has an ASR of 133.1/100,000 [7]. The high mortality rate in Poland contrasts with lower rates in Western and Northern European countries such as Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Iceland (ASR below 80/100,000) [7].

Lung cancer is the most common malignancy in Poland, accounting in 2019 for 27,600 new cases of lung cancer (16.1% of all cancers in men and 9.9% in women), and 27,500 deaths (27.4% of all cancer deaths in men and 17.9% in women) [8]. In 2022, these rates did not significantly change to 25.8% of all cancer cases and 27% of all cancer deaths [8]. Incidence and mortality rates vary across Poland, with higher values observed in northwestern regions [8]. At the same time, lung cancer accounts for almost one in three cancer deaths in the Greater Poland region [9].

Between 2000 and 2016, the standardized mortality rate from lung cancer in men fell from 148.8 to 114.5 per 100,000 (an average annual decrease of 1.7%), while in women it increased from 25.7 to 37.6 per 100,000 (an average annual increase of 2.3%) [10]. From 2017 to 2022, the number of lung cancer cases in men in Poland decreased from over 22,000 to 20,700 [11]. This decline is attributed to a steady decline of lung cancer incidence among men since 1995 [8].

In 2014, as many as 93% of lung cancer deaths in men and 76% in women could be directly attributed to tobacco smoking [12]. Although in Poland, daily smoking has been declining since the 1970s, the challenges remain [13]. In a nationwide study conducted in 2024 by Jankowski et al., as many as 30.4% of adult Poles reported smoking cigarettes in the last 30 days, including 24.5% who were daily smokers [14]. In 2022, 28.8% of adult Poles (30.8% of men and 27.1% of women) reported daily smoking [9, 11]. Gender differences have been narrowing, with an increasing number of women smoking [15]. People with lower education and poorer economic status tend to smoke more frequently, and those living in rural areas find it more difficult to quit and are more likely to relapse [14].

Lung cancer is the third most expensive malignancy in terms of sickness absence in Poland, after breast and prostate cancer, with associated costs amounting to approximately PLN 125 million in 2020 [16]. However, these costs represent only a small part of the total indirect costs associated with lung cancer, estimated at PLN 3.3 billion in 2017 [12, 16]. These indirect costs include premature deaths, permanent disability, presenteeism among patients and caregivers, and caregiver absenteeism [12, 16].

Smoking cessation and social education (particularly in the adolescent and young adult group) are paramount elements of primary lung cancer prevention and those who have already been diagnosed with lung cancer; smoking cessation can still lower the incidence of early death [13]. However, this should be boosted by effective secondary prevention, i.e., lung cancer screening (LCS). Two randomized clinical trials showed more than a 20% mortality reduction in the at-risk populations by virtue of LDCT LCS [14, 15, 17]. In the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) conducted in the United States, 53,454 participants aged 55 to 74 years, who were current or former heavy smokers with a smoking history of at least 30 pack-years, were randomly assigned to low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) and chest radiography groups and underwent three annual screening examinations. There was a 20% reduction in lung cancer-specific mortality in the LDCT group compared to the chest radiography group [15, 17]. The Dutch-Belgian Randomized Lung Cancer Screening Trial (NELSON), in which 16,000 individuals were randomly assigned to LDCT or observation groups, showed a 26% mortality reduction in the LDCT group [14].

As a result, a population-based LDCT LCS was implemented and reimbursed by local health authorities in 2016 in the United States, and between 2019 and 2020 in Taiwan, Korea, and Croatia. In December 2022, the European Commission recommended introducing LCS (with a stepwise approach) for current and former smokers who have quit smoking within the previous 15 years, are aged 50 to 75 years, and have a smoking history of 30 pack-years. Poland and Great Britain were the first European countries to start nationwide pilot studies in 2020. According to the declaration of the Ministry of Health, the launch of the Polish nationwide LCS program is planned for 2025. Another two countries, Australia and the United Kingdom, have also announced LCS launching in 2025.

