Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a prevalent digestive system disease that refers to the reflux of duodenal and stomach contents into the esophagus [1], causing clinical signs and symptoms such as heartburn, acid reflux, and chest pain [2]. This long-term abnormal reflux can lead to severe damage to the tissues adjacent to the esophagus, such as the mouth, pharynx, and trachea, resulting in extraesophageal symptoms such as bronchial asthma, chronic cough, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, hoarseness, and throat inflammation [3]. It may also increase the risk of esophageal stenosis, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma [4]. GERD can be caused by reduced esophageal clearance, abnormal esophageal mucosal barrier function, gastric emptying disorders, and other pathological factors such as diabetes [5].

Approximately 100 million Chinese patients have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), making China the country with the largest population of individuals with diabetes in the world [6]. Metabolic syndrome, decreased immunity, and microvascular, macrovascular, and autonomic neuropathy caused by diabetes affect gastroesophageal motility [7]. Clinically, approximately 75% of patients with diabetes have abnormal gastrointestinal peristaltic function, acid reflux, heartburn, and other GERD-related symptoms [8, 9]. This was significantly higher than in the general population. Compared with GERD alone, due to the influence of nervous system complications of diabetes, patients with diabetes and GERD exhibit weaker pain and lack obvious clinical symptoms [10]. This leads to delayed diagnosis and treatment of the disease, and eventually results in serious GERD [11].

The primary pathophysiological mechanisms linking T2DM and GERD are multifaceted. Firstly, central obesity is a common characteristic among many T2DM patients, leading to increased intra-abdominal pressure that exacerbates the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. The accumulation of visceral fat not only promotes insulin resistance but also contributes to lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction, facilitating the occurrence of gastroesophageal reflux [12]. Secondly, autonomic nervous system dysregulation can impair esophageal motility and reduce esophageal sphincter tone, resulting in decreased acid clearance and increased susceptibility to reflux [13]. Additionally, chronic hyperglycemia observed in diabetes can trigger systemic and localized inflammation, potentially worsening reflux symptoms [14]. Moreover, certain pharmacological treatments for T2DM, such as metformin, have been shown to affect esophageal motility and may lead to GERD symptoms in susceptible patients [15]. Conversely, the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), primarily aimed at controlling reflux symptoms, may have beneficial effects on glycemic control due to their potential role in improving insulin sensitivity and reducing inflammation. These bidirectional interactions highlight the complexity of managing patients with both conditions, emphasizing the need for an integrated treatment approach. In summary, the relationship between T2DM and GERD is complex, involving factors such as obesity, autonomic neuropathy, inflammation, medication effects, and alterations in gut microbiota. Understanding these intricate interactions is essential for optimizing management strategies for patients with both disorders. The exploration of PPIs as a therapeutic option presents a unique opportunity to address these interconnected diseases, potentially improving patient outcomes by alleviating GERD symptoms while also considering the broader implications for glycemic control.

The clinical treatment for patients with gastroesophageal reflux is mainly based on the inhibition of gastric acid and promotion of gastrointestinal motility [16]. Acid-suppressive drugs can reduce the secretion of gastric acid, quickly relieve the symptoms of acid reflux, and reduce further damage to the esophageal mucosa caused by reflux. Among these, PPIs are recommended as the first-line therapy for GERD [17]. However, the efficacy and safety of PPI in patients with T2DM and GERD remain unclear. This study aimed to systematically evaluate the effectiveness and safety of PPI in patients with T2DM combined with GERD to provide references for clinical use.

Material and methods

Literature retrieval strategy

The Web of Science, Cochrane Library, PubMed, Medline, and Embase databases were searched for articles available in English from their inception until December 2023. The following retrieval strategies were used: proton pump inhibitor, diabetes mellitus, type 2DM, DM, T2DM, diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastroesophageal reflux, PPI, randomized control, PPIs, GERD, rabeprazole, omeprazole. pantoprazole, dexlansoprazole, lansoprazole, ilaprazole, or esomeprazole. Reviews and references of the included articles were searched extensively.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria [18]: (1) The subjects included were type 2 diabetes patients with GERD symptoms (including acid reflux, heartburn, chest pain, dysphagia, or extraesophageal symptoms); (2) randomized controlled trials; (3) the observation group was a combination of conventional treatment for diabetes PPI, and there was no restriction on the type of PPI; the control group was conventional diabetes treatment alone or combined with placebo treatment. Routine diabetes treatment includes a low-salt and low-fat diet and blood sugar control medications.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) reviews, animal experiments, conference papers, graduation theses, and case reports; (2) duplicate documents; and (3) documents that did not provide original data or had missing data and could not be obtained by contacting the original author.

