Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases, primarily atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), remain the leading cause of mortality worldwide and account for approximately 38% of deaths in Poland [1]. Dyslipidemia is a major risk factor contributing to ASCVD [2]. Elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is found in nearly 60% of the Polish population, yet only 16% of patients after acute myocardial infarction (MI) achieve the recommended LDL-C level of < 55 mg/dl [3]. National cardiovascular care programs and dedicated guidelines have been implemented in Poland to improve evidence-based ASCVD management and to overcome the burden of lipid disorders associated with both LDL-C and a newly established cardiovascular risk factor, lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] [4, 5].

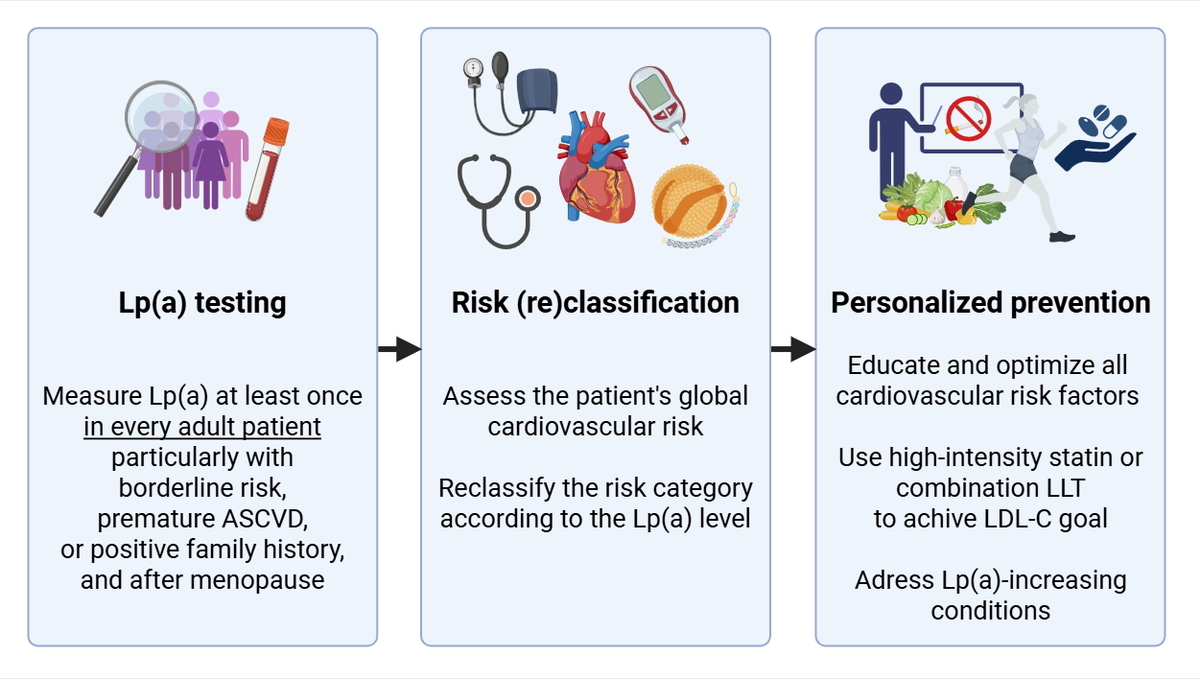

Lp(a) consists of an apolipoprotein B-containing LDL-like particle covalently bound to apolipoprotein(a) [apo(a)] (Figure 1) [6]. The latter is composed of a genetically determined number of kringle-IV (KIV) domains, which accounts for apo(a) size variation and inversely correlates with Lp(a) levels [7]. Up to 90% of the Lp(a) concentration can be explained by genetic variants in the LPA locus [8]. On a per-particle basis, Lp(a) is approximately six times more atherogenic than LDL [9]. In addition, it acts as a principal carrier of plasma oxidized phospholipids, which exert a proinflammatory effect [10]. Epidemiological and Mendelian randomization studies demonstrated a causal, continuous, and independent association between increased Lp(a), ASCVD, and aortic valve stenosis (AS) [11].

Figure 1

Structure of lipoprotein(A). Created with BioRender.com

Apo – apolipoprotein, CE – cholesterol esters, Chol – cholesterol, KIV-2 – kringle IV domain type 2, LDL – low-density lipoprotein, oxPL – oxidized phospholipids, TG – triglycerides.

