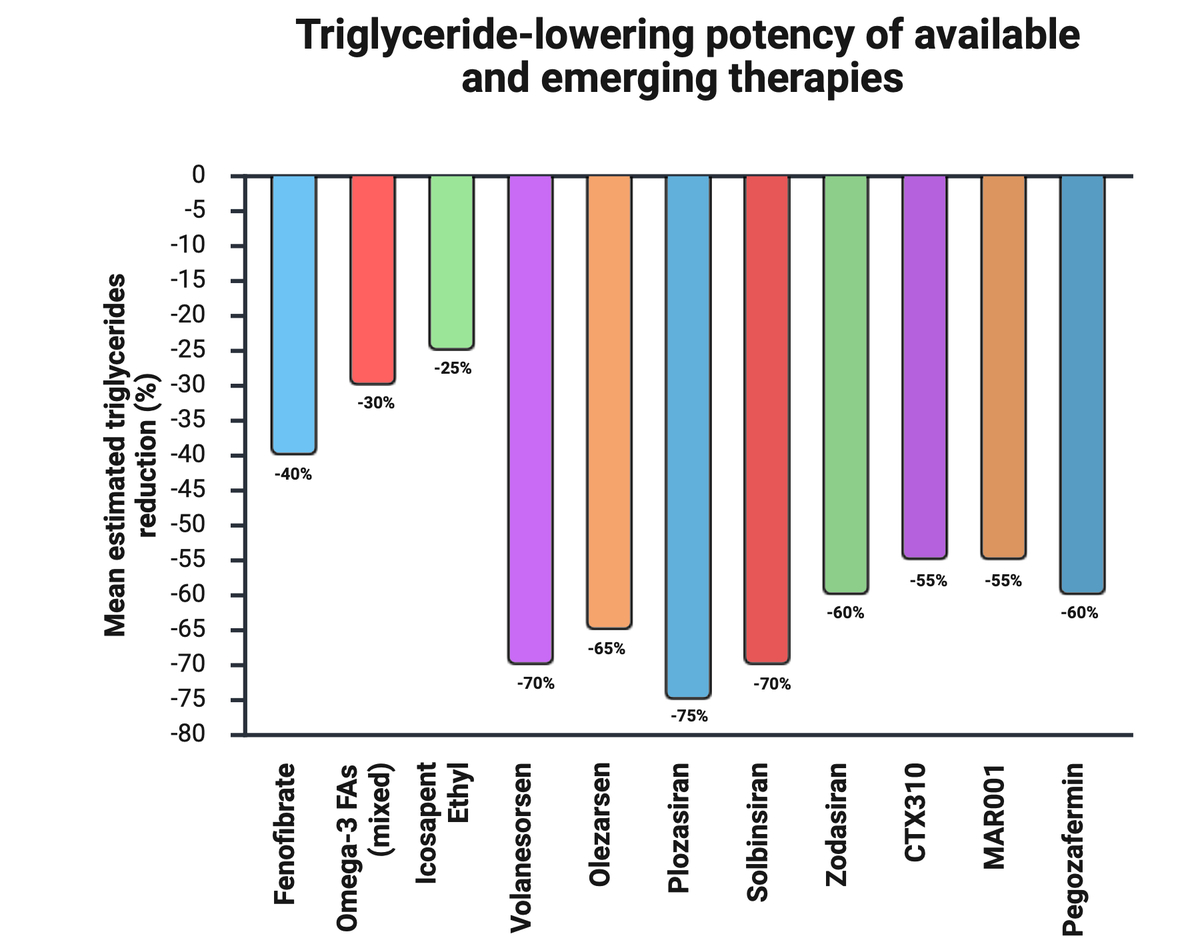

Triglyceride lowering agents

Hypertriglyceridemia

Hypertriglyceridemia (HTG) has a global prevalence of approximately 28.8% and it is increasing [1, 2]. It is a defining feature of the metabolic syndrome and is commonly encountered in the clinical settings of obesity, diabetes and chronic kidney disease [2]. Based on the National and Health Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), more than 25% of all US adults (56.9 million individuals) have triglycerides (TG) levels ≥ 150 mg/dl, including 31.6% (12.3 million) of those already being treated with statins [3]. The International Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events (INTERASPIRE) study showed that 32.6% of patients had HTG during the year following a myocardial infarction (MI) [4]. Mendelian randomization and genome wide association studies (GWAS) confirm that TG are causal in the atherogenesis pathway [5–8]. A large number of prospective longitudinal cohorts from around the world also support the finding that TG are an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) [9–15].

A meta-analysis of 29 Western prospective cohorts found that elevated TGs correlate with an increased risk for ASCVD with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 1.72 (95% CI: 1.56 to 1.90) [16]. A post hoc analysis of the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy (PROVE-IT) showed that even when low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is below 70 mg/dl (1.8 mmol/l), a TG level of ≥ 200 mg/dl (≥ 2.3 mg/dl) is associated with a 40% greater risk of major acute cardiovascular events (MACE) compared to patients with TG < 200 mg/dl (< 2.3 mmol/l) [17]. It has also been shown that there is a rising gradient of cardiovascular risk as triglycerides increase in both the short- and long-term as shown in the Myocardial Ischemia Reduction with Aggressive Cholesterol Lowering (MIRACL) with atorvastatin and Dal-OUTCOMES with dalcetrapib studies, respectively [18]. When comparing an elevated TG cohort (≥ 150 mg/dl [≥ 1.7 mmol/l]) to a propensity score (PSM) matched cohort with TG levels less than 150 mg/dl (< 1.7 mmol/l) (both groups with 23,181 participants), over a mean follow-up of approximately 42 months, among multivariate analysis revealed a significantly greater risk of composite major CV events (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.26; 95% CI: 1.19–1.34; p < 0.001), nonfatal MI (HR = 1.32; 95% CI: 1.20–1.45; p < 0.001), non-fatal stroke (HR = 1.14; 95% CI: 1.04–1.24; p = 0.004), and need for coronary revascularization (HR = 1.46; 95% CI: 1.33–1.61; p < 0.001) among those with TG ≥ 150 mg/dl [19].

Chylomicrons and their remnants are generally not seen as being atherogenic because they are structurally too large to undergo endothelial transcytosis. However, a large corpus of evidence has accumulated in the last decade supporting the observation that remnant apoB containing lipoproteins (e.g., small very low-density lipoproteins [VLDL] and intermediate density lipoproteins [IDL]) are atherogenic [20–23]. These lipoproteins carry significantly more cholesterol and other lipid into plaque per particle compared to LDL [24]. However, the triglyceride mass in LDL also associates with risk for ASCVD [21]. Remnant lipoproteins are more inflammatory than LDLs [25]. Moderate hypertriglyceridemic states also associate with proinflammatory transcriptomes by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [26]. This results that HTG is associated with endothelial dysfunction. HTG increases intravascular oxidative tone by activating NADH/NADPH oxidase yielding reactive oxygen species (ROS), augments intravascular inflammation by activating nuclear factor KB which promotes increased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1) and cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β), and is associated with formation of endothelial microparticles, a sign of endothelial distress [27–29]. Variants in numerous genes impact underlying risk for genetic HTG and ASCVD.

