Introduction

Coffee stands as one of the world’s most widely consumed beverages, valued not only for its ability to enhance alertness and cognitive performance but also for its potential health benefits [1]. Accumulating evidence from large-scale epidemiological studies supports an inverse association between moderate coffee consumption and the risk of several chronic diseases: type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer, and all-cause mortality. For instance, a major European cohort study (> 460,000 participants) reported that 3 cups of coffee per day was associated with a 12% reduction in all-cause mortality, a 17% decrease in CVD mortality, a 21% lower risk of stroke [2], and a 6% reduced risk of T2DM [3]. Consequently, these findings have led most prominent health authorities to endorse moderate coffee intake as part of a healthy diet [4–6].

Central to these benefits may be the effect of coffee on insulin resistance (IR), which is considered as a decrease in sensitivity or responsiveness to the metabolic actions of insulin including insulin-mediated glucose disposal, a key pathophysiological mechanism underlying a spectrum of metabolic disorders including T2DM, CVD [7, 8], and metabolic syndrome [9]. Improving insulin sensitivity represents a promising strategy for mitigating multiple metabolic diseases simultaneously [10, 11], and its health behaviours include single or combined modalities such as regular exercise, dietary modification, and changes in bad habits [12–14].

Although early 20th-century research first identified that coffee consumption could enhance insulin sensitivity [15], subsequent evidence remains inconsistent. Meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) [16] have shown short-term improvements in IR measures such as Homeostasis Model Assessment of IR (HOMA-IR), but these effects often lack sustainability in longer-term or sensitivity analyses. Intriguingly, a recent analysis of 7453 participants from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [17] revealed that women consuming ≥ 2 cups of black coffee (without additives) daily exhibited a 27% lower IR index and a 30% reduction in fasting hyperinsulinaemia. Those consuming ≥ 3 cups daily experienced nearly 40% lower IR risk and approximately 50% reduced risk of elevated fasting insulin. Notably, these benefits were absent in men and were negated when sugar or creamer was added. While this study quantified intake, it did not explore the impact of consumption timing. Although other research associates coffee consumption timing (morning vs. later in the day) with reduced all-cause and CVD mortality risk, its specific effect on IR remains unelucidated [18].

In summary, despite evidence linking coffee intake quantity and timing to mortality risk [9], consistent data on the effects of coffee dosage, timing, and their interaction on IR, the cornerstone of metabolic diseases, are lacking. This study utilises nationally representative US data to evaluate the impact of coffee consumption patterns (defined by timing and dose, based on prior cluster analysis) on IR, aiming to identify potentially healthier intake patterns.

Material and methods

Study design

This cross-sectional study utilised data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database. NHANES, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is designed to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States [19]. All NHANES participants provided written informed consent, and the dataset is de-identified to ensure participant anonymity.

Study population

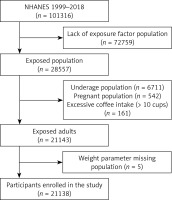

We extracted data on demographics, laboratory measurements, coffee intake, and comorbidities from the NHANES cycles spanning 1999 to 2018. Participants were included if they met the following criteria: (1) aged ≥ 20 years; (2) had complete coffee intake data; and (3) had available laboratory measures required for estimating IR. Initially, 21,846 individuals met these criteria. We further excluded participants who were pregnant (n = 542), had missing sample weight data (n = 5), or reported implausibly high coffee intake (> 10 cups/day, n = 161). This resulted in a final analytical sample of 21,138 participants.

Assessment of coffee intake

Coffee intake data were obtained from the 24-hour dietary recall interviews within the NHANES Dietary Data component. During 1999-2002, each participant underwent a single in-person interview at a Mobile Examination Centre. From 2003 to 2017, participants completed an initial in-person interview followed by a second telephone interview 3–10 days later. To minimise potential systematic errors introduced by repeated recalls, this study exclusively utilised data from the first in-person dietary recall interview. Dietary records were identified to quantify the keyword “coffee” to extract coffee consumption. Daily coffee intake was calculated in cups (a standard cup is 8 ounces, 237 ml, or 226.4 g [13]). Participants were categorised into 5 intake groups: non-consumers, Q1 (≤ 1 cup/day), Q2 (1–2 cups/day), Q3 (2–3 cups/day), and Q4 (> 3 cups/day). To account for potential confounding by circadian rhythms on insulin sensitivity, and consistent with prior methodology [13], intake timing patterns were classified as: “Morning-only intake” (consumption solely between 4:00 AM – 11:59 AM) and “All-day intake” (consumption occurring across multiple time periods). Additional analyses considered coffee type (caffeinated vs. decaffeinated) and the addition of sugar.