Primary prevention, using effective smoking cessation intervention with behavioral and pharmacological support for current smokers, is a mandatory element of LCS. Such intervention leads to a reduction of active smoking among screening participants and enhances the cost-effectiveness of LCS. Patients with lung cancer often show increased motivation to quit smoking due to the direct impact on their health status [18, 19]. However, Poland has not yet established an effective set of procedures to proactively support people who are willing to quit smoking regardless of the screening result [16, 20].

Despite international recommendations (USPSTF, NICE, WHO), Poland lacks protocols for screening using LDCT and consistent data on the effectiveness of smoking cessation programs accompanying screening. This variability hinders the systematic implementation of LCS and points to the need for a national expert consensus that considers the local epidemiological, organizational, and clinical context. The LCS represents a critical moment for smoking cessation, as participation in screening provides an opportunity to engage high-risk individuals when motivation to quit may be heightened. Recognizing this framework supports the rationale for integrating structured cessation interventions into LDCT programs.

The primary aim of this study is to synthesize existing data and establish a national expert consensus, with the goal of formulating practical recommendations for implementing LCS LDCT programs in the Polish healthcare system, while leveraging the LCS context as a teachable moment to enhance smoking cessation outcomes. This consensus statement provides recommendations to support individuals in Poland, particularly those identified through lung cancer screening programs, in quitting smoking and improving their prognosis. A panel of multidisciplinary experts conducted a thorough review of the existing literature on smoking cessation and cancer outcomes to inform these guidelines.

Methods

In July 2023, a hybrid expert consensus meeting was held at the Medical University of Gdansk. Polish national experts on tobacco control, including representatives of public institutions, academia, and specialists in LDCT and cancer screening studies, were invited to discuss the issue of smoking cessation intervention within LCS. The expert team consisted of seven specialists with diverse medical and public health backgrounds. It included clinicians such as a thoracic surgeon, oncologists specializing in lung cancer and molecular research, a radiologist, public health and epidemiology specialists, with experts in population health, cancer registries, and tobacco control.

The open discussion was structured according to the stated objectives; the team was divided into subgroups, each focusing on a specific area: (1) a randomized controlled trial on smoking cessation, (2) a selection of Polish recommendations for smoking cessation in primary and secondary prevention, and prevention from passive smoking from the last 5 years, and (3) meta-analyses of strategies for delivering smoking cessation interventions during targeted lung health screening. Each team conducted its reviews independently.

The reviews were conducted systematically, following transparent search principles to ensure reproducibility and minimize bias. A comprehensive search was carried out in PubMed/Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, JBI Evidence Synthesis, and ClinicalTrials.gov for studies published in English or Polish up to the year 2023. Search terms combined keywords and MeSH terms related to lung cancer screening, low-dose CT, smoking cessation, tobacco use, and specific interventions, including pharmacotherapy, counseling, and behavioral support, using appropriate filters for human studies and adult populations. Studies were included if they reported a smoking cessation intervention among LDCT lung cancer screening participants who used any tobacco product and were excluded if they provided an insufficient description of the intervention or outcomes, were non-human, or did not focus on lung cancer screening populations. All records were independently screened, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion within the team. This approach, together with the broad database search and clearly defined criteria, ensured a consistent and transparent selection process.

The findings of the three subgroups were subsequently discussed collectively in a meeting, and consensus was reached through iterative rounds of discussion. This structured approach allowed the panel to combine international and national evidence, evaluate its applicability to Poland, and develop evidence-informed, context-specific recommendations for smoking cessation in the setting of lung cancer LDCT screening. After the meeting, the draft consensus statement was circulated to the panelists for discussion and editing. The present document was formulated and approved by all participating experts. To summarize the work, a follow-up meeting was held in August 2024.

Review of existing literature

Randomized controlled trials on smoking cessation

In the ClinicalTrials.gov database, a search for the “smoking cessation” intervention/treatment yields 2053 studies, of which 451 have published results [18] (accessed on 1.08.2023). Of these, 196 were randomized controlled trials. Refining the search to the condition “lung cancer” yields eight studies with results. Following the consensus goal, these studies were thoroughly analyzed by the expert panel and were included in the subsequent sections.