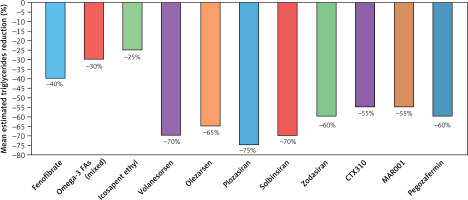

HTG alters the dynamics of lipoprotein physiology and gives rise to the so-called atherogenic “lipid triad”, characterized by large numbers of small, dense LDL particles, low HDL-C, and increased TG and triglyceride rich lipoproteins (TRLs; VLDL, small VLDL, and IDL) [30] (Figure 1). Secondary to impaired hepatic clearance of TRLs, there is an alternate mechanism to offload TG. Cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) is an enzyme that catalyzes the stoichiometric 1 : 1 exchange of cholesterol out of HDL and LDL particles for TG from TRLs. This enriches the HDL and LDL particles with TG and renders them better substrates for lipolysis by hepatic lipase. The LDL particles are converted into smaller, denser, more atherogenic particles, and the HDLs are catabolized and eliminated via renal pathways (megalin and cubilin binding) [31].

Figure 1

Hypertriglyceridemia and development of atherogenic dyslipidemia. When lipoprotein lipase activity is impaired, metabolic alterations occur in the process of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins to facilitate their catabolism in serum. CETP and hepatic lipase are activated which leads to the progressive loading of triglyceride into LDL and HDL particles. These lipoproteins are then lipolyzed by hepatic lipase resulting in the formation of both small, dense LDL (sdLDL) and small HDL (sdHDL) particles. The sdLDL particles become more numerous; the sdHDL particles are catabolized and liberated apoAI binds to cubilin and megalin in the glomerular ultrafiltrate and is eliminated, resulting in low serum levels of HDL-C. Based on Miller M et al. Circulation 2011; 123: 2292-2333

CE – cholesteryl ester, CETP – ester transfer protein, FFA – free fatty acid, sdHDL – small – dense high-density lipoprotein, sdLDL – small – dense low-density lipoprotein, TG – triglyceride, VLDL – very low-density lipoprotein.

Fenofibrate

Fenofibrate is a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α (PPAR-α) activator. PPAR-α is a nuclear transcription factor that activates the expression of numerous genes involved in triglyceride and lipoprotein metabolism [32]. Its natural occurring ligands include arachidonic acid and its metabolites. Fenofibrate increases the expression of lipoprotein lipase (LL) and leads to increased hydrolysis of TGs within chylomicrons and VLDLs. ApoCII and apoA5 are important activators of LL and plasma levels of both are increased by fenofibrate [33, 34]. Fenofibrate increases hepatic expression of apoAI and apoAII, thereby augmenting the hepatic biogenesis of HDLs. Adjunctive to HDL raising, fenofibrate reduces CETP activity, reducing rates of HDL catabolism [35]. In addition to promoting triglyceride hydrolysis, fenofibrate increases rates of mitochondrial fatty acid uptake and metabolism by upregulating the expression of carnitine palmitoyl transferase I (CPTI) and the enzymatic apparatus of mitochondrial beta-oxidation (e.g., acyl Co oxidase). Another important effect of fenofibrate is its capacity to downregulate the expression of apoCIII [36]. ApoCIII is an inhibitor of LL; it displaces apoCII and induces steric hindrance of the enzyme’s active site. In addition, apoCIII impairs the uptake of chylomicron remnants and other triglyceride enriched lipoproteins by two mechanisms: (1) it displaces apoE, which impairs binding of the lipoprotein to a lipoprotein receptor, and (2) it downregulates the expression of the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R) and LDL-like receptor related protein (LDL-RP) along the hepatocyte surface [37].

The FIELD (Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes) trial randomized 9795 type 2 diabetic participants to either placebo or fenofibrate therapy (once-daily micronized fenofibrate 200 mg) over a mean follow-up period of 5 years [38]. The study was confounded by excess statin “drop in” in the fenofibrate treatment arm compared to placebo (after the Heart Protection Study [HPS] being published). Fenofibrate significantly reduced TGs by 29% (and apoB by 13.6%) what resulted in nonsignificant reduction of the primary composite endpoint of nonfatal MI and coronary heart disease (CHD) related death by 11% (HR) 0.89 (95% CI: 0.75–1.05; p = 0.16). This included a significant 24% reduction in non-fatal MI (HR) 0.76 (0.62–0.94; p = 0·010) and a non-significant changes in CHD mortality (1.19, 0.90–1.57; p = 0.22). Total cardiovascular disease events were significantly reduced by 11% (p = 0.035) and there was a 21% reduction in coronary revascularization (p = 0.003) [38]. Importantly, after adjusting the results to statin/non-study drug lipid lowering therapy in both arms (17% in the placebo group and 8% in the fenofibrate group; p < 0.0001) fenofibrate significantly reduced the primary endpoint by 19% (p = 0.01). Fenofibrate therapy also significantly reduced all cardiovascular events in the subgroup (n = 2,014) of patients with elevated TG + low HDL-C (by 25%; p = 0.005) [39, 40]. Of significant interest were the findings on the important role of the fenofibrate in micro- and macrovascular complications, including: (1) the need for laser photocoagulation for proliferative retinopathy by 30% (p = 0.002) and development of macular edema by 31% (p = 0.002) [41], amputation of the toe or foot by 46% (p = 0.007) [4, 42], and development of albuminuria by 12% (p = 0.01) [43].

The ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) trial randomized 5,518 patients with type 2 diabetes and on background simvastatin therapy to receive either fenofibrate (160 mg/day or 54 mg/day in those with eGFR between 30 and < 50 ml/min/1.73 m2) or placebo and followed for 4.7 years [44]. It is worth emphasizing that patients in both groups were very well treated, with mean baseline TG levels of 164 mg/dl (1.85 mmol/l) and 160 mg/dl (1.8 mmol/l) in the fenofibrate and placebo groups, respectively – which, given current recommendations, would have precluded fenofibrate therapy in these patients [39, 40]. The primary composite outcome included nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes. Despite TG were reduced significantly by about 26% in the fenofibrate group, neither the primary outcomes nor any of the secondary outcomes were reduced by the addition of fenofibrate to simvastatin therapy. It was again observed that in the group of patients with atherogenic dyslipidemia (TG ≥ 204 mg/dl and HDL-C ≤ 34 mg/dl) fenofibrate reduced the risk of MACEs by 31% (p = 0.06). Consistent with the FIELD, the ACCORD Lipid trial demonstrated a 40% (p = 0.006) reduction in risk for diabetic retinopathy and micro- (aRR = 3.4%; p = 0.01) and macroalbuminuria (aRR = 1.8%; p = 0.04) occurrence [44].

The Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study (DAIS) trial included 731 men and women randomized to either fenofibrate therapy or placebo for approximately 3 years [45]. The fenofibrate treatment arm showed a significantly lower increase in percentage diameter stenosis than the placebo group (mean 2.11 [SE 0.594] vs. 3.65 [0.608]%, p = 0.02), a significantly smaller reduction in minimum lumen diameter (–0.06 [0.016] vs. –0.10 [0.016] mm, p = 0.029), and a non-significantly lower decrease in mean segment diameter (–0.06 [0.017] vs. –0.08 [0.018] mm, p = 0.171) compared to placebo, suggesting that fenofibrate is effective at slowing the rate of atherosclerotic plaque progression [45].

