Introduction

Acute coronary syndromes (ACS) encompass a spectrum of conditions such as acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and unstable angina (UA) [1]. The ACS pathophysiology is highly complex and involves bone marrow activation and inflammation [2].

After AMI, human bone marrow increases activity and releases hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) into the circulation [3, 4]. Stimulated by hematopoietic growth factors, these progenitor cells can migrate to the spleen, where they multiply. The proinflammatory monocytes then leave the spleen and enter atherosclerotic plaques. Once there, they promote inflammation, making the plaques more likely to cause thrombosis, and consequently, AMI [5]. These monocytes also accumulate in injured tissues and participate in wound healing [6].

Recent research has revealed the inflammatory signaling networks that connect the brain, autonomic nervous system, bone marrow, and spleen to atherosclerotic plaques and infarcted myocardium. According to Libby et al., these new findings expand the traditional concept of the “cardiovascular continuum” beyond the heart and blood vessels by including the nervous system, spleen, and bone marrow in its spectrum [7].

It is known that cardiovascular diseases (CVD) cause endothelial dysfunction, leakage, vascular fibrosis, and angiogenesis in the bone marrow’s vascular niche, leading to increased hematopoiesis and the production of inflammatory leukocytes [8]. Patients with ACS who exhibit elevated levels of baseline inflammatory markers are at increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, particularly cardiovascular death.

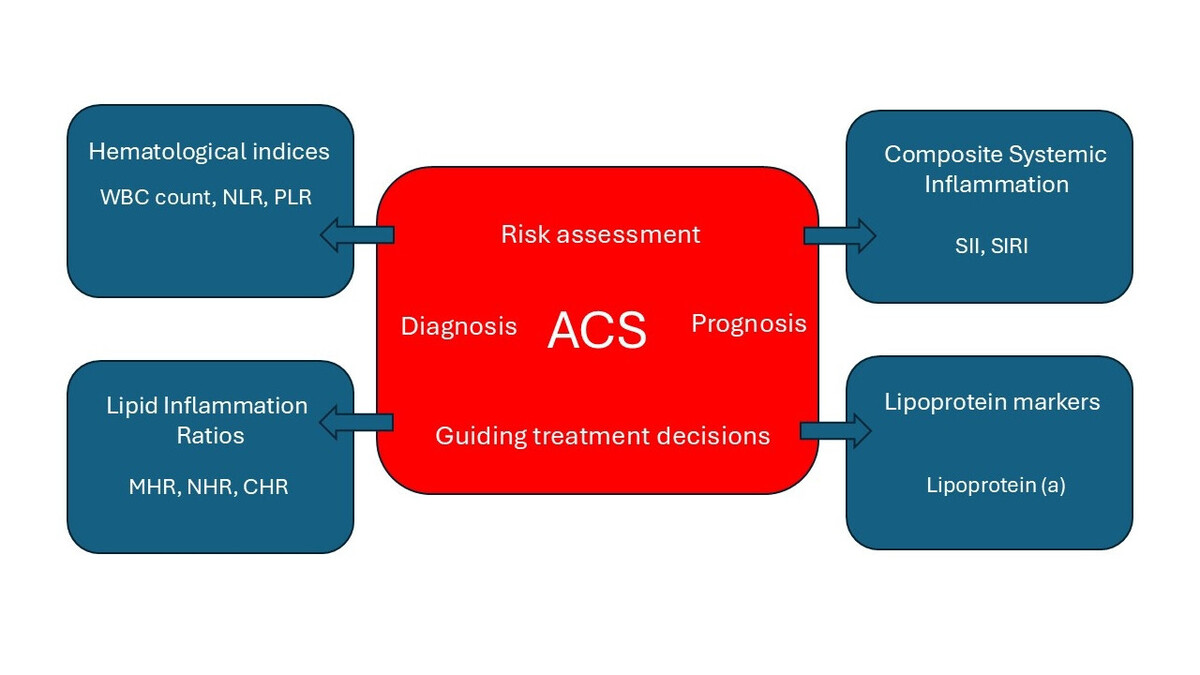

Hematological indices are simple, inexpensive and easily available biomarkers derived from the complete blood count [2]. Inflammatory and lipid biomarkers can further improve the selection of patients with ACS who would most likely benefit from anti-inflammatory therapy [9]. In this update review, we focus on data published since our previous review in 2017 [2]. Figure 1 illustrates the major categories of these biomarkers and their clinical role in the context of ACS.