The Dutch-Belgian screening study (NELSON) [19] and the Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial (DLCST) [20] have published analyses of the effect of screening on smoking habits. In the male cohort of the NELSON study, smoking cessation rates in the CT and control groups after approximately 2 years were 13% and 15%, respectively [21]. The DLCST included all participants during five screening rounds [20, 22]. Subjects in both randomized groups (screened and unscreened) were given brief smoking cessation counseling by trained nurses. The smoking cessation rates after 1 year of screening in the screened and control groups were 11% and 10%, respectively. Due to smoking relapse, the net quit rate was 6% [20]. LCS itself has no direct effect on the smoking status of the participants [22]. However, LCS may serve as a “teachable moment’”, in which motivation to stop smoking is enhanced. Indeed, participants of LCS trials, regardless of whether being or not subjected to CT scanning, show an overall quit rate of approximately 10–13% over 4–5 years, i.e., higher than the general population [20, 22].

A recent randomized clinical trial by Cinciripini et al. [23] compared three intervention models: a standard quitline (QL), an enhanced quitline with clinician-managed pharmacotherapy (QL+), and integrated care (IC) combining pharmacotherapy and intensive counseling within the LCS setting. The study included 630 smokers eligible for LCS and demonstrated that the IC model was the most effective, achieving the highest abstinence rates: 37.1% at 3 months and 32.4% at 6 months, compared to 25.2% and 20.5% for QL, and 27.1% and 27.6% for QL+, respectively. The authors emphasized that intensive counseling and personalized pharmacotherapy in the IC model significantly contributed to its superior outcomes. Bayesian analysis further confirmed the IC model’s advantage, with high probabilities of positive absolute risk differences compared to QL and QL+ [23].

In contrast to the impact of LCS, smoking cessation interventions such as telephone-based counseling have been shown to be effective. A pilot study in which current smokers undergoing LCS were offered telephone-based counseling showed a quit rate of 17.4% in the intervention group compared with 4.3% in the group without counseling [24].

However, some studies have not shown significantly increased quit rates associated with smoking cessation programs within the LCS setting. The effectiveness of smoking cessation counseling for smokers participating in the Alberta Lung Cancer Screening Study was studied in a randomized (1 : 1) controlled trial comparing an intensive telephone-based smoking cessation counseling intervention with usual care (information pamphlet) [25]. The primary endpoint, self-reported thirty-day smoking abstinence at 12 months post-randomization, was achieved in 12.6% and 14.0% of participants in the control and interventional arms, respectively. In conclusion, an intensive telephone-based smoking cessation counseling intervention, which incorporated LCS results, did not show significant increases in quit rates at 12 months or beyond [26].

On the other hand, smoking cessation interventions have proven effective for people at high risk of lung cancer who attend LDCT screening. In the Optimizing Lung Screening Trial (OaSiS), which included 26 radiology facilities across 20 states, participants demonstrated a significant reduction in tobacco use over time, without difference between the trial arms [27]. In a study by Murray et al., patients with lung cancer who attended LCS and then participated in a personalized smoking cessation study achieved smoking abstinence rates exceeding 30% [28]. A randomized trial of telephone-based smoking cessation treatment within LCS showed that delivering 8-week telephone counseling and a nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) intervention along with LCS effectively increased short-term smoking cessation and was cost-effective [29]. Even with modest quit rates, integrating cessation treatment into LCS programs may significantly impact tobacco-related mortality at reasonable costs.

This observation is further supported by another study, where out of 3,063 screen-eligible individuals who were smoking at a baseline LCS examination, 2,736 (89.3%) attended in-hospital smoking cessation counseling [30]. The 1-year quit rate was 15.5%. Additional improvements were observed in smoking severity scores (the Heaviness of Smoking Index), including the number of cigarettes smoked daily, the time to first cigarette, and the number of quit attempts. However, among those who reported quitting within the previous 6 months, 6.3% had resumed smoking at 1 year. Notably, 92.7% of respondents reported satisfaction with the hospital-based smoking cessation program.

