Introduction

Carotid artery stenosis is a significant cause of ischemic stroke, and the higher the degree of stenosis is, the higher is the risk of stroke [1, 2]. It is an atherosclerotic disease affecting the extracranial carotid arteries [3, 4]. Carotid stenosis is treated in many ways, including lifestyle measures, medication, carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and carotid artery stenting (CAS) [5, 6]. The main aim of treating carotid stenosis is to reduce the risk of stroke and associated death [7]. CAS and CEA are now common surgical procedures for treating internal carotid artery stenosis [8]. CEA is currently considered the standard treatment for patients with severe symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. At the same time, CAS is a minimally invasive option for patients with a high surgical risk [9]. However, one of the most common complications of CAS and CEA is cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome (CHS) [10, 11]. It is a syndrome in which the blood flow exceeds the cerebral vessel’s automatic control range after its narrowing has been corrected [12]. It typically manifests as a headache on the pathological side or diffuse facial and eye pain. More severe symptoms include focal neurological dysfunction, seizures, and impaired consciousness [13–15]. The mechanism of occurrence of CHS is currently unclear. It may be related to the abnormal autonomic regulation of cerebral vessels in the region of long-term hypoperfusion after revascularization [16, 17]. The incidence of CHS in patients who underwent CEA and CAS was 1.9% and 1.1%, respectively [16]. CHS is an urgent clinical problem. Early detection of CHS risk after carotid revascularization is critical for rapid recovery and prognosis.

Currently, risk factors for CHS after carotid revascularization mainly include hypertension, diabetes, and coronary artery disease [18–27]. Due to limitations such as small sample sizes and different assessment scales, some factors remain controversial. In addition, most of the studies were retrospective studies, which could not determine the causal relationship between influencing factors and outcomes. Our systematic review aimed to identify risk factors for CHS after carotid revascularization, thereby improving the precision of identifying high-risk populations and providing a solid evidence base for clinicians to develop targeted therapeutic and preventive measures.

Material and methods

The meta-analysis was conducted according to the standards of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [28].

Search strategy

The Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CBM, CNKI, VIP, and Wanfang databases were searched for potentially eligible studies published up to April 30, 2024. To reduce the inclusion of irrelevant articles, MeSH terms and keywords such as “cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome”, carotid stenosis”, and “risk factors” were combined with the Boolean operator “AND”. At the same time, the literature cited in the study was searched to supplement the collection of relevant data.

Data extraction

Two researchers reviewed and extracted the literature and data, and the results were then cross-checked. If there were discrepancies, these were resolved through discussion and review. The steps of screening and extraction were as follows: (1) Read the title and abstract of the literature and exclude the literature that is irrelevant to this study. (2) Read the full text of the literature screened in the first step to determine whether the literature is included or excluded. (3) EXCEL extracts the main content, including first author, publication year, study region, sample size, study type, risk factors, and other critical information.

Quality assessment

Two researchers independently used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [29] to assess the risk of bias at three levels: study population selection, comparability between groups, exposure factors, or outcome measurement. The scale comprises eight items with a score of up to 9 points, where scores of 1–4 are classified as low quality, 5–6 as moderate quality, and 7–9 as high quality.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4 software. The OR value was selected as the primary statistical indicator, and the corresponding 95% CI was reported. Heterogeneity was assessed using the χ2 test (test level α = 0.1) in combination with the I2 test. If I2 < 50% or p > 0.1, heterogeneity between studies was low, and the fixed-effects model was used [30]. A random effects model was used if I2 > 50% or p ≤ 0.1. The stability of the meta-analysis results was checked by a sensitivity analysis using the surrogate effect model. The funnel plot of more than ten influential factors in the included literature was used to determine whether publication bias was present [31].