Figure 1

Summary of biomarker categories and their clinical utility in the context of ACS

ACS – acute coronary syndrome, WBC – white blood cell count, NLR – neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR – platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, MHR – monocyte-to-HDL ratio, NHR – neutrophil to HDL-C ratio, CHR – high-sensitivity CRP to HDL-C ratio, SII – systemic immune-inflammation index, SIRI – systemic inflammation response index.

White blood cell count (WBC)

Leukocytes play a major role in the pathophysiology of ACS. The recognition of leukocytosis as a response to MI dates back several decades. They coordinate the mechanisms of innate immunity [10]. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes can promote endothelial damage during superficial erosion [11]. In a large prospectively followed cohort of patients at a high risk of incident coronary events, the WBC count was identified as an independent predictor of death/MI [12]. In the multicenter, prospective, observational PARIS study (Patterns of Non-Adherence to Anti-Platelet Regimens in Stented Patients Registry), increased WBC was an independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), which was linked to cardiac death, stent thrombosis, spontaneous myocardial infarction (MI), or target lesion revascularization at a 24-month follow-up after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [13].

Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR)

Neutrophils have demonstrated important functions during cardiovascular inflammation and repair. Neutrophils can participate in superficial plaque erosion or fibrous cap rupture [11]. These cells accelerate all stages of atherosclerosis by fostering monocyte recruitment and macrophage activation [14]. Neutrophil secretory products not only attract but also activate macrophages. Activated neutrophils release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) composed of chromatin via NETosis, a cell-death program different from apoptosis or necrosis [15]. Mangold et al. detected NETs throughout coronary thrombi, serving as a primary scaffold for platelets, erythrocytes, and fibrin [16].

Following ischemic injury, there is an initial scarcity of lymphocytes within the infarct, which prompts their rapid proliferation within the adjacent draining lymph nodes [17]. The absolute lymphocyte count is negatively associated with CV events [17].

Among the leukocyte subtypes studied there, the neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, and NLR were significant independent predictors of death or MI. However, the markers mentioned along with NLR appeared to have a greater predictive value [12].

NLR is an easily obtained inflammatory biomarker whose effectiveness as a predictor of cardiovascular risk in primary and secondary prevention scenarios has been supported by academic research [18]. It is still unknown whether NLR (independent of hsCRP) is linked to atherosclerotic events. Moreover, while the independent prognostic significance of NLR has been established across various diseases, determining its precise normal cut-off value remains a subject of ongoing debate [19].

In all five contemporary randomized trials (JUPITER, CANTOS, SPIRE-1, SPIRE-2, and CIRT), NLR consistently predicted future cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality [18]. The advantage of the NLR index is that it remains constant during subsequent measurements, increasing its potential as a useful biomarker in clinical practice.

The data on drug response to canakinumab – an interleukin-1β inhibitor – suggest the potential for use of NLR to monitor the effectiveness of emerging anti-inflammatory strategies for atherothrombosis [18].

In a meta-analysis of 90 studies based on the data of 45,990 participants, Pruc et al. found that NLR was associated with mortality in ACS, with the survivors having lower results (3.67 ±2.72 vs. 5.56 ±3.93) [20]. The subanalysis showed that NLR differed in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) among the survivors (4.28 ±3.24 vs. 6.79 ±3.98). Among the ACS patients with MACE versus those without MACE, NLR was 6.29 ±4.89 vs 3.82 ±4.12 [20].

Another meta-analysis indicated that the pretreatment NLR value of 5.0 might be a cut-off value for ACS risk [21]. The combination of D-dimer and NLR was associated with long-term MACE in ACS patients who underwent PCI [22]. Interestingly, in a Korean nationwide prospective cohort, the combination of NLR and anemia on admission was strongly associated with all-cause mortality after STEMI [23].

Increased NLR was independently associated with the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS) patients treated with PCI [24]. In another study, elevated NLR, but not platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), was an independent predictor of CIN among patients with AMI [25]. However, higher NLR and PLR in post-AMI patients were independent predictors of left ventricular thrombosis resolution failure only among patients who did not undergo PCI [26].

Patients with ACS who underwent PCI despite receiving aspirin (ASA) and ticagrelor as dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) turned out to have a notably elevated inadequate platelet inhibition when NLR exhibited higher values [27]. Long-term mortality and the likelihood of experiencing recurrent major ischemic events were also found to be correlated with NLR.

