Introduction

Hearing loss is one of the most common sensory disorders [1]. The World Health Organization states that 360 million people worldwide have disabling hearing loss [2]. Hearing loss severely impairs the quality of life of patients, because of psychological alienation, social withdrawal, and increased depression and anxiety [3]. Hearing loss can be caused by multiple genetic and environmental factors [4]. Understanding the pathogenesis and deafness mechanisms underlying hearing loss is very critical to designing rational preventive strategies.

Hair cells of the inner ear cochlea are specialized sensory cells which convert vibratory stimuli into neural signals [5]. The loss of hair cells in the organ of the cochlea or Corti leads to a significant proportion of hearing impairment [6]. Moreover, hearing loss arises from various etiologies, such as over-stimulation of hair cells, ototoxic drugs, trauma to the head or gene mutations [7–9].

Noise-induced hearing loss is considered as a main cause of sensorineural hearing loss [10]. It has been reported that approximately 16% of hearing impairments are attributed to continuous exposure to loud noises [11]. Long-term exposure to noise levels beyond 80 decibels (dB) causes an increased risk of hearing loss [12]. With sufficient intensity and duration of noise, the hair cells may be severely disrupted [13].

Cisplatin is a widely used antineoplastic agent [14]. Ototoxicity is a major side effect of cisplatin, and often causes inner ear damage [15]. Hearing loss induced by cisplatin has been believed to occur in up to 80% of patients treated with cisplatin [16]. After injection, cisplatin accumulates in the inner ear fluids and then is taken up by the epithelial cells [15]. A previous study demonstrated that cisplatin leads to the death of hair cells [17].

In the present study, we investigated the effects of noise and cisplatin exposure on apoptosis and autophagy in the hair cells of the cochleae.

Material and methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Zhengzhou University. All mice were housed in a temperature controlled environment under specific pathogen-free conditions. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. All animal experimental procedures were approved according to the guidelines of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals by the National Institute of Health, China.

Noise and cisplatin mouse models of deafness

Mice (8–12 weeks, 22–30 g)) were divided into three groups: the control group (n = 10), the noise model group (n = 10) and the cisplatin model group (n = 10).

For noise exposure, mice were placed in a wire-mesh exposure cage with four shaped compartments and were able to move about within the compartment. The cage was placed in a MAC-1 sound-proof chamber designed by Industrial Acoustics (IAC, Bronx, NY) and the sound chamber was lined with sound-proofing acoustical foam to minimize reflections. Mice were exposed to white noise at 100 dB SPL (sound pressure level) with a central frequency (2–4 kHz) [18]. The noise exposure was sustained for 6 h/day for 3 consecutive days. For cisplatin treatment, mice were treated with furosemide (200 mg/kg, i.p.; 1 ml/day; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)) followed 1 h later by 1 mg/kg cisplatin (i.p.; Sigma) for 3 consecutive days.

Auditory brainstem response (ABR) measurements

Auditory function was examined using ABR as described previously [19]. In brief, mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (40 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Then, the mice were placed in a sound-isolated and electrically shielded booth (Acoustic Systems). Body temperature was maintained near 37°C with a heating pad. The ABR thresholds from both ears of the mice were detected using tone pips at 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 kHz. Thresholds were determined for each frequency by reducing the intensity in 10 dB increments. Thresholds were estimated between the lowest stimulus level where a response was observed and the highest level without a response. The data were recorded using Intelligent Hearing Systems (IHS; Miami, Florida).

TUNEL assay

Apoptotic hair cells were measured by TUNEL assay. Briefly, the animals were decapitated and the cochleae were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, followed by decalcification with 10% EDTA in PBS for 2 weeks, and then embedded in paraffin wax. The sections (5 μm) were incubated with an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche, Germany). Then, they were counterstained with DAPI (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, China) for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were observed under a confocal microscope (FV1200, Olympus, Tokyo; Japan).

Immunofluorescence

The cochlear sections (5 μm) were washed with PBS (0.1 M) 3 times, and then blocked with 10% goat serum for 30 min at room temperature. The tissue was incubated with primary antibodies against LC3-II (1 : 100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and myosin VI (1 : 400; Proteus Biosciences). After being washed with PBS for 3 times, the sections were incubated with Cy3- or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1 : 1000; Life Technologies) at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. DAPI (2 mg/ml; Beyotime) was used to stain the nuclei. Sections were visualized using a confocal microscope (FV1200, Olympus, Tokyo; Japan).