Results

Study selection and quality assessment

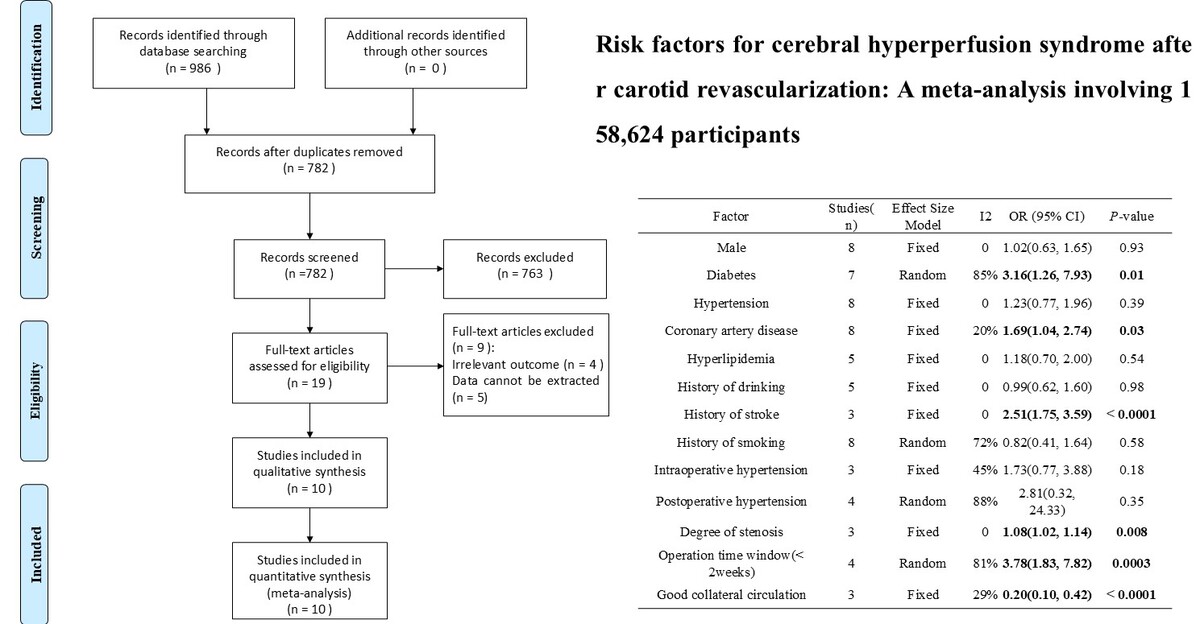

A total of 986 kinds of literature were found. After deletion, 782 items of literature were found. After reading the titles and abstracts of the literature, 19 items were selected. The full text was read according to the exclusion criteria, and ten pieces of literature [18–27] were finally included. The literature search process is illustrated in Figure 1.

The included studies were case-control studies published between 2013 and 2023, with a total sample size of 158,624. Eight studies [20–27] were from China. One study [19] was from the USA. One study [18] was from Spain. Thirteen factors related to the occurrence of CHS were considered. The NOS scores of ten pieces of literature were 7-8, all of which were of high quality. The baseline characteristics of the included literature are shown in Table I.

Table I

Overview of included studies

[i] ① Male gender, ② Diabetes, ③ Hypertension, ④ Coronary artery disease, ⑤ Hyperlipidemia, ⑥ History of drinking, ⑦ History of stroke, ⑧ History of smoking, ⑨ Intraoperative hypertension, ⑩ Postoperative hypertension, ⑪ Degree of stenosis, ⑫ Operation time window, ⑬ Collateral circulation, NOS – Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, CHS – cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome.

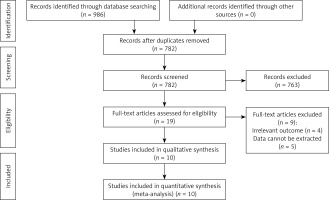

Results of meta-analysis

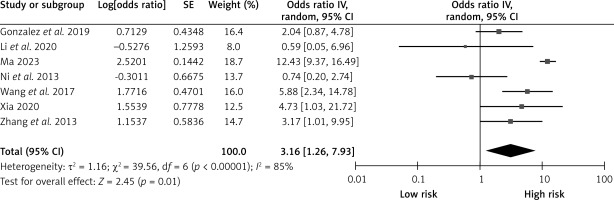

Diabetes

Seven studies reported on the effects of diabetes on CHS after carotid revascularization. The studies showed heterogeneity (p < 0.00001; I2 = 85%). The results of the random-effects model showed that diabetes was a risk factor for CHS after carotid revascularization (OR = 3.16, 95% CI (1.26, 7.93), p = 0.01; Figure 2, Table II).