The FIELD and ACCORD main studies showed that fenofibrate significantly reduces progression and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. In the FIELD ophthalmologic subanalysis (n = 1,012 patients), fenofibrate cut the need for laser therapy by 31% (HR = 0.69; 95% CI: 0.56–0.84; p = 0.0002), reduced cumulative laser procedures by 37% (p = 0.0003), and lowered risk of significant retinal pathology (≥ 2-step progression, macular oedema, or laser) by 34% (p = 0.022). Benefits were largest in patients without prior retinopathy (49% reduction) and in preventing first laser therapy (79% reduction). These effects were not explained by changes in HbA1c, concomitant treatments, or small BP differences [46]. The ACCORD-EYE study (n = 1,593 patients) found that adding fenofibrate to a statin significantly reduced retinopathy progression by 40% vs statin alone (OR = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.42–0.87; p = 0.006), with benefit seen in patients with existing retinopathy, and this effect was independent of effective control of LDL (78 mg/dl), glycemia (HbA1c 6.4–7.5%) and blood pressure (129/68 mm Hg) [47]. Importantly, large observational and pooled analyses supported these findings: a study of 65,586 patients found lower risk of retinopathy endpoints with statin plus fenofibrate versus statin alone (HR = 0.88, 95% CI: 0.81–0.96), with significant effects in those with pre-existing retinopathy [48]. A 2022 meta-analysis of the FIELD, ACCORD and the Lipids in Diabetes Study (LDS) (n = 1,504) showed a 30% reduction in laser treatment at 1 year (OR = 0.70, 95% CI: 0.58–0.83) and 23% at any time (0.77, 95% CI: 0.67–0.88) with fenofibrate [49]. Meer et al. reported an 8% (HR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.87–0.98) reduced the risk of progression of progression of non-proliferative retinopathy to sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy (STDR) and 24% (0.76; 95% CI: 0.64–0.90) reduced risk of proliferative retinopathy with fenofibrate [50]. Finally, the 2024 LENS (Lowering Events in Non-proliferative retinopathy in Scotland) trial (n = 1,151 patients) found a 27% lower risk of a primary endpoint involving the development of treatable diabetic retinopathy or maculopathy or treatment of retinopathy or maculopathy (vitreous injections, laser therapy, vitrectomy) after 4 years (HR = 0.73; 95% CI: 0.58–0.91; NNT = 15), with significant reductions in any progression of retinopathy or maculopathy (by 26%) and diabetic macular oedema (by 50%) with fenofibrate 145 mg/day. Benefits were greater in women, those with CKD, better baseline glycaemic control, and with longer fenofibrate exposure [51]. Based on these results, some countries have extended (or applied to extend) fenofibrate indications for patients with diabetes and retinopathy. The Polish Lipid Association (PoLA) issued a Consensus Statement recommending that, in type 2 diabetes, adding fenofibrate to statin therapy may be considered for patients with persistent TG > 150 mg/dl (1.7 mmol/l) to reduce micro- and macroangiopathic complications (IIa B). Specifically, fenofibrate added to statin therapy may be considered to reduce the risk of retinopathy (IIb B), and, when retinopathy is present, adding fenofibrate to statin therapy is recommended to reduce retinopathy progression, need for ocular surgery, and risk of vision loss (I B) [52].

Clearly, in the FIELD trial, fenofibrate demonstrated some capacity to reduce hard cardiovascular endpoints. In fact, had FIELD included nonfatal stroke in its primary composite endpoint, it would have been a positive study. As mentioned above, fenofibrate has particular value for reducing microvascular disease. Based on DAIS it also slows the rate of ASCVD progression. It can be used reliably to reduce serum TG either as monotherapy or when used in combination with a statin. Although gemfibrozil (not available on many European markets) reduces risk for acute cardiovascular events in both the primary [53] and secondary [54] prevention settings, it is generally not safe to take this medication in combination with a statin. This is important to emphasize since patients with severe HTG frequently require a statin in order to not only provide incremental triglyceride reduction but also reduce elevations in LDL-C resulting from increased LL activity. Gemfibrozil and its metabolites significantly inhibit CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 [55]. Gemfibrozil also reduces the glucuronidation of statins (inhibits multiple UDP-dependent glucuronosyltransferases), which decreases their elimination [56]. Fenofibrate is substantially safer to use in combination with the statins since, what was also confirmed in the ACCORD trial [44], as it does not impair statin glucuronidation [57, 58].

The Pemafibrate to Reduce Cardiovascular Outcomes by Reducing Triglycerides in Patients with Diabetes (PROMINENT) trial was specifically designed to address the issue of efficacy and safety of fibrates in a prospective, randomized manner in 10,497 participants [59]. Patients with type 2 diabetes, HTG (200 to 499 mg/dl), and HDL-C (≤ 40 mg/dl) or lower were randomized to receive pemafibrate (0.2 mg tablets twice daily) or placebo. Participants were on background statin therapy and median follow-up was 3.4 years. No benefit was discerned in either the primary composite endpoint or any secondary endpoint despite the fact that pemafibrate reduced triglycerides 26.2%, VLDL 25.8%, remnant lipoprotein cholesterol 25.6%, and apo CIII by 27.6%. The potential benefit of these changes was offset by a 4.8% increase in apoB (and LDL-C increase by 12%). The trial was terminated early by the study’s data safety and monitoring board because prespecified futility boundaries were crossed. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the two study groups were superimposable [59]. Unfortunately, some experts have unjustifiably generalized these findings to all fibrates, claiming an end to the era of fibrates for reducing residual CVD risk – a position that contradicts existing data and may be harmful in everyday clinical practice [52].

Omega-3 fatty acids

Fish oil capsules are enriched with omega-3 (eicosapentaenoic acid – EPA; docosahexaenoic acid – DHA) polyunsaturated fatty acids (FAs). The n-3 FAs perform the following lipid related functions: (1) reduce serum triglyceride (by about 35% in monotherapy and 25% added to statin therapy) and VLDL levels in a dose dependent manner; (2) inhibit the enzyme diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2, thereby reducing intrahepatic triglyceride biosynthesis; (3) stimulate mitochondrial β-oxidation of fatty acids, decrease VLDL production and biosynthesis; (4) and stimulate triglyceride hydrolysis by LL [60, 61]. These long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and their metabolites are natural agonists of PPAR-α and PPAR-γ and hence they play roles in lipid/lipoprotein and glucose metabolism [60]. The omega-fatty acids are anti-inflammatory as they potentiate the production of a variety of resolvins (EPA, E-series; DHA, D-series), protectins, and maresins, endogenous agents that bring inflammation to an orderly conclusion [62–65]. They have been shown to reduce serum levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) (by 20–38%), lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 (by 12–14%), and tumor necrosis factor-α, among others, and boost levels of IL-10, a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine [64–68]. EPA and DHA also have the capacity to disrupt cell membrane lipid rafts (thereby interfering with the transmission of proinflammatory signals into the cell), inhibit nuclear factor KB (a proinflammatory nuclear transcription factor), downregulate oxidative enzymes such as NADPH oxidase, upregulate anti-oxidative enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and modulate cell membrane fluidity, among other functions [66, 68].

