Introduction

Anaemia is widely considered a major public health problem. This condition has negative effects on health, especially among women of reproductive age (WRA) [1]. The continued prevalence of anaemia generates continual cycles of morbidity and mortality all around the world [1, 2]. The World Health Organization defines anaemia as a haemoglobin (Hb) level of less than 12.0 g/dl for nonpregnant women and less than 11.0 g/dl for pregnant women [3]. Global reports indicate that 29.9% of nonpregnant and 36.5% of pregnant women worldwide had anaemia in 2019, with low-income countries reporting the highest burden [4]. Anaemia is a multifactorial condition that has been attributed in different cases to chronic inflammation, parasitic infection, hereditary disorders, and deficiencies in iron, vitamin B12, and folate. Its prevalence remains excessively high in low- and lower-middle-income countries, exceeding 40% in women of reproductive age [5]. Iron deficiency is considered the leading cause of anaemia. However, other causes, such as infections (e.g. malaria and helminthiasis), genetic blood disorders (e.g. thalassaemia and sickle cell disease), and inadequate healthcare access, significantly increase the burden of anaemia. In addition, socioeconomic disparities, limited varieties of food, and a lack of access to prenatal care can accelerate this problem. To address these factors, it is crucial to design targeted interventions to reduce anaemia prevalence and associated health risks [5].

The complications of anaemia not only degrade individual health but also impact cognitive development, quality of life, and work productivity; they can also increase maternal and neonatal risks, including premature delivery, low birth weight, and stillbirth [6–8]. Although antenatal care programmes prioritise caring for pregnant women by providing vitamin and mineral supplements as well as malaria protection drugs [9–11], nonpregnant women are not covered by these programmes. Although there is an ongoing global effort to reduce the prevalence of anaemia, progress has been slow and globally uneven globally. One notable target set by the WHO is to reduce anaemia prevalence among WRA by 50% by 2030 (following the original, failed target of 2025) [12].

The EMR is characterised by broad variation in economic status across different countries, which leads to disparities in anaemia prevalence. Many studies have examined anaemia among different populations in the EMR, noting considerable disparities in trends and prevalence. For example, researchers have reported a high burden of anaemia among pregnant women, nonpregnant women, children, and the elderly [13–17]. Other research has focused on the effects of socioeconomic factors on anaemia prevalence [18–20]. While there have thus been many studies of anaemia in the EMR, most have been limited to small sample sizes or specific subpopulations. Only a few have considered the role of national income in shaping anaemia prevalence [21].

The present study helps fill these gaps by pursuing three main objectives. First, it analyses the prevalence of anaemia among pregnant and nonpregnant women aged 15–49 years in the EMR. Second, it investigates the relationships between income and anaemia prevalence and changes throughout the period 2000–2019. Finally, it compares country-specific patterns of anaemia prevalence in pregnant and nonpregnant women.

Material and methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study consulted WHO data representing 21 countries in the EMR from 2000 to 2019. Specifically, data on WRA were extracted and classified according to pregnancy status (pregnant vs. nonpregnant). The countries deemed to belong to the EMR were determined according to the WHO’s classification, and the WHO also provided estimates of anaemia rates based on national surveys and modelling tools. Data on country incomes, in contrast, were taken from the World Band’s records for 2023. The methodology of this study is similar to that of our previous research [22].

Variables and definitions

In this study, anaemia was defined as a haemoglobin (Hb) level of less than 120 g/dl for nonpregnant women and less than 110 g/dl for pregnant women. Country incomes were categorised into four groups according to the 2023 classification of the World Bank: low income, lower middle income, upper middle income, and high income. This classification is updated annually by the Word Bank, but we used the most recent income classification (2024), following the usual conventions of global health studies.

Pregnancy status was determined in a binary fashion: Women were classified as either pregnant or not pregnant. Data were extracted for the period from 2000 to 2019 and aggregated into 5-year intervals (2000–2005, 2005–2010, 2010–2015, and 2015–2019) to assess temporally specific trends.

