Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a heterogeneous and etiologically complex syndrome [1]. Patients with HF often present with neuroendocrine and inflammatory activation, oxidative stress, ischemia, as well as congestion and hypoperfusion, which lead to multiorgan dysfunction [2, 3]. Despite major advances in diagnosis and therapy, HF is still associated with unacceptably high morbidity and mortality rates across the world, especially in the acute setting. While the gold standard biomarkers in management of HF are natriuretic peptides, several studies have shown the pathophysiological significance of numerous molecules involved in myocardial dysfunction, such as cancer antigen-125 (Ca-125), adrenomedullin (ADM), and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) [4].

In 1997, Japanese scientists identified the Klotho gene associated with aging phenotypes [5]. Since then, there has been interest in the Klotho gene and its correlation with lifespan and also with neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic conditions, cardiovascular damage, and heart dysfunction. The Klotho gene is expressed at particularly high levels in the kidney and brain and encodes the Klotho protein. Interestingly, this molecule was reported to have antitumor activity [6]. The main isotype of the Klotho protein is called α-Klotho. There are two forms of α-Klotho: a single-pass transmembrane glycoprotein, which works as a coreceptor for FGF-23, and secreted α-Klotho protein. The transmembrane type is cleaved by proteases and generates the so-called shed α-Klotho. Both secreted and shed forms belong to soluble α-Klotho proteins (sαKl) and are released into the blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid [7–9].

sαKl are pleiotropic proteins with endocrine, autocrine, and paracrine activation. In humans, the secreted form of sαKl predominates over the membrane form in serum [7]. However, in diseased heart cells, sαKl protein is upregulated and is derived from cleavage of the membrane form [8]. Several studies have documented that sαKl regulates mineral metabolism and inflammation and has antioxidative, antiapoptotic, and antifibrotic activity [10–13]. An experimental study in a rat model revealed increased compensative sαKl production during ischemia/reperfusion injury in cardiac cells as well as the release of sαKl protein into the extracellular space. Thus, sαKl can probably serve as a useful marker of cell injury [14].

It is known that oxidative stress activates matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) responsible for the degradation of contractile proteins in cardiomyocytes [15]. Additionally, the ARIC study indicated a link between increased plasma MMP levels and a higher risk of incident HF and arrhythmia [16]. By inhibiting MMPs, sα-Klotho can thus act as a cardioprotective agent [15]. It was also suggested that sαKl might be a novel predictor of response to treatment in the HF population [17]. Although a cross-sectional study showed that serum sαKl levels were negatively associated with chronic HF, little is known about the role of sαKl in patients with an acute episode of HF [18]. Considering its pleiotropic action, sαKl might prove to be a valuable biomarker in the setting of acute HF (AHF).

Thus, the aim of the current study was to assess the level and kinetics of serum sαKl during an episode of AHF and to establish the utility of sαKl in predicting long-term prognosis.

Material and methods

Study design

A total of 133 participants were enrolled in this study. The final sample included 112 consecutive patients admitted to the intensive cardiac care unit between June 2019 and January 2021. The follow-up lasted 3 years (Figure 1). All patients received guideline-guided therapy of AHF at the discretion of the attending cardiologist [1]. The inclusion criteria were age over 18 years and hospitalization for an episode of AHF diagnosed within 24 h of admission and requiring the use of at least one of the following: intravenous diuretics, catecholamines, or mechanical circulatory support. Patients with active malignancy, autoimmune disease, and psychiatric disorders were excluded.

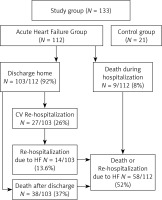

Figure 1

Flowchart of 3-year follow-up in the study group

AHF – acute heart failure, HF – heart failure, CV – cardiovascular.

The control group did not differ significantly from the study group in terms of age and sex. It included 21 individuals (mean [SD] age, 69 [17] years; 11 women and 10 men) without present or past acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafting, acute or chronic HF, acute kidney injury or chronic kidney disease. Median left ventricular ejection fraction was 65% (IQR: 60–65%). The blood samples were provided by the Biobank of Łukasiewicz Research Network – PORT Polish Centre for Technology Development.