Dietary supplementation with the n-3 PUFAs, EPA and DHA has been shown to significantly lower the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality after MI in the GISSI-Prevenzione trial: Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico [69]. These benefits were observed independent of any changes in serum lipids. In a subsequent analysis it was shown that survival curves for n-3 PUFA treatment separated remarkably early after treatment randomization [70]. All-cause mortality was significantly lowered after 3 months of treatment (relative risk [RR] = 0.59; 95% CI: 0.36–0.97; p = 0.037); the reduction in risk of sudden death was significant after only 4 months (RR = 0.47; 95% CI: 0.219–0.995; p = 0.048). This trial was done before the contemporary statin era [70]. Since the GISSI trial, no other study evaluating the combination of EPA and DHA has been able to demonstrate any cardiovascular benefit. This was most recently shown by such studies as ASCEND (A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes) [71], STRENGTH (Long-Term Outcomes Study to Assess Statin Residual Risk with Epanova in High Cardiovascular Risk Patients with Hypertriglyceridemia) [72], OMEMI (Omega-3 fatty acids in Elderly with Myocardial Infarction) [73] and VITAL (Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial) trials [74]. In a meta-analysis that included 57,764 participants, it was shown that combination EPA/DHA supplementation provided no benefit for preventing CVD in persons with diabetes [75]. In another meta-analysis of 127,477 participants demonstrated that omega-3 PUFA supplementation correlated with modest but significantly lower risks for MI (RR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.86–0.99; p = 0.020), CHD mortality (0.92, 95% CI: 0.86–0.98; p = 0.014), total CHD (0.95, 95% CI: 0.91–0.99; p = 0.008), CVD mortality (0.93, 95% CI: 0.88–0.99; p = 0.013), and total CVD (0.97, 95% CI: 0.94–0.99; p = 0.015) [76]. A meta-analysis by Khan et al. (n = 149,051) showed similar findings for EPA/DHA supplementation, with estimated risk reductions as follows: CVD mortality (0.94 [0.89–0.99]), non-fatal MI 0.92 [0.85–1.00]), CHD events 0.94 [0.89–0.99]) [77]. Such findings have yet to be confirmed in a prospective randomized clinical trial. Hence, combination EPA/DHA therapy is not recommended for reducing CVD risk in the setting of HTG.

Clinical trial results with EPA monotherapy have turned out to be more straightforward. The Japan EPA Lipid Intervention Study (JELIS) evaluated whether or not the addition of fish oils to patients already taking a statin would provide incremental risk reduction. Approximately 19,000 Japanese men and women with hypercholesterolemia were prospectively randomized to statin therapy with or without 1800 mg/day of EPA [78]. Combination therapy resulted in an additional 19% reduction in major coronary events at 4.6 years of follow up compared to statin monotherapy [78]. The Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl–Intervention Trial (REDUCE-IT) evaluated the impact of treating patients with established ASCVD and high risk diabetic patients already on a statin with 4.0 g of highly purified EPA (icosapent ethyl) daily [79]. Patients had baseline triglyceride levels of 135–499 mg/dl (1.5–5.6 mmol/l). A total of 8179 participants were randomized and followed for a median of 4.9 years. The primary composite endpoint included CVD death, nonfatal MI (including silent MI), nonfatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or unstable angina in a time-to-event analysis. The secondary composite endpoint included cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke in a time-to-event analysis. The median TG reduction from baseline was 19.7%, LDL-C increased by 3.1% and apoB declined by 2.5%. Both the primary (HR = 0.75; 95% CI: 0.68–0.83; p < 0.001); and secondary (0.74; 95% CI: 0.65–0.83; p < 0.001) endpoints were reduced significantly. A number of prespecified secondary endpoints were also reduced significantly: (1) fatal or notal MI (0.69 (0.58–0.81); p < 0.001), (2) urgent or emergent revascularization (0.65 (0.55–0.78); p < 0.001), (3) cardiovascular death (0.80; 95% (0.66–0.98); p = 0.03), (4) hospitalization for unstable angina (0.68 (0.53–0.87); p = 0.002); (5) fatal or nonfatal stroke (0.72 (0.55–0.93); p = 0.01). Key prespecified tertiary endpoints included adjudicated sudden cardiac death (0.69; 0.50–0.96), and cardiac arrest (0.52; 0.31–0.86). A larger percentage of patients in the icosapent ethyl group than in the placebo group were hospitalized for atrial fibrillation or flutter (3.1% vs. 2.1%, p = 0.004). Both the STRENGTH (NOAF was observed in 2.2% in the omega-3 group and 1.3% in placebo group; HR = 1.69; p < 0.001; NNH = 114) [72] and OMEMI (7.2% in omega-3 group vs. 4.0% in placebo group; HR = 1.84, 0.98–3.45; p = 0.06) [73] trials also showed significant elevations in risk for atrial fibrillation. However, in REDUCE-IT, as indicated above, risk for stroke was reduced. Serious bleeding events occurred in 2.7% of the patients in the icosapent ethyl group and in 2.1% in the placebo group (p = 0.06). The latter observation is most likely explained by the antiplatelet effects of EPA, possibly mediated by the oxylipin metabolite of EPA (12-HEPE) [80]. In contrast, the JELIS trial – which did not evaluate atrial fibrillation – showed no significant stroke reduction and a higher incidence of bleeding events (cerebral, retinal, epistaxis, subcutaneous): 1.1% in the EPA group versus 0.6% with placebo (p = 0.006) [78]. Benefit of IPE in the REDUCE-IT was independent of serum triglyceride levels. Icosapent ethyl is indicated to reduce the risk of acute cardiovascular events in adults with high TG (≥ 150 mg/dl [1.7 mmol/l]) with very high CVD risk of either established ASCVD or have DM with at least two other risk factors. It is also indicated as adjunct to diet and exercise to lower very high triglyceride levels (≥ 500 mg/dl) in adults. No clinical outcomes trials have ever been done with DHA monotherapy. Hence, it is unknown how this molecule may attenuate or even negate the benefit of EPA therapy; RCTs on α-linolenic acid (ALA) – the plant-based precursor of EPA and DHA – are likewise lacking.

Apolipoprotein CIII Inhibitors

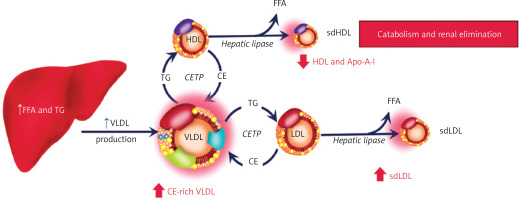

LL is an enzyme that is positioned at the epicenter of physiology to process and help distribute oxidizable substrate (free fatty acids) to nearly all cell types. It is tethered to the luminal aspect of capillary endothelial cells by glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein binding protein 1 (GPIHBP-1) [81, 82]. In addition to its activity being regulated by the C apoproteins (apoC1 and apoCIII are inhibitors, apo CII is an activator) and apoA5, LL activity depends on multiple other biochemical influences (Figure 2). During processing within the endoplasmic reticulum, lipase maturation factor-1 (LMF-1) is responsible for promoting the proper conformational folding and assembly of LL monomers into head-to-tail dimers [83]. LL monomers are not catalytically active; they must be dimerized prior to secretion from the endoplasmic reticulum in order to be lipolytically active. Angiopoietin-like protein 4 (a ANGPTL-4) catalyzes a conformational change in LL leading to the dissociation and inactivation of its subunits [84, 85]. The dimer of angiopoietin-like proteins 3 and 8 (ANGPTL-3/8) functions as an inhibitor of LL [86]. The phosphorylated carboxyl-terminal fragment of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate–responsive element-binding protein, hepatic-specific) (CREBH-C) blocks the formation of angptl-3/8 and increases LL activity [87]. Insulin, catecholamines, and thyroid hormone also activate LL [88].

