Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy, a potentially life-threatening condition characterized by the implantation of a fertilized ovum outside the uterine cavity, remains a significant concern in obstetrics [1].

Tubal pregnancies are the most common, but interstitial and cervical ectopic pregnancies can be more difficult to diagnose due to their atypical locations and symptoms overlapping with other conditions [2]. Abdominal ectopic pregnancies are rare and often diagnosed late, posing significant risks due to the potential for severe hemorrhage [3]. The variability in presentation and location of ectopic pregnancies necessitates a high degree of clinical suspicion and the use of advanced diagnostic tools to ensure accurate and timely identification [4].

Early diagnosis of heterotopic and cornual pregnancies through ultrasonography is crucial for optimal patient management. Heterotopic pregnancies, which involve simultaneous intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies, pose a significant diagnostic challenge and can be life-threatening if not identified promptly [5]. Use of advanced ultrasonography techniques, including point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), allows for early detection of these complex cases, enabling timely and appropriate clinical interventions that can prevent severe complications and improve patient outcomes.

Despite advances in diagnostic modalities, the timely and accurate diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy remains challenging, often leading to delays in treatment and increased morbidity [6]. In recent years, the advent of POCUS has revolutionized emergency medicine, offering rapid, bedside diagnostic capabilities [7]. POCUS, with its real-time imaging, provides an invaluable tool in the early detection of ectopic pregnancies, particularly in emergency settings where prompt diagnosis is crucial [8]. Its role in reducing time to diagnosis and subsequent treatment initiation is increasingly being recognized [8].

While both POCUS and traditional transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) are pivotal in diagnosing ectopic pregnancies, they differ significantly in terms of execution, accessibility, and application. Traditional TVUS, typically conducted by a radiologist or a specialized gynecologist, involves detailed imaging of the pelvic region and requires more sophisticated equipment and longer examination times [8, 9]. In contrast, POCUS can be performed at the bedside by emergency physicians or other trained healthcare providers, offering immediate, real-time imaging that facilitates rapid clinical decision-making (Table I).

Table I

Key differences between point-of-care ultrasound and traditional transvaginal ultrasound in gynecological diagnostics

Experienced operators and high-quality equipment generally yield lower false positive rates, while resource-limited settings and less experienced users may see higher rates. Thus, while POCUS is a valuable tool for rapid diagnosis, its accuracy can be affected by these variables, underscoring the importance of proper training and equipment quality [9, 10]. In POCUS diagnosis, handheld or portable ultrasound devices are typically used, differing from the stationary, high-resolution machines found in traditional ultrasound settings. Portable devices are designed for quick, bedside assessments and can be operated by various healthcare providers, while traditional devices require more advanced imaging capabilities and are often managed by specialists. These differences can affect results, as portable devices may have lower image resolution and limited functionality compared to their traditional counterparts, potentially impacting diagnostic accuracy, especially in complex cases [8–13].

Numerous studies have investigated the efficacy of POCUS in the emergency diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. A study by Stone et al. (2021) demonstrated the effectiveness of POCUS in reducing the time to treatment and operating room in emergency departments [14]. However, the literature is varied, with some studies presenting contrasting findings on the accuracy and reliability of POCUS in different clinical settings.

Early detection and treatment can prevent complications such as tubal rupture, which is associated with severe hemorrhage and can be life-threatening [15–17]. Moreover, the psychological impact on patients undergoing a suspected ectopic pregnancy cannot be understated. The anxiety and distress associated with prolonged diagnostic processes can be alleviated through the expedited clarity that POCUS provides [18, 19].

The significance of this study lies in its potential to inform clinical practice and policy-making in obstetrics and emergency medicine. By providing evidence-based insights, it aims to contribute to improving patient outcomes in ectopic pregnancy management, potentially guiding future research and clinical protocols. Hence, this study aims to synthesize existing literature to provide a clearer understanding of the impact of POCUS on the time to diagnosis and treatment in patients with ectopic pregnancy.

Material and methods

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: The review included the studies satisfying all the following characteristics:

Population: patients with ectopic pregnancy.

Intervention: POCUS at the emergency department.

Comparison: standard or usual ordered radiology department ultrasound.

Outcome: time to diagnosis (from the time of arrival at the hospital to the point of diagnosis), time to treatment (from the time of arrival at the hospital to the time of initiation of treatment) and time to operating room (from the time of arrival at the hospital to the time of arrival at the operating room).

