Introduction

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) represents a commonly applied surgical technique in cardiac surgery, which temporarily replaces the functions of the heart and lungs through mechanical devices to maintain the body’s blood circulation and oxygen supply, furnishing a stable surgical environment and reducing the burden on the patient’s heart and lungs [1, 2]. Notably, despite strict aseptic techniques during the CPB procedure, contact between blood and the CPB system may trigger complex immune reactions, such as complement system activation and declined levels of immunoglobulins [3, 4], elevating the risk of complications such as infections, organ dysfunction, and coagulation disorders [5–8]. Therefore, patients undergoing CPB need to stay in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) postoperatively for close monitoring and intervention of any changes in their condition [9]. One particular concern is the persistent bacterial infections following CPB surgery that can advance the development of sepsis [10–12], considerably increasing the in-hospital mortality rate of patients [13, 14].

Searching for effective preventive and treatment modalities for infectious complications in CPB is instrumental. Antibiotics, as prevalent infection control drugs in cardiac surgery, play a pivotal role in refining the survival and prognosis of infected patients as well as effectively treating severe infectious diseases such as sepsis [15–17]. Canonical antibiotic drugs include vancomycin, cephalosporins, and aminoglycosides [18]. However, the pharmacokinetic parameters of antibiotics in CPB patients are influenced by multiple factors [19], such as physiological changes induced by the connection of patients to the CPB circuit and substitution of blood loss and intraoperative bleeding [11, 20]. Therefore, there is uncertainty about whether antibiotics in CPB can also effectively refine patient prognosis and survival.

Large-scale data have been utilized in the exploration of the microbial patterns of infections in patients after prolonged CPB, with corresponding antibiotic treatment regimens formulated [5, 21]. However, there is a lack of large-scale studies to clarify the actual efficacy of antibiotics in CPB patients. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of antibiotics on the survival of ICU patients treated with CPB. Therefore, this project used Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC)-IV to evaluate factors affecting the prognosis of CPB patients and assess the survival impact of antibiotics, aiming to optimize the use of antibiotics in CPB patients, avert misuse and unnecessary use, and advance further development of clinical management and treatment protocols.

Material and methods

MIMIC-IV

The present retrospective analysis was based on the large publicly available MIMIC-IV database, which contained complete clinical data of ICU patients treated at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) between 2008 and 2019. The data covered detailed information on each patient during hospitalization, including laboratory test results and medication use (https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2/). Since the data in this database have been made publicly available and de-identified, individual informed consent was not required.

Patient selection

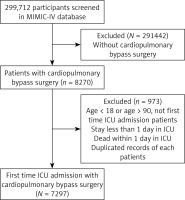

We screened 299,712 patients from the MIMIC-IV database. 8,270 patients who received CPB treatment were selected based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes (ICD-9: 39.61 and ICD-10: 5A1221Z). Subsequently, samples were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) those for whom it was not the first admission to the ICU; (2) those who had an ICU stay < 1 day or died within 1 day of ICU admission; (3) those aged < 18 or > 90 years upon admission; (4) those who had duplicate clinical records. Finally, we included clinical data from 7,297 patients who underwent CPB for the first time upon ICU admission for analysis (Figure 1).

Data collection

Clinical information of patients was collected from the MIMIC-IV database, which was categorized into six major classes: (1) demographic information, including sex, age, race, and marital status; (2) disease severity scores, including Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), and Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II); (3) comorbidity, including acute kidney injury (AKI) [22], sepsis, chronic lung disease, congestive heart failure (CHF), kidney disease, and liver disease; (4) vital signs including mean blood pressure (MBP), heart rate (HR), respiratory rate, and temperature; (5) laboratory parameters including saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2), blood glucose concentration, bicarbonate concentration, anion gap, chloride concentration, hematocrit, platelet count, hemoglobin, potassium ion concentrations, partial thromboplastin time (PTT), international normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT), sodium ion concentration, red blood cell (RBC) count, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), white blood cell (WBC) count, partial pressure of oxygen (pO2), potential of hydrogen (pH), partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), base excess, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), red cell distribution width (RDW), and creatinine levels; (6) treatment information including the use of antibiotics, use of vasopressors within 24 h of ICU admission and continued for more than 48 h (dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, vasopressin, and phenylephrine) [23], mechanical ventilation, platelet transfusion, renal replacement therapy (RRT), RBC transfusion, and antiplatelet therapy.