There is a variability of pharmaceutical support strategies used for smoking cessation. A study comparing cytisine with varenicline showed a non-inferiority of the former in the smoking cessation effectiveness [31]. A randomized non-inferiority trial involving 377 participants revealed that a standard 4-week cytisine treatment was less effective than the standard 12-week varenicline treatment for smoking cessation [32]. However, adherence to the treatment plan was higher, and adverse event rates were lower among participants assigned to cytisine treatment. In turn, a randomized New Zealand trial found that cytisine was at least as effective as varenicline in supporting smoking abstinence, with significantly fewer adverse events [33]. Likewise, the results of the Screening and multiple intervention on lung epidemics randomized trial suggest that cytisine is a valuable and inexpensive option for smoking cessation within LCS, with potential benefits for all-cause mortality [34].

Systematic reviews with meta-analysis from the last 5 years on smoking cessation interventions within lung cancer screening

Two systematic reviews, each incorporating meta-analyses relevant to the topic, were identified. Both reviews focused on smoking cessation interventions, particularly in the context of LCS, and were published within the last 5 years.

The Williams et al.’s systematic review and meta-analysis involving 5,076 participants across 13 studies, highlighted the positive impact of intensive interventions, comprising three or more counseling sessions combined with pharmacotherapy, on quit rates and quit attempts [35]. In contrast, non-intensive interventions, with fewer counseling sessions, showed minimal improvement in quit rates. The study emphasized the importance of integrating robust smoking cessation support within LCS programs to improve cessation outcomes but also acknowledged the need for further research to address certain limitations and biases. Similarly, another extensive review of 85 trials involving nearly 94,000 participants found that pharmacotherapy and in-person counseling were the most effective smoking cessation strategies within LCS. While electronic/web-based interventions and telephone counseling also improved quit rates, they were less consistently effective [36]. The study highlighted the benefits of combining multiple intervention methods and recommended that implementation strategies should consider such factors as feasibility, scalability, and cost-effectiveness to maximize impact.

The European Respiratory Society recommendations further emphasized the importance of incorporating smoking cessation services into LCS programs [37]. Considering a significant proportion of current smokers among LDCT participants, this document recommended embedding comprehensive cessation services, including counseling, pharmacotherapy, and regular follow-up visits, directly within the screening process. This approach is seen as an effective way to improve public health outcomes by leveraging the screening setting to effectively combat tobacco use.

A selection of Polish recommendations for smoking cessation for primary prevention, secondary prevention, and prevention of passive smoking from the last 5 years

According to the 2022 guidelines for the treatment of nicotine dependence, healthcare providers need to document tobacco use in patients’ medical records and regularly update this information [38]. The guidelines recommend offering intensive quitline counseling to all participants and suggest group and telephone counseling as additional options. NRT is strongly endorsed for all smokers, except pregnant women and is particularly recommended with behavioral support. Bupropion and varenicline are recommended for most smokers, and cytisine is recommended for these smokers except for pregnant women and individuals with mental health conditions. A key recommendation is to combine pharmacological treatments with behavioral support to maximize effectiveness. The guidelines also emphasize the need for ongoing training for healthcare professionals and suggest making nicotine addiction treatment more affordable for patients.

In 2018, Rzyman et al. emphasized the need to integrate smoking cessation programs with LDCT LCS at each step of the program [39]. Such integration improves cost-effectiveness and increases quality-adjusted life years gained. However, sustaining cessation and preventing relapses remain challenging, particularly for socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. The proposed intervention includes systematic support based on smoking status, including diagnostic evaluations, psychological support, and pharmacological aid. Active smokers receive assessments of smoking intensity and dependence, while former smokers receive tailored motivational support. The study also highlights the importance of addressing passive smoke exposure and engaging participants’ social circles to create a smoke-free environment, aiming to boost cessation success and reduce relapses.

Smoking cessation intervention methods and their effectiveness

Various smoking cessation methods have shown varying levels of effectiveness, as summarized in Table I. Behavioral interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy [40] and motivational interviewing [41], significantly increase quit rates compared with no intervention or placebo, especially when combined with pharmacotherapy, e.g., varenicline or NRT [42]. NRT reduces withdrawal symptoms, while varenicline is more effective than other cessation interventions, particularly in smokers with depression [42, 43]. In addition, telephone counseling and mobile health support further enhance adherence and extend nicotine abstinence [44, 45].

