Introduction

Chronic respiratory diseases impose a substantial global health burden, characterized by high incidence and mortality rates and incurring considerable socioeconomic costs [1–5]. According to the World Health Organization, as of 2019, asthma affected 262 million people globally, whereas chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) afflicted over 200 million [6]. The prevalence of bronchiectasis is also increasing worldwide [4, 7–10]. Furthermore, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive disease characterized by scarring and stiffening of lung tissue, ultimately leading to a permanent decline in pulmonary function [11]. Each year, there are approximately 40,000 new IPF diagnoses across Europe [12]. Moreover, nearly one billion people worldwide are impacted by obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) [13], with prevalence rates of 24% in men and 9% in women aged 30–60 [14, 15]. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), meanwhile, exhibits a global prevalence of approximately 1%, rising to 10% among those aged 65 and above [16].

Despite significant advancements in management and diagnosis [17–19], standard treatments for chronic respiratory diseases still remain insufficiently effective or have multiple adverse drug reactions for a substantial segment of patients, markedly affecting their quality of life [20]. Consequently, it is crucial to identify modifiable risk factors and explore potential therapeutic strategies to mitigate disease progression and prevent onset, with physical activity (PA) and leisure sedentary behaviors (LSB) being among these key factors.

Rehabilitation training, recognized as a vital component of treatment in the international guidelines for COPD, has been acknowledged for its beneficial effects. For instance, a minimum of 26 min per week of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) has been proposed as an attainable and beneficial objective for patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) [21]. In a 2013 randomized trial, Carson et al. found that physical training significantly improved fitness in individuals aged eight and older with asthma [22]. However, another randomized controlled trial in adults with severe asthma produced incongruent results, indicating that MVPA and MVPA bouts lasting > 10 min were associated with a deterioration in health-related quality of life [23]. Among individuals with bronchiectasis, reductions in PA and an increase in LSB over 1 year were associated with increased frequencies of acute exacerbations [24]. Collectively, these studies highlight the complex interplay between PA and chronic respiratory diseases, underscoring a critical need for more definitive research to elucidate this relationship.