Assessment of insulin sensitivity

Insulin sensitivity was estimated using the validated estimated glucose disposal rate (eGDR), a surrogate for the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp technique, the gold standard for assessing insulin sensitivity [20]. In this study, we employed the eGDR as a validated surrogate marker. The eGDR was calculated using body mass index and 4 serum biochemical parameters (Additional file 1). This index has been previously validated and is widely used in epidemiological studies [21–23]. Higher eGDR values indicate greater insulin sensitivity. Participants were dichotomised into insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant groups based on the median eGDR value for subsequent analyses.

Covariates

Covariates encompassed demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, and health status. Demographic variables included the following: age (categorised as < 45, 45–65, or ≥ 65 years), sex, race/ethnicity (Mexican American, Other Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Other [including Asian]), marital status (never married, married, or cohabiting), education level (less than college, college graduate, or above), and family income-to-poverty ratio (PIR; categorised as < 1.3, 1.3–3.5, or ≥ 3.5). Lifestyle factors comprised smoking status (current/former smoker vs. never smoker) and alcohol consumption status (current drinker vs. non-drinker). Health status variables included self-reported physician diagnoses (or medication use) for hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and coronary heart disease, ascertained via standardised NHANES questionnaires. All covariate data were collected through NHANES questionnaires and physical examinations, incorporating all survey cycles to ensure comprehensiveness and national representativeness.

Statistical analysis

Analyses accounted for the complex, multi-stage probability sampling design of NHANES by incorporating appropriate sample weights, strata, and primary sampling units, as per NHANES analytical guidelines. Categorical variables are presented as unweighted counts (n) and weighted percentages (%). Group comparisons employed Rao-Scott χ2 tests, which adjust for the survey design. The association between coffee intake patterns and insulin sensitivity (dichotomised outcome) was assessed using multivariable binary logistic regression. Three sequential models were constructed: Model 1 adjusted for age only; Model 2 additionally adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, and PIR; and Model 3 further adjusted for hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Dose-response relationships between coffee intake (continuous, cups/day) and eGDR (continuous) were explored using restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression with 4 knots; knot positions were optimally selected based on ANOVA F-tests. Interaction effects between key covariates and the primary exposure (coffee intake pattern/dose) on the outcome were tested using multiplicative interaction terms in the logistic regression models. Stratified analyses were performed to illustrate subgroup-specific effects. Sensitivity analyses examined the influence of coffee type (caffeinated/decaffeinated) and the addition of sugar. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value < 0.05. This study adhered to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for reporting observational research [24].

Results

Baseline characteristics according to coffee intake patterns

The analytical cohort comprised 21,138 participants, representing an estimated 88,936,387 US adults. The selection process is summarised as a flowchart shown in Figure 1. Non-consumers of coffee constituted 46.79% of the weighted sample. Among coffee consumers (53.21%), 76% reported predominantly morning intake. Participants with morning-only intake were most frequently in the Q2 consumption category (1–2 cups/day), while those with all-day intake were most often in the Q4 category (> 3 cups/day). Younger adults (< 45 years) were more likely to be non-consumers, low consumers (Q1), or morning-only consumers. Conversely, older adults (≥ 65 years) exhibited higher consumption levels (Q3–Q4) and were more likely to follow an all-day intake pattern. Higher educational attainment, higher income, and being married or cohabiting were associated with greater coffee consumption and a higher prevalence of all-day intake patterns. Similarly, current or former smokers and current alcohol drinkers consumed more coffee and were more likely to adopt an all-day intake pattern. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table I.

