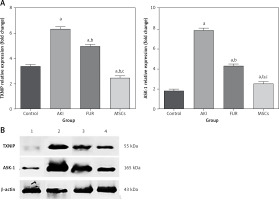

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a serious complicated disease that leads to a sudden reduction in glomerular filtration and deterioration in kidney function [1]. These disorders can disrupt metabolic, electrolyte, and fluid homeostasis over hours to several days. The regenerating capability of the mammalian kidney is low, which is a severe problem since kidney disease is currently a major worldwide health concern. Moreover, AKI is caused by a range of factors such as ischemic damage from sepsis, surgery, infections, toxic chemicals, and trauma [2].

Early diagnosis of AKI cases is difficult, which can lead to irreversible renal damage and the need for treatments such as dialysis or transplantation [3]. This limited regenerative capability of the mammalian kidney makes AKI a global public health concern, and it is associated with mortality and morbidity [4]. Despite recent understanding of the underlying pathophysiology, clinical diagnosis, and discovery of new renal biomarkers, there is currently no specific pharmaceutical treatment for AKI, and the focus has shifted to regenerative medicine as a novel therapeutic approach [5].

The pathogenetic process of AKI includes both local impacts on the whole body and the kidney [6]. Consequently, diuretics such as furosemide (FUR) are widely used in the management of hypertension in AKI patients [7]. Additionally, FUR can increase Na excretion by 20%, which reduces the amount of extracellular fluid, minimizes concomitant conditions or complications, and impairs kidney function [8]. However, the expected efficiency of treatment was still not achieved due to the toxic effects of drug therapy, the inconvenience of the dialysis process, and the high cost of donors for kidney transplantation. Therefore, new therapeutic strategies are urgently needed to suppress kidney disease progression. Recent research has focused on the discovery of new therapeutic tools to enhance the regeneration abilities of the kidney after injury caused by AKI [9].

Currently, a promising treatment strategy for many disorders is cell-based replacement therapy. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), as one of the essential members of the stem cell family, can be obtained from many tissues such as bone marrow, peripheral blood, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord. MSCs have potential biological properties of anti-inflammation, immunomodulation, and tissue repair. Clinical and preclinical studies have shown that MSCs exhibit protective and reparative effects on renal injury [10]. Additionally, MSCs possess anti-apoptotic, antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties via secretion of extracellular vesicles (EVs) [11]. Overall, MSC treatment is considered to be the most promising stem cell therapy for kidney disease treatment [12]. Previous studies have indicated that MSCs are safe and effective when used for the treatment of organ injury [13, 14]. MSCs can perform their functions by producing hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)-2, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and CXCL-8. Among these markers, VEGF has been proven to suppress renal injury in several experimental studies. VEGF has also been reported to reduce glomerulosclerosis via the suppression of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β in AKI rat models [15]. In addition, MSCs have been shown to inhibit inflammation in kidney disease models through the down-regulation of interleukin (IL) β (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), which was mediated by regulation of the nuclear factor kappa (NF-κB) pathway. Cellular mechanisms of administered MSCs such as transdifferentiation or endocrine effects play a potential role in the regenerative capability of the injured tissues. The protective effects of MSCs occur via suppression of cytokine secretion and increased expression of growth factors including HGF, IGF-I, and VEGF [16], which can effectively ameliorate the damage of the renal cells caused by AKI. Additionally, MSCs can attenuate apoptosis via modulating the thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) pathway, which induces apoptosis of β-cells by activation of the death mitochondrial pathway through the activation of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) [17]. ASK1 is usually bound to thioredoxin 1 (TRX1) under basal conditions. TRX1 is a redox protein that limits cell apoptosis and mitigates reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by oxidative stress, while TXNIP could suppress the antioxidant functions of TRX [18]. TXNIP is a nucleoprotein that can be upregulated by oxidative stress. Under renal damage conditions, TXNIP binds to the TRX1 protein and the ASK1-TRX1 complex is inhibited. The TXNIP-TRX1 complex can suppress the TRX1 protein’s response to ROS, which results in cell apoptosis and oxidative stress [19]. ASK1 is a member of the family of MAPK kinase (MAP3K), and is an activator of p38 MAPK and JNK signaling pathways [7]. ASK1 is activated in response to apoptotic stimuli such as proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and interleukins. Activation of ASK1 leads to several biological responses, including apoptosis, differentiation, and inflammation in different types of cells [20]. Many studies have indicated that MSCs are involved in several molecular mechanisms, including inflammatory response, angiogenesis, ECM remodeling, and apoptosis [21]. In clinical trials with either allogeneic or autologous transplantation of MSCs, no tumorigenicity or severe adverse reactions were found, indicating that MSCs are generally safe in the treatment of several diseases [22]. Nevertheless, clinical applications of MSC treatment still have other limitations, including tissue sources and methods of isolation that can affect MSC differentiation and proliferation. In the present study, we used a cisplatin-induced rat AKI model to examine the potential protective effects of MSCs on the functional and histological injury of AKI and to determine whether the therapeutic effect of MSCs is mediated via their antiapoptotic properties, as well as the underlying molecular mechanisms, focusing on the characterization and homing of MSCs.