The main clinical outcomes assessed in the study were 3-year all-cause mortality and rehospitalization due to HF.

Biochemical analysis

Blood samples (EDTA and clot samples) were collected during the first 24 h from admission to the hospital and then at discharge. Each EDTA sample was immediately centrifuged at 4000 RPM for 15 min to obtain plasma. The samples were then frozen at –80°C until analysis. Plasma sαKl levels were measured in duplicate, using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Human soluble α-Klotho ELISA, Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States). The serum levels of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) were measured quantitatively using an automated sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). For NT-proBNP, levels above 300 pg/ml were considered significantly elevated and for hs-cTnT, the level of 0.014 ng/ml was established as the upper limit of normal. Other biochemical parameters were obtained from the hospital laboratory and the Biobank database.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as either mean ± standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR), or count and percentages. The type of distribution was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences between groups were compared using the Student t-test for normally distributed variables and the Mann-Whitney U-test for non-normally distributed variables. The pairwise test was used to compare two parameters within a single group. The results were expressed graphically as box plots. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were conducted using the R software v. 4.2.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

General characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with AHF are presented in Table I. The group included 112 patients admitted to the intensive cardiac care with AHF.

Table I

Clinical characteristics of acute heart failure patient group

[i] BMI – body mass index, hs-CRP – high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, hs – cTNT – high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T, IVC – inferior vena cava, LVEDd – left ventricle end-diastolic dimension, LVEF – left ventricle ejection fraction, NT-pro BNP – N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide, TAPSE – tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, CRTD – cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator.

The mean (SD) age of patients was 65 (14.6) years; most patients were male. New-onset AHF was reported for 46% of the population. All patients suffered from multimorbidity and demonstrated significant HF with a median left ventricular ejection fraction of 30% (IQR: 20–38%). Nearly half of the population had a history of coronary artery disease. Patients in a critical condition were treated with catecholamines or using mechanical cardiac support.

Changes in biomarkers in the study group

In the whole study group, the median level of sαKl on admission was 670 pg/ml (IQR: 502–851 pg/ml). During hospitalization, sαKl levels decreased significantly to reach 542 pg/ml (IQR: 404–735 pg/ml) at discharge (p < 0.001). On admission, patients also presented with increased levels of NT-proBNP, hs-cTnT, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). Changes in the levels of these biomarkers are presented in Table I.

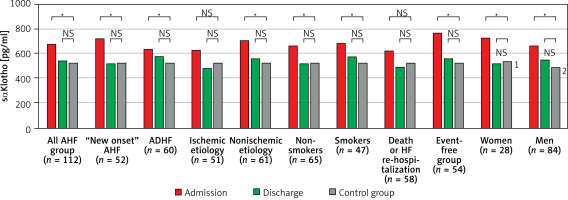

The levels of sαKl protein were similar between women and men on admission and at discharge (p = 0.39 and p = 0.89 respectively). In both sexes, a significant reduction in sαKl levels was noted between admission and discharge: from 724 pg/ml (IQR: 535–892 pg/ml) to 519 pg/ml (IQR: 453–640 pg/ml) in women (p = 0.002) and from 660 pg/ml (IQR: 501–836 pg/ml) to 550 pg/ml (IQR: 400–836 pg/ml) in men (p < 0.001). On admission, serum sαKl levels in women and men were significantly higher in the study group vs. the control group (p = 0.049 and p = 0.03 respectively); Figure 2.

Figure 2

Comparison of sαKlotho concentration in serum by subgroups with control group at admission and discharge

ADHF – acute decompensated heart failure, AHF – acute heart failure, HF – heart failure, sαKlotho – soluble α Klotho; NS – not significant; *p < 0.05. Control group (n = 21). The median level of saK1 522 pg ml (IQR: 408–624 pg ml). (1) Control group for women (n = 11). The median level of sαK1540 pg/ml (IQR: 428–636 pg/ml). (2) Control group for men (n = 10). The median level of sαK1493 pg/ml (IQR: 379–550 pg/ml).

