Introduction

Ischemic heart disease (IHD), also known as coronary artery disease, is primarily caused by coronary artery narrowing or obstruction due to atherosclerosis, leading to reduced myocardial blood supply [1]. Clinically, IHD manifests as angina, myocardial infarction, and heart failure, severely impairing patients’ quality of life and placing a substantial burden on healthcare systems. The 2021 Global Burden of Disease (GBD 2021) study reported that IHD remained the leading cause of death worldwide [2]. Although incidence and death rates have declined in most high-sociodemographic index (SDI) regions, the absolute number of cases continues to rise [3]. These trends highlight IHD as a persistent global public health challenge, with considerable disparities across regions and socioeconomic groups.

Several studies have examined the epidemiological trends and disease burden of IHD at global, regional, and national levels. Over the past three decades, the age-standardized death rate of IHD has declined in high-income countries [4]. However, in low-income and middle-income countries, IHD incidence and death rates remain high, largely due to limited healthcare resources and suboptimal management of hypertension and diabetes [5, 6]. These studies provide valuable epidemiological insights, a comprehensive analysis of the current burden, recent trends, and health inequalities of IHD based on GBD 2021 data remains lacking, particularly in comparative studies across different SDI regions.

Building on previous research, this study utilizes the latest GBD 2021 data to comprehensively assess the global burden of IHD from 1990 to 2021, with a particular focus on prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs across different SDI regions. Beyond descriptive reporting, we integrate age–period–cohort and decomposition analyses to disentangle the contributions of demographic and epidemiological drivers, evaluate cross-country health inequalities using SII and CI, and apply Bayesian age–period–cohort modeling to project future trends. The novelty of this study lies in integrating inequality metrics and predictive modeling within a single framework, enabling both retrospective assessment and forward-looking projections. By combining these approaches, this study not only refines current knowledge but also highlights persistent disparities and likely trajectories of IHD, thereby offering actionable evidence to guide prevention strategies, inform resource allocation, and reduce the global burden of disease.

Material and methods

Data source

Data for this study were derived from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021), which provides standardized estimates of 371 diseases and injuries across 204 countries and territories [2]. The GBD database integrates information from diverse sources, including civil registration, censuses, surveys, disease registries, and health service records, with established methods for data harmonization and adjustment [2, 7]. It employs sophisticated methodologies to address missing data and adjust for confounding factors. The study design and methodological details of the GBD research have been extensively documented in existing GBD literature [4]. This study analyzed the incidence, age-standardized incidence rate, deaths, age-standardized death rate, DALYs rate, and age-standardized DALYs rate of IHD at the global, regional, and national levels from 1990 to 2021. Rates are reported per 100,000 population and age-standardized using the 2021 global population [4, 8]. All data are publicly available and can be accessed at https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2021/sources free of charge. In the GBD database, IHD is classified as a Level 3 cause under cardiovascular diseases, which belong to the Level 2 category within non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Additionally, this study utilized the SDI, a composite measure of income, educational attainment, and fertility rates. The SDI categorizes countries and regions into five quintiles: low, low-middle, middle, high-middle, and high.

Ethical considerations

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the exemption for this study, as it utilized publicly available data that did not contain confidential or personally identifiable patient information.

Statistical analysis

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the IHD burden, a descriptive analysis was conducted at the global, regional, and national levels. Age-standardized measures of incidence, prevalence, deaths, and DALYs from 1990 to 2021 were summarized by sex and SDI quintiles, with comparative snapshots for 1990 and 2021. Analyzing temporal trends in disease burden is essential for understanding epidemiological patterns and informing public health strategies. This study examined global and SDI-regional IHD trends using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to calculate the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) and joinpoint regression to detect significant shifts in temporal patterns. To account for differences in age distribution, age-standardized rate (ASR) was calculated using the following formula:

where ai represents the specific rate in a given age group, wi denotes the corresponding population weight from the selected standard population, and A is the total number of age groups. The EAPC was derived from a log-linear regression model, Y = α + βX + ε, where Y represents ln(ASR), α is the intercept, x is the calendar year, ε is the error term, and β indicates the direction and magnitude of the trend. EAPC and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were computed as [9]: EAPC = 100 × [exp(β) – 1]. If the estimated EAPC and the lower bound of its 95% CI are both greater than 0, ASR is considered increasing. If the upper bound of the 95% CI is below 0, ASR is considered decreasing. Otherwise, ASR remains stable. Joinpoint regression further quantified annual percentage change (APC) and average annual percentage change (AAPC) [10, 11], identifying significant trend shifts using a log-linear model and Monte Carlo permutation test.Additionally, an age-period-cohort (APC) model incorporating the intrinsic estimator (IE) method was employed to disentangle the independent effects of age, period, and cohort on the IHD burden, thereby addressing the collinearity issue inherent in these variables and ensuring statistical validity [12]. In this study, age was grouped into 20 categories (< 5 years, 5–9 years … 90–94 years and ≥ 95 years), and periods were divided into 5-year intervals (1992–1996 … 2017–2021). APC modeling was performed using the NCI Age-Period-Cohort Tool [13], with Wald χ2 tests for statistical inference. A two-sided α = 0.05 was considered significant.

Decomposition analysis was applied to quantify the contributions of age structure, population growth, and epidemiological trends to changes in DALYs from 1990 to 2021. This study employed Das Gupta’s decomposition method, a mathematical approach that partitions overall changes into distinct components, enabling the quantification of each factor’s specific contribution. The number of DALYs for each location was calculated using the following formula:

To analyze cross-country health inequalities, this study followed the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations and employed the Slope Index of Inequality (SII) and the Concentration Index (CI) to assess absolute and relative income-related inequalities across countries and regions. SII, an absolute measure, reflects disparities between the most disadvantaged and most affluent groups, derived from regression of health outcomes against SDI ranking values. CI, a relative measure, ranges from –1 to 1, with values closer to 0 indicating lower inequality. A positive CI suggests better outcomes in higher-SDI regions, while a negative CI indicates the reverse. The CI was calculated as:

To support more effective public health policymaking and healthcare resource allocation, this study employs the Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort (BAPC) model to forecast the future burden of IHD. Built within the generalized linear model (GLM) framework under a Bayesian paradigm, the BAPC model enables the dynamic integration of age, period, and cohort effects. These effects are assumed to evolve over time and are smoothed using a second-order random walk, enhancing predictive accuracy through refined posterior probability estimates. The model further assumes that historical trends provide a reasonable basis for extrapolating future disease burden, while uncertainty is quantified through posterior distributions. To further improve computational efficiency and address the mixing and convergence challenges associated with traditional Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, the BAPC analysis incorporates the Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (INLA). This approach ensures robust and efficient inference while maintaining the model’s flexibility in handling time-series data. Given its adaptability to age-structured population data and its ability to capture complex cohort effects, the BAPC model is particularly well-suited for long-term disease burden projections. It should be noted, however, that the model assumes that historical trajectories will continue into the future, and that its reliability depends on data quality and appropriateness of prior specifications. In this study, the ‘BAPC’ R package was used, along with GBD 2021 data and population projections from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), to predict the global IHD burden over the next 10 years. To evaluate the robustness of the model, hindcasting experiments were also conducted.

Results

Descriptive analysis of IHD burden at global, SDI regional and national levels

Table I and Figure 1 present global, regional, and national estimates of IHD prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs. From 1990 to 2021, crude numbers of cases and deaths increased, whereas age-standardized indicators followed distinct trajectories. The ASPR remained essentially unchanged (EAPC = 0.00, 95% CI: –0.02 to 0.03), while ASIR, ASDR, and age-standardized DALY rates showed consistent declines (EAPCs: –0.44%, –1.30%, and –1.20%, respectively). The reductions were most pronounced in high-SDI regions, particularly in ASDR (EAPC –3.43%), whereas middle- and low-middle-SDI regions experienced modest increases in ASPR with largely stable DALY rates. In low-SDI regions, both ASIR and DALY rates declined slightly, although the magnitude of reduction was limited. Burden increased markedly with advancing age, especially among individuals aged ≥ 55 years, and remained consistently higher in males than females (Supplementary Figure S1). At the national level, Figure 1 highlights striking cross-country heterogeneity, with Gulf states and several small island nations exhibiting the highest age-standardized rates, in contrast to much lower levels observed in East Asian countries.

