Multiple forms of cell death may occur in response to various environmental stresses, particularly oxidative stress. Loss of control of cell death (in various forms) causes many human diseases such as cancer, autoimmune diseases, neurodegeneration, and infectious diseases [1]. Classically, cell death is categorized into regulated cell death (RCD), known as apoptosis, and premature cell death, which is known as necrosis. In recent studies, a growing number of non-apoptotic modes of RCD have been discovered. These include pyroptosis, autophagy, NETosis, and ferroptosis. According to the recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death (NCCD) 2018, pyroptosis is a regulated form of cell death characterized by the generation of membrane pores mediated by the gasdermin (GSDM) protein family, often but not always as a consequence of the activation of inflammatory caspases [2]. It seems that pyroptosis shares morphological properties with both apoptotic and necrotic cell death. The plasma membranes of pyroptotic cells swell and rupture, and DNA fragmentation occurs (as demonstrated by positive TUNEL staining), similarly to apoptosis. However, mitochondrial integrity is preserved, and cytochrome c is not released [3]. Pyroptosis can be distinguished from apoptotic pathways of cell death by several features including the release of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukins IL-1β and IL-18. Pyroptosis can be induced by caspase-1 and caspase-4/-5 in humans, whereas classical apoptotic caspases are not involved. Despite the occurrence of nuclear fragmentation in pyroptosis, this is not as prominent as that detected in apoptosis [4].

Caspases are essential for initiating apoptosis and pyroptosis. Caspase-1 is one of several inflammatory caspases that play important roles in the innate immune response. There are 2 distinct pathways for pyroptosis. These are triggered by different caspases. Caspase-1 is activated by the canonical inflammasomes, and caspase-11 (human caspase-4/-5) is activated by non-canonical inflammasomes [3]. In both pathways, inflammasomes are primed and the expression of pro-IL1β and pro-IL18 levels is enhanced via activation of pattern-recognition receptors (PRR) [4]. Inflammasomes are cytoplasmic protein complexes, which form families of PRRs (such as the subfamily of NOD-like receptors (NLRs)), inflammatory caspases, and in some cases an adaptor protein. They can be activated by endogenous and exogenous stimuli acting as a molecular signal platform for enzymatic activation of caspases and the subsequent inflammatory response [2]. The subsequent mechanisms differ between the 2 pathways. In the canonical pathway, activated caspase-1 catalyses the maturation of cytokines pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their active forms, which results in pyroptosis. However, activated caspase-11 triggers pyroptosis directly in the noncanonical pathway. Activated caspase-1 is indirectly required for the production of IL-1β and IL-18 in the noncanonical pathway [4]. It has been demonstrated that cell rupture and the release of proinflammatory mediators in the extracellular space amplifies the inflammatory response and exacerbates the injury caused by initiation of the cascade. Activation of caspases occurs in response to a variety of stimuli, which are identified by distinct inflammasomes. The key factors contributing to the activation of the NLRP3 (NLR family pyrin domain containing 3) inflammasome (the most extensively studied inflammasome) include reactive oxygen species, lysosomal membrane disruption, and ion efflux (including Ca2+ mobilization and K+ efflux). In addition, microRNAs (miRNAs) have recently been shown as a key regulator of the NLRP3 inflammasome [2].

Appropriate inflammatory responses and the induction of pyroptosis enhance the clearance of pathogens and increase innate immunity. However, excessive pyroptosis contributes to a hyperinflammatory response and aggravates tissue damage, thereby causing inflammatory diseases. A great deal of evidence shows that some drugs or compounds that inhibit pyroptosis may be effective for the treatment of various inflammatory diseases. In this regard, it is tempting to speculate that statins could be good candidates. The efficacy of statins is well established in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. They reduce circulating concentrations of cholesterol by inhibiting 3-hydroxy-3- methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme of the mevalonate pathway of cholesterol synthesis. In addition to their well-documented lipid-lowering effects, there is a widely held view that statins exert many pleiotropic effects including anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant, and immune-modulatory effects [5–9]. Moreover, many studies have demonstrated the anticarcinogenic effect of statins in several models, including carcinoma of the prostate, colon and rectum, liver, lung, breast, and skin. There is evidence that statins are associated with cell death and apoptosis [4, 10]. However, the mechanisms that mediate these effects remain poorly understood but may involve reductions of downstream products of the mevalonate pathway including dolichols, isoprenoid intermediates, heme A, and coenzyme Q10 [11].