Elevated Lp(a) is estimated to affect about 1.5 billion people worldwide, including 6 million in Poland [12]. Lifestyle measures and currently available treatments only mildly influence Lp(a) levels [13], while novel therapies showed a potential to reduce Lp(a) by up to 98% [14]. Awaiting the results of the phase III clinical outcome trials, Lp(a) measurements have been advocated to identify patients at increased cardiovascular risk [15]. Lp(a) testing and management have been covered by several guidelines and consensus statements [16], including the most recent 2025 Focused Update of the 2019 Guidelines for the management of dyslipidemias of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) [17]. Despite convincing evidence, the world testing rate is estimated at only 1–2%, with considerable variability between countries [18].

Aiming to facilitate the incorporation of Lp(a) into routine patient care in Poland, in this clinically oriented review, we discuss (i) up-to-date evidence on the role of Lp(a) in cardiovascular diseases, (ii) recent real-world data on the characteristics of the Polish patients affected by elevated Lp(a), and (iii) strategies for Lp(a) testing and management in light of the latest European and Polish guidelines.

Lipoprotein(a) testing for cardiovascular risk stratification

According to the updated ESC/EAS Guidelines, Lp(a) measurement should be considered at least once in the lifetime of every adult [17]. However, the Polish Cardiac Society and the Polish Lipid Association, alongside the American National Lipid Association, explicitly recommended it [19, 20]. Lp(a) measurement should be considered as early as possible to prevent premature events, ideally as part of the initial lipid profile [18, 19]. Hormonal changes, chronic comorbidities, acute conditions, or pharmacological interventions might trigger intra-individual Lp(a) variability, raising the need for repeated Lp(a) measurement [21, 22]. Statistically significant Lp(a) fluctuations were reported in primary prevention patients as well as those enrolled in cardiac rehabilitation, yet their clinical relevance remains uncertain [23, 24]. Populations that may particularly benefit from Lp(a) testing are listed in Table I.

Table I

Cardiovascular risk increases linearly by 11% for each 50 nmol/l higher Lp(a) [25]. Relative to the Lp(a) concentration of 7 mg/dl, Lp(a) levels of 30, 50, 75, 100, and 150 mg/dl result in 1.2-, 1.4-, 1.7-, 1.9-, and 2.7-fold higher risk for major adverse cardiac events (MACE), respectively [16]. While Lp(a) between 30 and 50 mg/dl belongs to the grey zone, Lp(a) of 50 mg/dl is associated with clinically relevant cardiovascular risk, and Lp(a) of 180 mg/dl poses a risk for MI equivalent to genetically diagnosed familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) [26, 27]. As per updated ESC/EAS Guidelines, Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl constitutes a risk-enhancing factor and should be considered beyond the SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP algorithms [17]. In clinical practice, an online calculator can be used to demonstrate how a given Lp(a) level alters the patient’s baseline risk for MI and stroke up to the age of 80 years [28].

Given the continuous relationship between Lp(a) and ASCVD, Lp(a) thresholds should not be solely used to determine the individual cardiovascular risk, but rather to exclude risk enhancement [15, 18]. Lp(a) thresholds introduced by national and international societies are presented in Table II [15–20, 29–32]. Alarmingly, the joint threshold of 50 mg/dl is inconsistently converted into either 105 nmol/l or 125 nmol/l, whereas reporting in molar units is preferred due to apo(a) size variability [33, 34]. Among 126,936 subjects from the Danish general population, Lp(a) ≥ 105 nmol/l was associated with increased risk for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 1.16 and 1.05, respectively) [35]. Therefore, it seems reasonable to consider Lp(a) levels from the range 105–125 nmol/l as risk-enhancing, as well as those > 125 nmol/l. In clinical practice, Lp(a) levels can be reported in mass units, whereby the clear threshold of 50 mg/dl should be followed, and imprecise unit conversion should be avoided [17, 19].

