Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic degenerative joint disorder caused by cartilage degradation and prolonged mechanical stress, resulting in structural alterations of the joint and surrounding tissues [1, 2]. Its pathology includes cartilage loss, osteophyte formation, joint space narrowing, and synovial inflammation, while clinically it presents as chronic joint pain and discomfort [1, 3]. From 1990 to 2019, OA prevalence increased by 48%, affecting approximately 350 million individuals globally [4], with the knee being the most frequently affected joint [5]. OA has a complex etiology involving aging, joint injury, sex, biomechanical stress, and genetic factors [1, 6]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified over 100 genetic variants significantly associated with OA [7]. As no cure exists, most patients rely on long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, while those intolerant to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may receive intra-articular treatments such as corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, platelet-rich plasma, or mesenchymal stem cell therapy. In advanced stages, joint replacement is often required [8]. These interventions, however, may lead to adverse effects and impose a substantial economic burden, with treatment costs accounting for 1–2.5% of the gross national product in some countries [9, 10]. Identifying additional OA risk factors is therefore essential for improving prevention and management strategies [11].

Physical activity (PA) is associated with numerous health benefits, including improved skeletal muscle density and reduced risks of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, lipid disorders, and various cancers [12]. PA helps mitigate age-related physiological decline through several mechanisms. It enhances muscle strength and mass, optimizes joint load distribution, increases basal metabolic rate and bone density, reduces body fat and cardiovascular risk factors, and improves endothelial, cognitive, and mental functions [13]. Recent studies suggest that moderate PA may help prevent OA and relieve its symptoms, whereas excessive long-term PA may increase OA risk [14–16]. However, the observational nature of these studies limits causal inference due to potential confounding factors such as sex, age, environment, and sampling bias [17]. Thus, building on previous findings, further investigation is needed to clarify the causal relationship between PA and OA [14–16].

Mendelian randomization (MR) is a method based on Mendelian genetics that enables the assessment of causal relationships between exposures and outcomes using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as instrumental variables (IVs) [18, 19]. By minimizing confounding and avoiding reverse causality due to the unidirectional nature of genetic variation, MR can overcome key limitations of observational studies [20]. This approach has been widely applied to explore causal relationships in various contexts [21–23]. Although observational studies suggest that moderate PA may help prevent OA, while excessive PA may increase its risk, the causal nature of this association remains uncertain. To address this, we investigated the genetic causal relationship between three types of PA – moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA), vigorous physical activity (VPA), and strenuous sports or other exercises (SSOE) – and knee osteoarthritis (KOA). This study aimed to provide genetic-level evidence to clarify the PA-KOA relationship, offering insights that may inform prevention strategies and exercise-based interventions for OA.