Figure 2

Highly schematic depiction of lipoprotein lipase and its regulation. Lipoprotein lipase is comprised of two identical subunits comprising a homodimer in a head to tail topology whose conformation is stabilized by 5 disulfide bonds as well as hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. There is a hydrophobic pore next to the active site allowing for the release of free fatty acid. True views of the enzyme based on crystallography and microscopy are available. Based on: Gunn KH et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020; 117: 10254-64, Birrane G et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019; 116: 1723-32

apo – apoprotein, CREBH-C – carboxylterminal fragment of cyclic adenosine 3′ –5′-monophosphate–responsive element-binding protein – hepatic-specific, GPIHBP-1 – glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored high-density lipoprotein binding protein-1, LMF-1 – lipase maturation factor-1.

Patients afflicted with Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (FCS) typically have TG > 880 mg/dl (10 mmol/l) and are at increased risk for recurrent pancreatitis [89, 90]. These patients have severely reduced or no LL activity. It typically has a monogenic etiology attributable to biallelic loss of function variants in the genes for LL (80%) or positive regulators of this enzyme (GPIHBP1, ApoC2, ApoA5, and LMF1; 20%) [91]. Symptoms often develop at an early age with failure to thrive, chronic abdominal pain, hepatosplenomegaly, lipemia retinalis, eruptive xanthomas, and pancreatitis [92, 93]. Depending on the area studied, it has a population frequency of 1–19/1,000.000 [94]. Serum from these patients is lipemic and adults may complain of cognitive impairment, eating disorders, severe fatigue, diabetes secondary to loss of pancreatic islet cell mass from recurrent pancreatitis, and depression [95].

Although chylomicron and triglyceride-enriched lipoprotein clearance is severely impaired in patients with FCS, other aspects of their lipid/lipoprotein metabolism remain intact, making life possible and ensuring that triglyceride levels do not simply keep rising indefinitely (Figure 3). Cholesterol esters and TG delivered back to the liver by LDL particles are hydrolyzed by lysosomal acid lipase (LAL). Adipose tissue lipases (hormone sensitive lipase and adipose tissue lipase) continue to release FFA into the circulation. Phospholipases and monoacylglycerol and diacylglycerol lipases continue to engage in the metabolism of phospholipids and mono- and diglycerides, respectively. Hepatic lipase and endothelial lipase continue to remodel lipoproteins and hydrolyze a percentage of triglyceride mass in serum [95].

Figure 3

Triglyceride metabolism scheme. When lipoprotein lipase activity is either inhibited or functionally severely impaired, lipoprotein (chylomicrons, VLDL and remnant lipoproteins) triglycerides are not hydrolyzed efficiently in serum. However, other enzymes continue to lipolyze triglycerides and can release fatty acids from cholesterol esters. In serum, endothelial lipase and hepatic lipase have the capacity to hydrolyze triglycerides. In adipose tissue, both hormone sensitive lipase and adipose triglyceride lipase work in a complementary manner to liberate fatty acids from stored triglyceride. In the gut pancreatic lipase can hydrolyze triglycerides for enterocyte absorption of free fatty acids. Within cells, phospholipases, diacylglycerol and monoglycerol lipases, and lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) participate in triglyceride metabolism. LAL also hydrolyzes cholesterol esters to liberate fatty acid

Until recently, the management of FCS was difficult, burdensome, and complex for patients. Even in a fasting state their serum has the appearance of “heavy cream” (lipemic blood) due to the massive elevation of TG. Restricting total fat intake to < 10–15% of total caloric intake and use of medium chain fatty acid (MCFA; C8-C10) oils can be challenging. In FCS, medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oils provide calories and some fat without worsening chylomicronemia because caprylic (C8) and capric (C10) acids are absorbed via the portal vein and do not require lipoprotein lipase (LPL). The usual target MCT intake is 30–45 g/day (≈270–405 kcal), titrated to tolerance and adjusted individually by a registered dietitian nutritionist [90–95].

Standard lipid-lowering medications tend to provide inadequate triglyceride lowering efficacy. Two new therapies for this rare disease are now available and are used to inhibit the hepatic production of apoCIII. Both are conjugated with triantennary N-acetylgalactosamine (tri-GalNAc) that can bind to asialoglycoprotein receptors (ASGPRs) on the surface of hepatocytes and be taken up by the endosomal pathway [96, 97]. This allows for fairly specific uptake by the liver with minimal clearance by other organs. Olezarsen is an anti-sense oligonucleotide (ASO) that binds to apoCIII mRNA [98]. The complex formed is then hydrolyzed by RNase H1. RNA silencing is an ancient cellular approach to regulating the expression of genes and their mRNA [99]. Plozasiran is a double-stranded small interfering RNA (siRNA) that is comprised of both a passenger and guide strand [100]. Once inside a hepatocyte, the passenger strand is hydrolyzed on an RNA-induced silencing complex; the guide strand then anneals to apoCIII mRNA, and it is catabolized. Both of these agents are injected subcutaneously, provide dramatic reductions in both apoCIII and TG, and have proven efficacy for reducing risk of pancreatitis.

Before discussing new strategies for inhibiting apoC-III, the effects of the currently marketed apoC-III inhibitor, volanesorsen, should be reviewed in detail. Volanesorsen, an ASO targeting apoC-III mRNA, represents a pioneering therapy for FCS, already available on the market and just included in the recent European guidelines [101]. The phase 3 APPROACH trial (NCT02211209) randomized 66 FCS patients to weekly subcutaneous volanesorsen (300 mg) or placebo for 3 months, followed by extension phases [102]. The primary endpoint in the study was TG percent change from baseline (mean ~2200 mg/dl [25 mmol/l]). Volanesorsen achieved a 77% TG reduction (mean absolute reduction of 1712 mg/dl) vs. +18% increase with placebo (p < 0.001); 77% FCS patients reached TG < 750 mg/dl vs. 10% in the placebo group [102]. Sustained effects of volanesorsen were observed in the open-label extensions: 48–66% TG reductions at 3–24 months across APPROACH, COMPASS (multifactorial chylomicronemia), and treatment-naïve cohorts [103]. The phase 3 COMPASS trial (NCT02300233) in multifactorial chylomicronemia showed 71.2% TG reduction (869 mg/dl absolute reduction) vs. +0.9% placebo at 3 months (p < 0.0001), with potential pancreatitis risk reduction. Quality-of-life improvements, including reduced abdominal pain and fatigue, correlated with TG drops [104]. The subsequent meta-analysis of available data confirmed that volanesorsen was associated with significant reduction of acute pancreatitis (AP) risk – 2% (2/121) in the volanesorsen group vs. 10% (9/86) for placebo (OR = 0.18; 95% CI: 0.04–0.82) [105]. Volanesorsen was approved in Europe by EMA in 2019 for adult FCS patients at high pancreatitis risk, despite diet/standard therapy failure (adjunctive use requires certified centers), in the US it is still not FDA-approved; approval pending/withdrawn post-approval studies due to thrombocytopenia/hepatotoxicity risks. Based on the recent ESC/EAS 2025 updated guidelines, volanesorsen (300 mg/week) should be considered in patients with severe HTG (> 750 mg/dl, > 8.5 mmol/l) due to familial chylomicronemia syndrome, to lower triglyceride levels and reduce the risk of pancreatitis (IIa B) [101].

