Introduction

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have become the standard of care in long-term anticoagulation [1]. The primary indication is to lower the risk of systemic embolism or stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF). Oral anticoagulation use has demonstrated long-term benefits in significantly reducing all-cause and stroke mortality [2]. Patients with AF experience a fivefold increase in the risk of thromboembolic stroke, which is associated with longer admission time, and higher morbidity and mortality compared to other types of strokes. Moreover, approximately 25% of elderly patients develop AF-related stroke [3, 4]. It is estimated that, by 2060, around 19.9 million people will be diagnosed with AF [5]. This trend is the result of increased life expectancy, with associated higher burden of lifestyle risk factors and comorbidities, better survival rates after major cardiovascular events and improved screening of the high-risk population [6]. The prevalence of risk factors varies across geographical areas in Europe, leading to disparities in incidence and AF-associated mortality [7, 8]. Alcohol intake, sedentary lifestyle and dyslipidaemia are more common in Western European countries, whereas in eastern European countries, diabetes mellitus and hypertension have higher rates. However, in developed countries, AF-related mortality seems to be higher. Prevention or treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) represents another indication of DOAC use in clinical practice. VTE is estimated to affect 1–2 individuals/1000 person-years in Europe and the United States [9]. In Europe, based on a total population of 310.4 million people, the estimated annual incidence is approximately 296,000 cases of pulmonary embolism (PE) and 466,000 cases of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) [10]. VTE increases the risk of death, being associated with a threefold increased risk of all-cause mortality in patients with acute medical illness. The RIETE registry showed a 30-day mortality rate of 5.1% in patients with PE and 3.3% in patients with DVT [11]. Hence, DOACs play a pivotal role in these two major conditions with rapidly evolving incidence and a major healthcare impact. There are two main DOAC classes, direct thrombin inhibitors and direct factor Xa inhibitors. Since approval, they have proved to be superior or non-inferior to vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), causing a paradigm shift in anticoagulant prescribing and guidelines due to multiple advantages. They require less frequent monitoring and follow-up, as well as having faster onset and offset action and decreased drug and food interaction. In consequence, DOAC prescriptions have surpassed those of VKAs. In 2017, out of 7,502 patients who started an oral anticoagulant, 78.9% were on DOACs [12].