Platelet to lymphocyte ratio

PLR has been linked to heightened inflammatory activity and a significant pro-thrombotic state. Higher PLR was an independent risk factor for the development of CIN in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI [28]. Oylumlu et al. found that a high PLR level was an independent predictor of long-term poor prognosis in ACS patients [29]. A meta-analysis revealed that PLR is a promising biomarker in predicting both in-hospital and long-term poor prognosis in ACS patients [30]. A meta-analysis including 11 cohort studies and a total of 12,619 patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) demonstrated that elevated preprocedural PLR was independently associated with a significantly increased risk of in-hospital MACE, cardiac mortality, all-cause mortality, and the no-reflow phenomenon. Furthermore, elevated PLR was a significant predictor of MACE and all-cause mortality during long-term follow-up periods extending up to 82 months after discharge [31].

Neutrophil to HDL-C ratio (NHR)

NHR is a novel marker that reflects inflammation and lipid metabolic disorders. Kou et al. found that NHR was associated with coronary artery stenosis and served as an independent predictor of coronary artery disease (CAD) [32].

Ren et al. reported that NHR was higher in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 (T2DM) combined with ACS than in T2DM patients without ACS [33]. The same study also showed that the diagnostic power of NHR was stronger in ACS patients with elevated ST-segment (STE-ACS) than in NSTE-ACS patients (p < 0.001) [33].

Huang et al. suggested that NHR may have predictive value for prognosis in long-term mortality and recurrent MI in older patients with AMI [34]. In the study by Chen et al., NHR was independently associated with increased incidence of in-hospital MACE in STEMI patients treated with PCI [35]. NHR outperformed other hematological and lipid indices, including monocyte to HDL-C ratio (MHR) and LDL-C/HDL-C, in predicting the prognosis for patients with AMI [35].

hsCRP to HDL-C ratio (CHR)

The use of inflammatory markers in combination with lipid markers may improve the prediction of cardiovascular events to a greater extent than either marker alone.

According to Gao et al., high CHR is a significant risk factor for CVD, stroke, and heart problems [36]. The study by Luo et al. showed that CHR was an independent predictor of severe CAD, with better diagnostic performance than NLR [37].

In the study by Tang et al., HDL levels did not accurately reflect HDL’s functional status in patients with CAD. CAD patients with higher hsCRP levels had larger HDL particles (HDL1) and fewer small HDL particles (HDL4) [38]. In another prospective cohort study involving 3,260 patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), elevated CHR was independent risk factor for long-term all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, and MACE [39].

These studies underscore the significance of the CHR as a composite marker reflecting the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic factors in cardiovascular health. An elevated CHR is associated with increased risk and severity of ACS and related adverse outcomes.

Monocyte to HDL-C ratio

MHR was an independent predictor of CAD severity and future cardiovascular events in patients with ACS [40].

A high value of MHR among the STEMI patients who underwent primary PCI was associated with higher in-hospital mortality and MACE [41]. The study by Guo et al. demonstrated that HDL-C-related inflammatory indices (monocyte-to-HDL-C ratio, neutrophil-to-HDL-C ratio and lymphocyte-to-HDL-C ratio) independently predicted repeated revascularization after coronary drug-eluting stenting. MHR exhibited a dose-response relationship and showed a linear correlation with the incidence of repeat revascularization [42]. The meta-analysis incorporated eight studies including a total of 6,480 patients diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) [43]. The results indicated that an elevated MHR was significantly associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (risk ratio [RR]: 1.65) and all-cause mortality (RR = 2.61). Importantly, the prognostic significance of MHR was consistent across both short-term (in-hospital) and long-term (beyond 6 months) follow-up periods [43].

Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI)

Two innovative inflammatory markers have recently been introduced into clinical practice: the SII and the SIRI. These markers are composed of platelet counts and three subtypes of leukocytes. The SIRI measures inflammation by combining the absolute counts of three types of inflammatory cells: neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes [44]. SII is defined as platelet count × neutrophil count)/lymphocyte count [44]. They may be associated with the risk of overall stroke and all-cause mortality [44]. SIRI, but not SII, has been positively associated with MI incidence [44]. This association was significant only in individuals under the age of 60. It was found that both SII and SIRI exert effects that are independent of C-reactive protein (CRP) levels [44].

Among the five lymphocyte-based inflammatory indices including PLR, NLR, and monocyte-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), SII and SIRI were significantly and independently associated with MACE in ACS patients who underwent PCI [45]. In another study, SIRI was a strong and independent risk factor for MACE in patients with ACS undergoing PCI [46].