Table I

Weighted baseline sociodemographic characteristics among included NHANES participants, 1999–2018

Association between coffee intake patterns and IR

Logistic regression analyses are presented in Table II. Morning coffee consumption in the lowest quartile (Q1: ≤ 1 cup/day) was significantly associated with improved insulin sensitivity (reduced IR) in the minimally adjusted model (Model 1: odds ratio [OR] = 1.37, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.16–1.62). However, this beneficial association attenuated with increasing intake quantity (p < 0.05). In the all-day intake pattern, coffee consumption showed a non-significant trend towards improved insulin sensitivity (Model 1: OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 0.83–1.73). Notably, within the all-day pattern, higher consumption levels (Q3: OR = 1.46, 95% CI: 1.13–1.89; Q4: OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.11–1.63) were significantly more beneficial than lower intake (Q1–Q2). Adjustment for broader sets of covariates (Models 2 and 3) yielded similar effect sizes and trends for improved insulin sensitivity associated with coffee intake in both morning and all-day patterns. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of these findings (Supplementary Table SI).

Table II

Associations between coffee intake levels and GDR under different drinking patterns

Dose-response relationships and optimised intake patterns

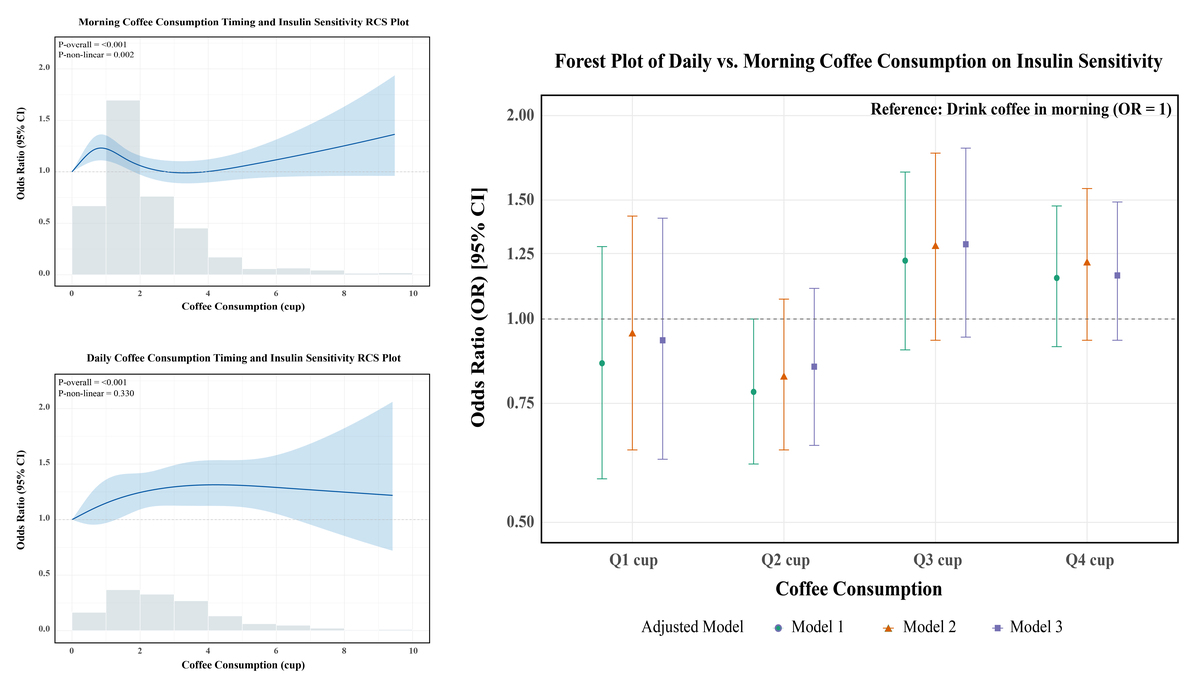

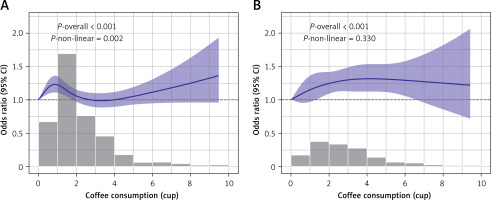

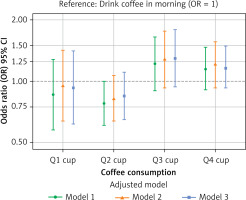

RCS analysis revealed a significant non-linear dose-response relationship between morning coffee intake and IR (p-nonlinear = 0.002; Figure 2 A). Morning intake showed an initial improvement in insulin sensitivity at lower doses, which diminished around 3 cups/day, followed by a potential resurgence of benefit at very high intakes. In contrast, the all-day intake pattern demonstrated a significant positive linear dose-response relationship (p-overall < 0.001, p-nonlinear = 0.330; Figure 2 B), indicating progressively greater benefit with higher intake. To directly compare the effects of intake timing at specific doses, multivariate logistic regression (Model 3) was used (Table III). For low-to-moderate intake (Q1–Q2: ≤ 2 cups/day), morning consumption showed a non-significant trend towards greater benefit compared to all-day consumption (Q1: OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.62–1.41; Q2: OR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.65–1.11). Conversely, for higher intake levels (Q3–Q4: > 2 cups/day), all-day consumption showed a non-significant trend towards greater benefit (Q3: OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 0.94–1.79; Q4: OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.90–1.49). These results suggest a complex interaction between dose and timing, supporting the recommendation of morning consumption for lower amounts (≤ 2 cups/day) and distributing higher amounts (> 2 cups/day) throughout the day for optimal effects on insulin sensitivity (Figure 3, Table III).

Figure 2