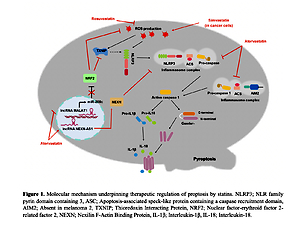

Recent studies provide evidence for the potential value of statins in targeting pyroptosis in various diseases. For example, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and myocardial pyroptosis induced cardiac injury following coronary microembolization (CME). Chen et al. revealed an anti-pyroptotic role of rosuvastatin in CME-induced cardiac dysfunction mediated via reduction of mitochondrial damage and ROS production. Rosuvastatin exerted an inhibitory effect on the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway and suppressed the expression of cleaved-caspase-1, IL-1β, and GSDMD-N [12]. It was found that targeting of the inflammasome was a promising approach for the management of ulcerative colitis. Rosuvastatin treatment effectively reduced Ox-LDL-induced TXNIP (thioredoxin interacting protein) and thus attenuated the inflammatory response via NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition [13]. Wang et al. reported that atorvastatin inhibited pyroptosis in vascular endothelial cells (ECs) by upregulation of the long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) NEXN-AS1 and its neighbouring gene NEXN. Expression of NEXN-AS1 has been shown to be reduced in human atherosclerotic plaques. Both mRNA and protein expression levels of canonical inflammasome pathway biomarkers including caspase-1, IL-1β, IL-18, and NLRP3 were decreased by atorvastatin, which then decreased inflammation and the progression of atherosclerosis [10]. Metastasis-related lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) is another lncRNA that has been shown to be associated with pyroptosis. Upregulation of MALAT1 evidently attenuated H2O2-induced pyroptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, causing NRF2 (nuclear factor-erythroid factor 2-related factor 2) stabilization and activation. Atorvastatin was found to decrease renal oxidative stress and podocyte pyroptosis under conditions of high glucose. This occurred via the MALAT1/miR-200c/ NRF2 axis [14]. Atorvastatin has also been reported to improve early brain injury (EBI) after subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) by inhibition of neural pyroptosis and neuroinflammation through the ASC/AIM2 inflammatory pathway [15]. In addition to the beneficial effects of statins on cardiovascular health, their anticancer properties have recently received increasing interest. There is some evidence that using statins improved survival in patients with lung cancer whether used before or after diagnosis. It was demonstrated that simvastatin induced pyroptosis in a xenograft mouse model and in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines. Thus, simvastatin treatment attenuated the viability and migration of tumour cells without causing toxicity to normal lung cells [4]. In conclusion, pharmacological activation of pyroptosis in cancer is beneficial, whereas inhibition of pyroptosis in inflammatory conditions can ameliorate disease. The most recent literature describes putative roles for statins in the regulation of pyroptosis. As shown in Figure 1, statins can contribute to inhibition of pyroptosis via the canonical inflammasome pathway. In addition, it seems that interference with oxidative stress is the prominent mechanism of the regulation of pyroptosis by statins. These findings have important implications for the development of new treatment strategies in a range of diseases.

Figure 1

Molecular mechanism underpinning therapeutic regulation of pyroptosis by statins

NLRP3 – NLR family pyrin domain containing 3, ASC – apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain, AIM2 – absent in melanoma 2, TXNIP – thioredoxin interacting protein, NRF2 – nuclear factor-erythroid factor 2-related factor 2, NEXN – nexilin F-actin binding protein, IL-1β – interleukin-1β, IL-18 – interleukin-18.

Conflict of interest

Peter E. Penson owns 4 shares in AstraZeneca PLC and has received honoraria and/or travel reimbursement for events sponsored by AKCEA, Amgen, AMRYT, Link Medical, Mylan, Napp, Sanofi; G.B. Maciej Banach: speakers bureau: Amgen, Herbapol, Kogen, KRKA, Polpharma, Mylan/Viatris, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva, Zentiva; consultant to Abbott Vascular, Amgen, Daichii Sankyo, Esperion, FreiaPharmaceuticals, Novartis, Polfarmex, Sanofi-Aventis; Grants from Amgen, Mylan/Viatris, Sanofi, and Valeant; all other authors have no conflict of interest.