Figure 2

Association between diabetes and the risk of cerebral hypoperfusion syndrome after carotid artery revascularization

Table II

Results of the meta-analysis

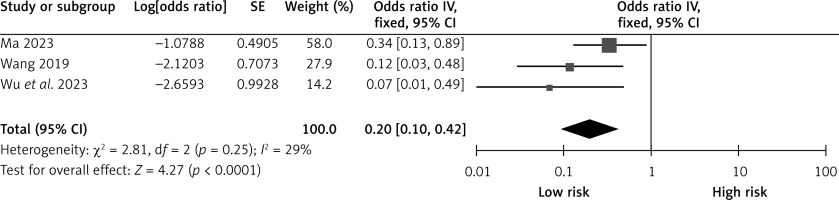

Collateral circulation

Three studies reported the effects of collateral circulation on CHS after carotid revascularization. The studies showed no heterogeneity (p = 0.25; I2 = 29%). The results of the fixed-effect model showed that good collateral circulation was a protective factor for CHS after carotid revascularization (OR = 0.20, 95% CI (0.10, 0.42), p < 0.0001; Figure 3, Table II).

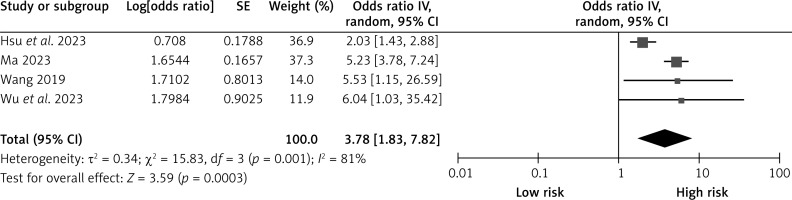

Operation time window

Four studies reported the effects of surgical time window on CHS after carotid revascularization. The studies showed heterogeneity (p = 0.001; I2 = 81%). The results of the random-effects model showed that a surgical time window of less than 2 weeks was a risk factor for CHS after carotid revascularization (OR = 3.78, 95% CI (1.83, 7.82), p = 0.0003; Figure 4, Table II).

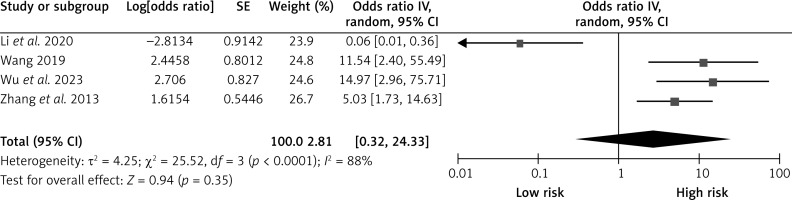

Postoperative hypertension

Four studies reported on the effects of postoperative hypertension on CHS after carotid revascularization. The studies showed heterogeneity (p < 0.0001; I2 = 88%). The results of the random-effects model showed that postoperative hypertension was not a risk factor for CHS after carotid revascularization (OR = 2.81, 95% CI (0.32, 24.33), p = 0.35; Figure 5, Table II).

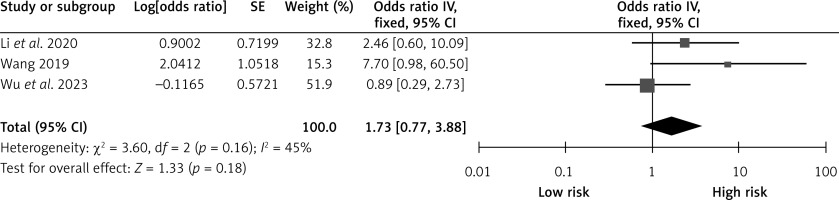

Intraoperative hypertension

Three studies reported the effects of intraoperative hypertension on CHS after carotid revascularization. The studies showed no heterogeneity (p = 0.16; I2 = 45%). The results of the fixed-effect model showed that intraoperative hypertension was not a risk factor after carotid revascularization (OR = 1.73, 95% CI (0.77, 3.88), p = 0.18; Figure 6, Table II).