Table II

Lipoprotein(a) thresholds

| Society | Lp(a) level | Classification |

|---|---|---|

| AHA/ACC (2018) [29] | ≥ 50 mg/dl (≥ 125 nmol/l) | Risk-enhancing factor |

| HEART UK (2019) [30] | 32–90 nmol/l | Minor risk |

| 90–200 nmol/l | Moderate risk | |

| 200–400 nmol/l | High risk | |

| > 400 nmol/l | Very high risk | |

| CCS (2021) [31] | ≥ 50 mg/dl (≥ 100 nmol/l) | Risk modifier |

| EAS (2022) [15] | < 30 mg/dl (< 75 nmol/l) | No risk |

| 30–50 mg/dl (75–125 nmol/l) | Grey zone | |

| > 50 nmol/l (> 125 nmol/l) | At risk | |

| HAS (2023) [32] | ≥ 50 mg/dl (≥ 125 nmol/l) | Risk modifier |

| PCS/PoLA (2024) [19] | < 30 mg/dl (< 75 nmol/l) | Low risk |

| 30–50 mg/dl (75–125 nmol/l) | Moderate risk | |

| > 50–180 mg/dl (> 125–450 nmol/l) | High risk | |

| > 180 nmol/l (> 450 nmol/l) | Very high risk | |

| NLA (2024) [20] | < 30 mg/dl (< 75 nmol/l) | Low risk |

| 30–50 mg/dl (75–125 nmol/l) | Moderate risk | |

| ≥ 50 mg/dl (≥ 125 nmol/l) | High risk | |

| ESC/EAS (2025) [17] | ≥ 50 mg/dl (≥ 105 nmol/l) | Risk modifier |

| Lp(a) International Task Force (2025) [18] | ≥ 50 mg/dl (≥ 105 nmol/l) | Increased risk |

[i] ACC – American College of Cardiology, AHA – American Heart Association, CCS – Canadian Cardiovascular Society, EAS – European Atherosclerosis Society, HAS – Hellenic Atherosclerosis Society, ESC – European Society of Cardiology, NLA – National Lipid Association, PCS – Polish Cardiac Society, PoLA – Polish Lipid Association, UK – United Kingdom.

Consistency in Lp(a) reporting and interpretation is lacking due to technical difficulties with Lp(a) measurement. First, test results may be affected by unbound apo(a), which however represents a negligible proportion, ≤ 5%, of total apo(a) [36]. Second, calibration differences lead to significant inter-assay variability, precluding the transition between assays once Lp(a) is re-measured, and limiting the reliability of the results close to clinically relevant thresholds [34]. A recent study reported low biological Lp(a) variability among elderly individuals, suggesting that the major changes in Lp(a) levels described in the literature may be of technical nature [37]. Third, commercially available assays apply anti-apo(a) polyclonal antibodies that recognize epitopes on the repeated KIV-2 domains [38]. Lp(a) levels may thus be over- or underestimated in samples with large or small apo(a) isoforms, respectively [34, 36–38]. Nevertheless, a novel isoform-independent assay, which measures intact Lp(a) particles exclusively, was introduced to overcome these limitations [39].

Heritability of elevated lipoprotein(a)

Up to 90% of Lp(a) heritability is attributable to the LPA gene encoding apo(a) [40]. Although the number of KIV-2 repeats has the strongest impact on Lp(a) levels, this inverse relationship is complex [41]. First, the two LPA alleles in heterozygotes are not equally expressed, as maturation and secretion of smaller apo(a) isoforms are more efficient [41]. Second, the LPA expression is modified by single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are differently distributed across populations and occur within the specific apo(a) isoform size ranges [41].

Most SNPs reduce Lp(a), e.g. through loss-of-function mutations, and concordantly affect cardiovascular risk [40–43]. Elevated Lp(a) is found in 47% and 32% of first- and second-degree relatives of individuals with Lp(a) ≥ 125 nmol/l, respectively [44]. At a median follow-up of 19 years, first-degree relatives of individuals with elevated Lp(a) had an increased risk of MACE (HR = 1.08, HR = 1.30, and HR = 1.28 for index Lp(a) levels at the 50–80th, 80–95th, and ≥ 95th percentile, respectively, compared to the < 50th percentile) [45]. In simplified terms, this complex autosomal co-dominant inheritance ultimately results in about 50% risk of Lp(a) elevation if one parent has significantly elevated Lp(a). Therefore, cascade screening is crucial to identify individuals at increased cardiovascular risk.

Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease

The impact of Lp(a) on the risk of cardiovascular diseases is summarized in Figure 2. The causal role of Lp(a) in ASCVD was first determined in genetic studies, as high Lp(a) levels along with corresponding genotypes were found to be strongly associated with coronary artery disease (CAD) and MI [46, 47]. Lp(a), unlike LDL-C, is predictive of the development of high-risk, vulnerable coronary plaques [48]. Among patients with advanced CAD, elevated Lp(a) accelerated the progression of low-attenuation plaques during 1-year observation (10.5% increase for each 50 mg/dl higher Lp(a)) [49]. Elevated Lp(a) increased the 8-year risk of MI in patients with stable chest pain suspected of CAD (HR = 1.91, p < 0.001), particularly in those with low-attenuation plaque, which mediated 73.3% of this relationship (HR = 3.03, p < 0.001) [50].

Figure 2

Lipoprotein(A) and cardiovascular diseases. Adapted from [27]. Adjusted hazard ratios for selected top vs. lower Lp(A) percentiles. Created with BioRender.com

HR – hazard ratio, Lp(A) – lipoprotein(A).

Lp(a) may contribute to vascular inflammation, as those with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dl had a higher fat attenuation index around the right coronary artery compared to the remaining forty patients receiving optimal lipid-lowering therapy (LLT) with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dl [51]. At 10-year follow-up, elevated Lp(a) correlated with pericoronary adipose tissue inflammation and plaque burden (0.32% increment in percent atheroma volume for each Lp(a) doubling) [52]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis including 30,073 individuals showed a positive association between Lp(a) and coronary artery calcium [53]. Among asymptomatic patients without established ASCVD, the risk of coronary calcification increased by 1% for each 1 mg/dl higher Lp(a) [54]. A meta-analysis of four cohort studies showed 58% higher risk for coronary calcification in asymptomatic ASCVD patients with Lp(a) in the top vs. bottom tertile [55].

The latest findings of the STAR-Lp(a) Study suggested that Lp(a) acts as a modifier of ongoing atherosclerotic processes rather than its initiator. First, an association between Lp(a) and atherosclerosis progression was found only in high-risk patients with elevated Lp(a), particularly in those with Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl, but not in healthy individuals with isolated Lp(a) elevation [56]. Coronary calcium score (339.9 vs. 43.1, p < 0.001), glycated hemoglobin (5.86% vs. 5.44%, p < 0.001), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP, 2.35 mg/l vs. 2.12 mg/l, p = 0.007) were higher in patients vs. the healthy group, indicating that the proatherogenic effect of Lp(a) is enhanced by metabolic disorders and inflammation [56]. Second, Lp(a) only weakly correlated with coronary artery calcification among 528 primary prevention patients, demonstrating statistical significance only in elderly individuals aged ≥ 65 years, who had a longer lifetime exposure to high Lp(a) and traditional cardiovascular risk factors [57].

The risk-enhancing effect of Lp(a) is independent of other biomarkers. Lp(a) was associated with cardiovascular risk regardless of hs-CRP levels in large primary and secondary prevention cohorts [58]. In a meta-analysis including 27,658 individuals, Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl was associated with increased cardiovascular risk regardless of achieved LDL-C level or absolute LDL-C change on statin treatment [59]. The highest risk estimate (HR = 1.90) was reported in those with Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl and LDL-C level at the 4th quartile, showing an independent and additive value of both biomarkers [59]. The Women’s Health Study confirmed that simultaneous measurement of Lp(a), LDL-C, and hs-CRP enables the most extensive risk stratification for MACE at 30 years [60].

As recently demonstrated among 207,368 primary prevention patients, measurement of both Lp(a) levels and apoB particle count most accurately reflects lipid-related cardiovascular risk [61]. Lipoprotein type or size did not significantly affect the risk for CAD, while Lp(a) added an independent prognostic value (area under the curve 0.774 vs. 0.769, p < 0.001) [61]. In a large primary prevention cohort, the risk for a composite endpoint increased by 24% for 100 nmol/l higher Lp(a) compared to only 5% for 100 nmol/l higher non-Lp(a) apoB-containing particles [62]. Although Lp(a) significantly contributes to the progression of ASCVD, it accounts for only a small proportion of the total apoB count. Therefore, other apoB-containing particles, with LDL-C as a proxy, remain the primary target of LLT [62].