Main outcomes

The main outcome of samples in this project included survival time (in days: D), length of stay (LOS) in the ICU, and survival status within 30 days after ICU admission (alive, deceased).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), and differences between groups were determined by t-test. Categorical variables were presented as percentages, and differences between groups were compared with the χ2 test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Kaplan-Meier (K-M) curves were applied in the comparison of the trends of survival probability over time. Landmark analysis was employed to evaluate inter-group survival differences before and after specific time points. We used Cox regression to examine the association between antibiotic use and the risk of death in CPB patients and constructed three models based on adjusted covariates: Model 1, unadjusted; Model 2, adjusted for age, sex, and race; Model 3, adjusted for marital status, LOS, anion gap, platelets, PTT, sodium concentration, urea, WBC count, pCO2, base excess, RDW, MCV, RRT, AKI, CHF, chronic lung disease, kidney disease, liver disease, RBC transfusion, and antiplatelet therapy on the basis of Model 2. We also compared the survival differences among different subgroups of CPB patients based on sex, age, race, marital status, SOFA, mechanical ventilation, and AKI. For all analyses, bilateral p-values < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. We excluded variables with missing values exceeding 20% of the total sample size in life characteristics and biochemical indicators and handled other missing variables using the random forest (RF) method. Data analysis was performed using R (version 4.3.1) software, with R packages including mice [24] and survival [25].

Results

Baseline characteristics

The characteristics of patients undergoing CPB surgery are outlined in Table I. Two groups were classified based on survival time with a cutoff of 30 days. Among the 7,296 CPB surgery patients admitted to the ICU, 6,604 survived for more than 30 days, while 692 survived for less than 30 days. Compared to patients with a survival time greater than 30 days, those with a survival time less than 30 days were more likely to be female (37.6% vs. 28.5%, p < 0.001), older (70.01 vs. 66.72, p < 0.001), less likely to be of other or unknown races (19.4% vs. 22.7%, p = 0.037), had a longer LOS (4.69 (5.09) vs. 2.97 (4.33), p < 0.001), and were less likely to be married (51.7% vs. 61.7%, p = 0.001). In terms of vital signs, there were significant differences between the two groups in all data except for average HR (p = 0.308), MBP (p = 0.353), and lowest body temperature (p = 0.63) (p < 0.05). Laboratory indicators differed significantly between the two groups (p < 0.05). For example, patients with less than 30 days of survival had a lower average SpO2 (97.58 vs. 97.72, p = 0.014) and a higher maximum INR (1.62 vs. 1.45, p < 0.001) compared to patients with more than 30 days of survival. Similarly, the two groups exhibited significant differences in terms of comorbidity and treatment information (p < 0.05). For example, in the group not using antibiotics, CPB patients with a survival time of less than 30 days were more frequent than those with a survival time of more than 30 days (11.0% vs. 4.4%, p < 0.001). In addition, in the disease severity score of the two groups, except for GCS (p = 0.054) and SIRS (p = 0.206), other scores were also significantly different (p < 0.05).

Table I

Baseline characteristics of patients with cardiopulmonary bypass surgery stratified by 30-day survival

[i] GCS – Glasgow Coma Scale, LOS – length of stay in ICU, MBP – mean blood pressure, SAPS II – simplified acute physiology score (SAPS) II, PTT – partial thromboplastin time, INR – international normalized ratio, PT – prothrombin time, BUN – blood urea nitrogen, MCH – mean corpuscular hemoglobin, MCHC – mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, MCV – mean corpuscular volume, RDW – red cell distribution width, WBC – white blood cell, RBC – red blood cell.