Table I

Numbers and age-standardized rates (ASR) of prevalence of prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs for ischemic heart disease in 1990 and 2021, along with the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) from 1990 to 2021

Trends in IHD burden using joinpoint regression analysis

Supplementary Table SI and Figure 2 present the joinpoint regression results for the burden of IHD. Overall, ASIR, ASDR, and age-standardized DALY rates declined significantly worldwide, while ASPR showed a slight upward trend. Periods of accelerated change were observed, with the steepest declines in ASIR (2005–2009), ASDR (2003–2006), and DALYs (1994–1998), whereas ASPR rose most sharply after 2015. Regional disparities were evident: high-SDI regions achieved the most sustained reductions, particularly in ASDR, while middle-SDI regions displayed fluctuating patterns and low-SDI regions showed only minimal declines. Low-middle SDI regions experienced temporary reversals in ASDR, especially around 1998–2001 and 2014–2021. Sex-stratified analyses revealed broadly similar trends, though males consistently carried a higher burden.

Age-period-cohort analysis on IHD DALYs

Supplementary Figure S2 presents the results of the age-period-cohort (APC) analysis for the age-standardized DALYs rate of IHD. The age effect revealed a steady increase in risk with advancing age, particularly after 80 years, while high-SDI regions consistently maintained lower levels across age groups. The period effect indicated a global decline, most pronounced in high- and high-middle-SDI regions, whereas low-middle SDI regions showed a relative increase. Cohort analysis demonstrated a gradual reduction in IHD burden across successive birth cohorts, supporting the role of improved interventions and living conditions over time.

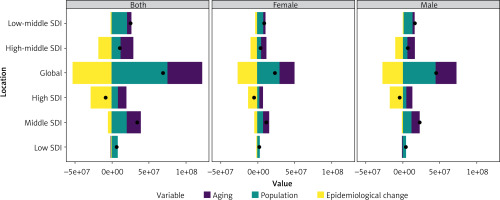

Decomposition analysis on IHD DALYs

Over the past three decades, global IHD DALYs increased markedly, with middle-SDI regions contributing to the largest rise (Figure 3). Decomposition analysis indicated that population growth accounted for over 100% of the increase globally (109.65%), while aging contributed 67.14%. In contrast, epidemiological changes offset much of this growth, reducing DALYs by 76.79%. Regional patterns varied: aging had the strongest impact in high-middle SDI regions (154.37%), population growth was most influential in low-SDI regions (123.10%), and epidemiological changes played a dominant role in high-SDI regions, where they reduced DALYs by more than threefold (–338.54%). Sex-stratified analyses showed that males consistently bore a higher DALY burden, although the relative contributions of demographic and epidemiological drivers differed across SDI levels.

Cross-country inequality analysis

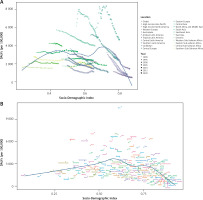

Over time, both relative and absolute inequalities in the burden of IHD across SDI regions have increased significantly (Figure 4). The Slope Index of Inequality (SII) declined from 2,888 (95% CI: 2,325–3,452) in 1990 to 1,388 (95% CI: 842–1,933) in 2021, and the Concentration Index (CI) decreased from 0.22 to 0.10. These reductions suggest modest progress in narrowing disparities, yet high-SDI populations continue to benefit disproportionately, indicating that global improvements have not been equitably shared.