Extraction of data and assessment of its quality

The following data were extracted individually according to the designed table: the name of the paper, first author, time of publication, method of experimental design, number of subjects, age and sex of subjects, clinical effect, duration of treatment, name and dose of therapeutic drugs, and safety. The inclusion and exclusion of literature, quality evaluation, and data extraction were completed independently by two researchers. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third researcher.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using RevMan 5.4 software provided by the Cochrane Collaboration. Odds ratios (OR) were used as effect analysis statistics for dichotomous variables; in the case of continuous data, the mean difference (MD) was used. Forest plots were constructed, and heterogeneity and publication bias tests were performed. The heterogeneity test between studies was performed using the Q test and I2 value. The study results did not show heterogeneity between them when p > 0.10 and F ≤ 50%; otherwise, random effects were used. Statistical significance was determined using a p-value < 0.05.

Risk of bias and certainty of evidence

The Risk of Bias Tool 2 (RoB2) and GRADE approaches were used to assess the quality of the articles and our research. The RoB2 tool assessed five key areas: (i) the randomization process, (ii) discrepancies from the planned interventions, (iii) absence of outcome data, (iv) outcome measurement, and (v) the choice of the reported results. Disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

Results

Literature retrieval results

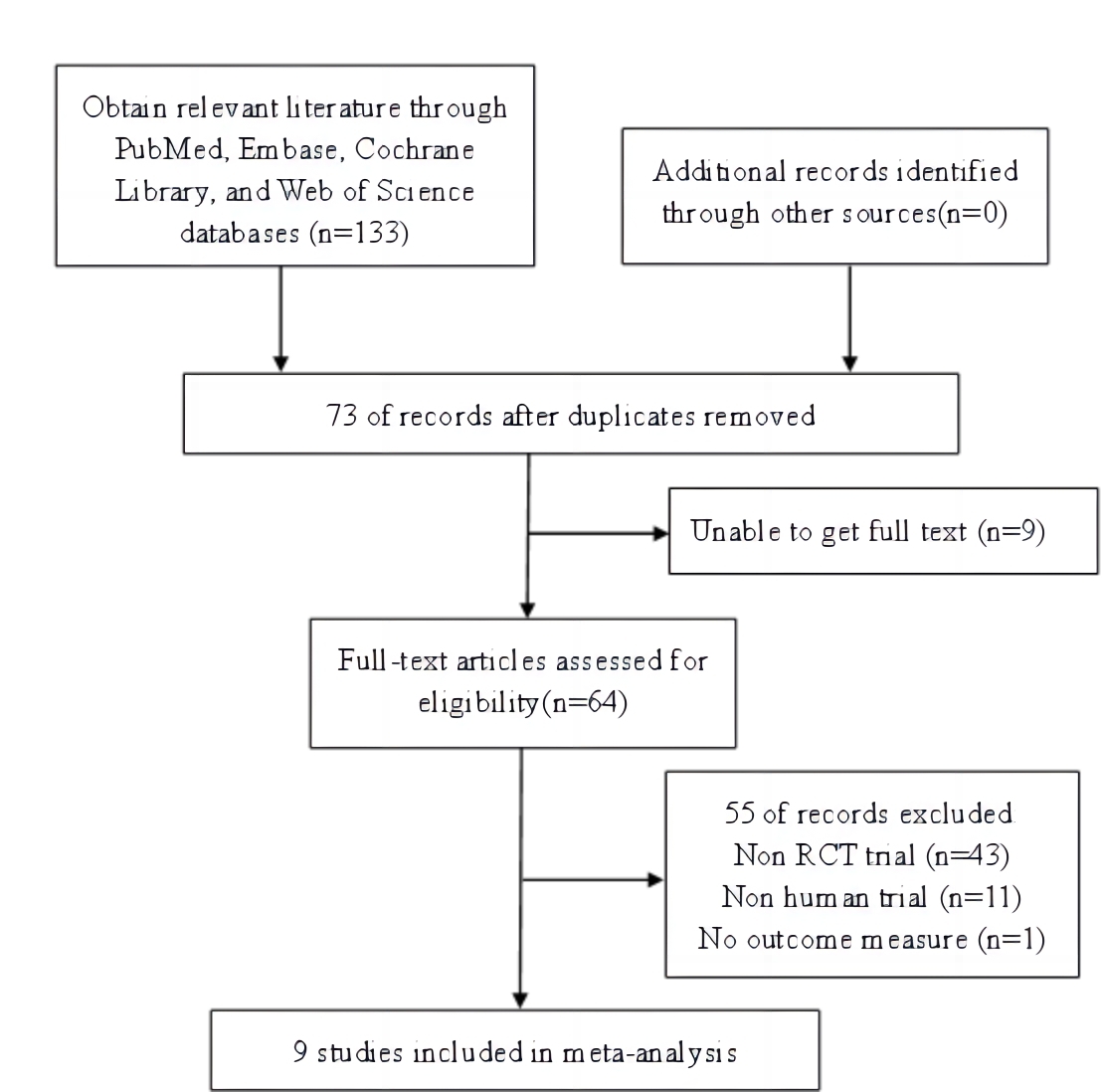