Material and methods

Chemicals

Cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)), FUR (4-chloro-N-furfuryl-5-sulfamoyl anthranilic acid), and other chemicals were procured from Sigma Chemicals Company (St. Louis, MO, USA). All kits were purchased from the Egyptian American company, Giza, Egypt.

Husbandry of animals

Twenty-four male albino rats (Rattus norvegicus) with a body weight of 180–220 g were purchased from the Nile Center for Experimental Research, Mansoura, Egypt. All rats were kept in clean polypropylene plastic cages in our laboratory’s animal house under hygienic conditions, temperature 23 ±2°C, and humidity 50–70%, with a 12-hour dark/light cycle. Before initiating any experiment, rats were maintained for 7 days for adaptation, with unrestricted access to chew and water. The experiment was conducted according to the animal ethical regulations and approved by the MSA University Ethics Committee (code: PH8/EC8/2019F).

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell isolation and culture

Whole bone marrow from albino rats’ tibia and femurs (6-week-old males) was flushed, cultured in the Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mmol/l L-glutamine, and purified for up to five passes. After culture for 10 to 12 days, at which the cell confluence reached 80% to 90%, each flask was treated with 1 ml of pancreatin containing 0.25% EDTA for 30 s of incubation and removed. Then, all cells were digested with the pancreatin again at 37°C for 1 min, then treated with 2 to 3 ml of L-DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS [23]. Cells were identified as being bone marrow MSC by their morphology, adherence, and CD surface markers (CD44, CD90, CD105, CD14, CD45, and CD34), using suitable markers, by flow cytometric analysis.

Experimental design and cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury

Acute kidney injury induction in rat model

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, MSA University (code: PB11/REC11/2023PD) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The sample size of this study was calculated using G*Power with a power of 95%, alpha 0.05, and an effect size of 0.95, giving a sample size of 6 rats per group. AKI was induced in rats by administering 5 mg/kg body weight of cisplatin by intraperitoneal injection (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). To examine the therapeutic efficacy of MSCs in the AKI cisplatin-induced animal model, the 24 male albino rats were divided into the following four groups (n = 6): group 1: the control group, rats received a single dose of 0.5 ml of saline by intraperitoneal injection; group 2: the AKI group, rats received a single dose of cisplatin (5 mg/kg body weight) by intraperitoneal injection [24]; group 3: the FUR group, rats received a single dose of cisplatin by intraperitoneal injection and 2 mg/kg FUR twice per week for 2 weeks after the injection of cisplatin [25]; group 4: the MSC group, rats received a single dose of cisplatin by intraperitoneal injection and they were administered with MSCs (5 × 106 cells suspended in 0.5 ml PBS/rat) via the tail vein 24 h after the injection of cisplatin [26].

Sample collection

All animals in our study were sacrificed 2 months after administration of MSCs. All rats were fasted during the night before being slaughtered by diethyl ether anesthesia. Blood samples were drawn from the aortic vein and placed in dry centrifuge tubes before being spun for 5 min at 1200 × g to separate serum. The sera were immediately frozen at –80°C for kidney function testing. After sacrifice, one kidney per rat was removed and rinsed with saline and then stored in 10% formalin to be evaluated histopathologically and immunohistopathologically, while the other kidney was frozen at –80°C for analysis of gene expression.

Characterization and homing of MSCs

MSCs at day 14 are characterized by their fusiform or spindle shape. MSCs are expressed by flow cytometric analysis CD29, CD73, and CD105 on their cell surface, and CD44 by immunohistochemistry.

Evaluation of kidney function tests

The alterations in kidney function were used to estimate the extent of kidney damage and the prognosis. Serum creatinine (Scr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) indicate the degree of impaired glomerular filtration function to a specific extent. These kidney function tests were assayed using the Urea/BUN-spectrum diagnostic kit and Creatinine-spectrum diagnostic kit.