SII and SIRI were higher among patients diagnosed with STEMI, NSTEMI and UA compared to those with stable CAD. The highest SIRI values were observed in three-vessel CAD [47]. Fan et al. found that a higher SII and derived NLR (dNLR) were independently associated with a higher risk of developing all-cause mortality and rehospitalization for severe heart failure in patients with ACS undergoing PCI [48].

Lipoprotein(a)

Lp(a) is a lipoprotein composed of a low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-like particle and a specific apolipoprotein(a). It is mostly genetically determined (70–90%). Lp(a) can be used as a marker for residual cardiovascular risk in patients with ACS. Epidemiologic and genetic studies support a causal association between Lp(a) concentration and cardiovascular outcomes [49]. Lp(a) has pro-inflammatory and pro-atherosclerotic properties, which may partly relate to the oxidized phospholipids carried by Lp(a). The widely used cardiovascular risk assessment tools for primary prevention do not incorporate Lp(a) levels. However, in the context of primary prevention, high levels of Lp(a) are associated with various atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease outcomes, aortic valve stenosis, and both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [50–53]. Elevated levels of Lp(a) are recognized as an independent risk factor for ACS, with particular clinical relevance in individuals who present with normal lipid profiles or experience premature and recurrent cardiovascular events despite receiving optimal medical therapy. Moreover, Lp(a) was independently associated with ACS in younger individuals (< 45 years), and high Lp(a) levels increased by approximately threefold the risk for ACS [54]. Measurement of Lp(a) during the acute phase of ACS is not recommended, as circulating levels are frequently elevated due to the acute-phase response [53]. However, assessment of Lp(a) at the time of hospital discharge or during early follow-up is of significant clinical importance. Such evaluation may provide prognostic insight and support risk stratification efforts aimed at preventing recurrent cardiovascular events [54]. In 2021, for the first time, the Polish guidelines issued by six scientific societies on managing lipid disorders incorporated an elevated Lp(a) concentration of over 50 mg/dl (125 nmol/l) as an additional criterion for identifying extremely high cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes following ACS [55]. Polish guidelines recommend Lp(a) measurement in all patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) [49]. Emerging therapies specifically targeting Lp(a), notably antisense oligonucleotides such as pelacarsen and small interfering RNA (siRNA) agents including olpasiran and lepodisiran, represent a significant advancement in the therapeutic landscape for managing cardiovascular risk in individuals with elevated Lp(a) concentrations [56].

Future perspectives

Artificial intelligence (AI)

Artificial intelligence (AI) is an essential element of clinical decision-aid systems.

In the study by Yilmaz et al., a thorough data analysis was conducted, employing the Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) model along with explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) to explore the potential hematological predictors of AMI [56]. The model which included the 10 most important hematological parameters achieved 83% and 74% accuracy for predicting AMI and distinguishing subgroups of AMI (STEMI and NSTEMI), respectively. The analysis of the AMI output revealed that the features of neutrophils, WBC, platelet distribution width (PDW), and basophils are of utmost significance in diagnosing AMI patients [57].

Another study tried to develop risk models based on widely available, simple hematologic predictors which included hematocrit, hemoglobin concentration, mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean platelet volume (MPV), platelet count (PLT), red blood cell count (RBC), and red cell volume distribution width (RDW) [58]. The above hematologic indices had predictive value for cardiovascular outcomes above and beyond traditional risk factors.

According to Truslow et al., hematology-based models modestly predict incidents of ACSs beyond what was possible using only age and prior diagnoses [58]. It was suggested that a strategy combining age and hematologic indices may be more accurate in predicting incident ACS [58].

Genetics

A Mendelian randomization study using data from the UK Biobank and the Japan Biobank revealed that the RBC count, hemoglobin levels, hematocrit, and uric acid levels independently influence the CAD risk, independently of traditional cardiometabolic factors [59]. It was proposed that targeting the physiology of red blood cells and managing uric acid levels could serve as potential interventions for preventing CAD [59].

MPV is the primary measure of platelet size and is strongly associated with platelet reactivity. There are conflicting results concerning the relationship between MPV and ACS. Some studies have demonstrated a significant association between MPV and AMI, whereas most studies have not found such a relationship [60, 61]. The research by Kunicki et al. revealed that MPV was the most significant factor influencing the variation in levels of platelet integrin αIIbβ3 (a receptor for fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor), both in healthy individuals and patients with ACS [62]. Due to the increased activity of larger platelets, MPV serves as a reliable indicator of risk for adverse outcomes in ACS [62].