Considering other clinical entities, genetically determined high Lp(a) contributes to aortic valve calcification and stenosis [63, 64]. In a meta-analysis comprising 710 patients with AS, the progression of peak aortic jet velocity and mean transvalvular gradient was accelerated by 41% and 57%, respectively, in those at the top compared to the bottom Lp(a) tertile [65]. Absolute risk driven by elevated Lp(a) seems the most pronounced for MI and AS [66]. Nonetheless, a causal relationship was also found between increased Lp(a), peripheral artery disease (PAD), and major adverse leg events (HR = 2.99 and rate ratio = 3.04, respectively) [67]. Moreover, large meta-analyses reported a significant association between elevated Lp(a) and ischemic stroke (standardized mean differences 0.76), as well as stroke recurrence and poor functional outcomes (odds ratio [OR] = 1.69 and OR = 2.09, respectively) [68, 69].

The role of Lp(a) in some cardiovascular diseases is not fully understood. An assumed association between Lp(a) and venous thromboembolism was not confirmed [70]. Conversely, a recent meta-analysis supported a causal relationship between Lp(a) and heart failure (HF) (OR = 1.064, p < 0.001) [71]. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether Lp(a) directly affects myocardial function or predisposes to HF secondary to CAD. In another meta-analysis of five Mendelian randomization studies, high Lp(a) was associated with atrial fibrillation (AF) (OR = 1.024, p < 0.001) [72]. However, available evidence is inconclusive, as other data suggested that elevated Lp(a) is mainly present in AF patients experiencing thromboembolic events [73]. Finally, very low Lp(a) appears to predispose to type 2 diabetes [74]. An increased risk for type 2 diabetes in loss-of-function homozygotes and subjects with genetically imputed Lp(a) < 3.5 nmol/l suggested a causal link, but the interplay between genetic factors, insulin dynamics, and metabolism requires further exploration [75].

Lipoprotein(a) in the Polish population

Elevated Lp(a) in the Polish population has been the subject of ongoing research. Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl was detected in 17.8% of 800 individuals aged 44 to 53 years [76]. After adjustment for age, Lp(a) was associated with female sex and LDL-C. The former likely reflects the Lp(a) increase observed in the perimenopausal period. Indeed, women aged > 52 years had higher Lp(a) compared to younger women (10.1 vs. 7.0 mg/dl, p = 0.034) [76]. Corresponding results were obtained in the STAR-Lp(a) Study [77]. The prevalence of Lp(a) ≥ 30 mg/dl and ≥ 50 mg/dl was 21.5% and 13.5%, respectively. Among 2,475 patients with a median age of 66 years, those with Lp(a) ≥ 30 mg/dl were more likely to be female (73% vs. 68.7%, p = 0.06) and more frequently suffered from comorbid hyperlipidemia (24.2% vs. 17.6%, p < 0.001) and AF (3.9% vs. 2.3%, p = 0.05). In addition, hypothyroidism, which increases Lp(a) levels, was more common in individuals with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dl vs. < 50 mg/dl [77]. Another analysis comprising 2,979 STAR-Lp(a) participants demonstrated higher Lp(a) in those with hypertension (9.6 mg/dl vs. 8.0 mg/dl, p < 0.001) and CAD (11.2 mg/dl vs. 8.7 mg/dl, p < 0.001), whereas no significant differences were found in those with a history of stroke [78].

Similar findings were presented in a recent study including 562 patients hospitalized at a tertiary center [79]. The prevalence of Lp(a) > 30 mg/dl reached 20.8%, while male sex was associated with lower Lp(a) (OR = 0.29, p = 0.0055). Individuals with elevated Lp(a) more often had a history of coronary artery bypass grafting (2.6% vs. 0.2%, p = 0.03) and tended to present with CAD (17.1% vs. 10.3%, p = 0.052) and AF (17.9% vs. 11.2%, p = 0.06) more frequently than those with Lp(a) < 30 mg/dl. In addition, peak aortic valve velocity of ≥ 1.8 m/s was more common in subjects with Lp(a) > 30 mg/dl. However, no correlation between Lp(a) and LDL-C was found. In contrast, analysis of 220 hyperlipidemic patients with a mean age of 49.1 years, including 36.8% with FH, reported a higher prevalence of elevated Lp(a) compared to the general population [80]. Lp(a) > 30 mg/dl and > 50 mg/dl were present in 38.3% and 28.3% of the study participants, respectively. After adjustment for sex and age, Lp(a) was higher in those with CAD (59 mg/dl vs. 37 mg/dl, p = 0.02), but not in those with carotid plaques or other cardiovascular diseases [80].