The efficacy of olezarsen and plozasiran has been investigated in randomized, placebo controlled trials. In A Study of Olezarsen Administered to Patients With Familial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (BALANCE), 66 patients with genetically confirmed FCS (homozygous or heterozygous compound loss function mutations in the genes for LPL, apoC2, apoA5, LMF-1, or GPIHBP1) and fasting TG ≥ 880 mg/dl (≥ 10 mmol/l) were randomized to receive placebo or olezarsen at 50 or 80 mg monthly [106]. The baseline mean (±SD) triglyceride level for participants was 2630 ±1315 mg/dl; 71% had a history of acute pancreatitis in the preceding 10 years. After 6 months of therapy, placebo-adjusted triglyceride reductions were –22.4% (95% CI: –47.2 to 2.5; p = 0.08) with the 50 mg dose and –43.5% (95% CI: –69.1 to –17.9; p < 0.001) with the 80-mg dose. The mean percent change in apoC-III levels after 6 months of therapy were –65.6% (95% CI: –82.6 to –48.3) in the 50-mg group and –73.7% (95% CI: –94.6 to –52.8) in the 80 mg group. Risk for pancreatitis was reduced: after 53 weeks there were 11 cases of pancreatitis in the placebo group and 1 case in each olezarsen treatment groups (RR [pooled olezarsen groups vs. placebo] = 0.12; 95% CI: 0.02–0.66) [106]. In the PALISADE (a randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 study of plozasiran in patients with FCS) trial 75 patients with persistent chylomicronemia (median baseline triglyceride of 2044 mg/dl; with or without a genetic diagnosis) were randomized to treatment with plozasiran (25 mg or 50 mg) or placebo every 3 months for 12 months [100]. The primary end point was the placebo-adjusted median percent change in triglyceride levels at 10 months. After 10 months of therapy the median reduction in fasting triglyceride levels was –80% in the 25 mg plozasiran group, –78% in the 50 mg plozasiran group, and –17% in the placebo group (p < 0.001); apoC3 was reduced with median reductions of –93% in the 25 mg plozasiran group, –96% in the 50 mg plozasiran group, and –1% in the placebo group (p < 0.001). Multiplicity-controlled principal secondary endpoints include percent change in apoC3 at 10 and 12 months and the incidence of acute pancreatitis. The incidence of acute pancreatitis was reduced significantly (pooled plozasiran groups vs. placebo, 0.17; 95% CI: 0.03–0.94; p = 0.03) [100]. In the next analysis from the PALISADE trial the authors investigated the temporal effects of 25 mg plozasiran, the influence of genetic status on therapeutic responses, and the proportion of patients who attained guideline-recommended TG goals for reducing acute pancreatitis (AP) risk [107]. At least half the patients maintained TG levels below thresholds for preventing AP: 75% had TG < 880 mg/dl (10 mmol/l) and 50% had TG < 500 mg/dl (5.7 mmol/l), irrespective of FCS genotype. Plozasiran significantly decreased total cholesterol by –41.3% (95% CI: –60.1 to –22.6), non–HDL-C by –49.5% (95% CI: –70.3 to –28.7), and VLDL-C by –66.5% (95% CI: –92.0 to –41.0), and increased HDL-C by 51.9% (95% CI: 20.4–83.3) and apoA-I by 20.6% (95% CI: 8.6–32.7) at 12 months (all p < 0.001). Notably, despite effects on TG metabolism, plozasiran only slightly increased LDL-C concentration without changing total apoB or apoB100 concentrations; importantly, posttreatment LDL-C levels remained below the 55 mg/dl threshold associated with increased ASCVD risk. None of the lipid, lipoprotein, or apolipoprotein changes varied significantly by genotype [107].

Another form of severe HTG is multifactorial chylomicronemia syndrome (MCS). MCS has an incidence of 1 : 600 to 1 : 1250 and is thus much more common than FCS [108]. It is important to differentiate these two clinical entities, which is generally done by genetic characterization and clinical history. MCS has a polygenic etiology and is typically made manifest by changes in clinical status, such as the development of insulin resistance (obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes), excess alcohol intake, or initiation of medications that may antagonize insulin sensitivity (thiazide diuretics, β-blockers, steroids) and exacerbate the proclivity toward HTG [108]. Compared to a normolipidemic state, MCS augments risk for acute pancreatitis and ASCVD by approximately 7-fold and 2- to 9-fold, respectively [109–111]. MCS correlates with increased risk for ASCVD because it induces elevations in both chylomicrons and TG-enriched lipoproteins such as VLDL and IDL. It is type V hyperlipoproteinemia according to the Fredrickson-Levy classification [112]. In the LIPIGEN-sHTG (Lipid Transport Disorders Italian Genetic Network – Severe Hypertriglyceridemia) registry, the most commonly occurring loss of function mutations in MCS are found in the genes for LPL, APOA5, APOC2, LMF1, GPIHBP1, GPD1 (glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1), and CREB3L3 (cAMP responsive element-binding protein 3 like 3; an activator of FGF21 and LL) [113]. Among persons with MCS, the degree of DNA methylation in the SREBF1 (sterol regulatory element binding factor F1, an activator of lipogenesis) gene contributes to risk for ASCVD [114].

The CORE-TIMI 72a and CORE2-TIMI 72b trials evaluated the efficacy of olezarsen therapy in persons with severe HTG (≥ 500 mg/dl [5.7 mmol/l]) [115]. The median triglyceride level for the two trials was 793 mg/dl and 63.4% of participants had diabetes mellitus. After 6 months of treatment, the placebo-adjusted least-squares mean change from baseline in triglyceride levels were –62.9% in the olezarsen 50-mg group and –72.2% the olezarsen 80-mg group in the CORE-TIMI 72a trial, and –49.2% in the olezarsen 50-mg group and –54.5% in the olezarsen 80-mg group in the CORE2-TIMI 72b trial (p < 0.001 for all comparisons to placebo). Reductions in serum apoC-III, remnant lipoprotein cholesterol, and non-HDL-C were significantly greater with olezarsen compared to placebo (p < 0.001 for all comparisons). Olezarsen also increased both HDL-C and LDL-C, and modestly reduced apoB (7.3 and 8.7% in both trials). These resulted in significant lowered risk for acute pancreatitis (mean rate ratio = 0.15; 95% CI: 0.05–0.40; p < 0.001). 86% of AP events occurred among the patients who had baseline TG ≥ 880 mg/dl (10 mmol/l) and had a history of pancreatitis. In this high-risk subgroup olezarsen reduced the risk of AP by 83% in comparison to the placebo group (mean rate ratio = 0.17; 95% CI: 0.06–0.47) [115]. Magnetic resonance imaging performed at 12 months revealed a dose-dependent increase in hepatic fat with olezarsen, with a least squares mean absolute increase of 2.28% and 4.18% in the in the olezarsen 50-mg and 80-mg treatment groups, respectively. In contrast, in the placebo treatment group hepatic fat increased by 0.14% [115]. In another study with olezarsen (ESSENCE TIMI 73b trial) patients with moderate HTG (TG between 150 [1.7 mmol/l] to 499 mg/dl [5.6 mmol/l]) and elevated CVD risk or with SHTG (TG ≥ 500 mg/dl [5.7 mmol/l]) were randomly assigned to olezarsen therapy at doses of 50 or 80 mg [116]. The primary outcome was the mean percent change in TG level from baseline to 6 months. Finally 1349 patients were included (median age was 64 years, women 40%, median TG level at baseline was 238.5 mg/dl (2.7 mmol/l). At 6 months, the placebo-adjusted least-squares mean change in TG level was –58.4% (95% CI: –65.1 to –51.7; p < 0.001) for olezarsen 50 mg and –60.6% (95% CI: –67.1 to –54.0; p < 0.001) in the olezarsen 80 mg group. The incidence of serious adverse events was similar across the trial groups [116]. The FDA approved olezarsen on December 19, 2024, for adults with FCS as an adjunct to diet to reduce TG. This represents a first-in-class approval, meaning it uses a new mechanism of action different from existing therapies. Additionally, the FDA granted Breakthrough Therapy designation to olezarsen for treating adults with severe HTG with triglyceride levels ≥ 500 mg/dl (5.7 mmol/l). The EMA approved olezarsen on September 17, 2025, for adults with FCS. in the European Union.