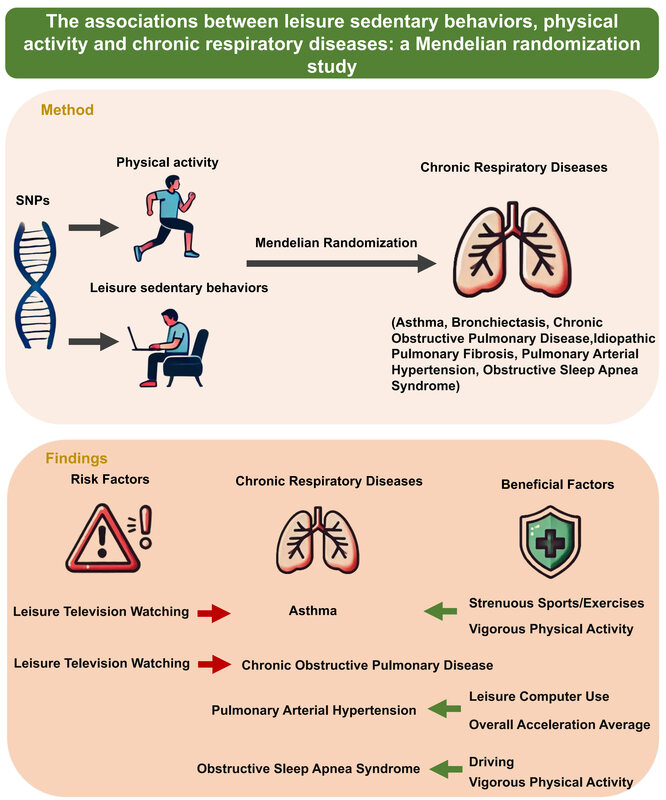

This study aims to ascertain the impact of PA and LSB on chronic respiratory diseases, which will aid in developing targeted and feasible strategies to reduce the risk of these conditions. While previous observational studies have employed various statistical techniques to control for potential confounders [25, 26], these methods remain susceptible to residual confounding and reverse causation, posing challenges in identifying replicable causes of chronic respiratory diseases [27]. In contrast, Mendelian randomization (MR) leverages single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables (IVs), providing a more robust framework for examining the causal effects of specific exposures on outcomes [28, 29]. Due to the random assortment during meiosis and the fixed allocation of genetic variants at conception, MR inherently minimizes the risks of reverse causation and confounding variables that are difficult to address in traditional observational analyses. This approach not only strengthens the evidence for a causal relationship between PA, LSB, and chronic respiratory disease but also offers a novel way to disentangle correlation from true causation in epidemiological research.

This study used SNPs related to PA and LSB, selected from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) conducted by prominent international consortiums [30, 31]. A two-sample MR design was implemented to explore the influence of PA and LSB on the susceptibility of six prevalent chronic respiratory diseases: asthma, bronchiectasis, COPD, IPF, PAH, and OSAS. In contrast to prior research [32–34], which predominantly focused on a single respiratory disease, our study provides a more comprehensive evaluation by encompassing multiple chronic respiratory conditions that have not been thoroughly addressed in the literature. Furthermore, the outcome variables in this study are drawn from meta-analysis GWAS summary statistics or the latest database, affording a larger sample size and thereby enhancing the robustness and generalizability of our findings.

This study employed a two-sample MR analysis to establish the genetic causal relationship between PA, LSB, and chronic respiratory diseases. The findings provide valuable insights for the development of effective preventive intervention strategies for chronic respiratory diseases.

Material and methods

Study design

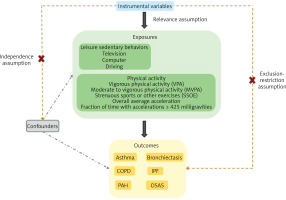

MR analysis rests on three essential assumptions to ensure its validity as an instrumental variable analysis method: (1) the relevance assumption necessitates a robust association between the genetic variants and the targeted exposure; (2) the independence assumption requires that the genetic variants are not correlated with any confounders of the exposure-outcome relationship, ensuring that the observed associations are not confounded by external variables; (3) the exclusion-restriction assumption stipulates that the genetic instruments affect the outcome solely through the exposure, without any direct pathways influencing the outcome outside of the exposure. This selection process ensures the reliability and validity of the MR analysis in deducing causal relationships.

Figure 1 illustrates the framework of a two-sample MR analysis, in which genetic variants related to LSB and PA are employed as IVs. LSB are categorized into three groups – television, computer, and driving – while PA is grouped into five categories: self-reported vigorous physical activity (VPA), self-reported MVPA, self-reported strenuous sports or other exercises (SSOE), accelerometer-measured overall average acceleration, and accelerometer-assessed fraction of time with accelerations exceeding 425 milligravities (mG). The main objective of the study was to elucidate the causal relationships between LSB, PA, and chronic respiratory diseases (asthma, bronchiectasis, COPD, IPF, PAH, OSAS).

Figure 1

Study overview. Instrumental variables, predominantly SNPs, associated with LSB and PA were chosen to estimate the causal effects on chronic respiratory diseases. The selected IVs were required to satisfy stringent criteria: they must exhibit robust associations with the exposure, be independent of confounders of the exposure and outcome, and exert their impact on the outcome exclusively through the exposure

COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IPF – idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, PAH – pulmonary arterial hypertension, OSAS – obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, IVs – Instrumental variables, SNPs – single nucleotide polymorphisms.

Data source of exposures: LSB and PA

Genetic instruments associated with LSB were identified from the GWAS that included 408,815 participants of European ancestry from the UK Biobank [31]. At the initial assessment, 45.7% of the participants were male, with an average age of 57.4 years (standard deviation [SD] = 8.0). Sedentary time was measured through self-reported daily hours engaged in three activities: watching television, leisure-time computer use (excluding work-related use), and driving. On average, participants reported 2.8 h for watching television (SD = 1.5), 1.0 h for leisure-time computer use (SD = 1.2), and 0.9 h for driving per day (SD = 1.0). A mixed linear model was employed to adjust for population structure and cryptic relatedness, with adjustments for age, sex, population stratification and genotyping array. Only genetic loci meeting the genome-wide significance threshold of p < 1 × 10–8 were retained for use in this study. The summary data are publicly accessible at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/publications/32317632.