Apoptotic factors: ASK-1 and TXNIP protein expression assay by western blot

The ReadyPrep protein extraction kit (Catalog 163-2086) and Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Bio Basic Inc, Markham, Ontario, Canada, Cat# SK3041) were used for protein isolation and quantification, respectively. The blot findings were presented in autoradiographs using Bio-Rad Image software.

Inflammatory mediators: interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) gene expression assay by real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was first extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (catalog no. 74104, Qiagen, Germany). The cDNA was produced using the Revert Aid Reverse Transcriptase. The SYBR Green PCR kit (catalog no. 204141, Qiagen, Germany) was used to perform RT-PCR with a total reaction volume of 25 µl using primers for each gene, as shown in Table I [27].

Table I

Oligonucleotide sequence of the forward and reverse primers of the inflammatory mediators interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) used for detection of gene expression by RT-PCR

Histopathological assessment

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain was applied to 5 µm sections of paraffin-embedded renal tissues for histological investigation [28], using anti-VEGF rabbit polyclonal Ab (Boster Biological Technology, Pleasanton, CA, USA, Cat.# PA1080).

Immunohistochemical assessment of the angiogenic factor VEGF

The immunohistochemical examinations were carried out according to the technique of Gosselin et al. [29]. HRP with streptavidin was then added after the addition of the secondary antibody to produce the brown color. The area of positive expression was measured using a light microscope (Olympus Software).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software was used to organize, tabulate, and analyze the acquired data statistically. The mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) were calculated. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine differences between the studied groups with the significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

Characterization and homing of MSCs in kidney tissues

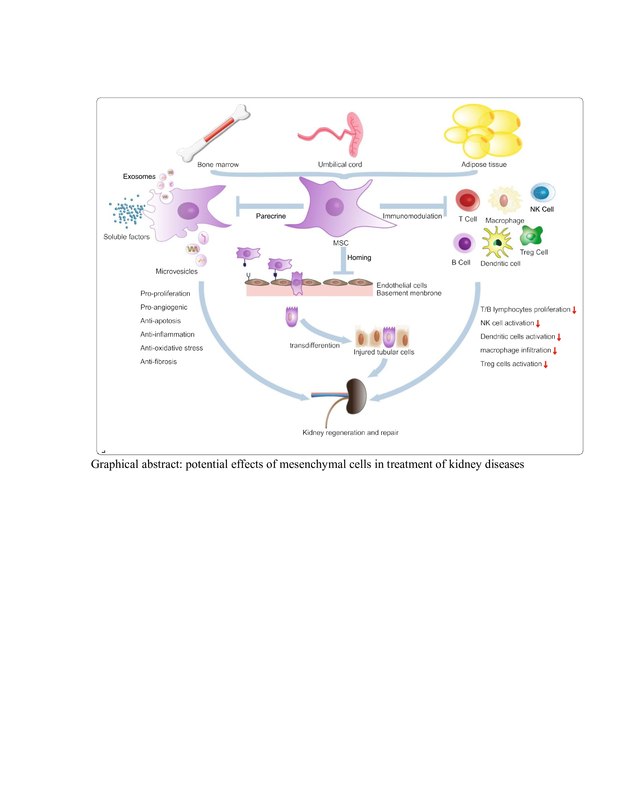

MSCs were characterized by their fusiform shape, fibroblast-like cells, and adhesiveness. Flow cytometric assessment of cell surface markers exhibited positive surface expression of CD73, CD105, and CD29 (Figure 1). The renal sections of the MSC-treated group showed a CD44-positive immunoreactive spindle-shaped cell showing intense brown-colored granules. The positive CD44 cells are located within the cells or in between the renal tubules (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Histograms of flow cytometry showed positive expression of CD29 (A), CD73 (B), and of CD105 (C). Immunohistochemical stained section of renal tubules of MSCs for CD44 at magnification 1000× shows intensive positive reaction in the cytoplasm of spindle shaped MSC which is incorporated as brown colored granules in between renal cells (D)

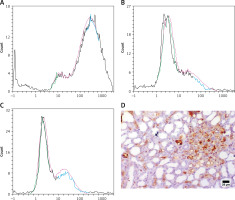

Kidney function damage induced by cisplatin was repaired by MSCs

Treatment with MSCs showed a significant decrease in serum creatinine and BUN levels (p < 0.05) as compared to AKI rats or FUR-treated rats, as illustrated in Figure 2. These data suggested that MSCs can ameliorate kidney function damage induced by cisplatin in rats.