In the Study to Evaluate ARO-APOC3 in Adults With Severe Hypertriglyceridemia (SHASTA-2) trial, participants with severe HTG (median triglyceride 897 mg/dl (10.1 mmol/l), 65% were diabetic) were randomized to receive either plozasiran or placebo and followed for 48 weeks [117]. Plozasiran therapy was associated with significant dose-dependent, placebo-adjusted least squares (LS) – mean reductions in triglyceride levels (primary end point) of –57% (95% CI: –71.9% to –42.1%; p < 0.001) and apoC3 of –77% (95% CI: –89.1% to –65.8%; p < 0.001) at week 24 with the 50 mg dose. Achieving a triglyceride level < 500 mg/dl (< 5.7 mmol/l) occurred in 90.6% of plozasiran treated participants. Plozasiran therapy increased both LDL-C and HDL-C. Plozasiran reduced remnant lipoprotein cholesterol, non-HDL-C, and apoB48, and was neutral on lipoprotein(a) levels. Plozasiran did not increase apoB. Impact on pancreatitis risk could have not been assessed as there were only 3 cases across treatment groups. Based on MRI imaging, there was a modest 2.3% increase in hepatic fat with the 50 mg dose of plozasiran [117]. The FDA approved plozasiran on November 18, 2025, as an adjunct to diet to reduce TG in adults with FCS. This approval marks plozasiran as the second disease-targeted therapy for FCS and the first siRNA medicine for this indication. The drug received prior designations including Breakthrough Therapy, Orphan Drug, and Fast Track. Plozasiran lacks marketing authorization from the EMA. It holds Orphan Medicinal Product Designation of EMA for FCS treatment. An application (EMEA/H/C/006579) is under evaluation, but no approval has been granted.

Angiopoietin-like protein 3 inhibitors

As shown in an analysis by the PROMIS and Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium, loss of function (LOF) mutations in the ANGPTL3 gene are etiologic for familial combined hypolipidemia, where TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C are low [118]. Persons inheriting LOF mutations in ANGPTL3 have greater lipolytic capacity by both LL and endothelial lipase and reduced risk for coronary calcium formation and ASCVD [119–122]. A number of therapies have been developed to investigate whether or not inhibition of ANGPTL3 is clinically safe and efficacious for dyslipidemia management.

Vupanorsen is an N-acetyl galactosamine–conjugated antisense oligonucleotide targeting hepatic ANGPTL3 mRNA. In TRANSLATE-TIMI-26 patients on statin therapy with a serum triglyceride of 150–500 mg/dl were randomized to ether placebo or different doses of vupanorsen [123]. Vupanorsen promoted dose-dependent reductions in TGs and ANGPTL3, elevations in serum transaminases, and increased hepatic fat deposition by up to 76%. Vupanorsen also induced reductions in non-HDL-C, LDL-C, and HDL-C, and modestly decreased apoB. It had a neutral effect on hsCRP. Because of safety concerns (mostly related to the increased hepatic fat fraction), the drug has been removed from further development (Jan. 2022).

Solbinsiran is an N-acetylgalactosamine-conjugated small interfering RNA (siRNA) that inhibits hepatic translation of ANGPTL3 mRNA [124]. A single dose of solbinsiran induced dose-dependent mean percentage reductions from baseline in ANGPTL3 up to 86 ±4%, TG up to 73 ±7%, LDL-C up to 30 ±16%, non-HDL-C up to 41 ±12%, and apoB up to 30 ±11% (p < 0.0001 for all). At higher doses, nuclear magnetic resonance showed significant reductions in the total number of TG-enriched lipoproteins (69.5 ±7.3%; p < 0.001)) and LDL particles (30.5 ±10.5%, p < 0.002) with solbinsiran treatment dosed at 480 and 960 mg, respectively. Adverse events occurred with similar incidence between treatment groups. Changes in hepatic fat were not measured. Clearly, given the favorable size effects on lipid parameters in this study, further investigation with this drug warranted [124].

Zodasiran is also a siRNA that inhibits hepatic translation of ANGPTL3 mRNA [125]. In the ARCHES-2 trial, zodasiran therapy given for 6 months induced dose-dependent reductions in ANGPTL3 and TG (–74% and –63%, respectively at the highest dose). The investigators also found that non-HDL-C, LDL-C, and apoB were reduced by up to 36%, 20%, and 22%, respectively. In the next GATEWAY trial, zodasiran (administered at the dose of 200 mg or 300 mg on day 1 and month 3) induced reductions in LDL-C in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HoFH) by approximately 40% with no safety signal apparent. A dose-dependent TG reductions alongside LDL-C, ApoB, non-HDL-C were also observed [126]. This approach also has a potential for managing both mixed hyperlipidemia and HoFH [127]. The ongoing phase 3 YOSEMITE trial (NCT07037771) is evaluating quarterly doses of 200 mg zodasiran versus placebo over 12 months, with change in LDL-C as the primary endpoint [128].

Gene editing with CRISPR

CTX310 is a revolutionary approach to the inhibition of ANGPTL3. CTX310 takes advantage of CRISPR-Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-caspase9) gene editing [129]. CRISPR-Cas systems are used by bacteria to silence the nucleic acids of invading viruses and bacteriophages [129]. The CRISPR-Cas9 system can also be used clinically as a type of gene modifying pair of scissors, either modifying a gene or inactivating both of its alleles. The Cas9 components of the CRISPR complex functions as an endonuclease and introduces breaks in double stranded DNA [130]. CTX310 is a liver specific, lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated CRISPR-Cas9 vehicle comprised of a mRNA and a guide RNA inducing loss of function mutations in ANGPTL3. In a phase 1 trial, a single infusion of CTX310 was shown to be safe over 1 year and it induced significant reductions in ANGPTL3 (–73.2%), LDL-C (–48.9%), TG (–55%), apoB (–33.4) and non-HDL-C (–49.8%) at the 0.8 mg/kg dose [131]. CTX310 offers the possibility of a single treatment for life-long reductions in atherogenic lipids and lipoproteins. CTX310 has entered into phase 2 trials, to begin in 2026, expanding to broader populations with longer-term outcomes.

Angiopoietin-like protein 4 Inhibitor

MAR001 is a first-in-class monoclonal antibody directed against ANGPTL4. In a dosing safety study that included 55 patients, MAR001 therapy was safe and placebo adjusted percent change from baseline to week 12 in TG and remnant lipoprotein cholesterol were –52.7% and –52.5%, respectively at the 450 mg dose [132]. TYDAL-TIMI78 is a phase 2b randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of MAR001 in patients with elevated TG and remnant cholesterol and will compare doses of MAR 001 at 300, 450 and 900 mg monthly (https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT07028749). The primary endpoint will include percent change in fasting triglyceride and remnant cholesterol, while the secondary endpoint will include percent change in VLDL and non-HDL-C. The trial is not yet completed (the estimated study completion is December 2026).