Sourced from the UK Biobank, we utilized the largest currently available GWAS on PA, drawing exclusively on participants of white European ethnicity [30]. Both self-reported and accelerometer-based measures were used to classify and assess PA levels. Self-report PA was categorized into MVPA, VPA, and SSOE. A touchscreen questionnaire captured self-reported PA data, quantifying the frequency and intensity of moderate PA (MPA) and VPA. Participants who chose “prefer not to answer” or “do not know”, reported an inability to walk, or exceeded 16 h of MPA or VPA were excluded. To quantify MVPA, the total minutes of MPA and VPA were multiplied by four and eight, respectively, and then summed to reflect their respective metabolic equivalents. 377,234 participants were included in the MVPA analysis. For VPA, participants were categorized into those with no VPA (0 days/week) versus those engaging in vigorous activity on three or more days per week (≥ 25 min each session). Individuals not fitting these categories were excluded, leading to the inclusion of 98,060 cases and 162,995 controls in the VPA analysis. The SSOE category was determined based on self-reported frequencies and duration of “strenuous exercise” and “other exercises” over the past 4 weeks. Participants performing ≥ 2–3 days/weeks of these activities, each session lasting 15–30 min, were included among the SSOE cases (N = 124,842), whereas those reporting no such activities in the past 4 weeks served as controls (N = 225,650).

For the accelerometer-based assessment, participants wore Axivity AX3 wrist-worn devices for up to 7 days, enabling the collection of overall average acceleration and the fraction of accelerations > 425 mG – a threshold corresponding to approximately 6 METs of energy expenditure and representing VPA. Individuals with < 3 days of valid recordings, missing data for each hour in the 24-hour cycle, or outliers exceeding four standard deviations above the mean were excluded, ultimately yielding 91,084 participants for overall average acceleration and 90,667 participants for fraction of accelerations > 425 mG. Full summary data for this study can be accessed at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/publications/29899525, and additional details regarding the datasets are listed in Supplementary Table SI.

Data source of outcomes: chronic respiratory diseases

In this research, we selected asthma, bronchiectasis, COPD, IPF, PAH and OSAS as the chronic respiratory diseases. The latest published GWAS summary statistics meta-analysis, conducted by the Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative (GBMI) [35], provided the pertinent data for asthma, COPD, and IPF. This comprehensive analysis encompasses 95,554 cases of asthma and 833,538 controls from 14 databases, 54,606 cases of COPD and 887,000 controls from 12 datasets, and 6,257 cases of IPF and 947,616 controls from 9 biobanks. The complete statistics of the GBMI dataset are accessible at https://www.globalbiobankmeta.org/.

Additionally, genetic data were obtained from the 10th edition of the FinnGen Biobank for 2,372 cases of bronchiectasis and 338,303 controls, 248 cases of PAH and 289,117 controls, and 46,975 cases of OSAS and 365,206 controls. These data can be freely accessed at https://finngen.gitbook.io/documentation/data-download. To avoid the pleiotropic effects of cross-lineage cases [36], we exclusively used data from participants of European ancestry. Further details regarding the datasets can be found in Supplementary Table SI.