Material and methods

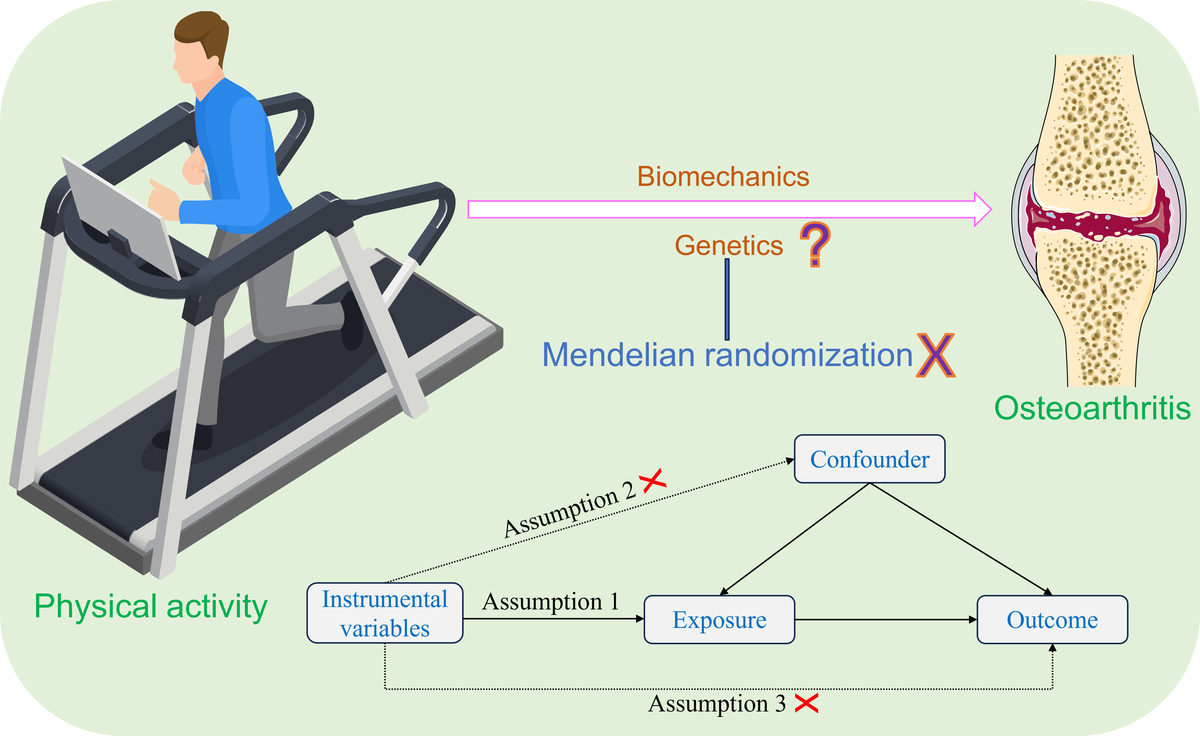

Study design

In this study, PA – including MVPA, VPA, and SSOE – was used as the exposure, and KOA as the outcome. A two-sample MR analysis was performed to assess the genetic causal relationship between PA and KOA. To satisfy the core assumptions of MR, IVs must be strongly associated with the exposure, independent of confounders and the outcome, and influence the outcome exclusively through the exposure pathway. All datasets used were publicly available, and thus no ethical approval or informed consent was required. Detailed dataset information is provided in Supplementary Table SI. A visual overview of the study design is presented in Figure 1.

GWAS summary data for PA and KOA

The GWAS summary data for PA, including MVPA, VPA, and SSOE, were retrieved from the IEU Open GWAS database (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/), generated by the UK Biobank. The GWAS summary data for MVPA consisted of 377,234 samples and 11,808,007 SNPs. Similarly, the GWAS summary data for VPA and SSOE consisted of 261,055 samples and 11,803,978 SNPs, and 350,492 samples and 11,807,536 SNPs, respectively. More detailed information about the data can be found in published studies [24]. The GWAS summary data for KOA were obtained from the IEU Open GWAS database, which was generated by the Arthritis Research UK Osteoarthritis Genetics (arcOGEN) Consortium. The dataset included information from 11,655 participants, all of European ancestry, and 1,279,483 SNPs. Further details are available in published studies [25].

IV selection

To ensure the robustness and reliability of our MR analysis results, a rigorous selection process was performed to identify suitable IVs that met the three key assumptions of MR analysis. Firstly, we identified SNPs strongly associated with the exposures (MVPA, VPA, SSOE) with a significance threshold of p < 5 × 10–7, and F statistic > 10 [26, 27]. The F statistic was calculated using the formula: F = R2(N-K-1)/K(1-R2) [28, 29]. Secondly, to address the issue of strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) among the selected SNPs, a clumping process was carried out with a threshold of r2 < 0.001 and clumping distance of 10,000 kb [30]. Thirdly, SNPs associated with KOA with a significance threshold of p < 5 × 10–7 were excluded. Fourthly, potential confounding factors were identified using the PhenoScanner database [31]. We identified the main risk factors for OA, including aging, obesity and gender [32–34]. Finally, to ensure that the SNP effect alleles for the exposure matched those used for the outcome, palindromic SNPs with intermediate allele frequencies were excluded [35].

MR analysis

The R (version 4.1.2) TwoSampleMR and MRPRESSO packages were employed to conduct two-sample MR analyses of PA, including MVPA, VPA, and SSOE, and KOA. The random-effects inverse variance weighted (IVW) method was used as the primary analytical approach, while the weighted median, simple mode, and weighted mode were applied as supplementary methods. The random-effects IVW method predominated our MR analysis results. Finally, the maximum likelihood, penalized weighted median, and IVW (fixed effects) validation methods were used to further identify the genetic causal association between PA (MVPA, VPA, SSOE) and KOA.