RCS analysis in different drinking patterns. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) curves showing the association between coffee intake and the odds of low GDR, stratified by drinking pattern. A – Morning-only coffee drinkers. B – All-day coffee drinkers

Figure 3

Forest plot of the associations between coffee drinking patterns and GDR levels, stratified by intake levels

Table III

Associations between coffee drinking patterns and GDR under different intake levels

Influence of coffee type, additives, and subgroup analyses

Analyses adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical confounders revealed that caffeinated coffee intake was significantly associated with higher eGDR (Supplementary Table SII). For morning intake, the association was strongest at Q1 (OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.16–1.66) and attenuated with increasing dose (Q4: OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.98–1.37). For all-day intake, significant benefits were observed at higher doses (Q3: OR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.10–1.87; Q4: OR = 1.35, 95% CI: 1.11–1.64). Decaffeinated coffee showed a significant association only at Q2 (OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.05–1.78). Unsweetened coffee consumed throughout the day was associated with higher eGDR at Q3–Q4 (Q3: OR= 1.40, 95% CI: 1.06–1.85; Q4: OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.13–1.69), whereas sweetened coffee showed no significant association (p > 0.05). These findings suggest caffeine is a primary driver of the benefit, and adding sugar may attenuate it (Supplementary Table SIII).

Subgroup analyses (Table IV, Figure 4 based on significant interaction terms) defined “healthy intake habits” as morning consumption for ≤ 2 cups/day or all-day consumption for > 2 cups/day; other patterns were deemed “non-healthy”. Among adults aged 20–45 years, only healthy intake habits were significantly associated with higher eGDR (OR = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.10–1.50). In those aged 45–65 years, both healthy (OR = 1.48, 95% CI: 1.21–1.81) and non-healthy habits (OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.10–1.67) were beneficial, with a stronger effect for healthy habits. No significant association was observed in adults ≥ 65 years of age. Among women, both healthy (OR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.24–1.68) and non-healthy habits (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.13–1.60) were beneficial (stronger for healthy habits), while no association was observed in men. In non-hypertensive individuals, only healthy habits were beneficial (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.05–1.45). In hypertensive individuals, both habit types were beneficial: Healthy: OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.20–1.59; Non-healthy: OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.15–1.56), with a stronger effect for healthy habits. No significant association was observed in individuals with diabetes. The overall population association was consistent with the main findings.

