Current issue

Archive

Manuscripts accepted

About the Journal

Editorial office

Editorial board

Section Editors

Abstracting and indexing

Subscription

Contact

Ethical standards and procedures

Most read articles

Instructions for authors

Article Processing Charge (APC)

Regulations of paying article processing charge (APC)

HYPERTENSION / CLINICAL RESEARCH

Predicting hypertension in preeclampsia patients within five years postpartum: analysis of influencing factors and nomogram development

1

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing City, China

Submission date: 2025-05-29

Final revision date: 2025-07-25

Acceptance date: 2025-08-05

Online publication date: 2025-10-26

Corresponding author

Yanli Xu

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Beijing Ditan Hospital Capital Medical University Beijing City, China

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Beijing Ditan Hospital Capital Medical University Beijing City, China

KEYWORDS

TOPICS

ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-related hypertensive disorder with long-term cardiovascular risks. The aim of this study was to explore the factors influencing hypertension progression in preeclampsia patients within 5 years postpartum, and to construct a nomogram.

Material and methods:

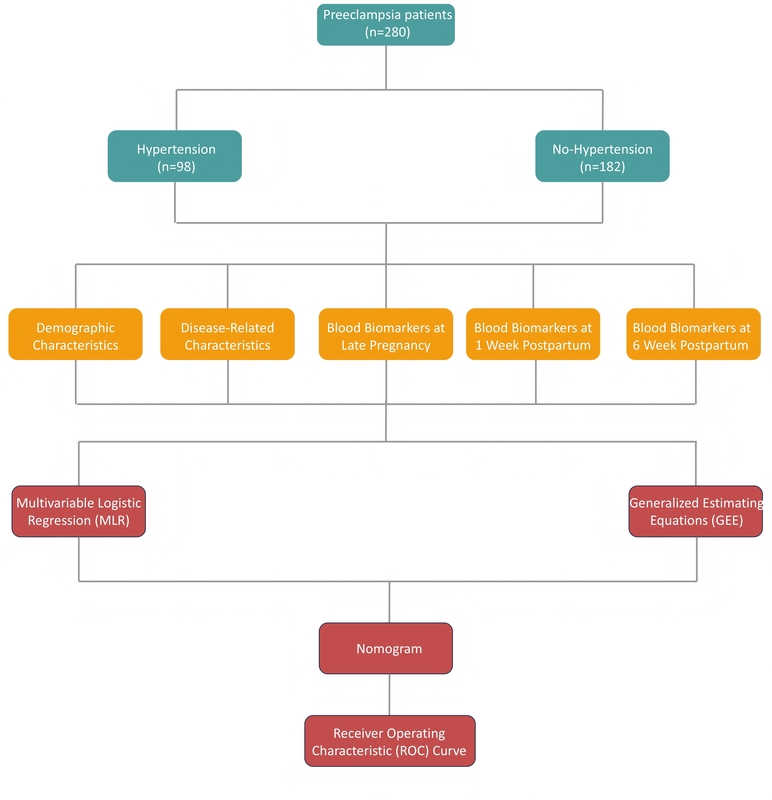

A retrospective study of 280 preeclampsia patients, grouped by hypertension progression status within 5 years postpartum, was performed. Differential analyses compared: 1) demographic/pregnancy characteristics, and 2) late-pregnancy, 1-week-postpartum, and 6-week-postpartum blood indicators between groups. Multiple logistic regression and generalized estimating equations (GEE) identified hypertension progression factors. Significant factors used to construct the nomogram were evaluated via calibration and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves in training/test sets.

Results:

Patients who progressed to hypertension had higher pre-pregnancy and postpartum body mass index (BMI), a greater proportion of early-onset and severe preeclampsia, and a higher incidence of adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to those who did not progress to hypertension. Additionally, they had lower platelet levels during late pregnancy and postpartum, while levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, 24-hour urinary protein, uric acid, and C-reactive protein were higher in patients who did not progress to hypertension. Multivariate logistic regression identified placental abruption, oligohydramnios, and umbilical artery pulsatility index as significant factors, while the generalized estimating equation highlighted uric acid (UA), platelet (PLT), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) as key predictors. The nomogram demonstrated good predictive performance, as shown by calibration and ROC curves.

Conclusions:

Hypertension progression correlates with placental abruption, oligohydramnios, elevated umbilical artery pulsatility index (UA-PI), elevated UA, decreased PLT, elevated ALT, and specifically aspartate aminotransferase at 1-week postpartum. The nomogram aids early identification of high-risk patients.

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-related hypertensive disorder with long-term cardiovascular risks. The aim of this study was to explore the factors influencing hypertension progression in preeclampsia patients within 5 years postpartum, and to construct a nomogram.

Material and methods:

A retrospective study of 280 preeclampsia patients, grouped by hypertension progression status within 5 years postpartum, was performed. Differential analyses compared: 1) demographic/pregnancy characteristics, and 2) late-pregnancy, 1-week-postpartum, and 6-week-postpartum blood indicators between groups. Multiple logistic regression and generalized estimating equations (GEE) identified hypertension progression factors. Significant factors used to construct the nomogram were evaluated via calibration and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves in training/test sets.