Selection of instrumental variables

Prior to MR analysis, a rigorous protocol must be followed to ensure the reliability and robustness of SNPs. First, SNPs were screened based on a genome-wide significance threshold of p < 5 × 10–8, ensuring that SNPs were significantly associated with the exposure. Second, to mitigate the influence of linkage disequilibrium (LD) clumping among IVs, SNPs were clumped using standard parameters (clumping window of 10,000 kb and LD r2 cutoff of 0.001). Third, SNPs significantly associated with the outcomes (p < 5 × 10–8) were eliminated. Fourth, harmonization processes were conducted to exclude palindromic and incompatible SNPs. Fifth, the GWAS catalog database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/home) was used to assess each SNP associated with potential confounding traits, and such SNPs were manually excluded, followed by re-analysis to uphold the independence assumption. Details of potential confounding traits and excluded SNPs are documented in Supplementary Tables SII and SIII, respectively. Sixth, the MR-Pleiotropy Residual Sum and Outlier (MR-PRESSO) test was applied to identify any horizontal pleiotropy and correct outliers that could bias MR results. Following the exclusion of outlier SNPs, MR analysis was re-evaluated to ensure robustness [37]. Supplementary Table SIV lists the outlier SNPs identified. Lastly, the F-statistic is commonly employed to assess the strength of IVs, with values below 10 indicating weak instrument bias. SNPs with F-statistics below this threshold were excluded.

MR analysis and sensitivity analysis

To investigate the causal relationship between exposures and outcomes, five commonly used MR methods were mostly employed: MR Egger, weighted median, inverse variance weighted (IVW), simple mode, and weighted mode. The Wald ratio method is employed when only one SNP is available. MR Egger can yield unbiased estimates when some genetic variants are invalid instruments but is sensitive to weak instruments, potentially resulting in estimation bias [38]. The weighted median method can provide unbiased causal effect estimates even with up to 50% invalid instruments, demonstrating considerable robustness [39]. The IVW method integrates the Wald ratios of each SNP to obtain a composite causal estimate, and conducts a weighted linear regression of the associations among the IVs. Notably, the IVW approach is applicable even when only two SNPs are available. If the results from these methods diverge, the IVW result is prioritized.

Moreover, sensitivity analyses were performed to ensure the authenticity and reliability of the findings. Horizontal pleiotropy, where genetic variations directly influence an outcome through pathways independent of the expected exposure, was assessed using the MR Egger intercept. A lack of significant horizontal pleiotropy was inferred if the intercept p-value exceeded 0.05. Heterogeneity was assessed using Cochran’s Q statistic, applicable to both MR-Egger and MR-IVW methods. A p > 0.05 indicated no significant heterogeneity. When only two SNPs were available, the MR-IVW method was exclusively used.

Additionally, funnel plots, scatter plots, and leave-one-out analyses were performed to assess the reliability of the causal estimates. Funnel plots graphically depict the causal effect estimates of each SNP with its precision, offering a visual assessment of potential asymmetry. Scatter plots illustrate strength and direction of the instrumental variables’ effects and examine the linearity of the causal effects. Leave-one-out analysis sequentially removes each SNP and recalculates the IVW estimate to detect the influence of individual SNPs on the overall causal estimate. Significant changes in causal estimates after removing an SNP suggest its potential outlier status. A minimum of three SNPs is required to conduct this analysis effectively.

Results

Overview

After implementing stringent quality control measures, we identified independent SNPs significantly associated with the exposures (p < 5 × 10–8, r2 < 0.001). Supplementary Tables SV and SVI detail the F-statistic for each SNP, which ranged from 66.004 to 288.378, indicating the low likelihood of weak instrument bias. The number of SNPs used for each phenotype and its corresponding outcome varied, ranging from 1 to 80, as detailed in Supplementary Tables SVII–SXII. Given the binary outcomes employed in this study, MR estimates were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) to ensure statistical precision.

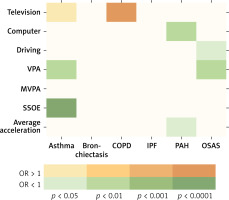

Figure 2 depicts the eight statistically significant causal relationships (p < 0.05 in IVW), including the associations of leisure-time television watching, VPA, and SSOE with asthma; leisure-time television watching with COPD; leisure-time computer use and overall average acceleration with PAH; and driving and VPA with OSAS.

Figure 2

Causal effects of LSB, PA, and chronic respiratory diseases. This figure illustrates the significant causal relationships, denoted by p < 0.05 of IVW, between LSB, PA, and chronic respiratory diseases

VPA – vigorous physical activity, MVPA – moderate to vigorous physical activity, SSOE – strenuous sports or other exercises, COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IPF – idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, PAH – pulmonary arterial hypertension, OSAS – obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, IVW – inverse variance weighted.