Western blot analysis

Whole cochlear protein was extracted as previously reported [20]. Protein concentrations were measured by a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Haimen, China). Proteins (30 μg) were separated by electrophoresis on 10–15% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad). After being blocked in TBST containing 5% milk for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against LC3 (1 : 500; Cell Signaling Technology), Beclin-1 (1 : 1000; Cell Signaling Technology), Bcl-2 (1 : 500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Bax (1 : 500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cleaved caspase-3 (1 : 500, Cell Signaling Technology), and GAPDH (1 : 1000; Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1 : 2000; Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. The bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Beyotime) and quantified with ImageJ software (v. 1.47t.; National Institutes of Health, USA). GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as means ± SD. GraphPad Prism v 6.0 (GraphPad Software Incorporated, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests were used for comparisons of data between groups. P < 0.05 was considered to be a statistically significant difference.

Results

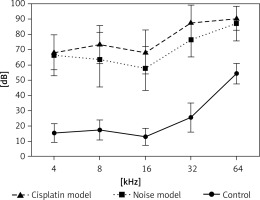

Hearing thresholds shift after noise and cisplatin exposure

Firstly, we examined noise- and cisplatin-induced hearing loss by ABR measurements. In Figure 1, the hearing thresholds of the mice were measured at various sound frequencies. The control mice showed normal ABR thresholds (10–50 dB SPL). However, the mice of the noise and cisplatin model showed deafness (70–90 dB SPL).

Noise exposures induce apoptosis and autophagy in the hair cells of the cochleae

To determine whether noise exposures induced apoptosis of the hair cells, we performed TUNEL staining to examine the cochleae from the mice. Few TUNEL-positive cells were detected in the control cochleae, while apoptosis was clearly seen in the cochleae from the noise model mice (Figure 2 A). Moreover, noise exposures significantly increased apoptotic markers, such as cleaved caspase-3 and Bax, but reduced the levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 (Figures 2 B, C).

Figure 2

Noise induces apoptosis and autophagy in the hair cells of the cochleae. A – Apoptotic cell death in the cochlea of mice. TUNEL staining was performed on the sections of the cochlea from control and noise model mice. B – Representative western blots of LC3, Beclin-1, Bax, Bcl-2, and cleaved caspase-3 protein expression in the whole cochlear extracts of mice. C – Quantification of the LC3-II, Beclin-1, Bax, Bcl-2, and cleaved caspase-3 proteins. D – Relative ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I. E – The cochlear sections were immunostained for myosin VI (green), LC3-II (red) and nuclei (blue)

*P < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared with the control group.

Next, to investigate the relationship between the noise exposures and autophagy, the autophagy biomarkers Beclin-1 and LC3 proteins (LC3-I and LC3-II) were assessed by western blot. LC3B-II and Beclin-1 proteins were strongly increased after noise exposure compared with the control group (Figures 2 B, C). Meanwhile, the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I was also increased significantly in the noise model group compared to the control group (Figure 2 D). Myosin VI is one of the hair cell-specific proteins [21]. There was a higher amount of LC3-II in the myosin VI hair cells after noise exposure than that in the control group (Figure 2 E).

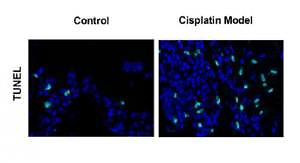

Cisplatin induces apoptosis and autophagy in the hair cells of the cochleae

Next, we extended our findings and determined the cell apoptosis after cisplatin damage. The number of TUNEL-positive cells was increased by cisplatin treatment compared with the control group (Figure 3 A). In addition, cleaved caspase-3 and Bax levels were considerably higher, while Bcl-2 level was significantly lower in the cochleae of mice treated with cisplatin (Figures 3 B, C).

Figure 3

Cisplatin induces apoptosis and autophagy in the hair cells of the cochleae. A – Apoptotic cell death in the cochlea of mice. TUNEL staining was performed on the sections of the cochlea from control and cisplatin model mice. B – Representative western blots of LC3, Beclin-1, Bax, Bcl-2, and cleaved caspase-3 protein expression in the whole cochlear extracts of mice. C – Quantification of the LC3-II, Beclin-1, Bax, Bcl-2, and cleaved caspase-3 proteins. D – Relative ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I. E – The cochlear sections were immunostained for myosin VI (green), LC3-II (red) and nuclei (blue)

*P < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 compared with the control group.