Data sources

The data on anaemia prevalence that we consulted are publicly available on the WHO’s website at https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/anaemia-in-nonpregnant-women-prevalence-(-) and https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/prevalence-of-anaemia-in-pregnant-women-(-). The country income classification is publicly available on the World Bank’s website: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledge-base/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

Analytical phase

The first step of the analysis involved extracting data on anaemia prevalence in the two study groups (pregnant and nonpregnant women) from the WHO’s website and data on national incomes from the World Bank’s website. The data on anaemia prevalence were then correlated with the information on country income. The relative and absolute changes in anaemia prevalence as well as annual reductions were calculated for the study period at 5-year intervals. We then compared the trends in anaemia prevalence among pregnant and nonpregnant women.

Ethical considerations

The study was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study used publicly available, anonymous data and thus did not require formal ethical approval.

Statistical analysis

To conduct the statistical analysis, we used IBM SPSS v28, Microsoft Excel, and Graph Pad Prism for Windows (version 5.0, San Diego, CA; www.graphpad.com, SCR_002798). Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables, are used to summarise the data. We tested the assumption of normality of variances using the Shapiro-Wilk test and visual inspection of a histogram. The data did not follow a normal distribution, so a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparisons. The Kruskal-Wallis test and analysis of variance were used to analyse the associations between anaemia prevalence and income category. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. These statistical methods were selected to match the distribution of the data, thereby ensuring an appropriate analysis.

Results

Anaemia prevalence: trends for the period 2000–2019

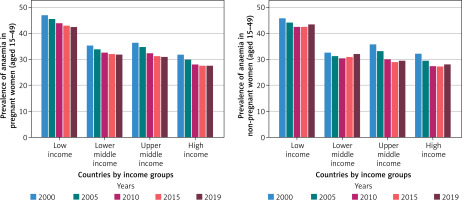

Our analysis revealed notable trends and shifts in the prevalence of anaemia among pregnant and nonpregnant women aged 15–49 years in 21 EMR countries between 2000 and 2019. The prevalence of anaemia in both pregnant and nonpregnant women decreased overall throughout the study period. In pregnant women, the average prevalence decreased from 37.6% in 2000 to 33.0% in 2019. This decline marks an absolute change of –4.6 points and a 12% relative reduction. The mean prevalence among nonpregnant women decreased from 36.7% in 2000 to 33.1% in 2019. This marks an absolute change of –3.6 points and a 10% relative drop (Table I).

Table I

Mean anaemia prevalence (%) according to income class in the EMR from 2000 from 2019

Reductions in anaemia throughout the EMR have not been consistent over the past two decades. The greatest decline in prevalence among pregnant and nonpregnant women occurred between 2000 and 2010. The prevalence of anaemia decreased only slightly over the second decade (Table I). Although there were reductions in both study groups, the change among nonpregnant women was consistently higher than that in pregnant women (–12% vs. –10%). Furthermore, anaemia prevalence was consistently higher in low-income countries (Figure 1) than in high-income countries (Figure 2).

Prevalence of anaemia by national income

The greatest anaemia burden was reported by low-income countries. In 2000, the mean prevalence of anaemia among both pregnant and nonpregnant women exceeded 45%. By 2019, the prevalence had decreased by 9% in pregnant women and 5% in nonpregnant women (Table I). Conversely, countries with higher incomes reported a lower anaemic burden. In 2000, the average prevalence was 31.8% in pregnant women and 32.1% in nonpregnant women. By 2019, the prevalence had decreased by 13% in both pregnant and nonpregnant women (Table I).