Figure 1 illustrates a flow diagram of the study. We obtained 133 articles through preliminary searches and screenings, and after review and evaluation, 73 duplicate articles were excluded. After excluding nine articles whose full text could not be obtained, 64 articles were obtained, and 55 articles whose systematic evaluations, meta-analyses, review articles, animal experiments, and results could not be extracted were further excluded. Finally, nine articles with 950 patients were included, including 445 patients in the basic diabetes treatment combined with PPI group and 505 patients in the control group with basic diabetes treatment alone.

Study characteristics

Table I shows the characteristics of the nine studies included.

Table I

Basic characteristics of 9 studies

| First author | Study design | Region | Total cases | No. of cases (PPI) | No. of cases (control) | Intervention (PPI) | Control | Treatment duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPI name | Usage and dosage | ||||||||

| Singh 2012 [27] | RCT | India | 31 | 16 | 15 | Pantoprazole | 40 mg BID | Placebo | 12 weeks |

| Hove KD 2013 [28] | RCT | Denmark | 41 | 20 | 21 | Esomeprazole | 40 mg QD | Placebo | 12 weeks |

| Takebayashi K 2014 [29] | RCT | Japan | 89 | 46 | 43 | lansoprazole | 15 mg QD | None | 12 weeks |

| González-Ortiz M 2015 [30] | RCT | Mexico | 14 | 7 | 7 | Pantoprazole | 40 mg QD | Placebo | 45 days |

| Agrawal PK 2018 [31] | RCT | India | 60 | 30 | 30 | Pantoprazole | 40 mg QD | Placebo | 24 weeks |

| Rajput MA 2020 [15] | RCT | Pakistan | 75 | 35 | 40 | Omeprazole | 20mg BID | None | 12 weeks |

| Bozkuş Y 2020 [32] | RCT | Turkey | 32 | 16 | 16 | Esomeprazole | 40 mg QD | None | 12 weeks |

| Al-Bachaji IN 2019 [33] | RCT | Iraq | 60 | 30 | 30 | Omeprazole, pantoprazole and lansoprazole | / | / | 3 months |

| Barchetta I 2015 [25] | RCT | Italy | 548 | 245 | 303 | Omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole and lansoprazole | / | / | / |

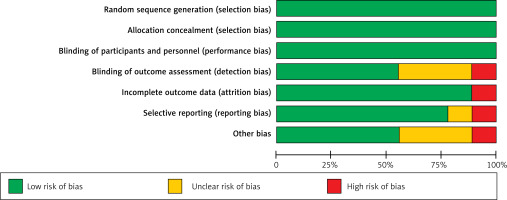

Included studies’ methodological quality

Nine studies were included in this analysis. A summary of the bias in included studies is provided in Figures 2 and 3.