Finally, we analyzed the changes of autophagy factors in response to cisplatin. Higher protein levels of Beclin-1 and LC3-II were observed in the cisplatin model group than those in the control group (Figures 3 B, C). Also, the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I was substantially higher in the mice treated with cisplatin compared with the control group (Figure 3 D). Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining further confirmed that LC3-II levels were increased in the hair cells after cisplatin damage compared with the control group (Figure 3 E).

Discussion

Mouse models are often used for understanding the environmental and genetic factors to the development of hearing loss as well as the mechanisms underlying deafness [22]. Auditory brainstem response measurement is a common technique to test hearing abilities in a non-invasive way [23]. Hearing loss induced by noise exposure is thought to be on average greater than 40 dB in the lower frequencies and greater than 75 dB in the high frequencies [24]. In our study, we found that the control mice showed normal ABR thresholds (10–50 dB SPL). However, the mice of the noise and cisplatin model showed deafness (70–90 dB SPL). Therefore, the noise and cisplatin mice models for deafness were established successfully.

Recent findings have shown that the apoptotic program is an important contributing factor to hearing loss [25]. In cells, cisplatin induces replication-related DNA damage and thus apoptosis [26]. While cisplatin binding to DNA is the major cytotoxic mechanism in proliferating cells, ototoxicity appears to result from toxic levels of reactive oxygen species and protein dysregulation within various cellular compartments [27, 28]. Cisplatin has been shown to lead to apoptosis of cochlear cells in vitro and in vivo [29, 30]. Mukherjea et al. reported that increased TUNEL staining was observed in the cochleae from rats after cisplatin treatment for 3 days [31], which was in agreement with our study. The results were further strengthened by the observation of some biochemical apoptotic markers, such as caspase-3, Bcl-2 and Bax. Cisplatin significantly increased the active caspase-3 and Bax protein expression, but decreased Bcl-2 protein expression in the rat cochleae [32], which was in line with our study.

Noise exposure results in hair cell death primarily through apoptosis [33]. Several noise-induced events, including calcium influx, ATP depletion, and oxidative stress, play a role in exacerbating the pathological responses of sensory cells [34]. Moreover, noise exposure causes the activation of various biochemical pathways, including the JNK pathway [35], whose activation leads to apoptosis [36]. A previous study showed that the noise exposure triggered activation of caspase-3 in the hair cells of mice [37]. Our data showed more TUNEL-positive cells and increased cleaved caspase-3 and Bax protein expression, but decreased Bcl-2 protein expression, in noise-exposed cochleae. Therefore, exposure to noise and cisplatin promoted apoptosis of the hair cells in the cochleae.

Recently, several studies have shown that autophagy is related to auditory damage [38, 39]. During otic development, autophagy appears to be an active process in the avian inner ear [40]. Moreover, rapamycin, an inducer of autophagy, up-regulates the expression of LC3-II and Beclin-1 and reduces cisplatin-induced ototoxicity [41]. In contrast, treatment with 3-methyladenine, an autophagy inhibitor, inhibits LC3-II expression and augments temporary-to-permanent threshold shift [42]. Thus, hearing loss might be an autophagy-related disease. Our study reported that increased protein levels of Beclin-1 and LC3-II, and a higher ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I, were observed in the noise model and cisplatin model groups than those in the control group. Therefore, noise and cisplatin treatments elevated autophagy in the hair cells of cochleae. However, there was no further research about the signaling pathways activated in noise- or cisplatin-induced cochleae. Several pathways, such as ERK phosphorylation, are induced by mechanical damage and noise exposure [43]. Accordingly, blocking apoptotic signaling might diminish the extent of cochlear damage and hearing loss caused by noise or cisplatin [44].

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first publication demonstrating the effects of noise and cisplatin exposure on apoptosis and autophagy in the hair cells of the cochleae. Noise or cisplatin induces apoptosis and autophagy of the hair cells in the cochleae. This study provides new insights into the mechanisms of noise- or cisplatin-induced hearing loss.