Figure 2

Role of mesenchymal stem cells in alleviating kidney injury in rats. Data were presented as means ± SEM. Each column represented the means ± SEM. Variations between the groups using Turkey’s honestly significant difference test. ap < 0.01 vs. control, bp < 0.01 vs. cisplatin induced acute kidney injury cells, cp < 0.01 vs. furosemide treated cells

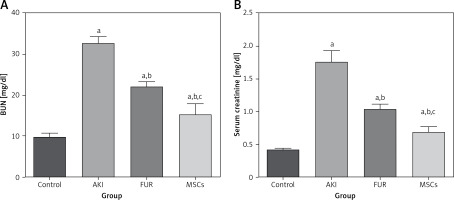

Cisplatin-induced kidney cell apoptosis was inhibited by MSCs

To investigate the mechanism by which MSC treatment attenuated apoptosis, we examined the ASK-1 and TXNIP pathway in the AKI rat model. In the AKI group, kidney apoptosis was associated with a 3-fold increase in ASK-1 expression and a 2-fold increase in TXNIP expression compared with the control group. In contrast, the apoptosis of kidney cells in the MSC group was significantly reduced compared to the AKI group, as indicated in Figure 3. This reduction indicated that MSCs exhibited antiapoptotic properties via the paracrine signaling pathway under specific pathological conditions.

Figure 3

The expression of the anti-apoptotic markers; TXNIP and ASK-1 after treatment with MSCs in AKT. A – The kidney apoptosis was elevated in the AKI group by the elevation of expression levels of ASK-1 and TXNIP by 3 and 2 folds, respectively, compared to the control group. On the contrary, the apoptosis process of kidney cells in the MSCs group was significantly reduced compared to AKI group as indicated in Figure 3. This reduction indicated that MSCs exhibited antiapoptotic properities via paracrine signaling pathway under specific pathological conditions. Data were presented as means ± SEM. Each column represented the means ± SEM. Significant difference was measured by Turkey test; ap < 0.01: significant difference vs. control, bp < 0.01: significant difference vs. cisplatin induced acute kidney injury cells and cp < 0.01: significant difference vs. furosemide treated cells. B – the relative expression of ASK-1 and TXNIP was measured by western blot analysis; 1: control group, 2: AKI group, 3: FUR group, and 4: MSCs group

Cisplatin-induced inflammation in kidneys was reduced by MSCs

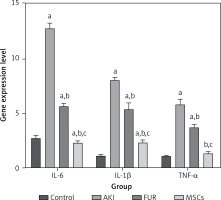

The AKI group showed a highly significant (p < 0.01) elevation in the inflammatory mediators including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β levels as compared to control rats. MSC treatment of AKI rats showed significant suppression of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α (p < 0.01) compared with both FUR and control groups, showing the potential anti-inflammatory effects of MSCs (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Anti-inflammatory effects of MSCs in AKI-induced rat model on IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-a gene expression. AKT group showed a highly significant (p < 0.01) elevation in the inflammatory mediators including TNF-a, IL-6, and IL-1β levels as compared to control rats. MSC treatment of AKI rats showed a significant supression in IL-6, IL-1β and TGF-a (p < 0.01) compared with both FUR and control groups showing the potential anti-inflammatory effects of MSCs. Data were presented as means ± SEM. Each column represented the means ± SEM. Means with different letters indicated the variations between the groups within the same row using Turkey’s honestly significant difference (p < 0.05) test. ap < 0.01 vs. control, bp < 0.01 vs. cisplatin induced acute kidney injury cells, cp < 0.01 vs. furosemide treated cells

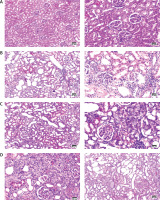

Histopathological observations

H&E stained kidney sections of the control group showed normal tubules and glomeruli with normal Bowman’s capsule. The AKI group stained renal sections showed necrotic renal tubules, mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration, and dilated tubules. Loss of borders was potentially observed in tubules. The FUR group H&E stained sections showed some regenerating renal tubules within the cortex. H&E sections from MSC treated AKI rats revealed numerous regenerating tubules in the renal cortex with mild mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltration when compared to the AKI group or FUR group. The kidney sections appeared similar to the normal control group except that there were mild mononuclear inflammatory cells, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5