Figure 4

SDI-related health inequality regression (A) and concentration curve (B) for global IHD disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 1990 and 2021

From 1990 to 2021, the relationship between IHD DALYs and SDI exhibited an inverted ‘W’ pattern: when SDI < 0.4, DALYs gradually increased; when 0.6 < SDI < 0.7, DALYs showed a fluctuating upward trend; when SDI > 0.7, DALYs declined sharply (Figure 5 A). Several regions, including North Africa and the Middle East, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, Central Europe, and Oceania, exhibited higher-than-expected DALY rates, suggesting that factors beyond SDI may contribute to their elevated burden.

Figure 5

Association between ischemic heart disease burden and the SDI. A – Relationship between DALYs due to ischemic heart disease and SDI across 22 GBD regions from 1990 to 2021. B – Relationship between DALYs due to ischemic heart disease and SDI across 204 GBD countries from 1990 to 2021

At the country level, the relationship between DALYs and SDI across 204 countries followed a pattern of gradual increase followed by a sharp decline (Figure 5 B). Notably, Nauru had significantly higher-than-expected DALYs, indicating an extreme deviation from the general trend, warranting further investigation into its unique socioeconomic and health system factors.

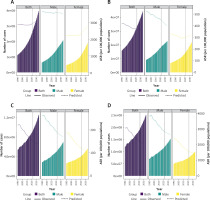

Predictive analysis on IHD burden to 2035

To project the future burden of IHD beyond 2021, this study employed the BAPC model to estimate the number of cases and ASRs from 2021 to 2035, stratified by sex (Figure 6). At the global level, the prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs of IHD are projected to increase continuously in absolute numbers. However, with the exception of prevalence, the ASRs for all other indicators are expected to decline over time, indicating an overall improvement in population-level health outcomes. Sex-stratified projections reveal distinct trends. Among males, the ASRs for all indicators are anticipated to decrease steadily. In contrast, among females, both the ASPR and ASIR are projected to increase. Specifically, the ASPR is expected to rise from 2,357.61 per 100,000 in 2021 to 2,789.17 per 100,000 in 2035, while the ASIR is projected to increase from 301.57 per 100,000 to 321.29 per 100,000 over the same period. Importantly, the BAPC model demonstrated adequate predictive performance in hindcasting deaths (Supplementary Figure S3), which supports the robustness of our projections. These findings underscore the potential for a shifting disease burden across sexes, warranting further investigation into sex-specific risk factors and healthcare strategies. It should be noted that BAPC projections rely on the assumption of smoothly evolving age, period, and cohort effects; as such, unexpected changes in risk exposures, interventions, or healthcare access may not be fully captured.

Discussion

Our analysis shows that the global burden of IHD has declined in age-standardized rates since 1990, largely due to improvements in high-SDI regions, yet absolute numbers of cases and deaths continue to rise because of population growth and aging. Marked inequalities persist across regions, and projections indicate further increases in absolute burden by 2035 despite continued declines in most standardized rates.

Although IHD still imposes an enormous global burden, age-standardized mortality and DALY rates have decreased since the early 2000s – mirroring better control of key risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, and diet, and improved access to statins and interventional care [1, 14]. Notably, joinpoint and APC studies on smoking-attributable IHD trends support the impact of tobacco control in accelerating these declines [15]. The sharpest reductions occurred in the early 21st century, coinciding with global initiatives on noncommunicable disease prevention. However, population aging, rising obesity, and diabetes prevalence now drive increasing prevalence rates [5], signaling that demographic and metabolic transitions may erode earlier gains.