As shown in Table II, among 7,296 CPB patients, 6,932 patients used antibiotics, while 364 patients did not use antibiotics. In terms of demographic information, compared to patients who did not use antibiotics, those who used antibiotics were less likely to be Black (4.0% vs. 10.7%, p < 0.001), more likely to be married (61.2% vs. 51.9%, p = 0.001), and had a longer LOS (4.53 vs. 1.71, p = 0.006). Patients of the two groups differed significantly in severity scores, vital signs, and comorbidity data (p < 0.05). Notably, the incidence of sepsis differed significantly between the two groups (p < 0.001), with 60% of patients using antibiotics developing sepsis while none of the patients not using antibiotics developed sepsis. Regarding laboratory indicators, while blood glucose (p = 0.635), highest potassium ion concentration (p = 0.089), maximum INR (p = 0.429), maximum PT (p = 0.429), lowest pO2 (p = 0.37), lowest MCH (p = 0.404), lowest MCHC (p = 0.6), and lowest MCV (p = 0.94) showed no significant differences, other indicators demonstrated significant differences (p < 0.05). Regarding treatment information, except for the use of vasopressin (p = 0.117), dopamine (p = 0.896), and antiplatelet therapy (p = 0.137), there were significant differences in other treatment information (p < 0.05).

Table II

Baseline characteristics of patients with cardiopulmonary bypass surgery according to antibiotic use

[i] GCS – Glasgow Coma Scale, LOS – length of stay in ICU, MBP – mean blood pressure, SAPS II – simplified acute physiology score (SAPS) II, PTT – partial thromboplastin time, INR – international normalized ratio, PT – prothrombin time, BUN – blood urea nitrogen, MCH – mean corpuscular hemoglobin, MCHC – mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, MCV – mean corpuscular volume, RDW – red cell distribution width, WBC – white blood cell, RBC – red blood cell.

Survival analysis

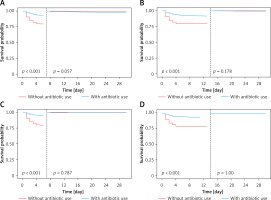

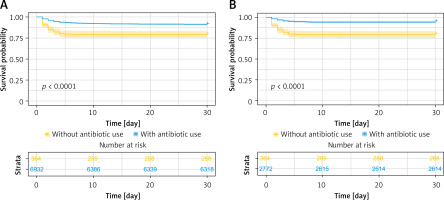

Among all patients undergoing CPB surgery, patients using antibiotics had significantly better survival than those not using antibiotics (p < 0.0001) (Figure 2 A). Specifically, the survival rates of patients not using antibiotics at 3 days, 5 days, 10 days, and 30 days were 82.1%, 79.7%, 79.4%, and 79.1%, respectively (Table III), while the corresponding survival rates of patients using antibiotics were 94.5%, 94.5%, 92.0%, and 91.1%, respectively (Table III). In further studies, we investigated the survival role of antibiotics in patients without sepsis, to determine whether prophylactic use of antibiotics was necessary for CPB patients to reduce the occurrence of severe complications. Similarly, among patients undergoing CPB surgery without sepsis, those using antibiotics had substantially higher 30-day survival rates than those not receiving antibiotics (p < 0.0001) (Figure 2 B). Landmark analysis demonstrated that the use of antibiotics considerably elevated the survival status of all CPB surgery patients (Figures 3 A, B) and CPB patients without sepsis complications (Figures 3 C, D) at 7 and 14 days (p < 0.001).

Figure 2

Survival analysis of patients with CPB based on antibiotic use. A, B – K-M 30-day survival curves for all patients (A) and non-septic patients (B), respectively

Table III

Cox model in all participants

| Cox regression model | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.383 (0.302–0.486) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 0.391 (0.308–0.497) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 0.439 (0.326–0.59) | < 0.001 |

[i] Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: adjusted for model 1 plus age, sex, race. Model 3: adjusted for model 2 plus marriage status, LOS, anion gap, platelets, PTT, sodium, BUN, WBC, pCO2, base excess, RDW, MCV, RRT, AKI, sepsis, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, renal disease, liver disease, RBC transfusion, anti-platelet.

Cox regression analysis

The results of Cox regression analysis showed that in all three models, the risk of death was significantly lower in all patients treated with antibiotics compared to those not using antibiotics (Model 1: HT = 0.383, 95% CI: 0.302–0.486, p < 0.001; Model 2: HT = 0.391, 95% CI: 0.308–0.497, p < 0.001; Model 3: HT = 0.439, 95% CI: 0.326–0.59, p < 0.001) (Table III). Based on Cox model regression analysis of CPB patients without sepsis, in three different covariate-adjusted models, patients treated with antibiotics had a significantly lower risk of death compared to those not using antibiotics (Model 1: HT = 0.247, 95% CI: 0.188–0.324, p < 0.001; Model 2: HT = 0.258, 95% CI: 0.196–0.340, p < 0.001; Model 3: HT = 0.461, 95% CI: 0.327–0.648, p < 0.001) (Table IV).

