Introduction

Since its outbreak [1–3], coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has raised concern for immunosuppressed patients usually identified as vulnerable to viral infections [4, 5]. Potentially life-threatening SARS-CoV-2 infection complications, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), are suspected to be associated with the cytokine storm, causing hyperinflammation, hypercoagulability and severe hypoxemia [6, 7]. Although the lack of a hyperimmune response to SARS-CoV-2 may be protective in patients receiving pharmacological immunosuppression (IS), available studies provide conflicting results about the disease course in this group of patients [8–18].

As the pandemic continues to impact the medical management of all categories of patients and the emergence of new variants changes the clinical impact and transmissions rates [19], data regarding the outcome of COVID-19 in immunosuppressed individuals are partially controversial. First, a higher prevalence of COVID-19 has been observed in patients with autoimmune systemic diseases, who are usually treated with immunosuppressive medications [20]. Furthermore, these patients seem to be more likely to have a more serious course of disease, even if results differ between cohorts [21, 22], whereas the impact of comorbidities, known to affect COVID-19 outcomes negatively, has to be considered [23–28]. In addition, conditions frequently associated with autoimmune diseases, as vitamin D deficiency and dysbiosis, could have an impact on systemic inflammation, increasing the risk for more severe COVID-19 [29]. Finally, data regarding impaired immune responses to anti-COVID-19 vaccines in these populations cause uncertainty in their management and confirm their vulnerability [30, 31].

Among comorbidities that are considered relevant in COVID-19, it has been hypothesised that patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) may be particularly prone to severe COVID-19 because of the immune dysregulation associated with this chronic condition [32]. However, published studies provide divergent results regarding the impact of CLD on COVID-19 progression and outcome, although the presence of cirrhosis is associated with higher mortality [33–38]. Accordingly, we focused on this subpopulation of patients for additional analysis.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess outcomes of COVID-19 in patients on immunosuppression (IS) who required hospitalisation, compared to patients without IS treated in the same time period and in the same hospitals. We investigated whether IS was associated with the development of severe COVID-19, defined as longer hospitalisation, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) or death in a cohort consisting of all individuals from southern Switzerland who were admitted to our institution with confirmed COVID-19.

Material and methods

Study design and setting

We carried out a prospective observational cohort study evaluating 442 patients who were admitted to Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale, the primary health institution in southern Switzerland, with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, as determined by PCR nasopharyngeal swabs. Patients were consecutively included from February 25th to May 11th, 2020, with their demographic, clinical, laboratory and treatment information that was daily collected and analysed until death or hospital discharge. Immunosuppressed patients were identified based on whether they were under IS at the time of hospital admission or had received prescriptions for immunosuppressants for at least 4 consecutive weeks during the 6 months prior to hospitalisation. Immunosuppressive treatment included cytotoxic agents (chemotherapeutics, calcineurin inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, folate antagonists, inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase inhibitors, purine analogues, alkylating agents and Janus kinase inhibitors), interleukin inhibitors, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors, or systemic corticosteroids (with a dosage higher than or equal to 5 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent). Relevant baseline medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and CLD accounted for comorbidities. Clinical outcomes such as length of hospital stay, admission to ICU and mortality were monitored until May 11th, 2020.

Statistical analysis

Different random variables were compared between patients with and without IS with parametric (Student t-test) or non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney, χ2 test or Fisher exact test), as appropriate. To assess the potential role of pre-existing IS on different outcomes (mortality; length of hospital stay; ICU admission), univariate and multivariable regression models were used. Only random variables with a p-value < 0.1 identified in the univariate analysis were entered in the multivariable models. All tests were performed two-sided, and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 15 (StatCorp. LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Among 442 adult patients with COVID-19 included in this study, we found 35 (7.9%) patients who were on IS at the time of hospital admission or in the previous 6 months for at least 4 consecutive weeks. The median age was 70.6 (IQR: 65.9–75.4) years, and 23 (65.7%) patients were men, while 407 (92.1%) patients were not under IS at admission and did not have a recent history of IS. Immunocompromised COVID-19 patients were older than patients without IS (mean age: 70.6 vs. 68.9, p = 0.48), while both groups had higher proportions of male patients (65.7% vs. 61.7%, p = 0.22). Characteristics of patients with or without IS are detailed in Table I.