Study design: Studies of all designs, i.e., randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies such as case-control, cohort, or cross-sectional studies) were considered.

Exclusion criteria: Studies were excluded if they did not provide sufficient data for the calculation of effect size or were published as abstracts only.

Search strategy

We conducted comprehensive searches in various electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. To enhance our search, we manually examined the reference lists of relevant reviews and studies that we included. In cases where additional unpublished data or clarifications were needed, we reached out to the authors of these studies. Our search focused on terms related to “ectopic pregnancy”, “point of care ultrasound”, and “emergency department”, using both medical subject headings (MeSH) and corresponding keywords suitable for each specific database. Our search strategy did not impose any restrictions regarding the language of publication or the date of publication.

Study selection process

The initial screening of titles and abstracts from the collected studies was carried out independently by two reviewers. Following this, they acquired and thoroughly assessed the full texts of studies that appeared to meet the eligibility criteria. In instances of disagreement between the reviewers, they resolved these through discussion, or by consulting a third reviewer when necessary.

Data collection process

For the process of data collection, two reviewers extracted information separately using a pre-defined data extraction template. This included extracting details such as the study’s author, the journal, the year of the study and its publication, and the study design. Additionally, they gathered data on the characteristics of the participants, such as the total sample size and sample sizes in each study group, the average or median age, the distribution of genders, and whether the ectopic pregnancies were ruptured or unruptured. Further data on the specifics of the POCUS and its comparator group, the time taken for diagnosis, treatment, or transfer to the operating room, and information vital for evaluating the risk of bias were also collected. Finally, any data regarding the funding sources for the studies and any potential conflicts of interest were noted.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Two investigators took on the task of evaluating the quality of the studies included. They used the Newcastle Ottawa scale (NOS) for observational studies [20], which includes three criteria: selection of study groups (rated from 0 to 4 stars), comparability of the groups (0–2 stars), and the determination of exposure or outcome (0–3 stars). Studies scoring seven stars or more were deemed high quality. The researchers resolved any differences in opinion through discussion to reach a consensus. In cases where a consensus was not possible, a third opinion was sought for a decision.

Data synthesis

The meta-analysis was performed to pool the data across the studies. A random-effects model with the inverse variance method was used to account for heterogeneity [21]. The mean, standard deviation (SD), and sample size were entered for patients in both groups. The measure of effect used for interpretation was the standardized mean difference (SMD), as all the outcomes are continuous. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the χ2 test and I2 statistic. However, these are relative measures of heterogeneity, and hence the prediction interval was reported along with the confidence interval for the pooled estimate. This interval provides a range in which the true effect size for individual settings or populations is expected to fall, considering the heterogeneity among the studies.

Subgroup analyses were performed based on the rupture status of ectopic pregnancies. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the results. A Doi plot and the Luis Furuya-Kanamori (LFK) index were used to check the publication bias for all the outcomes [22]. The Doi plot visualizes asymmetry in meta-analyses, while the LFK index quantifies this asymmetry. A high LFK index may indicate potential publication bias. We also checked for selective reporting within studies by comparing the reported outcomes with those listed in the study protocols or trial registries.

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the quality of the evidence for each outcome [23]. GRADE is a systematic approach to grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations. It considers several factors: risk of bias – evaluates the reliability of the study design; consistency – looks for similarity in the study results; directness – assesses the direct application of the study results to the research question; precision – examines the certainty or the degree of variability in the effect estimates [24]; publication bias – identifies the likelihood of selective publication of studies.

This entire review and analysis was done in accordance with the PRISMA checklist [25].

Results

Search results

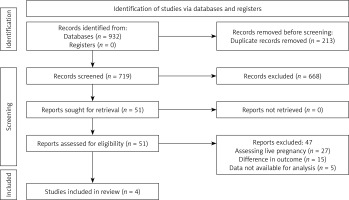

Overall, after searching all the databases, 932 studies were obtained, and they underwent duplicate removal. Then, primary screening of titles and abstracts was conducted, and 51 full texts were retrieved. After screening these full texts with eligibility criteria, four studies satisfied all the criteria and were included in the review and meta-analysis (Figure 1) [14, 26–28].