Sensitivity analysis

The study applied various statistical methods to assess the validity and robustness of the genetic causal association between PA and KOA. Cochran’s Q statistic and Rucker’s Q statistic were employed to detect heterogeneity of MR analysis. The MR Egger intercept test was used to detect horizontal pleiotropy. Additionally, the MR pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO) method was used to detect horizontal pleiotropy and outlier SNPs, with the global test of MR-PRESSO detecting horizontal pleiotropy and the outlier test of MR-PRESSO detecting outliers. Leave-one-out analysis was performed to assess whether the genetic assessment results were influenced by a single SNP. The MR robust adjusted profile score (MR-RAPS) method was employed to validate the normal distribution of MR analysis. A p-value > 0.05 indicates the absence of heterogeneity or horizontal pleiotropy, as well as conformity to normal distribution and robustness of the results.

Results

IV selection

We identified 11, 4, and 17 SNPs strongly associated with MVPA, VPA, and SSOE, respectively, for use as IVs in the MR analysis of KOA. None of these SNPs showed associations with KOA or potential confounders. All selected SNPs had F statistics > 10, met the criteria for valid instrumental variables, and were non-palindromic (Supplementary Tables SII–SIV).

MR analysis

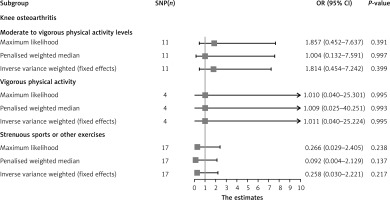

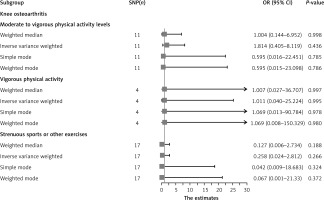

The results of the random-effects IVW analysis indicated that there was no significant genetic causal relationship between MVPA (p = 0.436, odds ratio [OR] = 1.814, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.405–8.119]), VPA (p = 0.995, OR = 1.011, 95% CI [0.040–25.224]), SSOE (p = 0.266, OR = 0.258, 95% CI [0.024–2.812]), and KOA. The findings from the weighted median, simple mode, and weighted mode analyses were consistent with those of the random-effects IVW analysis (p > 0.05) (Figures 2, 3). Finally, the maximum likelihood, penalized weighted median, and IVW (fixed effects) analyses indicated no genetic causal relationship between MVPA, VPA, and SSOE, and KOA (p > 0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 2

MR analysis results of PA (MVPA, VPA, SSOE) and KOA. Four methods: random-effects IVW, weighted median, simple mode, and weighted mode

Sensitivity analysis

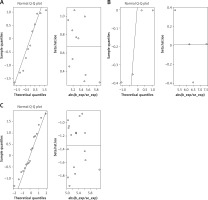

Cochran’s Q statistic of MR-IVW revealed no heterogeneity in the MR analysis of MVPA (p = 0.304), VPA (p = 0.963), SSOE (p = 0.234), and KOA. Similarly, Rucker’s Q statistic of MR Egger indicated no heterogeneity in the MR analysis of MVPA (p = 0.304), VPA (p = 0.927), SSOE (p = 0.280), and KOA. The intercept test of MR Egger demonstrated no horizontal pleiotropy in the MR analysis of MVPA (p = 0.595), VPA (p = 0.753), SSOE (p = 0.211), and KOA. Additionally, the global test of MR-PRESSO analysis showed no horizontal pleiotropy in the MR analysis of MVPA (p = 0.302), VPA (p = 0.968), SSOE (p = 0.229), and KOA. The outlier test of MR-PRESSO analysis revealed no outliers in the MR analysis of MVPA, VPA, and SSOE, and KOA (Table I). Furthermore, the leave-one-out analysis demonstrated that the MR analysis results of MVPA, VPA, and SSOE, and KOA were not driven by a single SNP (Figure 5). Additionally, the MR-RAPS analysis showed that the MR analysis between MVPA, VPA, and SSOE, and KOA were normally distributed (p > 0.05) (Table I, Figure 6). However, no P-value was given for the MR-RAPS analysis of VPA and KOA because only four IVs were available, and MR-RAPS requires seven or more IVs to provide a p-value.

Table I

Sensitivity analysis of the MR analysis results of exposures and outcome

Discussion

This study comprehensively evaluated the potential genetic causal relationship between PA and KOA using MR analysis. By utilizing genetic variants as IVs, we sought to determine whether PA exerts a direct influence on KOA risk through inherited genetic pathways. Our findings reveal no evidence of a genetic causal link between PA and KOA. This suggests that previously observed correlations may be attributable to residual confounding, reverse causality, or environmental and lifestyle factors unrelated to genetic predisposition. These results underscore the multifactorial nature of OA and the methodological challenges inherent in disentangling causality from correlation. Further research incorporating diverse populations, joint-specific analyses, and integrated approaches may be necessary to fully elucidate the complex interplay between PA and OA pathogenesis.