Table I

Characteristics of patients sorted by history of pharmacological immunosuppression at admission. Statistically significant differences are highlighted in bold

A significant number of patients on IS (n = 19, 54.3%) suffered from autoimmune diseases, while 4 (11.4%) were solid organ transplant recipients, 4 (11.4%) had malignancy, 4 (11.4%) had a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and 4 (11.4%) had other chronic conditions. Oral corticosteroids (n = 30, 85.7%), specifically prednisone or equivalent on a dosage higher than or equal to 5 mg/day, were the most common immunosuppressive medications. Other used immunosuppressants are detailed in Table I. Among the patients who were still under IS at hospital admission (n = 16/35, 45.7%), 4 (25%) patients underwent reduction or discontinuation of IS. The most common strategy of managing IS at admission was continuing the treatment in 12 out of 16 (75%) patients. Fourteen (40%) patients had received IS 6 months before admission and were off treatment at the time of hospitalisation. No data regarding IS management were available in 5 (14.3%) patients.

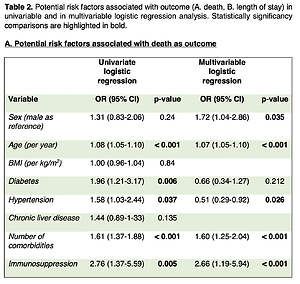

Immunosuppressed patients showed similar rates of baseline comorbidities as compared to patients who were off IS (median number of comorbidities = 2 for both groups, p = 0.06), showing a higher incidence of diabetes (n = 14/35, 40% p = 0.01), although body mass index (BMI) was lower in patients under IS (25.8 (23.9–27.7) vs. 28 (27.2–28.8), p = 0.10). Compared with patients without IS, immunosuppressed patients showed higher mortality (n = 16/35, 45.7% vs. n = 95/407, 23.3% p = 0.003) and a longer hospital stay (median = 15.5 days vs. median = 11 days, p = 0.0144), while their admission at ICU was not significantly higher (n = 11/35, 31.4% vs. n = 76/407, 18.7%, p = 0.069). Moreover, in the univariate and multivariable logistic regression (Table II), IS was associated both with mortality (OR = 2.76, p = 0.005 and 2.66, p < 0.001) and length of stay (OR = 6.14, p = 0.005 and 5.98, p = 0.007), but not with ICU admission (OR = 2.01, p = 0.08 and 1.88, p = 0.11). No gender differences were observed for mortality in the group of patients under IS (male, n = 10/23, 56.5% vs. female n = 6/12, 50% p = 0.71).

Table II

Potential risk factors associated with outcome (A – death, B – length of stay) in univariable and in multivariable logistic regression analysis. Statistically significant comparisons are highlighted in bold

A. Potential risk factors associated with death as outcome

B. Potential risk factors associated with length of stay

Treatment with immunosuppressants in patients with concomitant CLD (n = 8/35, 22.9%), primarily fatty liver (n = 6/8, 75%) and mild disease, only 1/8 being cirrhotic, was not associated with worse outcomes (Table II). The distribution of IS in this subgroup of patients was similar to the whole group under IS, most patients (6/8, 75%) were on steroids, and 1 patient each was receiving methotrexate and tacrolimus for previous liver transplantation. However, due to the limited number of patients with CLD in our cohort, no further assertions were possible.

Discussion

In the present prospective observational study, IS in patients with COVID-19 was associated with increased mortality and a more extended hospital stay. Although previous studies have provided conflicting results regarding the impact of IS on COVID-19 outcomes, our findings clearly showed that patients on IS were at significantly higher risk of severe and prolonged COVID-19. In our cohort, IS was found to be an independent risk factor for longer hospitalisation and in-hospital mortality from COVID-19.

Managing patients on IS who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 has been challenging since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Specifically, the assumption that poor antiviral immunity in immunocompromised patients entails an increased risk for COVID-19 complications, as seen for other respiratory viruses, diverged from some initial observations in chronically immunosuppressed patients, who showed no association with more severe COVID-19 or even protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection due to their reduced immune response [8].

These findings indicate that IS is a risk factor for more severe COVID-19, in line with previously reported results from other patient cohorts suggesting that immunocompromised patients have a higher risk of worse outcomes than the general population [39–44]. However, looking at overall available data in immunosuppressed patients, which remain conflicting in terms of the outcome of COVID-19 with respect to IS, those patients with the most severe disease are more likely to have several concomitant comorbidities and older age, and their outcomes do not relate only to degree of IS. This report brings new added value, first because it is based on information from a fully detailed, multicentre centralised clinical data management system, providing accurate and reliable results. Furthermore, IS was also confirmed to be independently associated with worse outcomes after univariate and multivariable logistic regression adjustments for comorbidities.