Characteristics of the included studies

Table II presents the characteristics of the included studies. All the studies were conducted in the United States of America and were retrospective reviews of records. Sample size ranged from 10 to 38 in the POCUS group and 21 to 73 in the control group. Two studies were conducted exclusively amongst ruptured ectopic pregnancy patients. Mean age of the patients ranged from 28.6 to 31.2 years. All the studies (except Stone 2021 – low risk of bias) [10] had a moderate risk of bias (Table III).

Table II

Characteristics of the studies included (N = 4)

Table III

Quality assessment of the included studies (N = 4)

Impact of POCUS on time to diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in emergency setting

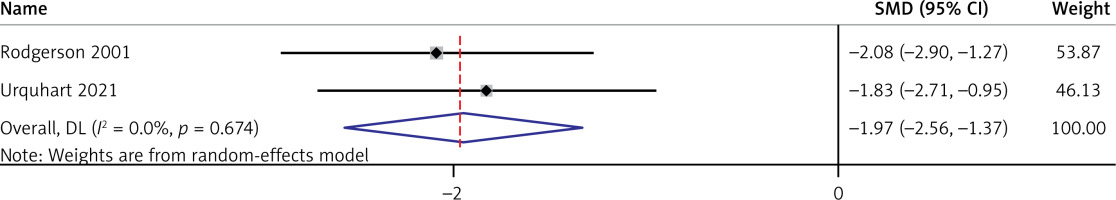

In this meta-analysis of two studies with a total of 69 participants, the pooled SMD using the random-effects inverse-variance model was –1.965 (95% CI: –2.562 to –1.368), indicating a significant overall effect (z = –6.453, p < 0.001) (Figure 2). The heterogeneity was negligible, with an I2 of 0.0% (Cochran’s Q = 0.18, p = 0.674), suggesting consistency among the included studies. These results demonstrate a substantial and uniform effect of reduction in time to diagnosis due to use of POCUS in an emergency setting across the studies analyzed. Additional subgroup analysis, prediction interval estimation, sensitivity analysis and publication bias assessment could not be performed for this outcome due to inclusion of only two studies for analysis.

Impact of POCUS on time to treatment of ectopic pregnancy in an emergency setting

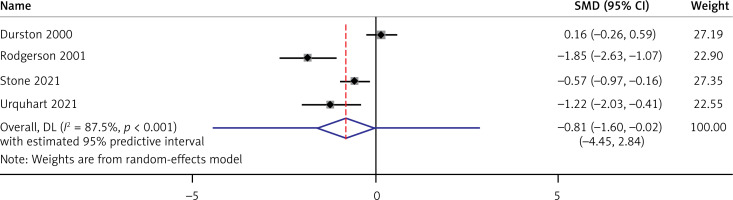

Four studies with a total of 266 participants studied the impact of POCUS on time to treatment of ectopic pregnancy in an emergency setting. The pooled SMD was –0.809 (95% CI: –1.602 to –0.017), indicating a modest overall effect (z = –2.002, p = 0.045) (Figure 3). However, there was significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 87.5%, Cochran’s Q = 24.08, p < 0.001), suggesting substantial variability in the effect sizes across studies.

Figure 3

Forest plot showing the impact of point-of-care ultrasound on time to treatment of ectopic pregnancy

The prediction interval ranged from –4.45 to 2.84, highlighting a wide range of possible true effects.

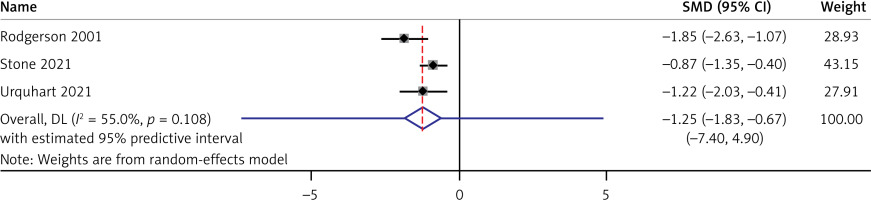

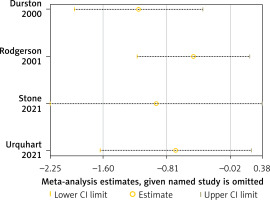

Subgroup analysis was made to evaluate the impact of POCUS on time to treatment of ruptured ectopic pregnancy patients alone. Three studies have reported estimates separately for ruptured ectopic pregnancy. The pooled SMD was –1.252 (95% CI: –1.834 to –0.669), with a significant overall effect (p < 0.001) (Figure 4). The Doi plot (Figure 5) showed a major asymmetry, which was further confirmed by an LFK index of –2.12. This indicates the presence of publication bias. However, leave-one-out sensitivity analysis revealed that the study estimates are robust and credible (Figure 6).