Table IV

Effects of healthy drinking patterns on GDR levels

Discussion

Study findings

Building upon prior evidence, this study evaluated the impact of coffee intake timing and dose patterns on IR, using improvements in eGDR as the primary outcome. Our key finding is that coffee consumption, irrespective of morning or all-day patterns, was associated with improved IR. However, this benefit did not exhibit a linear dose-response relationship. Specifically, within the morning intake pattern, the association attenuated at higher consumption levels, while the all-day pattern demonstrated a progressively stronger association with increasing intake. Consequently, we propose an optimized chrono-nutritional approach: consuming lower amounts (≤ 2 cups/day) primarily in the morning and distributing higher amounts (> 2 cups/day) throughout the day may maximise IR improvement. Furthermore, the observed benefits appear primarily driven by caffeinated coffee and may be attenuated by added sugar, with stronger associations noted among women and individuals with hypertension.

Effects of different dose coffee intake patterns

The beneficial effects of coffee on metabolic health are well-documented. Landmark studies by the American Institute for Cancer Research [25, 26] and others have linked regular coffee consumption to reduced risks of dementia, cognitive decline, chronic liver disease, CVD, hypertension, Alzheimer’s disease, and certain cancers [27–32]. Given that IR serves as a fundamental pathophysiological link underlying these metabolic disorders, our findings, demonstrating coffee’s association with improved IR, provide a plausible mechanistic explanation for its broader health benefits. Importantly, an optimal intake window exists: moderate consumption (3–5 cups/day) is associated with the lowest CVD risk, while excessive intake shows no additional benefit and may pose health risks [33].

Caffeine, coffee’s primary psychoactive component, warrants careful consideration. Acute high-dose intake (> 400 mg/day) could induce adverse effects like tachycardia, nausea, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and polyuria [1]. Chronic excessive consumption is associated with decreased bone mineral density (increasing osteoporosis risk) [34], impaired glucose regulation, adverse pregnancy outcomes (elevated miscarriage risk) [35], and potential influences on tumourigenesis via metabolic pathways [36]. Our results align with this evidence, suggesting a plateau in IR benefit beyond moderate doses.

The impact of intake timing may relate to chrono-nutritional effects. Evidence indicates that meal timing influences long-term health outcomes, including CVD and all-cause mortality [37, 38]. Among individuals with T2DM, the classic manifestation of IR, coffee consumption from dawn to noon has been associated with increased mortality risk, whereas afternoon coffee/tea intake correlates with reduced all-cause mortality, CVD, and cardiac risk [39]. A prospective cohort study (n > 10,000) further demonstrated that pre-noon coffee consumption was associated with 16% lower all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.84, 95% CI: 0.76–0.93) and 44% reduced CVD mortality (HR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.48–0.65) versus non-consumers, benefits not observed with all-day consumption [13]. This temporal pattern may involve cortisol homeostasis: early-morning caffeine intake during peak cortisol secretion may exacerbate stress responses [40]. Integrating these findings with recent Korean data, we demonstrate that chrono-nutritional patterns significantly modulate IR sensitivity: lower intake (≤ 2 cups/day) maximises benefit when consumed before noon; higher intake (> 2 cups/day) requires distribution throughout the day. This framework confirms that strategically timed all-day consumption meaningfully impacts IR.

Our subgroup analysis specifically addressed the critical factor of added sweeteners, a subject of considerable scientific interest. Consistent with prior evidence, unsweetened coffee consumption is recommended over sweetened variants (mochas or macchiatos) [41]. Epidemiological data demonstrate that consuming > 2 cups/day of unsweetened coffee is associated with 5% reduced cancer risk (HR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.91–0.99) and 11% lower mortality risk (HR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.85–0.94). Conversely, > 2 cups/day of sugar-sweetened coffee correlates with 6% increased cancer risk (HR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.01–1.11) and 25% higher mortality risk (HR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.18–1.32). Notably, any sweetener addition (sugar or artificial) abolishes the protective effects and elevates risk [42]. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial further demonstrated that instant coffee supplementation did not significantly alter IR (ΔHOMA-IR: 4.0%; 95% CI: [–8.3, 18.0]; p = 0.53), showed no effect on fasting glucose (ΔFBG: 2.9%; 95% CI: [–0.4, 6.3]; p = 0.09), and failed to modulate IR biomarkers like adiponectin (Δ: 2.3%; 95% CI: [–1.4, 6.2]; p = 0.22) [43]. Nevertheless, coffee consumption demonstrated modest IR improvement across age, sex, and metabolic comorbidity subgroups when consumed without sweeteners.