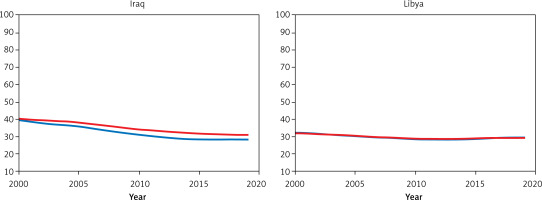

Upper-middle-income countries reported varying rates of improvement (Figure 3). From 2000 to 2019, Iraq reported –23% and –28% changes for pregnant (Table II) and nonpregnant women, respectively (Table III). In the same income group, Libya reported a –9% relative change in pregnant women (Table II) and a –8% relative change in nonpregnant women (Table III). Lower-middle-income countries exhibited a variety of patterns (Figure 4). For example, both Djibouti and Egypt experienced relative changes of –13% in pregnant women and –21% in nonpregnant women over the research period. Jorden reported a relative change of 2% in pregnant women and 26% in nonpregnant women (Tables II and III).

Table II

Anaemia among pregnant women in the EMR from 2000 to 2019: prevalence, absolute change, and relative change

Table III

Anaemia among nonpregnant women in the EMR from 2000 to 2019: prevalence, absolute change, and relative change

Figure 3

Anaemia prevalence among pregnant vs. nonpregnant women in upper middle income countries in the EMR from 2000 to 2019

Figure 4

Anaemia prevalence among pregnant vs. nonpregnant women in lower middle income countries in the EMR from 2000 to 2019

This analysis revealed a strong inverse association between the prevalence of anaemia and country income among both pregnant and nonpregnant women for the entire study period (2000–2019) (p = 0.001) (Table IV). When individual time points were examined, the same substantial inverse correlation was observed most of the time. In pregnant women, a considerable gap between anaemia prevalence and country income group persisted across all time points analysed (p = 0.015, 0.014, 0.028, 0.018, and 0.029 for 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2019, respectively). In nonpregnant women, a similar gap was found at most time intervals (p = 0.030, 0.017, and 0.017 for 2010, 2015, and 2019, respectively), with marginal, nonsignificant correlations observed in 2000 and 2005 (p = 0.108 and 0.07, respectively) (Table IV).

Table IV

Analysis of anaemia prevalence by income groups across different periods using Kruskal-Wallis H test and ANOVA

Country-specific patterns by pregnancy status

Our comparative analysis revealed notable country-specific patterns and differences. In 2000, the average prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women was 37.6%, compared to 36.6% among nonpregnant women, and by 2019, this prevalence had dropped to 33.0% for pregnant women and 33.1% for nonpregnant women (Figure 5). During the study period, the relative change was –12% for pregnant women and –10% for nonpregnant women (Table I).

Figure 5

Trends in the prevalence of anaemia among pregnant and nonpregnant women in countries in the EMR from 2000 to 2019

In low-income countries (Figure 1), the two study groups had consistently high anaemia rates. In Yemen and Somalia, pregnant women had a 50% prevalence, yet in 2019, the relative changes were only -4% and -5%, respectively, indicating minimal progress (Table II). Nonpregnant individuals in Yemen reported an approximately 60% prevalence, while Somalia’s was approximately 40% (Table III).

Iraq and Oman exhibited the most remarkable improvement. From 2000 to 2019, Iraq saw relative changes of –23% for pregnant women and –28% for nonpregnant women. Oman achieved relative changes of –21% for pregnant women and –23% for nonpregnant women (Tables II and III). Jorden demonstrated a pattern of stagnation, with the prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women changing from 33.2% in 2000 to 33.7% in 2019 – a 2% increase – while the prevalence among nonpregnant women increased from 30.2% to 38%. A similar example is Pakistan, which saw a rise in the prevalence of anaemia among nonpregnant women (39.8 in 2000 to 41.1 in 2019), whereas the prevalence among pregnant women decreased (from 48.5% in 2000 to 44%).

Although high-income countries maintained low prevalence rates, an unexpected pattern was noted (Figure 2). The United Arab Emirates made no progress in reducing anaemia among nonpregnant women (24.3% between 2000 and 2019), while in Kuwait, the prevalence among pregnant women decreased from 25.4% in 2000 to 23.7% in 2019.