In patients with the new-onset AHF, as well as with acute decompensated HF, serum sαKl levels on admission were significantly higher than at discharge, 713 pg/ml (IQR: 525–886 pg/ml) vs. 517 pg/ml (IQR: 403–667 pg/ml), p < 0.001 and 634 pg/ml (IQR: 502–836 pg/ml) vs. 573 pg/ml (IQR: 406–784 pg/ml), p = 0.002. Of note, sαKl values on admission and discharge in both groups did not differ considerably (p = 0.45 and p = 0.31 respectively). There were significant differences in sαKl levels at admission in both groups compared with the control group (p = 0.006 and p = 0.02 respectively); Figure 2.

In patients with AHF of ischemic etiology, sαKl levels decreased significantly between admission and discharge, 614 pg/ml (IQR: 461–810 pg/ml) vs. 484 pg/ml (IQR: 391–725 pg/ml), p < 0.001. Similarly, in the nonischemic subgroup, there was a significant reduction in sαKl levels between admission and discharge, 711 pg/ml (IQR: 556–895 pg/ml) vs. 552 pg/ml (IQR: 437–736 pg/ml), p < 0.001. A comparison of admission and discharge sαKl levels between ischemic and nonischemic etiology revealed that there were no differences (p = 0.07 and p = 0.26, respectively). In the nonischemic group, on admission, we observed significantly increased sαKl levels as compared with the control group (p = 0.001); Figure 2.

In the study group, 39% were smokers. sαKlotho values in the groups of smokers and non-smokers did not differ on admission and at discharge (p = 0.64 and p = 0.49, respectively). In both groups, sαKlotho values dropped markedly between admission and hospital discharge: from 677 pg/ml (IQR: 475–892 pg/ml) to 573 pg/ml (IQR: 402–831 pg/ml), p = 0.007, in the smoker group and from 664 pg/ml (IQR: 525–837 pg/ml) to 515 pg/ml (IQR: 410–711pg/ml), p < 0.001, in non-smokers. In both groups, significantly higher sαKlotho values were observed on admission compared to the control group (p = 0.049 and p = 0.003, respectively); Figure 2.

Associations between sαKl levels and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with AHF

Nine (8%) patients died during hospitalization, and 103 (92%) patients were discharged from the hospital. During the 3-year follow-up, 27 of the 103 (26%) patients were hospitalized due to cardiovascular events, including 14 rehospitalizations (13.6%) due to HF. Death was reported for 38 (37%) patients. Thus, the combined endpoint – all-cause mortality or rehospitalizations due to HF – was reached in 58 (52%) patients. The patient flowchart is presented in Figure 1.

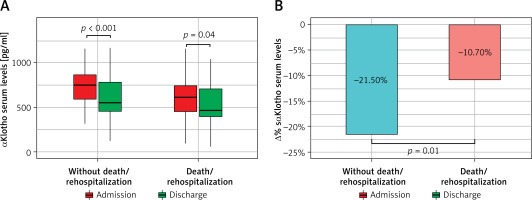

Patients who developed the combined endpoint during follow-up were older, more often had acute decompensated HF phenotype, HF of ischemic etiology, chronic kidney disease and diabetes. They also had higher concentrations of hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP; Table II. In this subgroup, sαKl levels decreased significantly from admission to discharge, 614 pg/ml (IQR: 459–746 pg/ml) vs. 490 pg/ml (IQR: 391–719 pg/ml), p = 0.04; Figure 3 A.

Table II

Selected parameters of AHF patients, stratified according to 3-year all-cause mortality or heart failure rehospitalization

[i] ACEi – angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ALT – alanine transaminase, AST – aspartate transaminase, ARB – angiotensin receptor blocker, CKD – chronic kidney disease, eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate, hs-CRP – high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, hs-cTNT – high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T, MRA – mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, NT-pro BNP – N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide, SGLT2i – sodium glucose Co-transporter-2 inhibitor.