Greater Lp(a) prevalence was reported in the Zabrze-Lp(a) Registry, including 2,001 high-risk patients with a mean age of 66.4 years [81]. The median Lp(a) concentration was 6.6 mg/dl, while Lp(a) > 30 mg/dl, > 50 mg/dl, and > 75 mg/dl was found in 27%, 20%, and 2.9% of the study participants, respectively. No association between Lp(a) and sex was reported, but women constituted a relatively small proportion of the study population (37.1%). Patients with Lp(a) > 30 mg/dl were significantly older (68.3 years vs. 66.3 years, p = 0.04). The prevalence of Lp(a) > 30 mg/dl was particularly high among subjects with chronic coronary syndrome (52.2% vs. 41.5%, p < 0.001), those undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (23.9% vs. 19%, p = 0.01), and in those with a history of MI (20.6% vs. 14.9%, p = 0.0022). Individuals with Lp(a) > 30 mg/dl had lower hemoglobin (13.27 g/dl vs. 13.60 g/dl, p = 0.0006) and a higher platelet count (213.00 × 109/l vs. 204.63 × 109/l), N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (11.9 pg/ml vs. 9.44 pg/ml, p = 0.04), and CRP (16.1 mg/dl vs. 9.9 mg/dl, p = 0.01), but LDL-C did not differ significantly [81].

In line with the Zabrze-Lp(a) Registry, the Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital Research Institute Registry found Lp(a) > 30 mg/dl and > 50 mg/dl in 27.8% and 19.8% of 511 patients at the mean age of 48.2 years, respectively [82]. Lp(a) was higher in patients with a history of MI (51.47 mg/dl vs. 28.09 mg/dl, p < 0.001), but no difference was found between those with premature and non-premature MI. FH (24.24% vs. 13.05%, p = 0.005) and MI (17.82% vs. 7.33%, p < 0.001) were more common in subjects with Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl vs. < 50 mg/dl, with a similar trend observed for the threshold of 30 mg/dl. Additionally, when the cohort was divided into Lp(a) > 30 mg/dl and < 30 mg/dl groups, thyroid diseases, which differently affect Lp(a) levels, were found to occur more frequently in the former (26.76% vs. 18.14%, p = 0.033) [82]. Interestingly, a sub-analysis of 59 HF patients revealed a weak positive correlation between Lp(a) and CAD, but also identified high Lp(a) category as a significant predictor of HF (OR = 2.00, p = 0.009) [83].

Management of elevated lipoprotein(a)

Therapies targeting high Lp(a) are not available yet [84]. Statins may lead to mild, clinically irrelevant Lp(a) elevations, while ezetimibe and bempedoic acid have a neutral effect [85]. Conversely, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) modulators reduce Lp(a) by 20% to 30%. Alirocumab, evolocumab, and inclisiran are accessible for very high-risk patients in the Polish B101 drug program, yet only for LDL-C-lowering purposes [86]. Therefore, the current management of elevated Lp(a) is focused on optimization of other modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia, through lifestyle and drug interventions [15, 17, 19, 20]. Lp(a) measurement might hence allow for personalized ASCVD prevention and treatment [87].

Intensive LLT provides LDL-C reduction that may mitigate the increased cardiovascular risk attributable to high Lp(a) [15]. The ESC/EAS strongly encouraged high-intensity statins in patients with elevated Lp(a) [17]. According to Polish and American experts, ezetimibe and/or PCSK9 modulator should be considered on top of maximally tolerated statin in high- and very high-risk subjects with Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl, depending on the LDL-C goal [19, 20]. In addition, a combination of a lower-dose statin and ezetimibe may be considered as an alternative to statin monotherapy [19]. Among statins, pitavastatin may be considered, given its potential to slightly reduce Lp(a) [88]. Finally, lipoprotein apheresis should be considered in patients with Lp(a) ≥ 60 mg/dl facing ASCVD progression despite optimal control of all other cardiovascular risk factors [19]. Although primary prevention patients with Lp(a) > 50 mg/dl or genetic variants increasing Lp(a) levels might benefit from aspirin, the randomized evidence is insufficient, and the current guidelines do not mention Lp(a) elevation as an indication for aspirin use [89, 90].