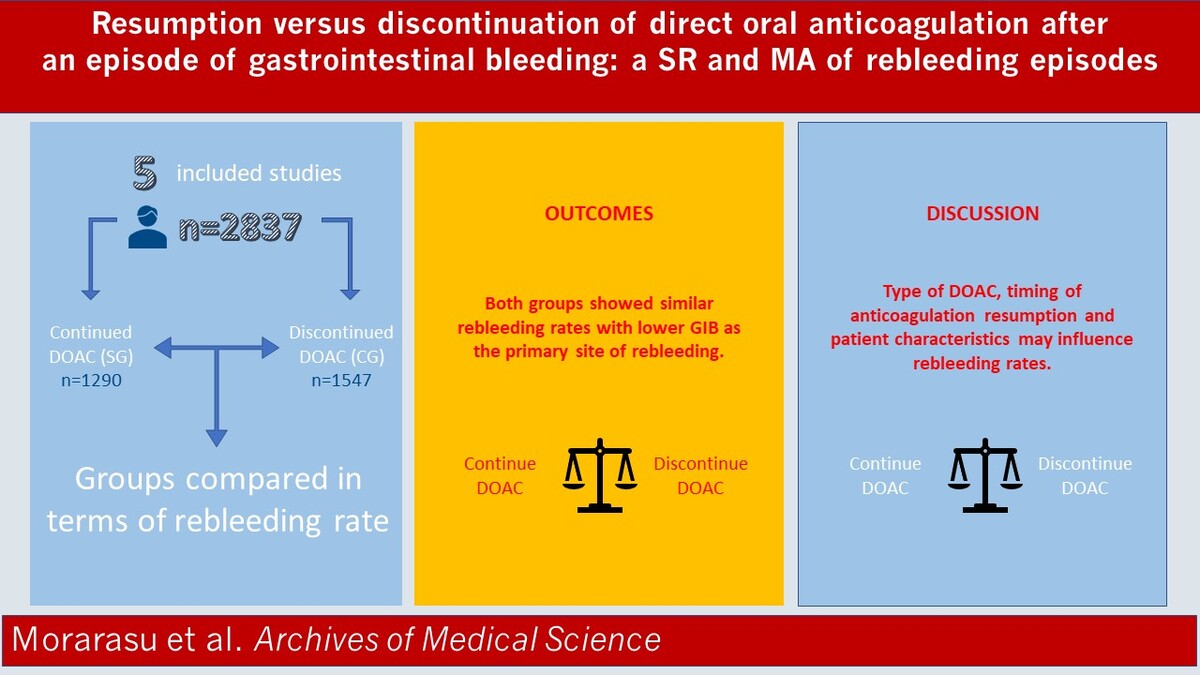

Despite their benefits, DOACs have an associated risk of bleeding. Critical bleeding sites include intracranial and gastrointestinal locations, which may occur in up to 6.62 DOAC users per treatment-years [13]. Compared to VKAs, DOACs have a reduced risk of intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) [14], but several studies have found an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB). Risk of major GIB is between 0.35% and 2.09%, while that of ICH is between 0.09% and 0.51% [1, 12, 14]. There is, however, some variation among studies. Firstly, the severity of bleeding should be clearly established by using the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) definition. Fatal bleeding arises in a critical area or organ (e.g. intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular), or requires transfusion of 2 or more units of red blood cells or a decrease of 2 g/dl in haemoglobin or causes hemodynamic instability [15, 16]. The incidence of major bleeding seems to be elevated in patients with risk factors for bleeding, at 1.1% to 4%. Life-threatening bleeding is slightly lower in incidence, estimated at 0.1% to 1% per year [13]. Secondly, the drug and the dose are additional factors. The ROCKET [17], ENGAGE-AF-TIMI [18] and RE-LY [19] trials showed a higher risk of GIB for rivaroxaban, edoxaban and dabigatran 150 mg and equal risk of GIB in the ARISTOTLE trial for apixaban when compared to VKAs [20]. Thirdly, there is little evidence regarding management of DOACs after an episode of bleeding. Extensive evidence showed benefits for using reversal agents, but subsequent anticoagulant use is a matter of debate. Previous data based on warfarin treated cohorts showed significant reduction of all-cause mortality and thromboembolism if warfarin is restarted after a major GIB. This approach may however increase the risk of rebleeding, and some experts advise reinitiating the drug around 14 days after resolution of GIB [18–24]. Although increasingly used in clinical practice, there is less evidence for management of DOACs after an episode of GIB. Previous studies have included mixed cohorts, on DOACs and warfarin or other antithrombotic drugs. Our meta-analysis and systematic review provide an updated perspective on the rate of rebleeding while on DOACs.

Material and methods

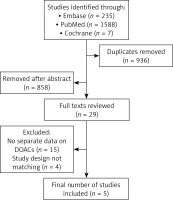

Literature search and study selection

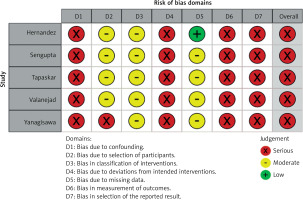

The study was registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews). The study ID is CRD42023466346. A systematic search of PubMed and EMBASE databases was performed for all comparative studies examining outcomes in patients who withheld versus resumed DOACs after a baseline episode of GIB. The following search algorithm was used: gastrointestinal AND (bleeding OR haemorrhage) AND (oral anticoagulation OR oral anticoagulant). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used as a search protocol, and the PRISMA checklist was followed to conduct the methodology [25] (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria were used according to the Problem, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) formula. The latest search was performed on 1st August 2023. Two authors (BCM and SM) assessed the titles and abstracts of studies found in the search, and the full texts of potentially eligible trials were reviewed. Disagreements were resolved by consensus-based discussion. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (Table I) and the ROBINS-I tool (Figure 2) were used to quantify the quality of eligible studies. The references of full texts reviewed were further screened for additional eligible studies. The corresponding author was contacted to clarify data extraction if additional information was necessary.