Table I

Effectiveness of various smoking cessation methods, including behavioral interventions, motivational interviewing, and pharmacotherapy, based on their impact on sustained abstinence rates

| Method | Effectiveness |

|---|---|

| Educational materials | Motivational interviewing and health education are both efficacious via different pathways to smoking cessation [48]. |

| The use of the transtheoretical model in education allows the creation of various intervention materials adapted to the patient’s contemplation stage [49]. | |

| No intervention/placebo | The rate of sustained 12-month abstinence was 8.4% (31 participants) in the cytisine group as compared with 2.4% (nine participants) in the placebo group [50]. |

| Self-learning | Among people who stop smoking successfully with behavioral support and know the risky situations associated with relapse, the use of educational materials to cope with the urge to smoke, did not reduce relapse [51]. |

| Cognitive behavioral therapy | Both cognitive behavioral therapy and basic health education reduce nicotine dependence [40]. |

| Varenicline added to behavioral therapy increases its effectiveness [52]. | |

| Behavioral interventions | Behavioral interventions increase smoking cessation rates from a baseline of 5% to 11% in control groups to 7% to 13% in intervention groups. They include face-to-face counseling, telephone counseling, and self-help materials [53]. |

| Used alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy they are most effective in achieving smoking cessation [54]. | |

| Motivational interviewing | Results in higher quit rates than brief advice to stop smoking or usual care [41]. |

| Can help people who smoke quit, but should include many sessions and be specifically adapted and modified for the particular study population [41]. | |

| Provided online is more successful at assisting people who smoke in lowering their daily cigarette intake and supporting their mental health during the smoking cessation process [55]. | |

| Telephone and online support and quitlines | Increased effectiveness of psychopharmacological therapies and extended time of nicotine abstinence by mobile health solutions [56]. |

| Telephone counseling significantly increases the short- and long-term abstinence rates of the self-help intervention [44]. | |

| Text messaging, web-based services, and social media support | Can increase the likelihood of adults quitting compared with no intervention or self-help information, and can be a cost-effective adjunct to other treatments [45]. |

| Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) | Transdermal NRT, compared to placebo, significantly reduces withdrawal symptoms in the first few weeks after quitting smoking. It is an important addition to low-intervention therapy [43]. Combining long-acting forms of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) with short-acting forms significantly increases the likelihood of successful smoking cessation compared to the use of only one form [57]. |

| Varenicline | Phone counseling has a greater advantage for early cessation and may increase medication adherence when used in conjunction with varenicline [58]. |

| May be more effective than bupropion [59]. | |

| Can be used with a high success probability with tobacco cessation in young people with asthma, but the smoking relapse rate after the end of treatment is high [60]. | |

| Is safe and more effective in sustaining abstinence than nicotine replacement therapies, placebo, or bupropion [61]. | |

| For people who smoke and suffer from depression, varenicline plus counseling may be the best pharmacological smoking cessation treatment [42]. | |

| Cytisine | Is more effective than placebo and NRT and non-inferior to varenicline, with fewer adverse events [62]. The study found that 77% of patients were satisfied with cytisine treatment, with 76% remaining abstinent at the post-treatment visit. |

| Combined with counseling from community pharmacists does not significantly improve the continuous abstinence rate at week 48, though there were improvements at weeks 2, 4, and 12 [63]. The cytisine adverse events were common but non-serious. | |

| Exhibited greater reductions in the number of cigarettes smoked compared to placebo [64]. |