Discussion

The pathophysiology of inflammation and atherosclerosis is highly complex. Bone marrow activation and inflammation, whether chronic or acute, might be an undermined risk factor. Many patients with AMI do not have elevated LDL-C levels but do show signs of increased inflammation. According to Ridker, patients who have experienced AMI are more likely to have residual inflammation rather than elevated LDL-C levels [63]. The CANTOS study provided evidence supporting this hypothesis. Inhibiting the progression of inflammation led to a significantly lower rate of recurrent cardiovascular events independent of lipid-level reduction [64]. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) should be considered a substrate for the lipid core. The danger associated with this fraction lies in its susceptibility to oxidation (only when modified in this way does the particle have a causal relationship with atherosclerotic plaque formation). The susceptibility of LDL to oxidation is directly linked to an increased redox potential, which may result from heightened inflammatory states. In light of this paradigm, anti-atherosclerotic treatment should focus on reducing inflammation and the concentration of substrates involved in plaque formation.

The increased movement of leukocytes to the plaque after AMI relies on the movement of progenitor cells from bone marrow. This process precedes extramedullary hematopoiesis and contributes to the continuous build-up of leukocytes within the atherosclerotic lesion [5].

Hematological indices were selected because numerous factors contributing to chronic diseases such as CVD are systemic and may manifest across various tissue types [58]. Furthermore, hematological indices may be used to create AI-based cardiovascular risk models from the clinical electronic health record data [58]. The findings from these studies can pave the way for more targeted anti-inflammatory therapies and guide future drug development strategies [18].

Most recent studies also show direct head-to-head comparisons of hematological indices (RDW, MPV, NLR, PLR, MHR) for predicting the mortality risk in ACS patients [65, 66]. According to Sigirici, NLR had the largest area in the receiver operating characteristic curve. NLR can be used to predict in-hospital mortality in STEMI patients [64]. By contrast, RDW and the MHR are superior hematological indices for forecasting long-term mortality after STEMI compared to other common biomarkers [65]. Interestingly, in another study, Li et al. found that the novel parameters SII and SIRI are more comprehensive than PLR, NLR, and MLR, since they combine three types of inflammatory cells [66]. SIRI was considered more successful in predicting MACE than PLR, NLR, MLR, and SII [66].

Limitations

Given that NLR is derived from the ratio of two absolute cell counts, any physiological condition that selectively impacts neutrophils or lymphocytes will inevitably affect NLR. These conditions comprise acute hematological malignancies, inflammation, immune deficiencies, and the use of immunomodulatory medications [18]. For example, lipid-lowering therapies had no significant effect on NLR, while methotrexate increased it, and canakinumab reduced it [18]. NLR may also increase in response to physiological stress, given that glucocorticoids induce relative neutrophilia and lymphopenia. There are insufficient data available to determine whether elevated NLR plays a role in atherosclerotic events.

Studies concerning hematological indices often have a retrospective design, which may undermine the conclusions. Most researchers chose to measure the parameters only at admission, rather than taking multiple repeated measurements. Another limitation is that some research was carried out in a single center and the study population size was small, so multicenter and large-scale studies are needed to verify these conclusions.

Conclusions

The prognostic significance of inflammatory markers in cardiovascular diseases has gained particular prominence following the publication of the CANTOS study, which clinically validated Ridker’s hypothesis regarding the inflammatory etiology of atherosclerosis [64]. This study has also expanded the former understanding of cardiovascular risk based solely on assessing concentrations of substrates involved in development of atherosclerotic plaque.

There is a great demand for an easily available, noninvasive hematological marker for prognosis in ACS patients. Such a marker would help identify high-risk cardiovascular patients for secondary prevention and allow individual therapy adjustments. Numerous studies have highlighted the importance of hematological indices in determining the prognosis of ACS, as demonstrated earlier. Recent advancements in AI will enable the development of models that aid the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients with ACS. By examining easily available hematological indices, healthcare providers will be better equipped to make well-informed decisions and deliver improved care to a diverse patient population. A summary of their benefits, limitations, and research gaps is presented in Table I.

Table I

Summary of biomarker categories in ACS: benefits, limitations, and future perspectives

[i] CBC – complete blood count, ACS – acute coronary syndrome, WBC – white blood cell count, NLR – neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, PLR – platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, MHR – monocyte-to-HDL ratio, NHR – neutrophil to HDL-C ratio, CHR – high-sensitivity CRP to HDL-C ratio, SII – systemic immune-inflammation index, SIRI – systemic inflammation response index.