Figure 3

Changes of sαKlotho values during hospitalization in subgroups stratified by clinical course during 3-year follow-up. A – Absolute values (median and interquartile range). B – Relative change (%)

The subgroup that was free from cardiovascular events during follow-up showed significantly higher sαKl levels on admission as compared with the group with adverse outcomes (p = 0.003), Table II, as well as with the control group (p < 0.001), Figure 2. Additionally, these patients showed a strong reduction in sαKl levels during hospitalization, 765 pg/ml (IQR: 594–880 pg/ml) vs. 553 pg/ml (IQR: 453–784 pg/ml), p < 0.001, Figure 3 A. Both groups differed significantly in percentage sαKl reduction between admission and discharge (p = 0.01); Figure 3 B.

sαKl in the control group

In healthy individuals, serum sαKl levels decrease physiologically because of the aging process [19]. The median level of sαKl protein in the control group was 522 pg/ml (IQR: 408–624 pg/ml).

Correlations between sαKl levels and other biomarkers

On admission, sα-Kl levels showed a weak negative correlation with the levels of NT-pro BNP (r = –0.21, p = 0.03) and hs-CRP (r = –0.26, p = 0.006). No significant correlation with hs-cTnT was found (r = –0.14, p = 0.13). At discharge, sαKl showed a weak negative correlation with NT-pro BNP and hs-CRP (r = –0.33, p = 0.002 and r = –0.32, p = 0.002, respectively).

Discussion

Our study showed that in critical conditions such as AHF, sαKl levels increase irrespective of sex, HF etiology, or HF phenotype. Serum levels of sαKl protein are dynamic and decrease during optimal treatment of AHF. Moreover, the study showed a negative association between sαKl levels and 3-year risk of all-cause mortality or HF rehospitalization.

sαKl is a protein with anti-inflammatory action, reducing oxidative stress and fibrosis caused by the activity of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [7, 9, 19]. Experimental data from a mouse model suggested cardioprotection with antifibrotic and antihypertrophic action [20]. It is known that sαKl levels decrease with age; therefore, the serum biomarker concentration may indicate the biological age. Various studies, however, have reported different reference ranges for the sαKl protein [21, 22]. Obesity, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes, which are potential risk factors for cardiovascular disease, are associated with low serum sαKl levels [23, 24]. A meta-analysis of American populations suggested that low sαKl levels are associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality [25]. The above evidence indicates that sαKl plays a protective role in the body. Recent studies investigated changes in the levels of circulating sαKl, its reference ranges in acute cardiac conditions, and the use of sαKl as a biomarker of myocardial injury [15] and response to psychological stress [26]. Numerous data indicate that sαKl may improve the function of aging cells [27].

In our study, we assessed changes in sαKl in patients with AHF. In line with the study by Taneike et al. [17], we noted significantly elevated sαKl levels compared with the control group. The levels of sαKl were assessed in subgroups according to sex as well as the phenotype, smoking habits and etiology of AHF. On admission, we noted considerably elevated sαKl levels in patients with new-onset HF and nonischemic etiology, as compared with the control group. In these patients, treatment resulted in a significant reduction in sαKl levels between admission and discharge. These findings are not surprising and confirm worse survival in patients with ischemic etiology of HF [28] and poor prognosis in those with acute decompensated HF linked to multiorgan damage [29, 30].

Sex, a non-modifiable risk factor, was also of our interest. Espuch-Oliver et al. investigated 345 healthy Andalusian volunteers and observed a negative association between sαKl levels and age, while there was no relationship with sex [21]. In an analysis of 19 patients (9 women) hospitalized for AHF, Taneike et al. found that sαKl levels were higher in men [17]. In our study, women constituted 25% of the whole population. Unlike Taneike et al., we did not observe significant differences in sαKl levels between women and men. On admission, both women and men with AHF had significantly higher sαKl levels than controls. This discrepancy might be due to different geographical regions, living conditions, and race [31].