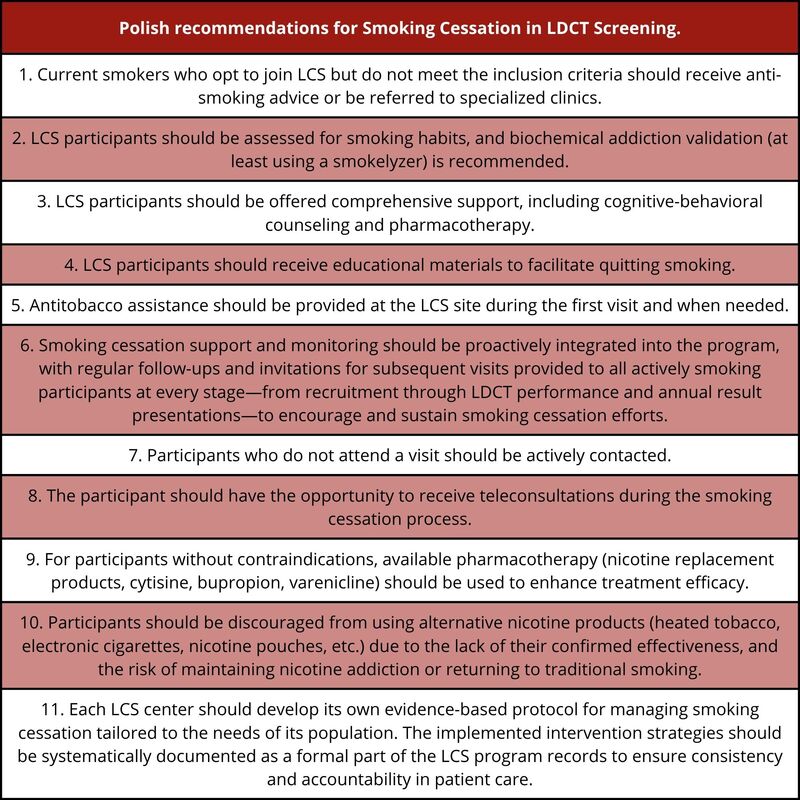

The literature reviewed and discussed in light of this expert consensus allowed us to formulate specific recommendations tailored to the Polish population. By integrating what is already known in the context of other Polish guidelines and recommendations [38, 39, 46], we have developed a set of recommendations outlined in Box 1.

Box 1

Polish recommendations

Current smokers who opt to join LCS but do not meet the inclusion criteria should receive anti-smoking advice or be referred to specialized clinics.

LCS participants should be assessed for smoking habits, and biochemical addiction validation (at least using a smokerlyzer) is recommended.

LCS participants should be offered comprehensive support, including cognitive-behavioral counseling and pharmacotherapy.

LCS participants should receive educational materials to facilitate quitting smoking.

Antitobacco assistance should be provided at the LCS site during the first visit and when needed.

Smoking cessation support and monitoring should be proactively integrated into the program, with regular follow-ups and invitations for subsequent visits provided to all actively smoking participants at every stage – from recruitment through LDCT performance and annual result presentations – to encourage and sustain smoking cessation efforts.

Participants who do not attend a visit should be actively contacted.

The participant should have the opportunity to receive teleconsultations during the smoking cessation process.

For participants without contraindications, available pharmacotherapy (nicotine replacement products, cytisine, bupropion, varenicline) should be used to enhance treatment efficacy.

Participants should be discouraged from using alternative nicotine products (heated tobacco, electronic cigarettes, nicotine pouches, etc.) due to the lack of their confirmed effectiveness, and the risk of maintaining nicotine addiction or returning to traditional smoking.

Each LCS center should develop its own evidence-based protocol for managing smoking cessation tailored to the needs of its population. The implemented intervention strategies should be systematically documented as a formal part of the LCS program records to ensure consistency and accountability in patient care.

Discussion

Every second screenee undergoing LCS actively uses tobacco. The question is not whether to provide cessation services within LCS but how to implement them effectively. An effective intervention must be scalable to facilitate widespread implementation [47]. This consensus statement represents the first comprehensive effort to address the issue of smoking cessation within LCS in Poland.

The analysis conducted in this study highlights the effectiveness of various smoking cessation methods, including behavioral interventions, pharmacotherapy, and combined approaches in improving quit rates among high-risk individuals. Our findings underscore the importance of a multifaceted approach, which not only supports patients in quitting smoking but also increases the overall success of LCS programs. This study paves the way for the implementation of more effective cessation strategies in the Polish healthcare system, ultimately aiming to improve patient outcomes and reduce lung cancer burden. This effort may be proposed as a pilot multifaceted smoking cessation program aiming at a universal Polish interventional smoking cessation product.