Table I

Characteristics of included studies

Eligibility criteria

Studies written in English including comparative clinical data between patients who withheld versus patients who continued DOAC after index GIB were assessed for eligibility. The main endpoints were rate of rebleeding, thrombosis and mortality. Studies including patients on warfarin or antiplatelets were excluded. Studies without comparative data were not included. Studies in which DOAC was not the only anticoagulant used were excluded. Case reports, case series, conference papers, reviews, editorials, letters to the editor and single group cohort studies were excluded. Studies written in other languages were excluded.

Data extraction and outcomes

For each eligible study, the following data were recorded: author’s names, journal, year of publication, study type, total number of patients and number of patients included in each group, mean age, gender, type of DOAC used, source of initial bleeding, and rebleeding episode (Table I).

Statistical analysis

Random-effects models were used to measure all pooled outcomes as described by Der Simonian and Laird [26], and the odds ratio (OR) was estimated with its variance and 95% confidence interval (CI). The random effects analysis weighed the natural logarithm of each study’s OR by the inverse of its variance plus an estimate of the between-study variance in the presence of between-study heterogeneity. As described previously [27], heterogeneity between ORs for the same outcome between different studies was assessed using the I2 inconsistency test and χ2-based Cochran’s Q statistic test [28], in which p < 0.05 is taken to indicate the presence of significant heterogeneity. For the main outcomes, publication bias was addressed using the trim and fill method. Computations were carried out using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 4.

Results

Eligible studies

Five studies [29–33] containing data comparing clinical outcomes between patients who withheld or resumed DOACs after GI bleeding were included (Table I). The initial search found 1823 studies. After excluding duplicates and unrelated studies based on abstract triage, 29 full texts were assessed for eligibility, out of which five matched the inclusion criteria and were systematically reviewed (Figure 1). The year of publication of included studies ranged from 2017 to 2021. All studies were retrospective with a case control design. The total number of patients included was 2837, split into two groups: the study group (SG, n = 1290) and the control group (CG, n = 1547). In the study group, patients were restarted on a DOAC after their GIB episode has resolved. In the control group, anticoagulation was stopped after the index GIB episode. Patients in the CG did not receive an alternative anticoagulant/antiplatelet treatment. Baseline characteristics were provided in 2 (Sengupta et al. and Valanejad et al.) out of the 5 studies included. Patients in the CG had similar associated comorbidities as the SG, with coronary artery disease and diabetes mellitus being the most frequent ones. More patients in the CG required blood transfusion and ICU admission. Lower GIB was the most frequent site of bleeding. Rivaroxaban was the main DOAC used in most cohorts, followed by dabigatran (Table I). The mean age in the SG was 77.2 vs 77.9 in the CG. Mean follow-up period ranged from 3 to 13.2 months (Table II).

Table II

Type of DOAC used in the study group after index GIB. Characteristics of main end points

Rebleeding rate

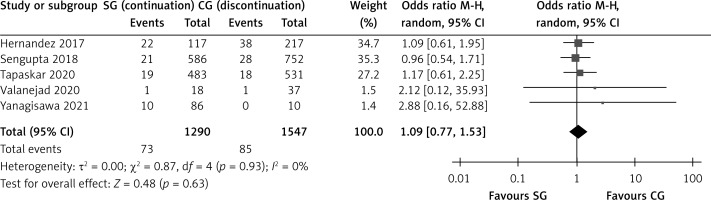

Five studies describing 2837 patients included data on rebleeding episodes. Both groups showed similar rebleeding rates, with a mean effect size of 1.087, 95% CI: 0.772–1.531, p = 0.632, Q = 0.865, I2 = 0%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Meta-analysis of rebleeding events. Favours A, fewer events in the study group; Favours B, fewer events in the control group. Each study is shown by the point estimate of the odds ratio/mean difference (OR; square proportional to the weight of each study) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the OR (extending lines); the combined ORs/mean difference and 95% CIs by random effects calculations are indicated by diamonds