It is known that smoking is related to premature aging, causes systemic inflammation, and leads to various disorders such as cardiovascular disease. However, the relationship between Klotho and smoking not entirely clear. Nakanishi et al. reported that smoking and psychological stress increase the level of sαKlotho in healthy individuals, suggesting compensation for harmful effects of smoking [32]. Onmaz et al. found significantly decreased sαKlotho levels in smokers compared to non-smokers [33]. In our study, smokers and non-smokers had significantly elevated sαKlotho values on admission compared to the control group. The two groups did not differ on admission and at discharge (p = 0.64 and p = 0.49, respectively). This finding may mean that smoking in our population of AHF patients was not important in sαKl dynamics.

Risk stratification in AHF is a major goal and crucial for better identification of high-risk patients, who need close, much more intensive in-hospital treatment and monitoring after discharge. On the other hand, low-risk patients may be discharged from hospital early and monitored in ambulatory care. It seems that sαKl could be a useful tool in risk assessment.

Our short, preliminary 12-month follow-up showed a small decrease in sαKlotho levels among patients with death or HF rehospitalization; Supplementary Figure S1.

Prolonged 3-year observation revealed that patients free from cardiovascular events had significantly higher sαKl levels on admission than the control group. Moreover, we noted a major reduction in sαKl levels between admission and discharge in both groups; Figure 3 A.

Patients who met the composite endpoint (death or HF rehospitalization) during the 3-year follow-up demonstrated significantly lower sαKl levels on admission compared to patients free from cardiovascular events. There were also significant changes in the levels of the biomarker during hospitalization (Figure 3 A); however, this group was characterized by a 2-fold lower reduction of sαKlotho values between admission and discharge compared to patients free from cardiovascular events; Figure 3 B. Interestingly, at discharge, sαKl levels were lower than in the control group; Figure 2. Our findings suggest that sαKl probably has cardioprotective effects, and its production in AHF constitutes a compensatory reaction to oxidative stress and the inflammatory response. Higher sαKl levels on admission were associated with a lower risk of death or rehospitalization due to HF during short 12-month and prolonged 3-year follow-up. A weak reduction in sαKl levels between admission and discharge may serve as an indicator for a poor prognosis. It seems likely that supplementation with sαKl in these patients will improve their prognosis. Data from studies on an animal model strongly suggest that replenishment of sαKl protects against fibrosis in renal and cardiac diseases. sαKl was also found to be a tumor growth inhibitor and potential therapeutic agent to promote the healing of aged injured skeletal muscles [6, 27]. The therapeutic potential of sαKlotho is a robust area of study for the development of sαKL-based pharmaceuticals. Recent publications report that small sαKl boosting molecules and gene therapy are intensively pursued by industry [6]. Findings from our study are in line with previous data [17] that confirmed the usefulness of sαKl in AHF, both as a biomarker and promising cardioprotective agent. Taking into account current knowledge [34], this novel, valuable molecule has potential for extensive use, especially in screening health services and preventive medicine. The widespread use of sαKl, as a biomarker in the early diagnosis and management of age-related diseases, may help select high-risk patients and facilitate therapeutic decision-making. Notably, early diagnosis may be cost-effective, for example in heart failure. Given the therapeutic potential of sαKl, it may influence the management of many conditions and disorders. We believe that ongoing research and clinical efforts are bringing us closer to application of this assay in everyday clinical practice.

First, this study had a limited number of enrolled patients. Thus, our findings should be confirmed in a survey with a larger sample size. Second, although we conducted therapy in accordance with the latest guidelines for HF, our study did not include a specific therapy protocol. Many non-cardiovascular medications and nutraceuticals could affect the serum sαKl levels. It would be useful to perform an analysis of several medications affecting the sαKl level.

In conclusion, our study showed that the sαKl level is upregulated during an acute episode of HF. Thus, it may be a useful biomarker for diagnosis and treatment. Poor kinetics in sαKl levels during treatment indicate patients with bad prognosis in the long-term observation. Subjects with higher sαKl levels at admission tended to present better outcomes, suggesting a promising cardioprotective role of this biomarker in AHF.