Impact of POCUS on time to operating room for surgically treating the ectopic pregnancy in an emergency setting

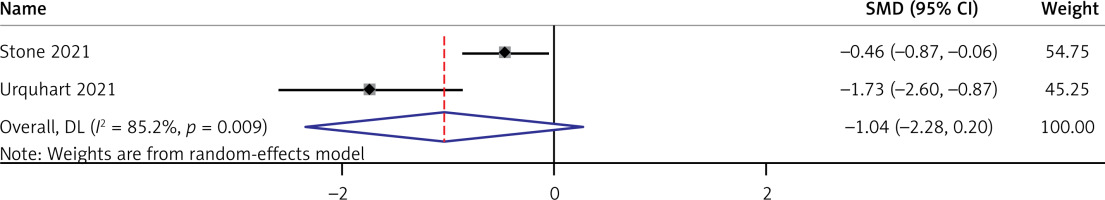

Two studies with 141 participants reported the impact of POCUS on time to operating room for surgically treating the ectopic pregnancy in an emergency setting. The pooled SMD was –1.038, but this did not reach statistical significance (95% CI: –2.276 to 0.200, z = –1.644, p = 0.100) (Figure 7). Considerable heterogeneity was observed between the studies (I2 = 85.2%, Cochran’s Q = 6.77, p = 0.009), indicating notable variation in the effect size between the included studies.

Figure 7

Forest plot showing the impact of point-of-care ultrasound on time to operating room for treating ectopic pregnancy

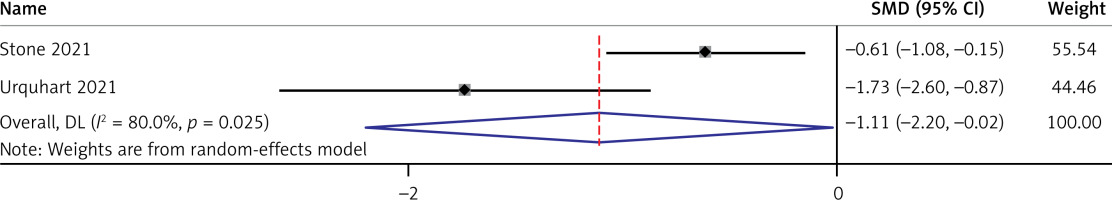

Separate analysis including only ruptured ectopic pregnancy patients revealed that the pooled SMD was –1.110 (95% CI: –2.203 to –0.017), with a significant overall effect of p = 0.046 (Figure 8). This indicates that the POCUS is beneficial in terms of time to operating room for at least ruptured ectopic pregnancy patients. Additional prediction interval estimation, sensitivity analysis, and publication bias assessment could not be performed for this outcome due to inclusion of only two studies for analysis.

Figure 8

Forest plot showing the impact of point-of-care ultrasound on time to operating for treating ruptured ectopic pregnancy

As per GRADE evidence profile, the risk of bias was moderate, there was no indirectness (as a separate analysis based on ruptured ectopic pregnancy was performed); however, imprecision was present as the CI of SMD crossed 0.5 on either side of the CI for all the outcomes, moderate to high heterogeneity was found across almost all the outcomes, and publication bias was present for the only outcome assessed, indicating that the overall quality of evidence is very low.

GRADE evidence

According to the GRADE evidence profile, the risk of bias was deemed moderate. There was no evidence of indirectness, as analyses were appropriately stratified based on ruptured ectopic pregnancies. However, the quality of evidence was compromised by imprecision, as indicated by the confidence intervals of the SMD extending beyond 0.5 on either side for all outcomes. Additionally, moderate to high heterogeneity was observed across nearly all outcomes. Publication bias was also detected in the one outcome where it was assessed. Collectively, these factors lead to the conclusion that the overall quality of evidence is very low.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis presents significant insights into the use of POCUS in the diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy in emergency settings. The analysis across various outcomes reveals a complex picture. The use of POCUS significantly reduced the time to diagnosis of ectopic pregnancies, with a pooled SMD of –1.965.