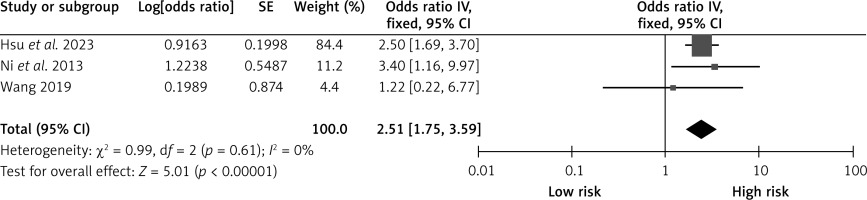

History of stroke

Three studies reported on the effects of stroke on CHS after carotid revascularization. The studies showed no heterogeneity (p = 0.61; I2 = 0%). The results of the fixed-effect model showed that stroke was a risk factor after carotid revascularization (OR = 2.51, 95% CI (1.75, 3.59), p < 0.00001; Figure 7, Table II).

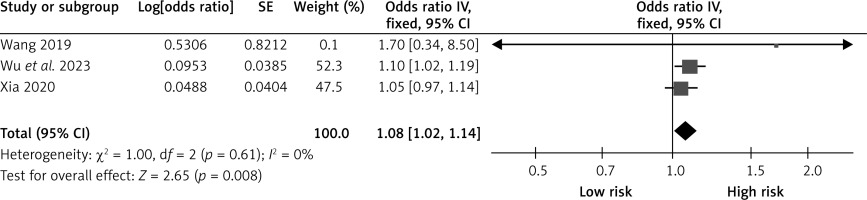

Degree of stenosis

Three studies reported the effects of the degree of stenosis on CHS after carotid revascularization. The studies showed no heterogeneity (p = 0.61; I2 = 0%). The results of the fixed-effect model showed that the degree of stenosis was a risk factor after carotid revascularization (OR = 1.08, 95% CI (1.02, 1.14), p = 0.008; Figure 8, Table II).

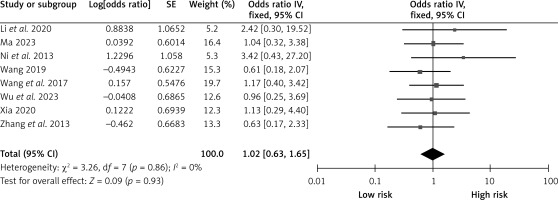

Male gender

Eight studies reported on the influence of gender on CHS after carotid revascularization. The studies showed no heterogeneity (p = 0.86; I2 = 0%). The results of the fixed-effect model showed that gender was not a risk factor after carotid revascularization (OR = 1.02, 95% CI (0.63, 1.65), p = 0.93; Figure 9, Table II).

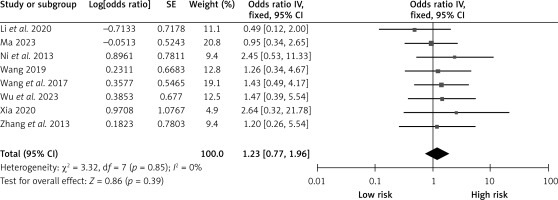

Hypertension

Eight studies reported on the effects of hypertension on CHS after carotid revascularization. There was no heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.85; I2 = 0%). The results of the fixed-effect model showed that hypertension was not a risk factor after carotid revascularization (OR = 1.23, 95% CI (0.77, 1.96), p = 0.39; Figure 10, Table II).