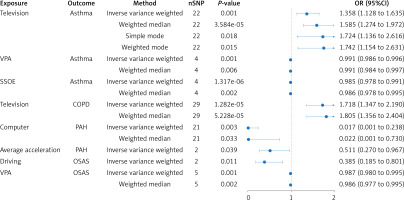

MR estimates

Significant MR results from the IVW method (p < 0.05) are presented in Table I. The IVW method demonstrated that leisure-time television watching was significantly associated with increased asthma risk (OR = 1.358; 95% CI: 1.128–1.635; p = 0.001). Parallel analyses using the weighted median (OR = 1.585; 95% CI: 1.274–1.972; p = 3.584E–05), simple mode (OR = 1.724; 95% CI: 1.136–2.616; p = 0. 018) and weighted mode (OR = 1.742; 95% CI: 1.154–2.631; p = 0. 015) support this finding. Additionally, VPA (OR = 0.991; 95% CI: 0.986–0.996; p = 0.001) and SSOE (OR = 0.985; 95% CI: 0.978–0.991; p = 1.317E–06) were identified as protective factors. Supplementary Table SVII presents the weighted median analysis, which indicates a nominally significant protective influence for both VPA (OR = 0.991; 95% CI: 0.984–0.997; p = 0.006) and SSOE (OR = 0.986; 95% CI: 0.978–0.995; p = 0.002). Furthermore, the primary IVW analysis revealed a detrimental effect of leisure-time television watching on COPD (OR = 1.718; 95% CI: 1.347–2.190; p =1.282E–05), corroborated by weighted median (OR = 1.805; 95% CI: 1.356–2.404; p = 5.228E–05) in Supplementary Table SVIII. Meanwhile, leisure-time computer use (OR = 0.017; 95% CI: 0.001–0.238; p = 0.003) and overall average acceleration (OR = 0.511; 95% CI: 0.270–0.967; p = 0.039) were found to have a protective effect on PAH in the IVW analysis. A similar trend for computer use was also observed in the weighted median analysis, as shown in Supplementary Table SIX (OR = 0.022; 95% CI: 0.001–0.730; p = 0.033). For OSAS, both driving (OR = 0.385; 95% CI: 0.185–0.801; p = 0.011) and VPA (OR = 0.987; 95% CI: 0.980–0.995; p = 0.001) show protective associations, with weighted median analysis yielding a significant protective effect for VPA (OR = 0.986; 95% CI: 0.977–0.995; = 0.002), as detailed in Supplementary Table SX. However, no causal association was detected between LSB, PA, IPF, or bronchiectasis using the IVW analysis (Supplementary Tables SXI and SXII). Figure 3 presents forest plots illustrating the range of meaningful causal estimates.

Table I

MR results regarding the causal impact of PA and LSB on chronic respiratory diseases

[i] P < 0.05 represents a causal association. MR – Mendelian randomization, SNPs – single nucleotide polymorphisms, OR – odds ratio, CI – confidence interval, VPA – vigorous physical activity, SSOE – strenuous sports or other exercises, COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IPF – idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, PAH – pulmonary arterial hypertension, OSAS – obstructive sleep apnea syndrome.

Figure 3

Forest plots illustrating the meaningful estimated causal effects of LSB, PA, and chronic respiratory diseases. The MR estimates derived from the IVW, weighted median, simple mode, and weighted mode