Results:

Patients who progressed to hypertension had higher pre-pregnancy and postpartum body mass index (BMI), a greater proportion of early-onset and severe preeclampsia, and a higher incidence of adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to those who did not progress to hypertension. Additionally, they had lower platelet levels during late pregnancy and postpartum, while levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, 24-hour urinary protein, uric acid, and C-reactive protein were higher in patients who did not progress to hypertension. Multivariate logistic regression identified placental abruption, oligohydramnios, and umbilical artery pulsatility index as significant factors, while the generalized estimating equation highlighted uric acid (UA), platelet (PLT), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) as key predictors. The nomogram demonstrated good predictive performance, as shown by calibration and ROC curves.

Conclusions:

Hypertension progression correlates with placental abruption, oligohydramnios, elevated umbilical artery pulsatility index (UA-PI), elevated UA, decreased PLT, elevated ALT, and specifically aspartate aminotransferase at 1-week postpartum. The nomogram aids early identification of high-risk patients.

REFERENCES (24)

1.

Rana S, Lemoine E, Granger JP, et al. Preeclampsia: pathophysiology, challenges, and perspectives. Circ Res 2019; 124: 1094-112.

2.

Roberts JM. Preeclampsia epidemiology(ies) and pathophysiology(ies). Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2024; 94: 102480.

3.

Opichka MA, Rappelt MW, Gutterman DD, et al. Vascular dysfunction in preeclampsia. Cells 2021; 10: 11.

4.

Dines V, Suvakov S, Kattah A, et al. Preeclampsia and the kidney: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Compr Physiol 2023; 13: 4231-67.

5.

Jung E, Romero R, Yeo L, et al. The etiology of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022; 226: S844-66.

6.

Yagel S, Cohen SM, Goldman-Wohl D. An integrated model of preeclampsia: a multifaceted syndrome of the maternal cardiovascular-placental-fetal array. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022; 226: S963-72.

7.

Ives CW, Sinkey R, Rajapreyar I, et al. Preeclampsia-pathophysiology and clinical presentations: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 76: 1690-702.

8.

Bokslag A, van Weissenbruch M, Mol BW, et al. Preeclampsia; short and long-term consequences for mother and neonate. Early Hum Dev 2016; 102. 47-50.

9.

Ma’ayeh M, Costantine MM. Prevention of preeclampsia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2020; 25: 101123.

10.

Almasi-Hashiani A, Omani-Samani R, Mohammadi M, et al. Assisted reproductive technology and the risk of preeclampsia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019; 19: 149.

11.

Gilboa I, Kupferminc M, Schwartz A, et al. The association between advanced maternal age and the manifestations of preeclampsia with severe features. J Clin Med 2023; 12: 20.

12.

Sibai BM. Etiology and management of postpartum hypertension-preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012; 206: 470-5.

13.

Hauspurg A, Jeyabalan A. Postpartum preeclampsia or eclampsia: defining its place and management among the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022; 226: S1211-21.

14.

Xue Q, Li G, Gao Y, et al. Analysis of postpartum hypertension in women with preeclampsia. J Hum Hypertens 2023; 37: 1063-9.

15.

Turbeville HR, Sasser JM. Preeclampsia beyond pregnancy: long-term consequences for mother and child. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2020; 318: F1315-26.

16.

Drost JT, Maas AH, van Eyck J, et al. Preeclampsia as a female-specific risk factor for chronic hypertension. Maturitas 2010; 67: 321-6.

17.

Roberge S, Bujold E, Nicolaides KH. Meta-analysis on the effect of aspirin use for prevention of preeclampsia on placental abruption and antepartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018; 218: 483-9.

18.

Bryan NS. Nitric oxide deficiency is a primary driver of hypertension. Biochem Pharmacol 2022; 206: 115325.

19.

Özgen G, Dincgez Cakmak B, Özgen L, et al. The role of oligohydramnios and fetal growth restriction in adverse pregnancy outcomes in preeclamptic patients. Ginekol Pol 2022; 93: 235-41.

20.

Duncan JR, Markel LE, Pressman K, et al. Comparison of umbilical artery pulsatility index reference ranges. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2025; 65: 71-7.

21.

Masoura S, Makedou K, Theodoridis T, et al. The involvement of uric acid in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rev 2015; 11: 110-5.

22.

Pishko AM, Levine LD, Cines DB. Thrombocytopenia in pregnancy: diagnosis and approach to management. Blood Rev 2020; 40: 100638.

23.

Gibson B, Hunter D, Neame PB, et al. Thrombocytopenia in preeclampsia and eclampsia. Semin Thromb Hemost 1982; 8: 234-47.

24.

Lee SM, Park JS, Han YJ, et al. Elevated alanine aminotransferase in early pregnancy and subsequent development of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. J Korean Med Sci 2020; 35: e198.

Share

RELATED ARTICLE

We process personal data collected when visiting the website. The function of obtaining information about users and their behavior is carried out by voluntarily entered information in forms and saving cookies in end devices. Data, including cookies, are used to provide services, improve the user experience and to analyze the traffic in accordance with the Privacy policy. Data are also collected and processed by Google Analytics tool (more).

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.