Despite the overall downward trend in IHD burden, pronounced disparities persist across SDI regions, reflecting fundamental differences in healthcare capacity, policy implementation, and socioeconomic environments. Middle-SDI region recorded the highest absolute number of cases, whereas the low-middle SDI region exhibited the highest ASR. Over the past 30 years, certain indicators in middle-SDI, low-middle-SDI, and low-SDI regions have continued to rise, highlighting the need for further attention [16]. The persistence of high IHD burden in these regions is primarily driven by limited healthcare resources, inadequate chronic disease management systems, and insufficient health education [17], compounded by structural drivers such as rapid urbanization, population aging, and clustering of metabolic risks [18, 19]. In contrast, high-SDI countries experienced faster declines due to stronger health systems and early public health initiatives. Notable examples include the UK’s National Health Check Program (launched in 2004), Finland’s North Karelia Project (which successfully reduced national salt consumption), and comprehensive public smoking bans enforced in the UK, France, and Australia during the early 2000s [1, 20, 21]. By comparison, the rise of IHD in middle-SDI regions during the 1990s and 2000s was closely linked to industrialization, dietary transition, and urban lifestyles [22, 23]. In low-middle SDI regions, the ASDR increased during 1998–2001 and again in 2014–2021, potentially influenced by major socioeconomic crises such as the 1997–1998 Asian financial crisis and the 2019–2021 COVID-19 pandemic [24, 25]. These patterns illustrate that SDI does not only reflect economic development, but also the resilience of health systems in mitigating external shocks. Importantly, the decline in CI should not be interpreted as a genuine narrowing of disparities. CI captures relative rather than absolute inequality, meaning that regions with persistently high baseline burdens may still face large health gaps even when CI falls. Similar findings have been reported in studies on urban health inequities, where statistical convergence did not always translate into real improvements in outcomes [26]. Addressing these entrenched disparities requires region-specific strategies. High-SDI countries continue to invest in precision medicine, genetic screening, and public health promotion [27–29], while low-middle-SDI regions face persistent challenges such as high tobacco use [4] and exposure to environmental pollutants [23]. Ultimately, SDI-driven inequalities highlight that the gap in IHD burden is not only a matter of epidemiology, but of system capacity and policy prioritization. To reduce these disparities, high-SDI regions should focus on disseminating cost-effective innovations to lower-resource settings, while low-SDI regions need to expand primary care coverage, implement large-scale tobacco and obesity control programs, and strengthen community-based health education. International organizations, including WHO and the UN, can facilitate these efforts by promoting knowledge transfer and providing financial and technical support, ensuring more equitable access to IHD prevention and treatment worldwide.

While SDI gradients explain broad disparities, notable exceptions at the national level highlight that SDI alone cannot fully capture the heterogeneity of IHD burden. In Arab nations such as the United Arab Emirates and the Syrian Arab Republic, the IHD burden is particularly high, largely attributable to the high prevalence of obesity and diabetes [30]. In contrast, Japan and South Korea experience a significantly lower IHD burden, largely due to their lower obesity rates, widespread early screening programs, and effective weight management strategies [31, 32]. These contrasts illustrate how proactive prevention and early detection can offset demographic and lifestyle risks. However, Nauru presents a striking exception with DALYs far exceeding expectations due to extreme obesity (90% overweight, 71% BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and severely limited healthcare capacity [33].

In comparison, Peru – despite having a similar socioeconomic profile – reports far lower IHD burden, reflecting the protective role of healthier dietary habits, broader healthcare accessibility, and stronger chronic disease management. Similarly, evidence from Catalonia indicates that residents originating from higher-risk European countries face elevated coronary heart disease risk, underscoring the need for tailored prevention, early screening, and adequate resource allocation even within low-risk settings [34]. Effective IHD prevention requires not only resource allocation along SDI gradients but also context-specific strategies tailored to national health risks and systems. Examples such as Japan’s systematic screening, South Korea’s nationwide weight management programs, and Peru’s emphasis on dietary interventions demonstrate how country-specific best practices can mitigate inequality and provide replicable models for other settings.