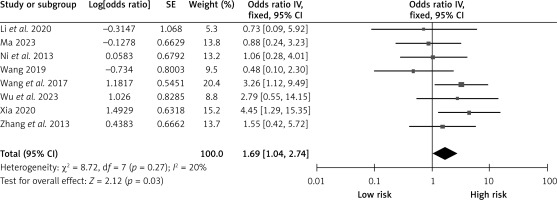

Coronary artery disease

Eight studies reported on the effects of coronary artery disease on CHS after carotid revascularization. There was no heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.27; I2 = 20%). The results of the fixed-effect model showed that coronary artery disease was a risk factor after carotid revascularization (OR = 1.69, 95% CI (1.04, 2.74), p = 0.03; Figure 11, Table II).

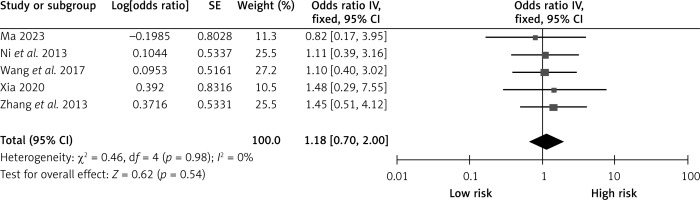

Hyperlipidemia

Five studies examined the effects of hyperlipidemia on CHS after carotid revascularization. The studies showed no heterogeneity (p = 0.98; I2 = 20%). The results of the fixed-effect model showed that hyperlipidemia was not a risk factor after carotid revascularization (OR = 1.18, 95% CI (0.70, 2.00), p = 0.54; Figure 12, Table II).

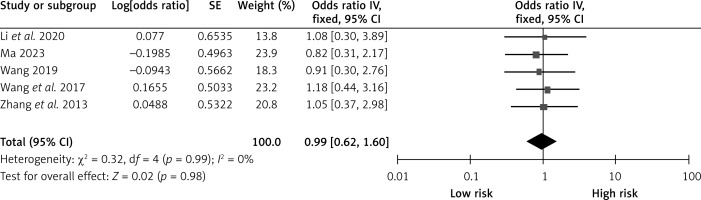

History of drinking

Five studies examined the effect of past alcohol consumption on CHS after carotid revascularization. There was no heterogeneity among the studies (p = 0.99; I2 = 20%). The results of the fixed-effect model showed that a history of alcohol consumption was not a risk factor after carotid revascularization (OR = 0.99, 95% CI (0.62, 1.60), p = 0.98; Figure 13, Table II).

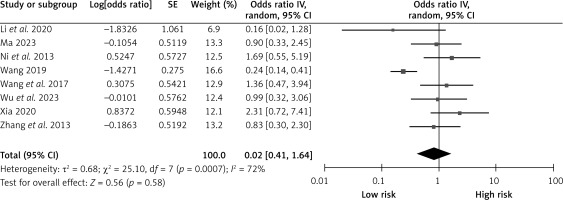

History of smoking

Eight studies reported on the effect of smoking history on CHS after carotid revascularization. The studies showed heterogeneity (p = 0.0007; I2 = 72%). The fixed-effect model results showed that a smoking history was not a risk factor after carotid revascularization (OR = 0.82, 95% CI (0.41, 1.64), p = 0.58; Figure 14, Table II).

Sensitivity analyses

The stability of the meta-analysis results was checked by a sensitivity analysis using the surrogate effect model. The meta-analysis results did not change according to the above-mentioned statistically significant risk factor change model (Table III). Therefore, the results of the meta-analysis were robust for these factors.

Table III

Sensitivity analysis of risk factors for cerebral hypoperfusion syndrome after carotid revascularization

Discussion

CHS is a severe complication after carotid artery revascularization [32, 33], and understanding the risk factors for CHS is vital for the prevention and treatment of this complication. Based on the meta-analysis results, we identified several risk and protective factors associated with CHS. The possible associations between these factors and CHS and the mechanisms that influence them are analyzed below.