Table IV

Cox model in participants without further diagnosed sepsis

| Cox regression model | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.247 (0.188–0.324) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 0.258 (0.196–0.340) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 | 0.461 (0.327–0.648) | < 0.001 |

[i] Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: adjusted for model 1 plus age, sex, race. Model 3: adjusted for model 2 plus marriage status, LOS, anion gap, platelets, PTT, sodium, BUN, WBC, pCO2, base excess, RDW, MCV, RRT, AKI, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, renal disease, liver disease, RBC transfusion, anti-platelet.

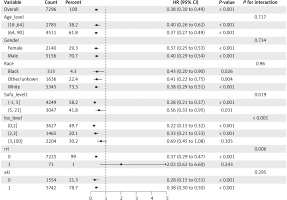

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis (Figure 4) revealed a significantly lower risk of death in subgroups of CPB patients with SOFA scores ranging from − 1 to 5 (HT = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.21–0.37, p < 0.001), ICU admission ≤ 3 days (0–2 days: HT = 0.22, 95% CI: 0.15–0.32, p < 0.001; 2–3 days: HT = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.21–0.53, p < 0.001), and no RRT (HT = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.29–0.47, p < 0.001).

Discussion

In this study, the frequency of sepsis in CPB patients receiving antibiotic treatment was 60%. After comprehensive statistical analysis, we found that antibiotic treatment considerably reduced the risk of death for all CPB patients and CPB patients without sepsis (p < 0.001). Moreover, the subgroup of CPB patients with SOFA scores ranging from –1 to 5, ICU stay ≤ 3 days and those not undergoing RRT had a significantly lower risk of death (p < 0.001). These results emphasize the critical role of antibiotics in reducing the risk of death in CPB patients.

The findings of this project indicated that antibiotic treatment has obvious benefits for the survival of patients undergoing CPB treatment. Although patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB have established conventional treatment strategies to control the initial high inflammatory response, persistent immunosuppression remains a clinical challenge, making patients susceptible to postoperative infections and increasing the mortality risk [26, 27]. Observational studies have demonstrated that infections following CPB cardiac surgery include sternal wound infections, mediastinitis, endocarditis, and device-related infections, and are closely associated with adverse outcomes and rising treatment costs [28, 29]. Early diagnosis and appropriate antibiotic use to control infections can aid in reducing mortality from postoperative complications, shortening hospital stays, and improving outcomes for cardiac surgery patients [15]. Patients with bloodstream infections following CPB are likely to be infected with Gram-negative bacilli [5, 21]. Oral antibiotics, especially those with high bioavailability, possess impactful efficacy in eradicating Gram-negative bloodstream infections [30]. Additionally, antibiotic therapy can effectively increase the survival rate and shorten the treatment time for infected patients in the ICU [31]. A retrospective study on patients progressing from sepsis to septic shock in the ICU also demonstrated that antibiotic treatment regimens containing at least two extracorporeal active antibiotics can improve survival rates [32]. Combining our results, antibiotics are instrumental in treating postoperative infections including sepsis in ICU patients undergoing CPB, greatly promoting patient survival rates.

In this study, the frequency of sepsis in CPB patients receiving antibiotic treatment was 60%. Sepsis, as a severe systemic infection complication after CPB cardiac surgery, is one of the important risk factors affecting patient prognosis [12, 33, 34]. Timely administration of antibiotics to septic patients can improve patient survival [35, 36]. Furthermore, we further dissected the survival effect of antibiotics in CPB patients without sepsis to evaluate the necessity of prophylactic antibiotic use in this population. The results revealed that antibiotics greatly reduced the mortality risk in such patients. This result may be attributed to the effective prevention and control of infections by antibiotics. For example, perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is one of the most essential measures to prevent surgical site infections in cardiac surgery, which can reduce the incidence of surgical site infections in cardiac surgery and other surgeries, thereby minimizing the occurrence rates of related complications and mortality [18, 37]. In conclusion, the rational use of antibiotics for CPB patients can help improve patient survival.