Confirmation that immunosuppressed patients are more likely to develop a severe disease is relevant to their management and suggests a need for early COVID-19 vaccination in these patient categories [31]. In addition, individualised IS adjustments and prioritisation of COVID-19 treatments for infected subjects on IS, such as monoclonal antibody therapy [45, 46], are required. Indeed, immunosuppressed patients with COVID-19 reported longer hospital stays and higher mortality than non-immunosuppressed patients. Nonetheless, patients under IS were more often admitted to the ICU due to the severe course of COVID-19, although this finding was not statistically significant.

Due to the broader proportion of patients under corticosteroids, we can assume that poor outcomes were further associated with steroid-based IS. This finding is actually broadly consistent with other published studies [16, 39, 44, 47]. Moreover, most patients in our cohort continued their immunosuppressive medications once admitted. Although the population size is too small to estimate the impact of this strategy adequately, this would suggest that there are no protective benefits of IS in the long term. However, none of the patients in our cohort, who were under IS after solid organ transplantation (4/35), underwent a reduction in IS. This resulted in no rejection episodes during this time and a good outcome, with no ICU admission or death.

In our cohort, we found no significant differences in sex, age and BMI between immunosuppressed and non-immunosuppressed patients, resulting in two homogeneous groups. Male gender was confirmed to be a predictor of higher mortality in hospitalized adults with COVID-19 (Table II A), and this finding is in line with previous studies [48]. However, further analysis did not show any gender differences for mortality in the group of patients under IS, probably because of the small number of patients in this group. Although diabetes was more frequent in patients under IS, applying univariate and multivariable logistic regression adjustments for comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, and CLD allowed us to confirm IS as independently associated with mortality and length of stay. This observation suggests that IS should always be considered as a risk factor similar to well-known risk factors that favour a more severe disease course. However, in a separate analysis of comorbidities, the presence of CLD was not associated with worse outcomes in immunosuppressed patients. Although limited information is available on the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with CLD, our finding is inconsistent with previous studies, where a higher risk for more severe disease has been described in patients with CLD when compared with patients without CLD [49]. However, individuals with CLD under IS because of underlying autoimmune hepatitis and even liver transplant recipients have shown comparable outcomes of COVID-19 with matched controls [50, 51]. Besides specific considerations regarding the known immune dysregulation in patients with CLD, the severity of COVID-19 in this populations is mostly influenced by comorbidities rather than additional factors such as IS. However, because of the very small number of patients with CLD and IS included in our analysis, no inference could be drawn.

Our study includes the following limitations: first, it is a prospective observational study, but it was initially designed to describe COVID-19 in all admitted patients. Therefore, no data were collected to specifically assess immunosuppressed patients, which may have resulted in a significant percentage of missing information. Second, we could include only a small, heterogenous group of patients under IS, which precluded related subgroup analyses (e.g., with respect to type of organ transplant and autoimmune disease, dosage and duration of IS). Furthermore, although no significant difference was found in comparison with patients not under IS, patients under IS were slightly older and more commonly reported certain comorbidities such as diabetes, which are both known risk factors for more severe COVID-19. Third, outcomes were analysed in a short-term setting, whereas more information is also needed on long-term morbidity and mortality in immunosuppressed patients. Fourth, the proportion of in-hospital deaths in patients under IS was very high in our cohort. This finding could possibly be attributed to the overloaded healthcare system during the first wave of the pandemic, which might have raised thresholds for admission to the ICU for certain categories of patients such as those of older age and/or with severe comorbidities. However, this does not fully explain the higher mortality in our immunosuppressed patients. Indeed, the proportion of patients admitted to the ICU was at least not lower among patients under IS when compared to the patients not under IS. In addition, the management of COVID-19 has changed constantly since the period in which our study was conducted, namely the first pandemic wave. Data now suggest the beneficial effect on mortality of vaccinations and COVID-19-specific therapies, including systemic corticosteroids, tocilizumab, remdesivir and anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies in the general population [52–54], as well as in immunosuppressed individuals [55]. Finally, although our analyses were adjusted, we cannot completely exclude some residual confounding due to non-measured variables, and the number of testable variables in our multivariable models is limited by the number of patients under IS.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that immunosuppressed patients hospitalised with COVID-19 experience longer hospital stays and higher in-hospital deaths than non-IS patients. Therefore, the impact of COVID-19 on this vulnerable population remains critical, and further data regarding disease severity and vaccine response are required to improve the management of these patients.