These guidelines emphasize the importance of providing targeted support to both current and potential smokers. By offering anti-smoking advice and referrals to specialized clinics, the program aims to reach individuals who still require assistance. For LCS participants, a thorough assessment and biochemical smoking validation provide accurate identification of smoking habits. The integration of cognitive-behavioral counseling and pharmacotherapy provides a holistic approach to smoking cessation, while educational materials prepare patients for the quitting process. Proactive monitoring and follow-up visits, along with active outreach for non-attendees, provide ongoing support. Teleconsultations offer additional flexibility, and the use of proven pharmacotherapies improves treatment outcomes. As cytisine is widely available over the counter or by prescription in Poland, it is a practical first-line option, especially where cost is a barrier [54]. Its efficacy is comparable to varenicline and superior to NRT, with a favorable safety profile [55]. The recommendation against alternative nicotine products is based on the insufficient evidence of efficacy and the potential risk of maintaining nicotine addiction, which may lead to a relapse to traditional smoking.

Our findings are consistent with major international guidelines developed by recognized organizations such as United States Preventive Services Taskforce (USPSTF) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which emphasize the inclusion of smoking cessation interventions directly into LCS programs. The USPSTF highlights the importance of shared decision-making in LDCT screening, balancing potential benefits with harms such as false positives, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure. The World Health Organization (WHO), while not developing universal recommendations, encourages countries to consider LDCT screening for high-risk groups where it is feasible and cost-effective, provided that screening is linked with robust cessation support. Our recommendations emphasize comprehensive, evidence-based support that combines behavioral counseling, pharmacotherapy, and proactive follow-up.

Despite the benefits of integrating smoking cessation into LDCT screening, several challenges must be acknowledged. Poland has a limited healthcare infrastructure and workforce, such as fewer CT scanners and physicians per capita compared to OECD averages, which can restrict access, especially in rural areas [56]. Moreover, limited healthcare funding and a lack of reimbursement for pharmacotherapies may hinder large-scale implementation of LCS. Furthermore, sustaining abstinence remains difficult, as relapse rates after quitting often exceed 70% within the first year [57], whereas the availability of smoking cessation clinics, which could provide long-term support through follow-up visits, is low and uneven across regions in Poland.

The feasibility of these recommendations depends on effective integration with the existing healthcare system in Poland. The LCS centers could serve as the central points for providing brief advice, initiating pharmacotherapy, and coordinating follow-up interventions, supported by standard national protocols and telemedicine tools. Close collaboration with primary care would support long-term abstinence. National policy measures, especially reimbursement for substance use treatment and professional training, are essential to ensure sustainability.

This consensus statement is not intended to serve as a clinical practice guideline or a legal standard of care and should not be treated as such. It is designed as a general guide consistent with sound healthcare practices. The specifics of individual treatment should be tailored to the unique details and circumstances of each participant.

There are several limitations associated with the Polish consensus on smoking cessation within LCS. These include possible differences in how cessation interventions are implemented across various regions, difficulties in ensuring long-term smoking cessation among participants, and the necessity for the program to be continuously updated with new evidence and practices. Finally, the successful integration of behavioral and pharmacological support hinges on proper training for healthcare providers and the availability of adequate resources, which may not always be guaranteed.

Conclusions

The Polish expert panel concludes that providing active smoking cessation support for all individuals undergoing lung cancer screening (LCS) is essential and should become standard practice. Integrating cessation into the screening process leverages the “teachable moment” when participants are especially motivated to quit, thereby maximizing the preventive benefit of LCS and improving overall health outcomes. A successfully implemented multifaceted cessation program within LCS could also serve as a model for incorporating tobacco treatment across other areas of healthcare in Poland.

For effective implementation, we recommend a comprehensive approach. Each LCS participant should receive clear educational materials, personalized counseling (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy), and appropriate pharmacotherapy (such as nicotine replacement therapy or varenicline) to maximize their chances of quitting. Regular follow-up, including scheduled check-ins or telemedicine consultations, and biochemical validation of abstinence (e.g., exhaled carbon monoxide or cotinine testing) are advised to help sustain long-term success and provide accountability. Participants should also be advised to avoid substituting cigarettes with other nicotine products like e-cigarettes or heated tobacco, as these alternatives lack proven cessation benefits and carry their own health risks.