Afghanistan, a low-income country, demonstrated a unique pattern (Figure 1), with a significant drop in anaemia (18%) among pregnant women between 2000 and 2019 (44.4% to 36.5%). The same country saw a 26% increase among non-pregnant women, from 34.2% in 2000 to 43.2% in 2019 (Tables II, III). This trend was also observed in Lebanon, a lower-middle-income country (Figure 4), where the prevalence decreased among pregnant women but increased by 7% among nonpregnant women (Table III).

Discussion

This study examined the prevalence of anaemia and changes therein among pregnant and nonpregnant women in 21 EMR countries from 2000 to 2019, noting associations between prevalence and national income. Our research revealed a general improvement in anaemia rates among both study populations over the study period, even though the prevalence of anaemia remains high, particularly in low-income nations. The drop in prevalence was more evident in the first decade (2000–2010), whereas the second decade witnessed stagnation – particularly in low-income nations, where pregnant women underwent a greater relative reduction than nonpregnant women. This result is consistent with earlier research, which indicated a decrease in anaemia prevalence during this period [5, 21].

Many factors may have contributed to the stagnation in the second decade, including decreases in global health interventions pertinent to anaemia, in the implementation of food fortification programmes, in the supplementation of food with iron and folic acid, and in the administration of malaria control programmes [23, 24]. The consistently observed gap between prevalence rates in pregnant and nonpregnant women warrants further exploration, as this may point to physiological and dietary differences between the two study groups [1, 25, 26]. It could also indicate disparities in healthcare access between these groups.

This research revealed a substantial inverse relationship between national income and anaemia prevalence (p < 0.001). Low-income countries have a higher prevalence of anaemia [27–29]. In 2000, the mean prevalence of anaemia in both groups exceeded 45%. Although these countries reported some progress, after two decades, they achieved a relative change of less than –10% for both pregnant and nonpregnant women. High-income countries achieved greater anaemia reductions in both groups by 2019.

This indicates the crucial role of socioeconomic status in determining health [5, 30, 31]. Low-income countries face many challenges in this respect, such as food supply insecurity, poor healthcare for women, limited access to nourishing food, and insufficient infrastructure for health services [32–34]. On the other hand, high-income countries provide strong healthcare services, an adequate food supply, and extensive anaemia prevention efforts [6, 35, 36]. These disparities warrant urgent and targeted interventions to reduce anaemia rates.

This study revealed significant gaps between economic groups. For example, among the upper-middle-income class, Iraq reported a significant drop in anaemia prevalence among both pregnant and nonpregnant women, indicating a positive effort to enhance health services. In the same income class, however, Libya achieved a smaller reduction in both groups. This may reflect sociopolitical instability in Libya during the study period [37, 38]. These disparities also characterised lower-middle-income countries. For example, Egypt reported a notable decrease in both pregnant and nonpregnant women, and this reduction was greater among pregnant women. In the same income group, Jordan saw stagnation in the prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women and a notably worse prevalence among nonpregnant women. These disparate trends may reflect differences in the provision and implementation of health service programmes [39, 40].

Throughout the study period, the prevalence of anaemia in nonpregnant women was consistently higher than that in pregnant women, although this gap decreased over time. This disparity between the two groups may indicate prioritisation of pregnant women in health service programmes, such as antenatal care involving the provision of folic acid and iron supplements [41–43]. This high prevalence of anaemia in nonpregnant women suggests that healthcare programmes should devote greater attention to these individuals. Furthermore, large-scale health strategies should be implemented, including all WRA, in efforts to prevent anaemia. After all, they could become pregnant in the future.

Many nations, including Iraq, Oman, and Saudi Arabia, have achieved substantial progress in reducing anaemia prevalence. This accomplishment may be attributed to the successful strategies used to address this challenge, such as screening and treating procedures, nutrition fortification programmes, increases in nutritional diversity, and investments in antenatal care services [44–49]. On the other hand, nations such as Jordan exhibit concerning trends, with anaemia frequency increasing among both pregnant (2%) and nonpregnant (26%) women. Studies have identified many important determinants of anaemia prevalence, including educational factors; limited health resources, health facilities, medical services [50–52], and access to nutritional knowledge; and folate deficiency [53].