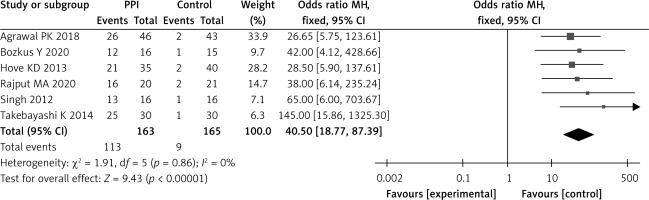

Endoscopic efficiency

Six studies analyzed the endoscopic response rate after 8 weeks of treatment. Heterogeneity test results showed that the studies were not statistically heterogeneous (p = 0.86, I2 = 0%). The meta-analysis study showed that in the PPI group, the endoscopic effective rate was 69.32% (113 cases/163 cases), while in the control group, it was 5.45% (9 cases /163 cases), OR = 40.50 (95% CI: 18.77–87.39, p < 0.001), and the two groups differed significantly (Figure 4).

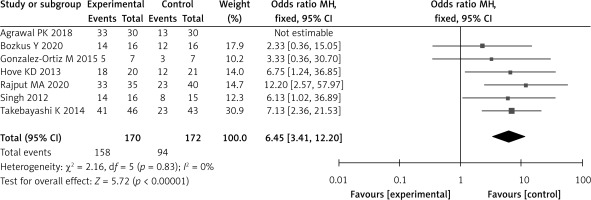

Symptom relief rates

Symptom remission rates were analyzed in seven studies. According to the heterogeneity test results, no statistical heterogeneity existed among the studies (p = 0.83, I2 = 0%). The meta-analysis showed that the symptom relief rate of patients in the PPI group was 92.94% (158 cases /170 cases), and in the control group it was 54.65% (94 cases/172 cases). OR = 6.45 (95% CI: 3.41–12.20, p < 0.001), and both groups differed significantly (Figure 5).

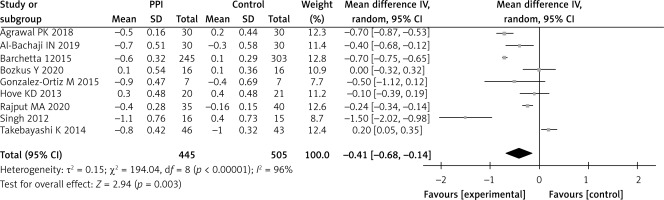

HbA1c

Changes in HbA1c levels were observed in all nine studies. Both groups showed high heterogeneity (p < 0.001, I2 = 96%). Overall, the PPI group showed an additional 0.41% reduction in HbA1c compared with the control group (WMD = –0.41; 95% CI: –0.68 to –0.14, p = 0.003) (Figure 6). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant.

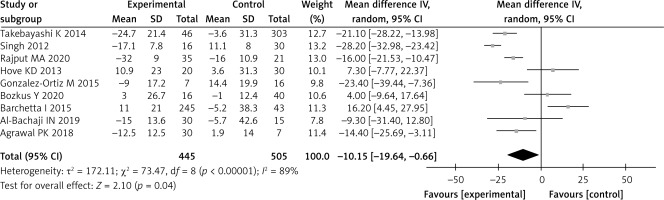

Fasting blood glucose

Changes in FBG levels were analyzed in all nine studies. Both groups showed high heterogeneity (p < 0.001; I2 = 89%). Overall, the PPI group showed an additional 10.15 mg/dl reduction in FBG compared with the control group (WMD = –10.15 mg/dl; 95% CI: -19.64–-0.66; p = 0.04), and the two groups differed significantly (Figure 7).

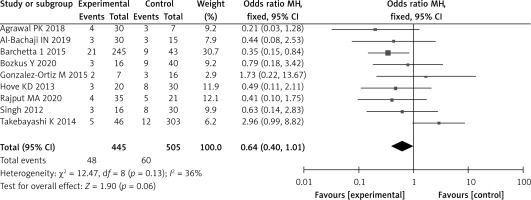

Incidence of adverse reactions

The incidence of adverse reactions was analyzed in nine studies. According to the heterogeneity test results, no statistical heterogeneity existed among the studies (I2 = 36%, p = 0.13). The meta-analysis showed that the incidence of adverse reactions in patients in the PPI group was 10.78% (48 cases/445 cases) and that in the control group was 11.88% (60 cases/505 cases). According to Figure 8, there was no statistical significance; OR = 0.64, 95% CI (0.40, 1.01), p = 0.06 (Figure 9).