Five Lp(a)-lowering drugs are currently in the advanced phase of clinical development, as summarized in Table III [91]. Pelacarsen, an antisense oligonucleotide, inhibits apo(a) synthesis by triggering degradation of apo(a) mRNA in the nucleus of hepatocytes [92–94], whereas olpasiran [95–98], lepodisiran [99, 100], and zerlasiran [101], small-interfering ribonucleic acids, target cytoplasmatic apo(a) mRNA. Unlike other injectable drug candidates, muvalaplin, similarly to new drug candidates, is an oral small molecule that prevents apo(a) from binding to apoB [102–105]. The observed Lp(a) reductions by 80–98% seems promising, as a 50 mg/dl decrease may translate into 20% lower risk for MACE at 5 years in secondary prevention settings [106]. Lp(a)-lowering agents not only robustly lower Lp(a) concentration but also diminish its pro-inflammatory oxidized phospholipid content [92, 93]. Additional modest reductions in LDL-C and hs-CRP might potentially help avoid polypharmacy [101, 102]. Nonetheless, whether Lp(a)-lowering effect improves clinical outcomes remains to be determined.

Table III

Lipoprotein(a)-lowering agents in development. Data from the phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials presented as the largest placebo-adjusted mean percent change in lipoprotein(a) level from baseline with the corresponding variation in the concentrations of other molecules

| Trial | Population | Lp(a) reduction | Other effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelacarsen IONIS-APO(a)-LRx, AKCEA-APO(a)-LRx, TQJ230 | |||

| Phase 2 NCT02160899 [92] | Lp(a) 50–175 nmol/l (cohort A) ≥ 175 nmol/l (cohort B) Healthy participants N = 64 | –62.8% (A) –67.7% (B) at day 85/99 with 100, 200, and 300 mg weekly for 4 weeks each | LDL-C (A/B): –13.0%/–23.9% apoB (A/B): –11.3%/–18.5% oxPL–apo(a) (A/B): –26.6%/–36.7% oxPL–apoB (A/B): –35.2%/–42.5% |

| Phase 2 NCT03070782 [93] | Lp(a) ≥ 60 nmol/l Established ASCVD N = 286 | –80%a at 6 months with 20 mg weekly | oxPL-apo(a): –70%a oxPL-apoB: –88%a |

| Lp(a)HORIZON Phase 3 NCT04023552 [94] | Lp(a) ≥ 70 mg/dl Established ASCVD N = 8,323 | Ongoing Completion: February 2026 | |

| Olpasiran AMG890 | |||

| OCEAN(a)-DOSE Phase 2 NCT04270760 [95, 96] | Lp(a) > 150 nmol/l Established ASCVD N = 281 | –101.1% at 36 weeks with 225 mg every 12 weeks | LDL-C: –23.1% apoB: –17.6% oxPL-apoB: –92.3% hsCRP: no effect |

| OCEAN(a)-Outcomes trial Phase 3 NCT05581303 [97] | Lp(a) ≥ 200 nmol/l MI and/or PCI with ≥ 1 risk factor N = 7,297 | Ongoing Completion: December 2026 | |

| OCEAN(a)-PreEvent Phase 3 NCT07136012 [98] | Lp(a) ≥ 200 nmol/l Age ≥ 50 years Established ASCVD or many risk factors N = 11,000 | Recruiting Completion: March 2031 | |

| Lepodisiran LY3819469 | |||

| ALPACA Phase 2 NCT05565742 [99] | Lp(a) ≥ 175 nmol/l Age ≥ 40 years Optimal LLT N = 320 | –96.8 p.p. at 240 days with 400 mg at day 0 and 180 | apoB: –15.5 p.p. |

| ACCLAIM-Lp(a) Phase 3 NCT06292013 [100] | Lp(a) ≥ 175 nmol/l Established ASCVD or > 55 years with high ASCVD risk N = 16,700 | Recruiting Completion: March 2029 | |