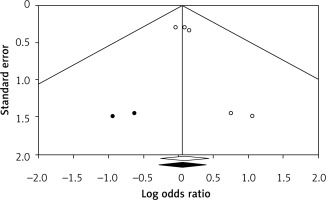

Egger’s regression intercept showed significant publication bias (p = 0.02). Publication bias was addressed via the trim and fill method in a fixed effect model, from which 2 missing studies were imputed. Using trim and fill, the imputed point estimate is 1.061 (0.757–1.487), without changing the overall significance of the results (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Trim and fill method to address publication bias by imputing two small studies. The funnel plot displays a measure of study size (usually standard error or precision) on the vertical axis as a function of effect size on the horizontal axis. Large studies appear toward the top of the graph and tend to cluster near the mean effect size. Smaller studies appear toward the bottom of the graph. Through the trim and fill method, two studies were imputed to adjust for publication bias (full black circles). On the bottom of the graph, the empty diamond shows the OR and confidence interval for the original studies, while the full diamond shows the OR and confidence interval for the original and imputed studies

Discussion

Given the variability among prospective trials and meta-analyses concerning DOACs associated GIB, we performed an updated meta-analysis and systematic review of DOAC management after an episode of index GIB. Resumption versus discontinuation of oral anticoagulation results in similar rates of GI rebleeding among the population studied.

The cohorts in our meta-analysis include patients on oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation (AF). Only one study included a mixed population, with the indication of anticoagulation for both AF and venous thromboembolism (VTE). Comparative studies evaluating the incidence of GIB in patients taking DOACs versus VKAs showed no difference in major GIB risk, for both upper major (adjusted HR = 0.94; 95% CI: 0.76–1.11) and lower (adjusted HR = 1.25; 95% CI: 0.97–1.53) GIB [34]. Risk factors associated with GIB seem to be advanced age (≥ 75 years), concomitant therapy with antiplatelets or NSAIDs, reduced body weight or renal impairment [35, 36]. Mean age in our cohort is 77.2 years, which confirms increased risk of GIB in this age group. In two of our studies (Yanagisawa and Sengupta [30, 33]), associated treatment with antiplatelets provided an increased risk of index GIB, while congestive heart failure, left ventricular assist device and end stage renal disease were noted in the study by Tapaskar [31].