Discussion

Patients with T2DM often have gastric and esophageal motor dysfunctions, and the incidence of GERD in patients with diabetes is significantly higher than that in the general population [19]. The pathogenesis of diabetes combined with GERD mainly includes the following [20, 21]: diabetic autonomic neuropathy causes primary esophageal peristaltic dysfunction, delayed esophageal emptying, and reduced esophageal clearance; gastric acid, pepsin, and bile are the direct damaging factors that cause inflammation, erosion, and ulcers of the esophageal mucosa. Proton pump inhibitors can selectively inhibit the activity of H+/K+-ATPase in gastric parietal cells, block the excretion of H+ outside the parietal cells, and reduce the secretion of H+, thereby alleviating the direct damage caused by gastric acid to the esophagus. The meta-analysis showed that the endoscopic efficacy and symptom remission rates in the PPI group after 8 weeks were 69.32% and 92.94%, respectively, which were significantly higher than 5.45% and 54.65% in the control group without PPI, p < 0.001. At the same time, the incidence of adverse reactions of patients in the PPI group was 10.78%, while that in the control group was 11.88% (not significant, p = 0.06), further indicating that PPIs are effective and safe in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic nephropathy in T2DM combined with GERD. These results are consistent with those of previous studies [22].

In addition, diabetic microangiopathy causes ischemia, neurotrophic disorders, and degeneration of smooth muscle cells, and affects the normal contraction and relaxation function of smooth muscle [23]. Chronic hyperglycemia causes dyssecretion of gastrointestinal hormones, including substance P (SP), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), motilin (MTL), gastrin (GAS), somatostatin (SS), and cholecystokinin (CCK), resulting in lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and gastrointestinal motor dysfunction [24]. The results showed that after 8 weeks of treatment, HbA1c and FBG levels in the PPI group decreased by 0.41% and 10.15 mg/dl, respectively, compared to those in the control group without the addition of PPI, and statistically significant differences were found (p < 0.05). This confirms the results of previous studies [25, 26]. The reasons may be as follows: First, PPIs are effective drugs that block stomach acid secretion, thereby reducing the stimulation and damage of gastric acid on the esophageal mucosa and improving the symptoms of GERD; by using PPI, patients are able to reduce their pain and discomfort, and may improve their diet and nutrition intake, indirectly affecting the levels of HbA1c and FBG. Second, improved insulin sensitivity and reduced insulin resistance may lower blood sugar levels with PPIs. Third, PPIs may help reduce inflammation by inhibiting gastric acid secretion, thereby improving blood sugar levels in patients.

In conclusion, the findings of this study offer significant insights that could reshape clinical approaches to managing patients with concurrent GERD and metabolic disorders. The implications for patient care are substantial, emphasizing the need for continued investigation into the therapeutic roles of PPIs beyond their traditional use in acid-related disorders. This could ultimately lead to improved overall patient outcomes and pave the way for innovative treatment paradigms in gastroenterology and endocrinology.

There are also some limitations to this study, such as clinical heterogeneity, which may have resulted from differences in patient characteristics, patient care, and treatment in different studies. Although this study controlled for bias, some residual bias may remain, which could affect the conclusions of the meta-analysis. Alternatively, to extract relevant data from various studies, different data sources and the limitations of the data extraction methods must be considered. In addition, the study only included patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, and was restricted to articles published in English, so the included literature may not be sufficiently comprehensive, which may lead to inaccurate and incomplete data. The results of this study may have been influenced by these factors. Therefore, these limitations should be considered and the findings interpreted according to the specific context. Future research should address these limitations by including larger, more homogeneous patient populations and standardized treatment protocols.

In conclusion, for patients with diabetes combined with GERD, compared with the control group, additional PPI treatment was significantly more effective and showed a greater rate of symptom remission; however, adverse effects did not increase. In addition, PPI can significantly reduce HbA1c and FBG levels in patients with diabetes mellitus and GERD, which is worthy of clinical promotion and application.