Fibroblast growth factor 21 agonist

Pegozafermin is a long-acting glycopegylated analog of human fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and was developed for the treatment of SHTG and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [133, 134]. Glycopegylation is a process by which polyethylene glycol units are added to a protein to adjust its biophysical parameters such as immunogenicity, solubility, stability, and tissue half-life [135]. FGF21 regulates triglyceride and lipoprotein metabolism by numerous routes – inhibits fatty acid biosynthesis, promotes FFA clearance from serum, increases remnant lipoprotein clearance by upregulating the LDLR, decreases VLDL biosynthesis and secretion, and improves insulin sensitivity by upregulating adiponectin. Relieving insulin resistance is known to relieve some of the inhibition of LL activity by increasing the ratio of apoC2/apoC3 [136].

The capacity of pegozafermin to favorably impact serum lipid and lipoprotein levels was tested in the ENTRIGUE trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of different doses of pegozafermin (9, 18, 27 mg subcutaneously once a week or 36 mg Q2W) in 85 patients with severe HTG (≥ 500 mg/dl [5.7 mmol/l] and ≤ 2,000 mg/dl [22.6 mmol/l]) [137]. Pegozafermin therapy induced the following placebo adjusted changes in a pooled analysis: (1) median TG were reduced (pooled) –43.7% (95% CI: –57.1%, –30.3%; p < 0.001), (2) non-HDL-C was reduced –17.9% (95% CI: –30.7%, –5.1%; p = 0.007), (3) apoB was reduced –11.8% (95% CI: –21.5%, –2.0%; p = 0.019), (4) apoC3 decreased by –32.0% (95% CI: –44.7%, –18.0%; p < 0.001), (5) HDL-C increased 34.8% (95% CI: 14.5–55.1%; p = 0.001). The largest TG reductions were observed for those 27 mg QW (–62%, placebo corrected –67%, compared to baseline values). A total of 79.7% of patients treated with pegozafermin achieved a target TG level of < 500 mg/dl, compared with 29.4% of patients on placebo (p < 0.001), 60.9% had reductions of ≥ 50% from baseline, compared with 5.9% of patients on placebo (p < 0.001), while at the highest QW dose (27 mg), 75.0% of patients had a TG reduction of ≥ 50% from baseline (p < 0.001) and 31.3% were able to achieve the TG target < 150 mg/dl compared with 0% of patients on placebo. The 27 mg weekly dose of pegozafermin produced a 73% reduction in ApoB48, consistent with a substantial augmentation of chylomicron and chylomicron remnant clearance [137]. Of great interest, based on MRI imaging, pegozafermin reduced intrahepatic fat by a placebo-adjusted 33.9% after only 8 weeks of therapy. Pegozafermin trials continue and the drug is still investigational. The ongoing trials include a study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pegozafermin in participants with compensated cirrhosis due to MASH (NCT06419374; ENLIGHTEN-Cirrhosis) and a study evaluating the efficacy and safety of pegozafermin in participants with MASH and fibrosis (NCT06318169; ENLIGHTEN-Fibrosis).

General recommendations

In the setting of FCS, volanesorsen (in Europe), olezarsen or plozasiran (in US) should now be first line therapy in addition to dietary intervention. FCS should be characterized by genetic testing for canonical, defining gene variants and clinical history. It should be differentiated from MCS and severe HTG, as these drugs do not yet have indications for these diagnoses.

Among patients with MCS or severe HTG, it is important to evaluate for insulin resistance and diabetes, as well as drugs that might be causing changes in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Insulin resistance, diabetes, and thyroid dysfunction are relatively common contributing factors to HTG. Lifestyle modification, weight loss, and dietary modification will help to reduce insulin resistance. Patients should be screened for thyroid dysfunction and managed per findings.

Icosapent ethyl (with limited availability/reimbursement in Europe – in 10/27 EU countries) has indications for treating: (a) severe HTG (TG > 500 mg/dl) and (b) HTG (TG > than 150 but < 500 mg/dl) in patients with established ASCVD or diabetic patients with 2 or more other risk factors for ASCVD. It is an effective TG-reducing agent and remains the only lipid modifying drug to date that reduces cardiovascular mortality over and above statin therapy. Benefit is independent of baseline TG levels. Given the lack of cardiovascular outcomes efficacy in available randomized clinical trials, combination therapy of EPA/DHA cannot be recommended at this indication.

Fenofibrate is indicated to reduce serum TG and raise HDL-C. It can be used in the setting of MCS and severe HTG and is safe to use in combination with icosapent ethyl. It is safe to use fenofibrate in combination with a statin. Fenofibrate showed his efficacy in patients with diabetes to prevent micro- and macrovascular complications (retinopathy, nephropathy and peripheral artery disease).

The ANGPTL3/ANGPTL4 inhibitors and pegozafermin remain investigational, but results are promising.

Practical recommendations

The issue of HTG – and especially severe HTG as a residual cardiovascular risk factor and a cause of acute pancreatitis – is complex [138]. This complexity stems not only from difficult diagnosis (most patients have secondary HTG) and some inconsistencies in study interpretations that lead to differences between guidelines, but also – and foremost – from limited availability and reimbursement of drugs targeting HTG. One cannot also fail to mention that the number of patients diagnosed with FCS/MCS (partly because of lack of knowledge on this diseases and complex genetic testing) is extremely small (up to 5000/2 million worldwide [139]); consequently, physicians in most countries, including those in the CEE region, lack sufficient experience managing these patients [140]. Accordingly, below we present the new Polish Lipid Association (PoLA) guidelines (2026), released during the XV Anniversary Congress of PoLA, as an example of practical recommendations for achieving target TG levels in high-risk patients from a Polish and European perspective [141], while awaiting the availability of highly effective drugs for HTG and severe HTG therapy (Table I, Figure 4).

Table I

PoLA 2026 Recommendations for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia

| Recommendations | Class | Level |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment with statins, or a statin combined with ezetimibe, is recommended as first line therapy to reduce cardiovascular risk in high risk individuals with hypertriglyceridemia (TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/l/≥ 150 mg/dl). | I | B |

| In patients at least at high cardiovascular risk with TG ≥ 1.5 mmol/l (≥ 135 mg/dl) despite statin therapy (or statin plus ezetimibe), consider adding icosapent ethyl1,2 (2 × 2 g/day) to reduce cardiovascular risk. | IIa | B |

| In patients at least at high cardiovascular risk with TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/l (≥ 150 mg/dl) despite statin therapy (or statin plus ezetimibe), omega 3 fatty acids2 (PUFA at 2–4 g/day) may be considered to reduce triglyceride levels. | IIb | C |

| In primary prevention patients who have achieved LDL-C target but have persistent TG > 2.3 mmol/l (> 200 mg/dl), fenofibrate in combination with a statin may be considered. | IIb | B |

| In diabetic patients at least at high cardiovascular risk who have achieved LDL-C target but have persistent TG > 2.3 mmol/l (> 200 mg/dl), consider fenofibrate in combination with a statin to reduce the risk of micro and macrovascular complications3. | IIa | B |

| In patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia (> 750 mg/dl, > 8.5 mmol/l) due to familial chylomicronemia syndrome volanesorsen (300 mg subcutaneously once weekly4) should be considered to reduce triglyceride levels and lower the risk of acute pancreatitis. | IIa | B |