We found that the risk of death was considerably elevated for CPB patients with ICU stays exceeding 3 days. The result is in line with previous research findings, which showed that in cardiac surgery patients, those with ICU stays of more than 3 days had dramatically elevated ICU, in-hospital, and long-term mortality rates compared to those with stays of 3 days or less, mainly due to organ failure [38]. The SOFA score has been validated in cardiac surgery patients as an objective indicator for assessing the severity of organ dysfunction [39, 40]. This scoring system aims to quantitatively assess the severity of dysfunction in six organ systems – the respiratory system, circulatory system, renal system, hematological system, liver, and central nervous system – having a pivotal impact on the recuperation process following heart surgery [41]. Former studies have indicated that patients undergoing cardiac surgery may develop organ dysfunction, which can further deteriorate and affect the prognosis of patients [42]. In the population undergoing cardiac surgery, the SOFA score has demonstrated good discriminative ability in predicting in-hospital mortality [43]. A large-scale study based on the MIMIC-III database confirmed that cardiac surgery patients with higher SOFA scores (SOFA score ≥ 7) have a higher risk of adverse clinical outcomes, including higher in-hospital mortality, 28-day mortality, 90-day mortality, and 1-year mortality, as well as longer ICU stay [42]. This is in line with our study, where the mortality risk in CPB patients with SOFA scores of –1 to 5 was significantly higher than in CPB patients with scores of 5 to 21. Therefore, the present work not only underscored that a longer ICU nursing time may indicate a slow treatment response and adverse prognosis in CPB patients but also supplied further data support to reiterate the importance of organ failure in assessing prognosis for CPB patients. By timely and comprehensive assessment of the organ function status of CPB patients, clinicians can more accurately predict patients’ survival probability and propose timely treatment and management strategies. The results of this study also demonstrated that CPB patients who received RRT had an elevated risk of death. An investigation into the long-term survival rate, possibility, and timeline of kidney function recovery in cardiac surgery patients requiring postoperative RRT revealed that postoperative RRT is an independent risk factor for patient mortality [44]. In another multinational study report, the incidence of acute renal failure requiring RRT in ICU patients ranged from 5% to 6%, greatly associated with a high in-hospital mortality rate [45]. Therefore, for critically ill CPB patients who have undergone RRT, close monitoring of their kidney function recovery is necessary to adjust treatment plans promptly.

To our knowledge, this is the first project to investigate the relationship between antibiotics and survival in critically ill CPB patients, providing new insights into the postoperative management of CPB patients. Antibiotic therapy is not only beneficial for patients who have already developed an infection, but also has a significant effect on preventing postoperative infections. Based on the results of the study, we suggest that the following improvements should be considered for implementation in daily clinical practice for post-CPB patients: 1. Prophylactic antibiotic use should be considered for all post-CPB patients, even when there are no signs of infection, in order to minimize the risk of infection. 2. Enhanced monitoring of post-CPB patients should be performed to allow for early diagnosis of infection and timely initiation of antibiotic therapy. 3. Patient-specific circumstances, including the type of possible infection and the pharmacokinetic properties of the antibiotic, should be taken into account when selecting antibiotics.

Our study has certain limitations. Firstly, the exclusion of variables with missing values exceeding 20% of the total sample size in vital signs and biochemical indicators may influence the results. In addition, sample size limitations may affect the statistical significance and external validity of the results. Although we used the MIMIC-IV database for our analyses, the patient population in this database may not be fully representative of all CPB patients, especially since there may be differences in treatment practices across hospitals and regions. Second, the acquisition and quality of the data may have influenced the study results. Since this study relied on observational data, there may be information bias or omissions, especially the lack of specific dose, start time, and total number of days of antibiotic administration. These factors may have led to an underestimation or overestimation of antibiotic efficacy. Additionally, the study failed to control for all potential confounders, which may have affected patient survival and prognosis. Therefore, although the results show a significant benefit of antibiotic treatment on survival in patients with CPB, caution should be exercised in interpreting these results. Finally, because this study was conducted based on an observational database and thus lacked a randomized controlled trial design, potential bias could not be completely excluded. Therefore, prospective randomized controlled trials should be considered for future studies to verify the actual efficacy of antibiotics in CPB patients and to further explore the optimal antibiotic use strategy.