| Zerlasiran SLN360 | |||

| ALPACAR-360 Phase 2 NCT05537571 [101] | Lp(a) ≥ 125 nmol/l Established ASCVD N = 178 | –85.6%b at 36 weeks with 450 mg every 24 weeks | LDL-C: –25.1%b apoB: –15.0%b |

| Phase 3 | No phase 3 trial | ||

| Muvalaplin LY3473329 | |||

| KRAKEN Phase 2 NCT05563246 [102] | Lp(a) ≥ 175 nmol/l Age ≥ 40 years ASCVD or FH or DM2 N = 233 | –85.8% at 12 weeks with 240 mg daily | apoB: –16.1% hsCRP: –6.1% |

| MOVE-Lp(a) Phase 3 NCT07157774 [103] | Lp(a) ≥ 175 nmol/l Established ASCVD N = 10,450 | Recruiting Completion: March 2031 | |

| AZD4954 Oral small molecule | |||

| Phase 1 NCT06980428 [104] | Lp(a) ≥ 30 mg/dl Healthy participants N = 120 | Recruiting Completion: December 2026 | |

| YS2302018 Oral small molecule in pre-clinical development [105] | |||

b time-averaged, apo – apolipoprotein, ASCVD – atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, DM2 – type 2 diabetes mellitus, FH – familial hypercholesterolemia, hsCRP – high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, LDL-C – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LLT – lipid-lowering therapy, Lp(a) – lipoprotein(a), MI – myocardial infarction, oxPL – oxidized phospholipids, PCI – percutaneous coronary intervention.

Conclusions and future perspectives

High Lp(a) is causally associated with a broad spectrum of cardiovascular diseases, comprising AS, CAD, MI, HF, PAD, and stroke. The independent character of this relationship supports a multimarker approach to cardiovascular risk stratification, with Lp(a) being assessed alongside other lipid (LDL-C, apoB), inflammatory (hsCRP), and metabolic (HbA1c) parameters. The correlation between Lp(a), AF, and type 2 diabetes remains unclear. The latter requires investigation in the context of emerging Lp(a)-lowering therapies.

The prevalence of elevated Lp(a) in the Polish population is approximately 20%, but appears higher among individuals at increased cardiovascular risk. Higher Lp(a) may be found in postmenopausal women, emphasizing the need to close the gender gap in ASCVD management [107]. Patients with elevated Lp(a) are likely to display other risk factors, such as advanced age or hyperlipidemia, that cumulatively enhance ASCVD progression, and therefore should be identified and addressed according to the current guidelines.

Lp(a) concentration should be assessed at least once in every individual. The thresholds of 30 mg/dl and 50 mg/dl allow for practical reclassification of cardiovascular risk. The Lp(a) testing rate in Polish hospitals has increased approximately five-fold in the last 7 years, yet remains insufficient, particularly among high-risk patients, indicating the need for education of medical professionals [108]. The availability of Lp(a) tests in Poland is improving, with the national primary care program “Moje Zdrowie” (“My Health”) offering Lp(a) screening to individuals aged > 20 years since May 2025 [109].

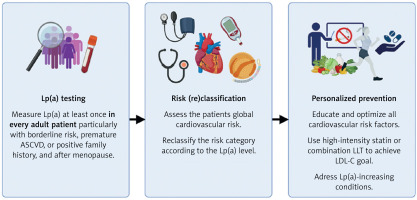

Lp(a) measurements in the primary prevention settings are not only clinically valuable, but also highly cost-effective, with the potential to save PLN 314 per person in Poland [110]. To ensure benefits for both patients and the healthcare system, Lp(a) testing must be followed by personalized optimization of all modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, as shown in Figure 3. The results of the Lp(a)HORIZON and OCEAN(a) Outcomes trials are expected in 2026–2027. Until then, early, intensive, and patient-tailored LLT remains the cornerstone of ASCVD prevention and treatment in individuals with elevated Lp(a).

Figure 3

Lipoprotein(A) testing and management in clinical practice. Created with BioRender.com

ASCVD – atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, LDL-C – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LLT – lipid-lowering therapy, Lp(A) – lipoprotein(A).