VPA – vigorous physical activity, MVPA – moderate to vigorous physical activity, SSOE – strenuous sports or other exercises, COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IPF – idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, PAH – pulmonary arterial hypertension, OSAS – obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, MR – Mendelian randomization, SNP – single nucleotide polymorphism.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity studies, Cochran’s Q test, and the MR-Egger intercept test were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the aforementioned conclusions. The MR-Egger intercept remained near zero (p > 0.05), suggesting minimal risk of horizontal pleiotropy. Nevertheless, Cochran’s Q test indicated heterogeneity (Q_p val < 0.05) in several associations, including leisure-time television watching with asthma (p = 0.008 in IVW, p = 0.007 in MR Egger), SSOE with asthma (p = 0.030 for IVW), and leisure-time television watching with COPD (p = 4.587E−04 for IVW; p = 0.001 for MR Egger). Despite this heterogeneity, the validity of the MR estimates was not undermined, given the high strength of the IVs and the application of the random-effect IVW model, both of which help mitigate heterogeneity concerns. Additional sensitivity analyses further reinforced the robustness of the findings, indicating that the observed heterogeneity did not compromise the reliability or interpretability of the results. Details on horizontal pleiotropy and heterogeneity, including their statistical tests, are presented in Supplementary Tables SVII–SXII, offering a more comprehensive overview of these sensitivity assessments.

Scatter plots (Supplementary Figures S1–S6) depict the effect sizes of associations between LSB and chronic respiratory diseases, as determined by various by MR methods. Leave-one-out analysis (Supplementary Figures S7–S12) showed the contribution of individual SNPs to the overall causality, revealing that no single SNP substantially drove the significant results. To assess the effect sizes of individual SNPs of LSB on chronic respiratory diseases, forest plots (Supplementary Figures S13–S18) provide detailed visualizations, allowing a closer examination of how each instrument contributes to the overall association. Moreover, funnel plots (Supplementary Figures S19–S24) under the IVW model appear symmetrical, suggesting minimal evidence of estimate violations and further reinforcing the reliability of these significant causal findings.

Discussion

Chronic respiratory diseases remain a significant global health concern, and conflicting observational evidence has complicated efforts to establish clear links between physical exercise and chronic respiratory illnesses [22, 23]. This study leveraged large-scale international consortium GWAS on PA and LSB to propose viable strategies for the prevention of chronic respiratory diseases. Specifically, we selected six common chronic respiratory diseases – namely asthma, bronchiectasis, COPD, IPF, PAH, and OSAS – from GBMI and FinnGen R10 datasets. Employing a two-sample MR approach, we identified eight statistically significant causal relationships that highlight the potential impact of lifestyle modifications.

PA and LSB appear to exert important but contrasting influences on asthma risk. Our research indicates that long-term television viewers are more likely to develop asthma, whereas SSOE and VPA can reduce the risk. This aligns with previous findings that reduced PA levels increase the likelihood of new-onset asthma among children and adolescents [40], and that increased PA can reduce the incidence of asthma [41]. Mechanistically, moderate increases in PA may offset obesity-related risk factors by alleviating airway compression and chronic inflammation [42]. Potential mediating pathways involve Th-1-mediated immune responses, alterations in adipokine levels, and activation of the pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome [43–45]. Although our results underscore the importance of reducing television watching time and increasing energy-consuming activities such as SSOE and VPA to alleviate obesity and lower asthma risk, the precise molecular underpinnings of these associations remain incompletely defined, calling for in-depth mechanistic research to elucidate the interplay between obesity, immune dysregulation, and lifestyle interventions.

Leisure-time television watching, a prevalent sedentary behavior [46], emerged in this study as a potential contributor to increased COPD susceptibility. This aligns with the known association between sedentary behavior and COPD-related mortality [47], potentially mediated by diminished muscle mass and strength – including respiratory muscles such as the diaphragm and intercostals. Prolonged television watching may also coincide with unhealthy lifestyle habits, such as smoking and alcohol consumption [48, 49], and tends to be more prevalent among individuals with lower socioeconomic status [50], which can exacerbate exposures to indoor air pollution and occupational hazards. Nonetheless, establishing a definitive causal chain linking LSB and COPD requires further investigation, ideally through longitudinal designs with objective measures of sedentary time and extensive confounding control.

For PAH, our research indicates that overall average acceleration may reduce susceptibility to PAH, aligning with research indicating that exercise enhances right ventricular mass and attenuates pulmonary vascular resistance [51, 52]. Intriguingly, our findings also suggest that prolonged leisure computer use may also exert a beneficial influence on PAH susceptibility, an observation that warrants caution in interpretation. Mechanistic plausibility may involve modifying vascular function and endothelial function [53], yet clear epidemiological evidence on this front is sparse. Further randomized controlled trials are crucial to clarify whether and how LSB might beneficially modulate cardiopulmonary physiology and the onset of PAH.