Age, period, and cohort (APC) effects provide important context for IHD dynamics, with details presented in the appendix. Briefly, our results confirm that IHD risk increases markedly with age, especially after 80 years, highlighting the urgent need for targeted prevention and management in the elderly. Building on this age effect, our sex-stratified analysis reveals a consistent excess burden among males compared to females, aligning with prior evidence [35–37]. This gender disparity can be explained by a combination of biological mechanisms, metabolic and behavioral risk factors, and social determinants. Estrogen exerts a cardioprotective effect in females through multiple mechanisms. It activates the PI3K/Akt pathway, which inhibits oxidative stress and apoptosis, while simultaneously enhancing nitric oxide (NO) synthesis. This leads to improved vascular relaxation and a slower progression of atherosclerosis [38]. By contrast, men exhibit higher metabolic risks – such as elevated LDL-C, insulin resistance, and central obesity [1] – and are more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors including smoking, excessive alcohol intake, and physical inactivity. Future interventions should adopt sex- and age-sensitive strategies. For men, priorities include targeted health education, smoking and alcohol cessation, and promotion of regular physical activity, while for women, strengthening awareness of cardiovascular risks after menopause and improving early screening uptake are crucial. In elderly populations, individualized management and comprehensive geriatric care should be emphasized to address the rapidly rising burden in those aged ≥ 80 years.

Notably, although the ASRs of incidence, deaths, and DALYs for IHD are projected to decline annually by 2035, the absolute number of cases is expected to increase. This divergence reflects the dominant role of demographic shifts, as decomposition analysis shows that population growth and aging have been the main drivers of rising IHD DALYs over the past three decades and are expected to remain key contributors in the future [39]. According to UN estimates, the global population will approach 9.7 billion by 2050, with the proportion of individuals aged ≥ 60 years doubling between 2015 and 2050. These demographic transitions, compounded by the increasing prevalence of obesity and other chronic conditions, suggest that the global IHD burden will remain substantial. Targeted prevention and management strategies are therefore essential, particularly for older adults and high-risk groups. At the population level, strategies should aim to enhance health system preparedness for demographic transitions. Expanding primary care capacity, integrating chronic disease management into community health services, and implementing large-scale obesity and dietary risk reduction programs will be critical. Moreover, policy-level measures – such as taxation on unhealthy foods, subsidies for healthier diets, and urban planning that promotes physical activity – can help mitigate the long-term impact of population growth and aging on IHD burden.

This study has several notable strengths. It adds to the growing body of research by systematically examining cross-national inequalities in the burden of IHD from 1990 to 2021. By highlighting regional disparities, this study provides useful evidence to inform global health strategies aimed at optimizing healthcare delivery, improving resource allocation, and reducing health inequities. In addition, the study employs a comprehensive analytical framework – including descriptive, trend, decomposition, inequality, and predictive analyses – which helps generate a multidimensional understanding of the IHD burden. A particular novelty of this work lies in the integration of inequality metrics and predictive modeling within a single framework, enabling both retrospective assessment of disparities and forward-looking projections of future trends. Furthermore, it leverages the latest Global Burden of Disease 2021 dataset, which incorporates a globally diverse sample and advanced statistical methods, thereby enhancing the reliability and generalizability of the findings. However, this study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged. First, due to disparities in healthcare infrastructure and system capacity, the GBD dataset may underestimate case numbers in less developed countries. These limitations stem from inadequate disease surveillance systems and a shortage of healthcare professionals, potentially leading to misdiagnosis, underreporting, and other data quality issues [40, 41]. Second, the GBD estimation methodology relies on multiple assumptions and modeling techniques, which may introduce uncertainties and systematic biases. Third, while the Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort (BAPC) model provides valuable projections, its predictive accuracy depends on assumptions of temporal continuity and stable risk factor trends. This means the model may not fully account for unforeseen events – such as pandemics, economic crises, or major policy shifts – that could alter disease trajectories. As such, the projections should be interpreted with caution and regarded as indicative rather than definitive. Lastly, the feasibility of conducting inequality analyses for Australia and tropical Latin America is limited, as the GBD dataset includes only two countries from these regions, restricting the robustness of regional comparisons.

In conclusion, although the ASR of IHD has declined, the absolute burden remains high, with pronounced disparities across SDI regions and countries. Lower-SDI regions continue to bear a disproportionate burden, largely driven by demographic and metabolic shifts. These findings highlight the urgent need for region-specific prevention and management strategies, complemented by strengthened international collaboration to reduce global health inequities.