H&E stained renal cortex sections at magnification ×400, bar 50 pm. A – control group was stained by H&E showing normal glomeruli and tubules. B – AKI group was stained by H&E showing necrotic renal tubules, mononuclear inflammatory cells infiltration and dilated tubules. C – FUR group was stained by H&E showing some regenerating renal tubules within the cortex. D – MSCs group was stained by H&E showing numerous regenerating tubules in the renal cortex with mild mononuclear inflammatory cells infiltration

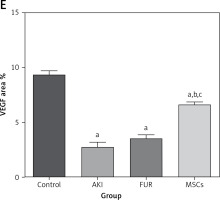

Immunohistochemical analysis of angiogenic factor vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) protein expression

The control group rats revealed a positive strong reaction for VEGF protein expression in kidney sections. The AKI group revealed a mild reaction for expression of VEGF expression in kidney tubules and glomeruli. Upon MSC treatment of AKI rats, a significant positive reaction was observed for VEGF expression in kidney sections compared to control and FUR-treated rats, as shown in Figure 6. These immunohistochemical results highlight the potential angiogenic properties of MSCs in the treatment of several diseases.

Figure 6

Immunohistochemical staining of VEGF of renal cortex sections at magnification ×400, bar 25 µm. A – Immunohistochemical-stained kidney sections of control group showing strong reaction of VEGF protein expression in the renal cortex. B – Immunohistochemical-stained kidney sections of AKI group showing significant reduction in the expression of VEGF in renal medulla. C – Immunohistochemical-stained kidney sections for VEGF protein expression of FUR group showing mild increase in the expression of VEGF in renal cortex. D – Immunohistochemical-stained kidney sections for VEGF protein expression of MSCs group showing marked increase in the expression of VEGF in renal medulla E – The angiogenic effects of MSC in kidney tissue, expressed as area %. Data were presented as means ± SEM. Each column represented the means ± SEM. The mean variations between the groups using Turkey’s significant difference test. ap < 0.01 vs. control, bp < 0.01 vs. cisplatin induced acute kidney injury cells, cp < 0.01 vs. furosemide treated cells

Discussion

Kidney diseases are a public global health problem that affects more than 750 million of the population worldwide and leads to 6 to 10 million deaths yearly [30]. Recently, MSCs have been considered innovative tools for the treatment of kidney diseases due to their homing, migration, and differentiation effects [31, 32]. Previous studies have shown that MSCs are safe and effective when using MSCs for organ injury treatment [33]. Additionally, MSC treatment enhanced the recovery of kidney function after kidney pathogenesis via different mechanisms including anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammation and angiogenesis [34]. In this research, a cisplatin-induced rat AKI model was used to examine the potential protective effects of MSCs on functional and histological kidney injury and to determine whether the therapeutic effect of MSCs is mediated via their antiapoptotic properties as well as the underlying molecular mechanisms.

In our study, MSCs migrated to the damaged kidneys of rats, as evidenced by CD44 expression detected by immunohistochemistry in the renal tissue of the AKI group. These results were confirmed by Morigi et al. [35], who described homing of MSCs in the damaged kidneys. Our results showed that cisplatin strongly suppressed kidney function in diseased rats. This effect may result from the decrease in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) by damaging the distal nephron, which is closely linked to an elevation in serum creatinine levels [36]. Conversely, after injection of MSCs these levels were significantly reduced, indicating that MSCs could effectively repair the kidney function injury that can be induced by cisplatin. These results are confirmed by previous studies [37, 38].

Inflammation plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of AKI [39]. In the current study, the MSCs effectively reduced the elevated levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF gene expression in the AKI group. Renal damage induced by cisplatin contributes to the elevated level of inflammation in the AKI group [40], which plays a crucial role in formation of inflammatory mediators. In the inflammatory pathology, TNF-α is released from damaged tissues, which leads to stimulation of release of IL-β and IL-6 [41]. However, the production of cytokines in rats was significantly reduced after treatment with MSCs, suggesting that MSCs had potential anti-inflammatory properties. This significant elevation in cytokine levels in the AKI group is similar to the observed elevation in rats with nephrotoxicity induced by cisplatin in previous studies [42]. This is thought to be due to the attenuation of kidney urea transporters (UTs), which elevates pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF-α in severe inflammatory conditions [43].