Although the prevalence of anaemia has generally decreased in high-income nations, unexpected trends were observed in some countries. For example, the United Arab Emirates did not demonstrate any progress in reducing anaemia among nonpregnant women across the whole study period. Similarly, Kuwait reported a minimal decline in anaemia among nonpregnant women. This could indicate that anaemia rates are influenced by more than just national income. This lifestyle could also be induced by poor dietary habits, an increasing rate of obesity, chronic diseases [49, 54–59], or a lack of adherence to WHO recommendations. Vitamin D and iron deficiencies have also been associated with anaemia [60]. One study reported that half of the healthy Emirati population has abnormal complete blood count values [61].

Anaemia in Afghanistan exhibits a unique pattern. Although the prevalence has decreased substantially among pregnant women in this country (–18%), there was a rise among nonpregnant women (26%). This paradoxical trend may imply improved antenatal care but limited success in dealing with anaemia concerns among nonpregnant women [62–64], as well as high levels of poverty and food insecurity [65]. We also found a study from Afghanistan that supports a link between sheep ownership and anaemia risk [66]. Similarly, the prevalence decreased among pregnant women but increased among nonpregnant women.

There is an urgent need for targeted interventions to minimise anaemia. These interventions should be tailored to the relevant country’s health and economic circumstances. In low-income nations, large-scale food fortification programmes have demonstrated success in reducing anaemia prevalence [67]. Developing community-based food supplementation programmes and improving prenatal care can also help reduce this prevalence [68, 69]. In lower-middle-income countries, such as the Philippines, Tanzania, Nigeria, and India, programmes such as school-based iron supplementation and deworming have been shown to reduce anaemia [70, 71]. Such programmes could be used elsewhere under similar circumstances. Upper-middle-income countries, such as Malaysia, have shown success in integrating national educational strategies for anaemia prevention into broader maternal and child health initiatives, significantly diminishing anaemia rates [72]. In high-income countries, where anaemia may be linked to dietary habits and chronic disease, the focus should be on ensuring regular medical check-ups, implementing educational programmes about nutritional balance, and addressing obesity-related micronutrient deficits.

This study provides important insights regarding the prevalence of anaemia in the EMR, but several limitations should be acknowledged. This study is based on WHO data, which may have been subject to bias when being collected and reported. Variation in methodologies as well as disparities between the quality of national surveys may have led to inaccuracies in the estimations of anaemia prevalence, especially in areas affected by conflict or those with limited resources. Furthermore, these data do not take into account cultural and sociodemographic data that can help assess the prevalence of anaemia, such as nutritional habits, access to health services, and treatment-seeking behaviours. Furthermore, this study does not differentiate between nutritional and non-nutritional causes of anaemia, and it does not consider the severity of the cases. The exclusion of these potential determinants may have led to an incomplete understanding of the underlying causes of trends in anaemia prevalence.

In conclusion, this study emphasises the lingering burden of anaemia among pregnant and nonpregnant women in the EMR, revealing significant variation by pregnancy status and country income. Although the overall prevalence of anaemia decreased between 2000 and 2019, there were discrepancies in this progress. In particular, low-income countries lagged behind in anaemia prevention efforts.

These data emphasise the need for immediate and continuous country-specific strategies to address this concern, particularly among nonpregnant women, who consistently exhibit a higher anaemia prevalence. Implementing food fortification programmes, ensuring a continuously secure food supply, improving health services, and providing nutritional supplements are all important steps in reducing anaemia prevalence. Furthermore, the stagnation observed in some high-income nations highlights the significance of immediate monitoring and the implementation of targeted interventions to address this condition. Furthermore, the implementation of general health programmes to prevent anaemia in women of reproductive age is critical for improving women’s health.