A modest but significant effect on time to treatment was observed (pooled SMD of –0.809). The notable heterogeneity (I2 = 87.5%) in these results suggests variability in implementation or effectiveness across different settings. For the overall cohort, the reduction in time to operating room was not statistically significant. However, in the subgroup of ruptured ectopic pregnancies, a significant reduction was noted. This indicates that POCUS may particularly benefit patients with more severe presentations.

Previous studies have also highlighted the utility of POCUS in emergency settings, especially for conditions requiring rapid decision-making [11–13, 29, 30]. Our findings align with these studies but go a step further by quantifying the impact specifically for ectopic pregnancies [29, 30]. The immediacy of POCUS likely contributes to quicker decision-making, bypassing the usual delays associated with standard radiology department scans. The emphasis of this study on the specific application of POCUS for ectopic pregnancies in emergency settings is a critical addition to the existing body of literature. Historically, the integration of ultrasound technology in emergency medicine has been a transformative development. Prior research predominantly focused on the utility of ultrasound for a range of urgent conditions, but our study provides a targeted analysis of its effectiveness specifically for ectopic pregnancy [31]. This specificity offers valuable insights into the nuanced application of ultrasound technology in emergency gynecological care, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of its role in different emergency scenarios.

The observed variability in the effectiveness of POCUS can be attributed to several factors. First, the emergency department workflow variations, i.e., differences in the protocols, staffing, and resources of emergency departments, can significantly impact the efficiency of ultrasound use [32]. In environments where staff are trained and protocols are optimized for ultrasound use, the time to diagnosis and treatment can be notably reduced. Second, the operator expertise, i.e., the skill level and experience of the ultrasound operator, plays a crucial role. Studies have shown that operator proficiency can significantly influence diagnostic accuracy and efficiency, impacting patient outcomes [33]. Finally, the patient demographics and presentation, i.e., factors such as the patient’s age, medical history, and severity at presentation, might also influence the effectiveness of POCUS [14, 34]. For instance, in more acute presentations such as ruptured ectopic pregnancies, the rapid diagnosis afforded by ultrasound can be particularly beneficial.

This review has certain strengths. Our study provides a comprehensive analysis across multiple relevant outcomes. The inclusion of both overall and subgroup analyses offers a nuanced view of the utility of POCUS in varying clinical scenarios. We have also reported the prediction interval, publication bias assessment and sensitivity analysis, wherever possible. However, the study has certain limitations. The presence of heterogeneity and publication bias, particularly in the time to treatment analysis, warrants caution in interpreting these findings. The limited number of studies included, especially for certain outcomes, restricts the generalizability of our conclusions. Small sample sizes in the included studies limit generalizability, and hence, future studies should aim for larger, multi-center trials.

While integrating POCUS into emergency protocols may entail additional costs, these should be weighed against the potential benefits of reduced time to diagnosis and treatment, which can lead to improved patient outcomes and potentially lower overall healthcare costs. The results support the need for cross-disciplinary collaboration, ensuring that obstetrics teams are promptly informed and involved in cases of ectopic pregnancy identified in the emergency department.

The findings of this study have significant clinical implications, particularly for the management of ectopic pregnancies in emergency settings. The demonstrated reduction in time to diagnosis and initiation of treatment with the use of POCUS underscores its potential to improve patient outcomes by facilitating timely clinical decisions and interventions. This study contributes to the existing literature by providing a quantified analysis of the benefits of POCUS, particularly highlighting its efficacy in reducing diagnostic and treatment delays. These insights support the integration of POCUS into standard emergency department protocols for suspected ectopic pregnancies. Future studies should focus on optimizing POCUS training programs for emergency physicians, exploring long-term patient outcomes, and addressing the identified heterogeneity to further refine its application in clinical practice. Future studies should also aim to address the heterogeneity observed in our findings through larger, more standardized studies. Future studies should also explore the impact of operator skill and experience on the effectiveness of POCUS.

The main findings of this study highlight the substantial benefit of POCUS in reducing both diagnostic and treatment delays for patients with ectopic pregnancy. By significantly shortening the time to diagnosis and initiation of treatment, POCUS not only improves clinical outcomes but also alleviates the psychological burden on patients. These benefits emphasize the need for widespread adoption of POCUS in emergency settings, reinforcing its value as a rapid, reliable, and non-invasive diagnostic tool. While the findings indicate potential improvements in time to treatment and operating room readiness, especially in more severe cases, the quality of evidence and heterogeneity suggest a need for cautious interpretation.