MSCs have been demonstrated to possess potent anti-inflammatory properties, which are mediated through several mechanisms [44]. These mechanisms include the modulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression [45], through the production of anti-inflammatory biomarkers including IL-10, as well as the differentiation into pericytes and endothelial cells [46]. In this study we focused on the essential role of TNF-α in kidney diseases. It can activate apoptosis pathways and cell survival, and stimulate the renal epithelial cells to secrete cell adhesion mediators [47]. It has been reported that TNF-α activates ASK1 by dissociation of ASK1 from its inhibitors 14-3-3 (a phosphoserine-binding molecule) and Trx [48]. In contrast, MSCs inhibit TNF-α–induced ASK1 activation by preventing the release of ASK1 from the binding molecule 14-3-3 [49]. MSCs significantly inhibited this TNF-α apoptotic pathway by reducing TNF-α and apoptotic proteins in the current study; these results agree with those reported by Favero et al. [50].

The potential mechanism by which MSCs reduced ASK-1 and TXNIP expression was suggested by their suppressive effects on cytokine production [51]. This study has shown that AKI leads to elevated expression of these markers. This is likely due to the production of pro-inflammatory pathways via the release of ROS in the kidney tissue [52]. The accumulation of ROS can stimulate a pro-inflammatory state and lead to oxidative stress [53]. This further exacerbates the injury process of AKI and contributes to the activation of ASK-1 and TXNIP, which are key signaling mechanisms in susceptibility to AKI.

Kidney injury causes cascade reactions; the apoptosis of kidney cells is a critical step in the pathogenesis of kidney injury [17]. Kidney cells undergo shedding and apoptosis, which obstructs the lumen. Additionally, other renal cells are subjected to oxidative stress and inflammatory reactions, which leads to tissue damage. Reduction of apoptosis of renal cells is the key main step in kidney injury repair [46]. In this study, the pathogenesis pathway of acute kidney damage caused by cisplatin was found to upregulate apoptosis. However, after treatment with MSCs, expression of the apoptotic factors ASK-1 and TXNIP was significantly reduced in rat renal tissues. These results indicated that MSCs could significantly suppress the apoptosis of kidney cells [54].

Highlighting the angiogenic potential of MSCs, the current study demonstrated a correlation between AKI and VEGF protein expression within the renal medulla. VEGF, a protein known to promote angiogenesis, has a crucial role in the production of new blood vessels [55].

In this study, treatment with MSCs was observed to cause a significant elevation in VEGF expression when compared to the AKI group. These findings are confirmed by the study of Liu and Fang [56]. The pro-angiogenic effects of MSCs are related to the repair of these injured tissues, showing significant elevations of VEGF after treatment. Furthermore, MSCs could stimulate angiogenesis by producing factors related to the angiogenic factors such as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) [57], and this could explain the upregulated VEGF gene expression level in the MSC-treated groups [58].

These results agreed with a previous study conducted by Li et al. [59], which reported elevated levels of VEGF expression in chronic renal failure after MSC transplantation. This suggests that MSCs may enhance angiogenesis by elevation of VEGF protein levels, as previously reported in ischemic stroke [55], hepatic tissue [60], and chronic renal failure [61]. However, Tögel et al. [62] also proposed that MSCs accelerate pyrosis in kidney failure by elevation of proangiogenic cytokines, such as VEGF, raising questions about the effects of MSCs on kidney tissue angiogenesis in AKI. In line with our study, Xu et al. [34] found that MSCs elevated the repair of the renal tubules, which enhanced kidney function. These findings imply that angiogenesis may be a crucial mechanism for the therapeutic effects of MSCs on AKI.

Additionally, we can explain the improvement of AKI by MSC treatment based on the enhancement of histopathological results in the current study. The kidneys of the AKI group showed distorted Bowman’s space and glomeruli with clear hyalinosis. These changes agree with Najafian et al. [63], who stated that an early sign of AKI is histological changes, including the thickening of the glomerular membrane. Histological examination of the AKI group after MSC injection showed that the histology of renal tissue retained almost the normal appearance of the control ones. These results are in line with a study that demonstrated that MSCs can differentiate into and regenerate renal cells [64]. Also, the renal tubules of the MSC group retained their normal structure, and these results also agree with the studies of Qian et al. [65] and Wu et al. [66] which revealed the ability of MSCs to differentiate into tubular cells. As a whole, our data suggest that MSC-based therapy appears to be an innovative intervention approach with tremendous potential for the management of AKI. However, the limitation of our research is that still many in vitro and in vivo studies need to be conducted before MSCs can be applied clinically on a larger scale, in order to enhance their targeting ability and refine their immunomodulatory function.

In conclusion, our data revealed that cell-based therapy using MSCs can alleviate inflammation and apoptosis, and enhance renal function in AKI, suggesting the possibility of treatment with MSCs as an effective and new therapeutic tool for AKI. However, more clinical and preclinical studies should be performed to confirm it in the future.