The relationship between PA and OA remains a subject of ongoing debate. Previous studies reported that excessive PA related to occupational activities may elevate OA risk [36]. Conversely, other evidence suggests a more nuanced picture. For example, a meta-analysis found no causal link between PA and knee joint damage [37], and studies on articular cartilage indicate that PA-induced changes are reversible, with the tissue adapting over time [38]. Moreover, a long-term clinical follow-up study reported no significant association between PA intensity or duration and the risk of KOA, aligning with the findings of the present study [39]. These inconsistencies may reflect the complex pathogenesis of OA, wherein structural abnormalities of the joint – whether congenital or acquired – play a critical role [40]. Notably, high-intensity PA may precipitate joint injuries, especially in professional athletes, among whom lower limb injuries are disproportionately prevalent [41, 42]. Such injuries can destabilize joint architecture and alter biomechanics, leading to abnormal mechanical stress, cartilage degeneration, and localized aseptic inflammation [43]. In individuals with genetically driven joint malformations, prolonged PA may exacerbate a cycle of cartilage injury, repair, and reinjury, ultimately contributing to early-onset OA symptoms [40, 43]. Therefore, the impact of PA on OA risk may depend heavily on underlying joint integrity, and whether similar mechanisms operate in structurally healthy joints remains uncertain.

Exercise therapy has demonstrated clinical benefits for certain patients with OA. Community-based observational studies have reported that regular walking may reduce the frequency of knee pain in individuals with OA [44]. Similarly, a randomized controlled trial involving 415 symptomatic OA patients found that PA significantly improved both pain and joint function in those with KOA [45]. These therapeutic effects may be attributed to several mechanisms: PA contributes to lowering body mass index (BMI), thereby reducing the mechanical burden of obesity on joint structures [46]; it enhances the strength of periarticular muscles and ligaments, promoting joint stability [47]; and it may serve as a psychological distraction from pain and discomfort during activity. Nonetheless, current evidence remains insufficient to support the hypothesis that PA can directly alter the underlying pathophysiological progression of OA. Rather, the therapeutic benefits of PA appear to be primarily symptomatic, focusing on the relief of pain and improvement of physical function in affected individuals [8, 48].

Abnormal joint structure and altered biomechanical loading are potential mediators through which PA may contribute to the development of OA. While clinical interventions involving PA have been shown to alleviate certain OA-related symptoms – such as by reducing BMI, enhancing periarticular muscle strength, and diverting attention from pain – these effects are symptomatic and do not establish a definitive causal link between PA and OA. Given the inherent limitations of observational studies, including susceptibility to confounding and reverse causation, robust methods are required to clarify this association. Therefore, to more accurately determine the potential causal relationship between PA and OA, we utilized GWAS summary statistics from independent population cohorts. This approach minimizes sample overlap and enables an investigation of the genetic causal pathways connecting PA and OA, offering insights beyond those obtainable through traditional observational analyses.

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the GWAS summary data utilized were derived exclusively from individuals of European ancestry. As a result, the findings may not be generalizable to other ethnic or racial populations, where genetic architectures and environmental exposures may differ significantly. Second, the analysis was confined to KOA, the most prevalent and clinically significant subtype of OA. Consequently, the results may not be extrapolated to OA affecting other anatomical sites, such as the hip, hand, or spine, which may involve distinct etiological pathways and genetic determinants. Future studies incorporating more diverse populations and multiple OA phenotypes are necessary to validate and extend the current findings.

In conclusion, the findings of our study do not support a genetic causal relationship between PA and OA. Rather, previously reported associations may be attributable to shared underlying joint structural abnormalities or the secondary effects of PA interventions – such as reductions in BMI, improvements in periarticular muscle strength, and psychological distraction from pain. Accordingly, engaging in appropriate levels of PA is unlikely to induce OA in individuals with structurally healthy joints. In clinical contexts, while PA may offer symptomatic benefits for OA patients, particularly in terms of pain relief and functional improvement, its impact on the underlying disease progression appears limited. Thus, PA should be considered a supportive rather than a disease-modifying therapy in the management of OA.