Our findings indicate that driving behaviors and VPA are inversely correlated with OSAS risk. Given the pivotal role of obesity in OSAS pathogenesis, sustained VPA may reduce fat accumulation in the pharyngeal area, lowering airway collapsibility during sleep [54, 55]. Furthermore, inflammation are critical components of OSAS-related diseases [56]. Regular training can enhance regulatory T cells levels and lower pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby reducing inflammation and potentially alleviating OSAS severity [57, 58]. The protective link between driving and OSAS, however, is less straightforward. It may be partially attributable to genetic variants such as rs476554, suggesting that this genetic variant, linked to driving, may reduce OSAS risk through an unknown mechanism. Larger genomic datasets incorporating detailed phenotypic assessments are needed to parse these unexpected associations more conclusively.

Consistent with prior research [25, 26, 32–34], our study reaffirms that leisure-time television watching increases the risk of asthma and COPD, whereas VPA appears to be protective against OSAS. Beyond these confirmatory results, we offer novel insights: SSOE and VPA were associated with reduced asthma risk, and overall average acceleration correlated inversely with PAH. Surprisingly, leisure-time computer use and driving activities – traditionally considered more sedentary – also displayed inverse associations with PAH and OSAS, respectively. Genetic variants associated with these behaviors may partly explain the unexpected findings, but the small number of SNPs analyzed highlights the need for greater statistical power and more nuanced phenotypic data.

Our investigation benefits from a two-sample MR analysis that substantially reduces residual confounding and reverse causality [27]. We drew upon large-scale GWAS studies with ample statistical power, and employed pleiotropy and sensitivity analyses to stringently evaluate violations of MR assumptions. Restricting our sample to European-ancestry participants also minimized bias due to population stratification. Additionally, the SNPs related to PA and LSB identified in our study have an F-statistic greater than 66, indicating strong instrumental validity.

Several limitations merit consideration. First, self-reported and accelerometer-based measurements of PA and LSB may not accurately represent the complexity of real-world activity patterns, raising concerns over reporting bias. Second, the relatively small number of SNPs for certain PA and LSB may have affected the precision of our MR estimates, especially concerning unexpected protective findings. Third, our reliance on aggregated data constrains the possibility of performing age- or sex-stratified analyses, nor does it allow for a precise quantification of the benefits of PA for different chronic respiratory diseases. Fourth, our dataset is confined to participants of European descent, limiting the generalizability of these findings. Caution is therefore warranted when extrapolating our findings to other populations.

In summary, this two-sample MR study investigated the causal relationship between PA, LSB, and chronic respiratory disorders from asthma and COPD to PAH and OSAS. However, MR estimates predominantly reflect the impact of lifetime exposure to risk factors, and the clinical relevance of modifying these behaviors at discrete life stages remains uncertain [59]. Additional randomized controlled trials are imperative to validate whether targeted interventions can effectively alter the trajectory of chronic respiratory diseases. By integrating mechanistic research, advanced genomic tools, and diverse populations, future studies may clarify how best to translate these findings into meaningful clinical interventions for chronic respiratory disease prevention and care.

In conclusion, utilizing existing GWAS databases to select robust genetic variants as IVs, this study employed a two-sample Mendelian randomization approach to elucidate the causal relationships between LSB and PA and chronic respiratory diseases. Our results suggest that strenuous sports or other exercises and vigorous PA are associated with a reduced risk of asthma, whereas leisure-time television watching correlates with an increased risk. Additionally, leisure-time television watching was positively correlated with the risk of developing COPD. Leisure-time computer use and overall average acceleration were inversely related to susceptibility to PAH. Driving and VPA were protective factors against OSAS. Our findings suggest new directions for understanding the impacts of PA and LSB on chronic respiratory diseases. Future randomized controlled trials could benefit from focusing more on these aspects to further validate and expand upon our results.