However, the huge differences in coffee type, degree of roasting, and brewing patterns among people of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds could directly affect the final concentrations of caffeine and other bioactive substances. The effects observed in this study should be understood as “mixed effects” of multiple brewing modalities [44].

Mechanism of coffee improving IR

The beneficial effects of coffee on IR improvement are primarily mediated by its bioactive constituents, caffeine, cafestol, and chlorogenic acid, which exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Chlorogenic acid specifically enhances glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity through AMPK activation. Interestingly, caffeine demonstrates biphasic effects: acute intake transiently impairs insulin sensitivity, whereas chronic consumption confers improvements. Emerging evidence implicates gut microbiota modulation as a key mechanism [45]. Regular coffee consumers show increased abundance of butyrate-producing probiotics (Lactobacillus saccharolyticus and Lawsonibacter asaccharolyticus) that metabolise chlorogenic acid into active metabolites (quinic acid, caffeic acid). These compounds enhance insulin signalling, regulate microbiota via antioxidant-dependent pathways, and strengthen gut barrier function through butyrate production. Conversely, high sugar intake induces acute hyperglycaemia and oxidative stress, promotes IR via mTORC1 pathway inhibition, creates a tumour-permissive microenvironment through AMPK suppression, and causes gut dysbiosis and compromises immune defences.

Strengths and limitations

This study provides compelling evidence from nationally representative data confirming coffee’s association with IR improvement and introduces novel chrono-nutritional intake patterns. The rigorous analytical approach – incorporating multiple adjustment models, dose-response analyses, interaction testing, and subgroup stratification – enhances the validity of our conclusions regarding optimal coffee consumption timing. In addition, the association of timing of coffee intake with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality has been explored [18], but our study provides a mechanistic link by elucidating the effect on IR. We further emphasise that our analysis of dose-specific temporal patterns provides a deeper and more practical layer of insight for future research and public health guidance.

Several constraints warrant consideration:

Cross-sectional design – Precludes causal inference between coffee intake patterns and IR improvement.

Inconsistent evidence base – While coffee’s metabolic effects are established, consensus regarding IR-specific impacts remains elusive, particularly concerning temporal consumption patterns and coffee types.

Survival bias – Potential underrepresentation of severe metabolic comorbidities linked to advanced IR may limit generalisability compared to longitudinal cohorts.

Measurement limitations – Self-reported coffee consumption introduces possible recall bias and imprecision in timing documentation.

Clinical relevance gap – The exclusive focus on IR biomarkers rather than hard endpoints (diabetes incidence, cardiovascular outcomes) fails to answer whether the observed improvements translate to clinically meaningful benefits. lacking of quantitatively constant in the year and during life, as well as the age at which the coffee consumption starts in life. In addition, the metabolic equivalent criteria used to calculate physical activity are not uniform over the longitudinal years of data collection, so physical activity cannot be reported as in previous studies [46], and future studies should aim to use more uniform and refined physical activity assessment criteria to deeply investigate the potential effect modification or mediation of physical activity in the relationship between coffee intake and IR. These limitations highlight the need for prospective studies examining how chrono-nutritionally optimised coffee consumption affects progression to overt metabolic diseases.

In conclusions, our findings demonstrate that coffee consumption is associated with improved IR across both morning and all-day intake patterns. Notably, we identify an optimised chrono-nutritional strategy: Lower intake (≤ 2 cups/day) maximises benefit when consumed primarily before noon, while higher intake (> 2 cups/day) requires distribution throughout daytime hours. Caffeinated formulations without added sugar appear most effective. Coffee consumption habits in early life stages and their long-term health effects are important directions to focus on in future prospective cohort studies. Future research should elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying coffee’s IR modulation, validate these intake patterns in RCTs, assess longitudinal impacts on metabolic disease prevention, and develop integrated lifestyle interventions combining chrono-optimised coffee consumption with evidence-based nutritional and physical activity guidelines.