Despite this information, management of DOAC therapy after GIB remains controversial. While resumption of anticoagulation reduces thromboembolic risk and all-cause mortality, it may also increase the risk of recurrent GIB. Previous meta-analyses included either a VKA predominant population, or a mixed population of VKAs and DOACs plus/minus antiplatelets, which led to increased baseline heterogeneity. Furthermore, these results cannot be extrapolated to the DOAC population, as VKAs have a different pharmacologic profile and particular indications, such as a mechanical valve [24, 37]. Our study focused on DOAC-treated patients with 1290 individuals with different DOAC agents, predominantly with rivaroxaban and dabigatran. Although the two groups showed similar rebleeding rates, there were fewer events in the control group. When considering the absolute numbers, it seems that there is a higher risk of rebleeding events in patients with DOAC resumption after the index GIB. There are several factors involved. Firstly, 48% of the study population was treated with rivaroxaban at their index GIB and approximately 42% of those with a rebleeding episode. It seems that rivaroxaban is associated with an increased risk of GI rebleeding in comparison with the other DOACs. Previous large-scale studies and meta-analysis showed similar, less favourable gastrointestinal safety [38, 39], especially at a dose of 20 mg. The other DOACs, dabigatran, edoxaban and apixaban, do not significantly increase the risk of recurrent GIB; on the contrary, apixaban showed a reduced risk of recurrent GIB [35, 40]. It is worth mentioning, however, that in patients with previous GIB, dabigatran should be used at a dose of 110 mg twice daily [41]. Hence, the general recommendation is to switch to another DOAC if a patient suffers an episode of GIB while on rivaroxaban. Secondly, the time of anticoagulant resumption plays a key role. Data from warfarin studies showed an increased risk of recurrent GIB if restarted within 7 days of the index GIB, but with a favourable outcome when restarted within 15 or even 30 days [23]. The European Society of Gastroenterology (ESGE) provides recommendations for anticoagulation resumption according to the type of bleeding (variceal versus non-variceal) within 7 days considering bleeding control and thrombotic risk. In the case of non-variceal upper GIB, anticoagulation can be restarted after 7 days or sooner if the bleeding source is appropriately controlled. In patients with variceal GI bleeding and high thrombotic risk, anticoagulation can be restarted within 3 days using heparin bridging, or within 7 days in patients with low thrombotic risk upon successful haemostasis [42, 43]. In our analysis, two of the included studies resumed DOAC within 7 days of the index GIB. The percentage of patients in the SG is higher (5.5%, 11.6%, respectively) than that in the CG (2.7%, 0%, respectively). This difference does not apply when analysing the same data for the studies resuming anticoagulation within 40 days, where we observe similar rebleeding rates between groups. Despite these observations, the data need to be interpreted with caution, as there is no statistically significant difference between the groups. This may be due to the high heterogeneity of included studies and lack of uniform data among the studied populations. Large cohort prospective studies should be performed in future. Similar observations were made in another meta-analysis, where resumption of anticoagulation within a week from the index GIB showed a 11% rate of rebleeding and 8–9% in the following 2 weeks [44]. Thirdly, there are several factors that may influence the decision to withhold anticoagulation [45] at index bleeding, including severity of bleeding, prior history of bleeding, need for intensive care unit admission, blood transfusion, concomitant antiplatelet drug use and endoscopy intervention. It worth noting that CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores did not impact anticoagulation resumption. Further large-scale studies are needed to assess the optimal timing of anticoagulation resumption, the appropriate dose as well as short-term and long-term outcomes.

The strength of this meta-analysis is the relatively large size of study population treated with DOAC. This removes the significant influence of VKAs on the investigated outcomes. Previous similar research included studies which focused on warfarin-based populations and/or with a significant frequency of associated antiplatelet treatment.

There are some limitations. We had to exclude many studies to decrease population heterogeneity, but this translated into a low number of studies (n = 5) with a small sample size, limiting the statistical power of our analysis. The included studies have notable differences in terms of inclusion criteria, baseline population characteristics, and description of primary and secondary endpoints. We did not have access to raw data, despite contacting the authors; hence, subgroup analysis could not be performed. Most of the data were based on insurance or prescription claims, which lack appropriate treatment follow-up, compliance, and other important data such as laboratory work-up. Another limitation is related to the retrospective nature of the studies, increasing the risk of selection and confounding bias; however, it does reflect real world clinical practice and it excludes performance bias. Publication bias was present, as smaller studies (Valanejad et al. and Yanagisawa et al.) had a larger effect size, favouring discontinuation of DOAC based on the higher rebleeding rate in the SG. This finding should be interpreted with caution given the low number of included studies. Performance of Egger’s test and trim and fill is low when fewer than ten studies are analysed. By performing trim and fill, two studies were imputed, favouring the CG, thus excluding the possibility of publication bias (i.e., studies that might have shown a smaller effect size may have not been published due to their small cohort and non-significant results).

In conclusion, we provide an updated meta-analysis evaluating DOAC resumption versus discontinuation after an episode of GIB among patients taking oral anticoagulation. The rates of gastrointestinal rebleeding were similar in both cohorts, with non-significantly fewer events in the discontinuation group. Certain risk factors such as advanced age, renal impairment, timing of anti-coagulant resumption and type of DOAC may influence rebleeding rates. Considering the overall risk/benefit ratio of anticoagulation after GIB, our findings suggest a potential benefit for oral anticoagulation continuation. Further validation in large cohort studies is needed.