Firstly, vascular disease has become an increasingly common complication in diabetics. Oxidative stress induced by hyperglycemia damages intracranial vascular endothelial cells and subsequently leads to dysfunction, such as dilation of the endothelial space and impaired clearance [34–37]. Revascularization of the carotid artery significantly increases blood flow and vascular permeability, further damaging the blood-brain barrier of intracranial vessels and leading to CHS [23, 26]. Therefore, timely intervention should be performed in patients with diabetes to reduce the occurrence of CHS. Vascular stenosis may increase the risk of local hemodynamic disturbance after revascularization, promote the risk of persistent vasospasm under high oxidative stress conditions, and increase the risk of regional brain tissue hypoxia [38]. In addition, vasoconstriction may induce abnormal coagulation function, promote the decrease of local blood oxygen saturation, and increase the risk of brain tissue hypoxia [38]. The cerebral blood vessels of patients with a history of stroke have been in a state of chronic ischemia for a long time. The cerebral blood vessels have been maximally dilated, resulting in long-term ischemia and hypoxia of the cerebral blood vessels, which may cause the partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide in the blood to affect cerebral blood flow by inducing cerebral vasodilatation in hypercapnia or vasoconstriction in hypocapnia [39]. After removing the vascular stenosis, blood flow in the affected side of the brain improved. This change caused disruptions in brain autonomic regulation, leading to CHS [24]. Research [40] indicates that severe narrowing of cerebral arteries allows for effective collateral circulation, mainly through the circle of Willis. This collateral support helps maintain cerebral blood flow in the diseased hemisphere within or near normal levels. Patients can adjust without developing CHS when stenosis is alleviated, and cerebral blood flow fluctuates significantly.

In contrast, inadequate collateral circulation results in prolonged hypoperfusion of the affected cerebral hemisphere. Once stenosis is alleviated, it cannot reroute cerebral blood flow through compensatory vessels. Consequently, cerebral vascular reactivity deteriorates, raising the risk of CHS [24]. Our meta-analysis indicates that patients undergoing surgery within 2 weeks show an elevated likelihood of CHS developing. This correlation may arise from pronounced vascular endothelial damage and inflammation after surgery, thereby raising CHS risk.

Furthermore, research suggests that surgical windows exceeding three weeks may mitigate CHS development [41]. Additionally, coronary artery disease can impair blood supply to the heart, disrupting the auto-regulation of cerebral vessels, which subsequently affects postoperative cerebral perfusion. Moreover, coronary artery disease involves physiological mechanisms such as inflammatory responses and platelet activation, potentially contributing to CHS complications. In conclusion, these determinants influence the onset and progression of CHS by modulating vascular endothelial function, neural regulation, inflammatory responses, and platelet activation. Therefore, clinical practices in carotid artery revascularization should prioritize assessing and managing these risk factors to lower CHS incidence and enhance surgical outcomes and the quality of life of patients.

The innovation of this study lies in identifying risk and protective factors for CHS after carotid revascularization. Firstly, doctors can assess the risk for CHS based on factors such as patient history of diabetes, coronary artery disease, history of stroke, stenosis, and time window of surgery and take appropriate preventive measures. Secondly, the importance of collateral circulation should also be emphasized and considered in the pre-operative assessment, which may help doctors to prevent and manage CHS and improve the prognosis of patients after surgery. Compared to other studies, the meta-analysis method in this study is more comprehensive and covers multiple potential risk and protective factors. In addition, the role of collateral circulation in protection against CHS was also discussed, and its essential role in protection against CHS was demonstrated. Thus, this study has certain advantages for clinical practice and the advancement of future research. We propose further exploration of CHS’s pathogenesis and other potential risk and protective factors for future studies.

Nevertheless, this study had limitations: (1) All studies were single-center, and there was some selection bias. (2) Most of the included studies were limited to China and may not represent the general population. (3) All included studies were case-control studies, which limited the depth of the study and led to several potential biases. (4) The limited number of studies made conducting a detailed subgroup analysis difficult. (5) Only published Chinese and English literature was considered, leading to some publication bias.

In conclusion, this study has identified CHS’s risk and protective factors after carotid artery revascularization, which is important for clinical practice. Future prospective studies with high quality, multicenter, and large sample sizes must verify and expand the relevant influencing factors for CHS after carotid revascularization. At the same time, the expert consensus method can be applied to validate this study’s results further and ensure their accuracy.

Chun Wang and Qiuhui Ran have contributed equally to this work and are co-first authors.